Overview of Quality of Care in Reproductive Health: Definitions and Measurements of Quality

Product: New Perspectives on Quality Care, no. 1

Author: PRB

Date: July 1, 2002

In this Series

Quality of care, a client-centered approach to providing high-quality health care as a basic human right, has emerged as a critical element of family planning and reproductive health programs. It has been promoted by local stakeholders, such as women’s health and primary health care organizations, and affirmed at international conferences, such as the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development.

High-quality services ensure that clients receive the care that they deserve. Furthermore, providing better services at reasonable prices attracts more clients, increases the use of family planning methods, and reduces the number of unintended pregnancies. Several impact studies have shown that improving the quality of reproductive health services increases contraceptive use. Studies in Bangladesh, Senegal, and Tanzania showed that women’s contraceptive use was higher in areas where clients felt that they were receiving good care than it was in areas with lower-quality health facilities (Koenig et al. 1997; Mroz et al. 1999; Speizer and Bollen 2000).

Providing high-quality care also makes sense for service providers, since improving basic standards of care attracts more clients, reducing per capita costs of services and ensuring sustainability. For example, the Bangladesh Women’s Health Coalition attracts clients by providing a mix of services, so that clients can use a visit for more than one purpose, and by having well-trained paramedical personnel, rather than physicians, perform pelvic exams, IUD insertions, and menstrual regulation services. The high volume of clients has enabled the program to distribute its fixed costs over a larger number of clients, allowing the coalition to serve more people at a lower cost (Kay et al. 1991, as cited in Kols and Sherman 1998).

Improving the quality of reproductive health care programs benefits other health services as well, in part by encouraging users to seek higher-quality services for all of their health care needs. In addition, improvements to health care facilities can enhance the quality of care for a wide range of adult and child health care needs.

This policy brief discusses the various definitions of quality of care in the context of reproductive health, and suggests tools for measuring it. The brief provides a framework for other policy briefs in the series, and uses definitions developed through the Maximizing Access and Quality (MAQ) Initiative. The U.S. Agency for International Development’s Office of Population and its partner agencies designed the MAQ Initiative to serve clients and programs by developing cost-effective ways to improve both access to and quality of reproductive health services. It is important to understand how the MAQ principles evolved, since various frameworks may be appropriate for different situations and practice settings.

Defining Quality of Care

While most people feel that improving quality of services is important, health specialists do not always agree about which components should be included in the definition of quality.

Historically, quality has been defined at a clinical level, and involves offering technically competent, effective, safe care that contributes to the client’s well-being. But quality of care is a multidimensional issue that may be defined and measured differently, according to stakeholders’ priorities.

- Clients, whose perception of quality may be influenced by social and cultural concerns, place significant emphasis on the human aspects of care (see Policy Brief 2, Client-Centered Quality: Clients’ Perspectives and Barriers to Receiving Care;

- Providers usually stress the need for technical competency, as well as infrastructure and logistical support from their institution (see Policy Brief 3, Providers and Quality of Care;

- Program managers may focus on support systems, such as logistics and recordkeeping; and

- Policymakers and donors are concerned with cost, efficiency, and outcomes for health investment as a whole.

The complexity of defining quality of care makes it difficult to identify and measure improvements in service delivery.

The Basic Definition of Quality of Care: The Bruce-Jain Framework

The Bruce-Jain framework, developed in 1990, is often considered the central paradigm for quality in international family planning. Judith Bruce and Anrudh Jain, researchers for the Population Council, have defined quality as “the way individuals and clients are treated by the system providing services” (Bruce 1990; Jain 1989). The framework identifies six elements, which apply mainly to clinical services, relevant to improving the quality of care in family planning programs: choice of contraceptive methods, information given to patients, technical competence, interpersonal relationships, continuity and follow-up, and the appropriate constellation of services.

Expanding the Scope of Quality of Care

Since the development of the Bruce-Jain framework, health care specialists have suggested several changes to broaden or modify the definition of quality of care, including the following options:

- Extending the framework to other aspects of reproductive health services, such as prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STIs); provision of maternal health services, including post-abortion care; and screening, counseling, and referral services for victims of violence (Mora et al. 1993);

- Paying more attention to the health structures that can improve quality of care, such as follow-up and continuity mechanisms (AbouZahr et al. 1996);

- Addressing incentives and disincentives in family planning, such as providing food or money to women who undergo sterilization (Hardon et al. 2001);

- Considering gender relations, both in the population served and between providers and clients (AbouZahr et al. 1996);

- Adding formal standards for quality of care, such as treatment protocols and clinical practice guidelines developed by ministries of health, professional organizations, or the facility itself (Brown et al. 2000); and

- Considering clients’ access to family planning and reproductive health services, including the distance clients must travel to reach services, the costs of services, the attitudes of providers, and unnecessary eligibility requirements that exclude clients based on age, marital status, or gender (Bertrand et al. 1995).

All of these modifications supplement the basic Bruce-Jain framework, placing the client at the center of the concept of quality of care, while also emphasizing the importance of technical standards and of increasing access to information and services. These elements apply to community-based as well as clinical services.

The Client’s Rights

The Client and Provider Bill of Rights, created by the International Planned Parenthood Foundation (IPPF), outlines 10 rights of family planning clients, and extends the definition of a client to everyone in the community who needs services, not merely those who approach the system (Huezo and Díaz 1993). According to the IPPF, the client’s perspective of the quality of care emphasizes method choice and availability, respectful and friendly treatment, privacy and confidentiality, service providers’ professional competence, information and counseling, convenient hours and acceptable waiting times, and affordability. Three elements can help clients feel well-treated: face-to-face communication; skillful providers who show clients that they care about their work; and consideration of how women’s needs, fears, and reactions may be perceived differently by male and female providers (Díaz 1994).

The IPPF’s bill of rights also addresses 10 needs of providers, including training and updated technical guidance; adequate supplies and strong infrastructure; and feedback and support from clients, other providers, managers, and supervisors.

Gender

The IPPF/Western Hemisphere Region (IPPF/WHR) further refines the definition of quality of care by considering the gender aspects of relationships between clients and providers. Gender refers to the roles, attitudes, values, and relationships affecting women and men throughout the world. The IPPF, in conjunction with three regional family planning associations and the Latin American and Caribbean Women’s Health Network, has developed a manual for evaluating quality of care from a gender perspective, with an eye toward improving gender equity and sexual rights; assessing how well gender concepts have been incorporated into the institution; and strengthening staff members’ ability to analyze how well they have integrated gender concepts into their delivery of reproductive health services.

The IPPF/WHR methodology, which has been tested in Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Peru, indicates that while senior management and staff are generally committed to resolving gender and reproductive health issues, more work needs to be done to provide gender-sensitive services, such as counseling for women who have experienced gender-based violence, and to develop gender-supportive institutions, including antidiscrimination policies (IPPF/WHR 2000).

Improved Program Standards

The Quality Assurance Project (QAP), a U.S. consortium led by the University Research Corporation’s Center for Human Services, describes quality as a comprehensive and multifaceted concept that measures how well clients’ expectations, as well as providers’ technical standards, are met. QAP’s tools and methods, which are based on quality management principles derived from industry, are applied to the accreditation of facilities, supervision of health workers, and other efforts to improve health workers’ performance and the quality of health services in less developed countries (Reerink and Sauerborn 1995).

Quality in health care can be broken down to three mutually reinforcing components: quality design, quality control, and quality improvement.

- Quality design uses planning tools first to define an organization’s mission, including identifying its clients and services, and then to allocate resources and set standards for service delivery;

- Quality control applies monitoring, supervision, and evaluation methods to ensure that every employee meets the established standards and delivers high-quality services; and

- Quality improvement involves solving problems and improving processes (Kols and Sherman 1998).

Family planning and other health care programs in less developed countries began adopting various components of quality assurance nearly two decades ago. For instance, QAP used quality design concepts to develop the Latin American Maternal Mortality Initiative, a regional effort to strengthen the delivery of essential obstetric care at the health facility and community levels (Quality Assurance Project 2002).

Making Services and Information More Accessible

The MAQ initiative strives to improve access to and quality of family planning and reproductive health services for both clients and providers. Program managers and policymakers often consider access, which refers to how difficult it is for a client to obtain services, and quality simultaneously when deciding how best to strengthen service delivery. The MAQ concept considers the client’s perspective both before the client reaches the clinic and once the client is being treated (Shelton 2001).

The initiative has helped address clients’ and providers’ needs, both by identifying best practices to foster client-provider interaction and by developing or strengthening technical standards of quality. The standards improve providers’ ability to meet clients’ desires for accessible, safe, effective family planning and reproductive health services; information and education about their contraceptive choices; and privacy. At the same time, these standards enable providers to develop and update their skills, procure and manage supplies, and receive better supervision.

Measuring Quality of Care

Several approaches have been used to measure quality of care in family planning and reproductive health care programs. Measuring quality is important for several reasons: It signals what is important, monitors what is happening, and allows the appropriate parties to address what is happening.

Signaling What Matters

By measuring quality, observers can determine an intervention’s effectiveness, and can provide information for future program strategies. Furthermore, measuring quality demonstrates to providers that quality is a critical component of their work, and sets a standard for providers’ performance (MEASURE Evaluation 2001).

Monitoring the Situation

Tools for monitoring quality of care can be either quantitative or qualitative. Quantitative studies may have greater scientific rigor, but they may seem too remote to affect providers directly; qualitative studies help engage staff in improving programs, but may not be considered scientific enough to be creditable. Both types of evaluations have their place (Bertrand 2002).

Several quantitative approaches and tools have been used to monitor the effectiveness of reproductive and child health services.

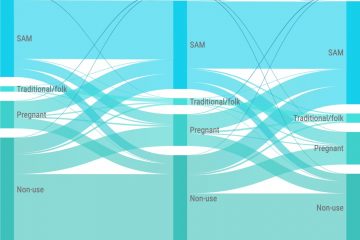

- The Service Availability Module (SAM), an optional addition to the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), was the first quantitative tool used to measure a population’s access to reproductive and child health services. The SAM collects information from community members about barriers to seeking care at clinics, then verifies whether the facilities offer certain basic services (such as immunizations and family planning services).

- Situation Analysis (SA), developed by the Population Council in 1989, created widespread awareness about the importance of facility-based surveys in evaluating the availability, functioning, and quality of family planning and reproductive health programs. SA studies conducted in nearly 40 countries have shown that services often fail to meet minimal standards of care.

- The Service Provision Assessment (SPA), a combination of the SAM and SA, covers family planning, safe motherhood, newborn care, child survival, and HIV/AIDS. The SPA survey is designed to be used by a local agency under the direction of a country’s health ministry; technical assistance is provided by ORC Macro International (MEASURE Evaluation 2002).

The Quick Investigation of Quality (QIQ), a subset of the SPA, was developed in 1999 by the MEASURE Evaluation project, in collaboration with the Monitoring and Evaluation Subcommittee of the MAQ Initiative. MAQ researchers use a list of 25 indicators to monitor quality of care in clinic-based family planning programs. MAQ considers these indicators, which have been culled from over 100 possible choices, the most important to achieving quality of care outcomes (see Box 1, below). The QIQ survey was developed to meet the needs of all stakeholders while remaining low-cost and easy to use. Data are measured using a variety of tools, including interviews with providers, observations of client-provider interactions (CPI), exit interviews with clients, and facility audits. QIQ recommends using all three of these instruments to obtain the most complete picture of a group of health facilities. These and other tools used in measuring quality from both the client’s and provider’s perspectives are listed in Box 2, below.

Managing the Situation

Using management techniques that emphasize quality of care can enable program staff, clients, and other stakeholders to identify and correct shortcomings in service delivery. They also benefit clients by providing improved services, and motivate clients to use services that can meet their reproductive health needs (MEASURE Evaluation 2001). Qualitative approaches and tools, such as Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI), Client-Oriented Provider-Efficient services (COPE), and Performance Improvement (PI), include data collection as well as quality improvement components (EngenderHealth 1995; Management Sciences for Health 1993).

- CQI, a management technique that encourages staff members from all levels to collaborate on analysis to continuously improve services (Calla 1991, as cited in Kols and Sherman 1998), helps institutionalize customer service practices. The Family Planning Service Expansion and Technical Support Project (SEATS II) and the American College of Nurse-Midwives relied on CQI to help the Zimbabwe Nurses Association, a group of private midwives, tackle barriers to providing reproductive health services on a fee-for-service basis, retain clients in the face of price increases, reduce waiting times, and develop referral guidelines (Family Planning Service Expansion and Technical Support/John Snow, Inc. 2000).

- The COPE approach, designed by EngenderHealth (formerly AVSC International) enables a facility’s providers, supervisors, and other staff to jointly assess services. COPE uses various tools (including self-assessment guides, client-interview protocols, client-flow analyses, and action plans) to help participants identify problems and develop effective solutions. Studies have shown increased quality of care resulting from the use of COPE techniques (see Policy Brief 3, Providers and Quality of Care). Training modules have also been adapted to cover other reproductive health topics, such as maternal care, infection prevention, postabortion care, and sterilization services (Wolff et al. 1996).

- Performance Improvement (PI), a process used in industry since the 1960s, has been used more recently by program staff, clients, and other stakeholders to identify and correct shortcomings in service delivery. Programs in over a dozen countries have used PI to respond to clients’ requests, strengthen supervision, develop a community-based distribution program, and improve private-sector client counseling (Lande 2002).

The use of these and other approaches is still in the preliminary phase, and continues to be studied. Future documentation of results will be useful for family planning and reproductive health services providers who are committed to quality improvements.

Improving Quality of Care: Next Steps

Improving quality of care for clients means understanding their cultural values, previous experiences, and perceptions of the role of the health system, and then bringing reproductive health service providers and the community together to map out a shared vision of quality. Similarly, enhancing quality of care for providers requires identifying their motivations, addressing their needs (including general administrative and logistical support from the health care system), and helping them to better understand and address clients’ concepts of quality. Ethnographic studies, situation analyses, and other research initiatives are being used to help identify and establish ways to measure quality from both clients’ and providers’ perspectives. More research is needed to identify and address the needs of clients who may need family planning and reproductive health services but who are not receiving care due to a variety of barriers. Similarly, additional research must be undertaken to determine whether initiatives to improve providers’ performance, such as training, the provision of job aids, self-assessment tools, enhanced supervision and ongoing evaluation, and improved infrastructure and facilities, actually affect client outcomes.

Conclusion

Creating a shared vision for improved quality of care requires that program managers, service providers, researchers, and consumer advocates commit to the idea that quality matters. Health specialists continue to refine how quality of care is defined and measured, even as women’s groups and nongovernmental organizations encourage clients and communities to expect and demand quality health care services. Increased efforts must be made to understand and motivate providers, improve their performance, and help make them partners in improving access to and quality of family planning and reproductive health care services. Given time and effort, the ongoing attempt to improve the quality of care will translate into services that both meet high quality standards and satisfy the needs of clients and providers around the world.

Liz C. Creel, Justine V. Sass, and Nancy V. Yinger of the Population Reference Bureau (PRB) prepared this brief in collaboration with Kristina Lantis, Cynthia P. Green, and Stephanie Joyce of the Population Council. PRB gratefully acknowledges the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) for supporting this project. This policy brief was funded through FRONTIERS and MEASURE Communication, through Cooperative Agreements Nos. HRN-A-00-98-00012-00 and HRN-A-00-98-000001-00, respectively. Special thanks are due to the following reviewers: Michal Avni, Sarah Harbison, James Shelton, and Kellie Stewart, of the USAID Bureau for Global Programs, Office of Population; Ian Askew, James Foreit, Anrudh Jain, Federico León, Saumya RamaRao, Laura Raney, and John Townsend, Population Council; Jane Bertrand, Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, Center for Communication Programs; Elaine Murphy, Program for Appropriate Technology in Health; Jan Kumar, EngenderHealth; and Abbas Bhuiya, International Center for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh. Managing Editor: Helena Mickle, PRB.

References

Carla AbouZahr et al., “Quality Health Care for Women: A Global Challenge,” Health Care for Women International 17 (1996): 449-67.

Jane T. Bertrand, personal communication, March 2002.

Jane T. Bertrand et al., “Access, Quality of Care, and Medical Barriers in Family Planning Programs,” International Family Planning Perspectives 21, no. 2 (1995): 64-9, 74.

Lori DiPrete Brown et al., “Quality Assurance of Health Care in Developing Countries,” Quality Assurance Methodology Refinement Series (Bethesda, MD: Quality Assurance Project, 2000).

Judith Bruce, “Fundamental Elements of Quality of Care: A Simple Framework,” Studies in Family Planning 21, no. 2 (1990): 61-91.

C.D. Calla, “Translating Concepts of Total Quality Management to Improve Quality of Health Care in Family Planning Service Delivery Programs in Developing Countries” (Population Technical Assistance Project, 1991). Quoted in Adrienne J. Kols and Jill E. Sherman, “Family Planning Programs: Improving Quality,” Population Reports 26, no. 3 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, Population Information Program, 1998).

Soledad Díaz, “Quality is Client-Oriented,” Planned Parenthood Challenges 2 (1994): 31-33.

EngenderHealth, COPE: Client-Oriented Provider-Efficient Services: A Process and Tools for Quality Improvement in Family Planning and Other Reproductive Health Services (New York: EngenderHealth, 1995).

Family Planning Service Expansion and Technical Support (SEATS II)/John Snow, Inc., Mainstreaming Quality Improvement in Family Planning and Reproductive Health Services Delivery: Context and Case Studies (Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development, 2000).

Anita Hardon et al., Monitoring Family Planning and Reproductive Rights (New York: Zed Books, 2001).

Carlos Huezo and Soledad Díaz, “Quality of Care in Family Planning: Clients’ Rights and Providers’ Needs,” Advances in Contraception 9, no. 2 (1993): 129-39.

Anrudh K. Jain, “Fertility Reduction and the Quality of Family Planning Services,” Studies in Family Planning 20, no. 1 (1989): 1-16.

International Planned Parenthood Federation, Western Hemisphere Region (IPPF/WHR), Manual to Evaluate Quality of Care From a Gender Perspective (New York: IPPF/WHR, 2000).

Bonnie J. Kay et al., “The Bangladesh Women’s Health Coalition,” Quality/Calidad/Qualité, no. 3 (New York: Population Council, 1991): 1-24. Quoted in Adrienne J. Kols and Jill E. Sherman, “Family Planning Programs: Improving Quality,” Population Reports 26, no. 3 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, Population Information Program, 1998).

Adrienne J. Kols and Jill E. Sherman, “Family Planning Programs: Improving Quality,” Population Reports 26, no. 3 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, Population Information Program, 1998).

Michael A. Koenig et al., “The Influence of Quality of Care Upon Contraceptive Use in Rural Bangladesh,” Studies in Family Planning 28, no. 4 (1997): 278-89.

Robert E. Lande, “Performance Improvement,” Population Reports, Series J, no. 52 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, Population Information Program, 2002).

Management Sciences for Health, “Using CQI to Strengthen Family Planning Programs,” The Manager 2, no. 1 (1993): 1, 20.

MEASURE Evaluation, “Quick Investigation of Quality (QIQ): A User’s Guide for Monitoring Quality of Care in Family Planning.” MEASURE Evaluation Manual Series, no. 2 (Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2001).

MEASURE Evaluation, “Service Provision Assessment: Abstract,” accessed online at www.cpc.unc.edu/measure/cmnht/t6_abstract.html, on April 29, 2002.

G. Mora et al., “Quality of Care in Women’s Reproductive Health: A Framework for Latin America and the Caribbean,” draft (Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization, 1993).

Thomas A. Mroz et al., “Quality, Accessibility, and Contraceptive Use in Rural Tanzania,” Demography 36, no. 1 (1999): 23-40.

I.H. Reerink and R. Sauerborn. “Quality of Primary Health Care in Developing Countries,” International Journal for Quality in Health Care 8, no. 2 (1996): 131-39.

Quality Assurance Project, “Overview of Quality Assurance in Latin America,” accessed online at www.qaproject.org/lac.html, on April 29, 2002.

James D. Shelton, “The Provider Perspective: Human After All,” International Family Planning Perspectives 27, no. 3 (2001): 152-61.

Ilene Speizer and Kenneth A. Bollen, “How Well Do Perceptions of Family Planning Service Quality Correspond to Objective Measures? Evidence From Tanzania,” Studies in Family Planning 31, no. 2 (2000): 163-77.

James A. Wolff et al., eds., The Family Planning Manager: Basic Skills and Tools for Managing Family Planning Programs (Bloomfield, CT: Management Sciences for Health, Kumarian Press, 1996).

For More Information

For more information on the United States Agency for International Development’s Maximizing Access and Quality (MAQ) Initiative, go to www.MAQweb.org or download Best Practices in Client-Provider Interactions in Reproductive Health Services: A Review of the Literature (PDF: 143KB).

Box 1

Recommended List of Quality of Care Indicators

Provider

- Demonstrates good counseling skills

- Assures client of confidentiality

- Asks client about reproductive intentions (asking whether the client wants more children, and when)

- Discusses with client which method he or she would prefer

- Mentions HIV/AIDS (initiates or responds)

- Discusses methods for preventing pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections

- Treats client with respect/courtesy

- Tailors key information to the client’s needs

- Gives accurate information on the method accepted (explaining its use, side effects, and possible complications)

- Gives instructions on when to return

- Follows infection control procedures outlined in guidelines

- Recognizes/identifies contraindications, consistent with guidelines

- Performs clinical procedures according to guidelines

Staff (Other Than Provider)

-

- Treats clients with dignity and respect

Client

- Participates actively in discussion and selection of method

- Receives his or her method of choice

- Believes the provider will keep his or her information confidential

Facility

- Has all (approved) contraceptive methods available; no stock-outs

- Has basic items needed for delivery of methods offered by the facility (including sterilizing equipment, gloves, blood pressure cuffs, specula, adequate lighting, water)

- Offers privacy for pelvic exams/IUD insertions

- Has mechanisms to make programmatic changes based on client feedback

- Has received a supervisory visit within a certain predetermined period

- Has adequate storage of contraceptives and medicines (away from water, heat, direct sunlight) on premises

- Follows state-of-the-art clinical guidelines

- Has acceptable waiting time

Source: MEASURE Evaluation, “Quick Investigation of Quality” (2001).

Tools to Measure Improvements in Quality

Improving Provider Knowledge and Skills

- Pre- and post-tests; follow-up “post-post-tests”

- Provider observations

- Provider surveys

- “Mystery clients”

- Reviews of records

Increasing Client Satisfaction

- Client exit interviews

- Household interviews

- Focus group discussions

- Service statistics

Improving Facilities’ Capability or Readiness to Provide Quality Services

- Facility audits or assessments

- Provider surveys/focus group discussions

- Mystery clients

- Reviews of records

- Client flow analyses

Understanding Why Clients Do Not Use Services

- Focus group discussions with potential users or dropouts

- Household interviews with potential users or dropouts

Source: Family Planning Service Expansion and Technical Support/John Snow, Inc., Mainstreaming Quality Improvement in Family Planning and Reproductive Health Services Delivery (2000).

">

">

">

">

">

">