Despite Challenges, Ending Early Marriage in Ethiopia Is Possible

(April 2011) Ethiopia has one of the highest rates of early marriage in the world, with one in two girls marrying before her 18th birthday and one in five girls marrying before the age of 15.1 However, prevalence rates vary greatly by region and are often higher than national figures, such as in the Amhara region in northern Ethiopia, where almost 50 percent of girls are married by age 15 (see Figure 1).2 Although the Ethiopian constitution explicitly states that “marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses” and the minimum legal age for marriage is 18 for both boys and girls, the laws are not always enforced.3 Early marriage remains a deeply rooted tradition in Ethiopian communities, perpetuated by poverty, a lack of education and economic opportunities, and social customs that limit the rights of women and girls.

Figure 1

Age at First Marriage or Union for 20-to-24-Year-Old Females by Region

Note: Figures are based on the 2005 Demographic Health Survey in which women ages 20–24 reported being married by age 18 and age 15.

Sources: Population Council and UNFPA, The Adolescent Experience In-Depth: Using Data to Identify and Reach the Most Vulnerable Young People: Ethiopia 2005 (New York: Population Council, 2009).

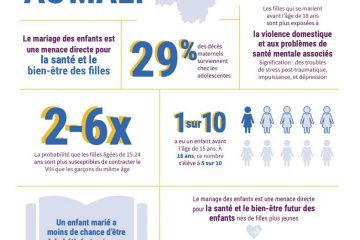

Harmful Consequences of Early Marriage

The consequences of early marriage are physically, emotionally, and socially devastating. An analysis of several indicators from the 2005 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) in Ethiopia (the most recent DHS) shows that marital status greatly influences the sexual experiences and reproductive health of girls and young women in Ethiopia.4 Married girls are significantly more likely than their unmarried peers to be sexually active (73 percent versus 0.3 percent) and because of tremendous social pressure for them to prove their fertility, these young brides become young mothers with the attendant dangers of early childbearing. In addition, only 21 percent of ever-married 15-to-24-year-old females (including those who were separated, divorced, or widowed) reported ever using a modern method of contraception.5 With limited autonomy to make decisions and influence sexual relations, married girls face a greater risk of gender-based violence and marital rape. Moreover, young mothers are especially vulnerable to poor reproductive health outcomes, including prolonged and obstructed labor, obstetric fistula, and death.6

Early marriage also heightens the social and economic insecurity of girls, women, and families. In Ethiopia, girls who are married before age 15 are more likely to be illiterate and are less likely to be enrolled in school (see Figure 2). In 2005, only 12 percent of ever-married 15-to-19-year-old females were enrolled in school compared to 60 percent of 15-to-19-year-old females who were not married and did not have a child.7

Figure 2

Percent of 15-to-24-Year-Old Females Who Are Illiterate, by Marital Status

Note: Figures are based on the 2005 Demographic Health Survey in which women ages 20–24 reported being married by age 18 and age 15.

Sources: Population Council and UNFPA, The Adolescent Experience In-Depth: Using Data to Identify and Reach the Most Vulnerable Young People: Ethiopia 2005 (New York: Population Council, 2009).

Efforts to Change the Practice

Clearly, girls and young women in Ethiopia face quite a challenge; however, a number of nongovernmental and community organizations are working to change attitudes about early marriage and create an environment where girls can thrive. The Berhane Hewan program (“Light for Eve” in Amharic), carried out by the Population Council, is one of the few child marriage prevention interventions that has been rigorously evaluated. The program, which targeted married and unmarried girls ages 10 to 19 in rural Ethiopia, resulted in increases in girls’ social networks, age at marriage, reproductive health knowledge, and contraceptive use between 2004 and 2006. Girls in the program site demonstrated improved knowledge of HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and family planning methods and were more likely to report having friends in the neighborhood. For example, girls who participated in the program were 1.8 times more likely to have used any family planning method compared with a control group.Young adolescents (ages 10 to 14) who participated in the program were 90 percent less likely to be married and three times more likely to be in school.8 By providing a package of interventions at both the community and individual level, the Berhane Hewan program was able to improve the social, educational, and health status of adolescent girls in Ethiopia.

Meanwhile, the 2007 Early Marriage Evaluation Survey (EMES) in Amhara region illustrates the importance of targeting families and communities with multiple messages about early marriage to foster social change. The study found that communities that had greater exposure to early marriage prevention messages (six messages or more) were more likely to report a higher cutoff age for marriage. Caretakers who were not exposed to any messages about early marriage considered marriage to be too early if it occurred before age 14.5. However, caretakers who were exposed to four to six messages considered a girl’s marriage to be too early if it occurred before age 15.8. Exposure to 10 or more messages increased the reported age to 17.9

At the same time, a higher level of exposure to prevention messages increased the percentage of community members who knew the minimum age at marriage or stopped a forced marriage. For instance, the percentage of caretakers who knew that the legal minimum age of marriage was 18 increased dramatically—from 8 percent among those not exposed to any messages to 34 percent among those who had seen or heard four to six messages.10

Others have recognized the importance of collaborating with influential local partners to change attitudes and behaviors. Under a large community-based reproductive health and family planning project, Pathfinder International/Ethiopia partnered with local NGOs, women’s associations, the ministries of Women’s Affairs and Justice, legal and civil society organizations, and schools to raise awareness about early marriage in Ethiopia at national, regional, and community levels. For example, Ye Ethiopia Goji Lemadawi Dirgitoch Aswegaj Mahber (EGLDAM, formerly known as the National Committee on Traditional Practices) and the Ethiopian Women Lawyers Association conducted advocacy workshops with district-level judicial bodies and law enforcement agencies as well as with religious leaders from Orthodox Christian, Muslim, Catholic, and Protestant faiths. These workshops educated community members about the legal rights of girls and mobilized support among influential leaders to end early marriage. Through these advocacy efforts, Pathfinder and its partners successfully prevented or annulled over 14,000 early marriages in the Amhara and Tigray regions between 2005 and 2006.11 Ultimately, by strengthening the capacity of judges, the police, and parliamentarians to enforce laws about the legal age of marriage for girls and educating stakeholders about the consequences of early marriage and childbearing, communities worked together to stop this harmful traditional practice.

Data collection for a new 2010-11 Ethiopia DHS is now being completed by ICF Macro and Ethiopia’s Central Statistical Agency. Although there was an obvious increase in the median age at marriage among women ages 25 to 49 between 1990 and 2000, there was little change observed between 2000 and 2005.12 The 2010-11 DHS should provide important new information on trends in age at first marriage throughout the country. With these new data, decisionmakers at all levels will be better positioned to support effective policies and programs aimed at improving the status and well-being of Ethiopian girls and women.

Alexandra Hervish is a policy analyst, International Programs, at the Population Reference Bureau.

References

- Central Statistical Agency (Ethiopia) and ORC Macro, Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005 (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Agency and ORC Macro, 2006).

- Annabel S. Erulkar and Eunice Muthengi, “Evaluation of Berhane Hewan: A Program to Delay Child Marriage in Rural Ethiopia,” International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 35, no. 1 (2009), accessed at www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/3500609.pdf, on Dec. 8, 2010; and Population Council and UNFPA, The Adolescent Experience In-Depth: Using Data to Identify and Reach the Most Vulnerable Young People: Ethiopia 2005 (New York: Population Council, 2009).

- USAID, “Child Marriage: Education and Law Deter Early Marriages in Ethiopia” (2008), accessed at www.usaid.gov, on April 11, 2011; and Pathfinder International, “Women’s and Girls’ Empowerment: Preventing Early Marriage” (2006), accessed at www.pathfinder.org, on April 7, 2011.

- UNFPA and Population Council, The Adolescent Experience In-Depth.

- UNFPA and Population Council, The Adolescent Experience In-Depth.

- Population Council, Child Marriage Briefing Ethiopia (New York: Population Council, 2004).

- Margot M. Kane, Ethiopia: Creating Partnerships to Prevent Early Marriage in the Amhara Region (Watertown, MA: Pathfinder International, 2006).

- Erulkar and Muthengi, “Evaluation of Berhane Hewan.”

- Anastasia J. Gage, Coverage and Effects of Child Marriage Prevention Activities in Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Findings From a 2007 Study (Washington, DC: USAID, 2009).

- Gage, Coverage and Effects of Child Marriage Prevention Activities in Amhara Region, Ethiopia.

- Kane, Ethiopia: Creating Partnerships to Prevent Early Marriage in the Amhara Region.

- Central Statistical Agency (Ethiopia) and ORC Macro, Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005 (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Agency and ORC Macro, 2006).