Over the past two decades, China’s population has been aging rapidly. As a result of China’s “one-child” policy and low mortality, the proportion of elderly citizens will continue to grow very quickly, increasing the stress on an already troubled health care system.

The Division of Behavioral and Social Research at the

National Institute on Aging (NIA) supports research on the

health of China’s elderly population. This work has contributed

to understanding the characteristics of China’s oldest-old

(ages 80 and older) and the dilemmas in meeting their

health care needs. This newsletter reviews some recent

research—both NIA-sponsored and other research—that

explores these challenges.

Demographic Context

China adopted a one-child policy in 1979 in order to stem

population growth and ensure economic stability. This policy

prohibits couples from China’s ethnic majority from having

more than one child. The policy did slow population

growth, increasing access to vaccinations and to improved

disease care and treatment. But with fewer children and

improved living standards, the proportion of elderly in

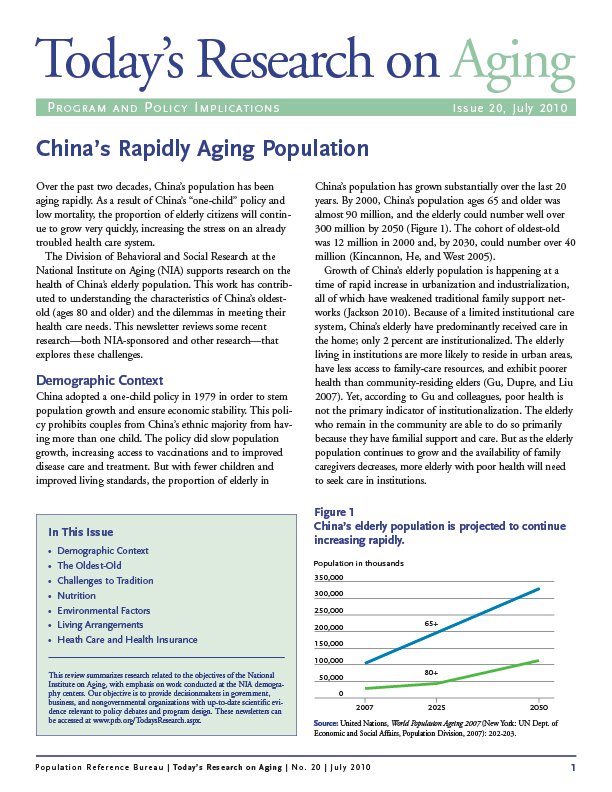

China’s population has grown substantially over the last 20

years. By 2000, China’s population ages 65 and older was

almost 90 million, and the elderly could number well over

300 million by 2050 (Figure 1). The cohort of oldest-old

was 12 million in 2000 and, by 2030, could number over 40

million (Kincannon, He, and West 2005).

Growth of China’s elderly population is happening at a

time of rapid increase in urbanization and industrialization,

all of which have weakened traditional family support networks

(Jackson 2010). Because of a limited institutional care

system, China’s elderly have predominantly received care in

the home; only 2 percent are institutionalized. The elderly

living in institutions are more likely to reside in urban areas,

have less access to family-care resources, and exhibit poorer

health than community-residing elders (Gu, Dupre, and Liu

2007). Yet, according to Gu and colleagues, poor health is

not the primary indicator of institutionalization. The elderly

who remain in the community are able to do so primarily

because they have familial support and care. But as the elderly

population continues to grow and the availability of family

caregivers decreases, more elderly with poor health will need

to seek care in institutions.

">

">