Apoorva Jadhav

Senior Fellow

November 25, 2025

Senior Fellow

The story of modern parenthood is increasingly being written in clinics, not bedrooms. Nowhere is this transformation more vivid than in India, where fertility sits at just 1.9 children per woman, a far cry from the 5.8 fertility rate1 that inspired the blockbuster Population Bomb in 1968.2 Worlds away from the “hellish” scenario described in that book’s opening passage, India is now home to a booming middle class with a better quality of life. Consider this: 61% of India’s total population will be middle class by 2047, nearly double today’s rate of 31%.3 This economic blossoming has given rise to a vast, growing population of Indians demanding infertility treatments. As a result, the fertility sector has ballooned into a massive economic powerhouse, equipped with state-of-the-art technology,4 private-equity backing,5 innovative services (including the nation’s first “at home IVF” offering6) and surrogacy centers.

Globally, with the discourse on population decline well underway,7,8 you would be well within reason to think that one of the major issues plaguing governments today is how to boost birthrates. Merits of such thinking aside, given that one in six people worldwide will be over the age of 60 in just five years,9 this concept tracks statistically. But what if I told you that the same number of people—one in every six on Earth—are affected by infertility in their lifetime?10 Still, infertility receives nowhere near the attention or funding of fertility decline or aging despite asking the same fundamental question: How should governments and institutions support people in having the number of children they desire?

Broadly, infertility is defined as a disease of the male and/or female reproductive system based on a prolonged period of not reaching pregnancy or live birth despite unprotected sex; however, the precise definition and methods used to estimate its frequency vary across research studies.11 The vagueness of some of its components—”prolonged period” (I can just hear demographers scream, “What’s the denominator?!”) and other terms—underscores the first challenge: measurement. If we can’t accurately quantify the problem in simple terms, how can we prioritize it as a problem worthy of time and investment amidst so many competing priorities? How can we measure infertility in a meaningful way?

Thankfully, progress has been made in this arena. A new report on measuring infertility by the World Health Organization (WHO)12 recommends a specific time period (12 months), suggests targeted methodologies, and even provides guidance for national surveys, including recommended questions that are easily understood across contexts and help with data disaggregation, which can give us more nuanced insights on who is affected. With this comprehensive guidance, we now have the tools in hand to measure infertility more accurately than ever before. Additionally, WHO will be releasing guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of infertility on November 28, a massive step forward to guide countries in ensuring equitable, evidence-based care for individuals and couples with infertility.

Which leads us to the more challenging set of solutions to counter stigma — unspoken yet omnipresent regardless of context. To understand the roots of the stigma around infertility, it is important to understand the power of its converse. Parenthood—and motherhood specifically—still cements social standing in many societies. Often, it is a sociocultural obligation that is linked to inheritance rights, and the failure to achieve it is tied to family shame, marital instability, and more.

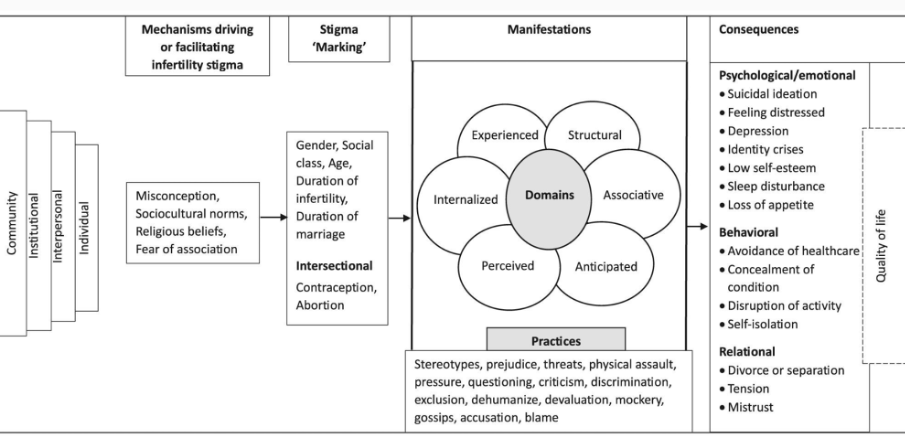

Infertility—whether perceived or “real” (more on this distinction later)—is seen as a social and moral failure, particularly borne by women.13 Researchers synthesized evidence from Africa14 to conclude that infertility is not only a medical condition, but a profound social crisis. Their framework for infertility in Africa (below) could be adapted for use in other places, supporting interventions at the individual, interpersonal, institutional, and community levels.

Source: Emmanuel Ekpor et al., “Experience of Infertility-Related Stigma in Africa: A Systematic Review and Mixed Methods Meta-Synthesis,” International Health 17, no. 6 (2025): 903–13.

There is good news in this arena as well. Low- and middle-income countries have been steadily increasing their efforts to address infertility stigma in recent years, with a recent evidence review identifying effective multilevel programs, from supporting men and women in community and church groups to empowering women financially to influencing legislation.15

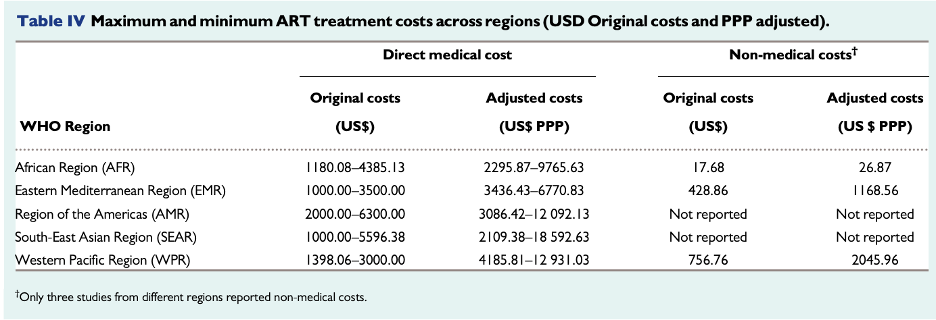

That last point is quite possibly the most exciting—and challenging—piece of the puzzle yet. The cost of various assisted reproductive technology (ART) is prohibitive for most (see figure below), broadening existing inequities in health care access. In the United States alone, this could also contribute to the growing debate about which population is declining16 and who gets to have children when they desire (spoiler alert: more inequities17). A recent review of patient costs for ART in LMICs found that, in countries where government financing for ART exists, patients spent approximately half of their average annual income on one ART cycle; meanwhile, patients in countries without this support spent double their average annual income. Further, patients in poorer countries were more likely to face higher ART costs, compounding inequities in access to care. Notably, despite potentially catastrophic costs, many still decided to pursue treatment—another illustration of the power of societal pressures around fertility.18

Source: Purity Njagi et al., “Financial Costs of Assisted Reproductive Technology for Patients in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review,” Human Reproduction Open 2023, no. 2 (2023).

Another recent study in LMICs19 reported this stunning statistic: less than 1.5% of Africa’s population has access to ART. Compare this to South Asia, where countries like India have become models for expanding access to low-cost care.20 How can these innovations cross borders—and not just for the rich?

Earlier, I mentioned there is a distinction between perceived infertility versus “real” infertility. Only the privileged few—with access to clinics and the money and time for care—can afford a “real,” medical fertility diagnosis. Further, the conversation is difficult to broach with one’s partner for fear of shame or worse (see “the stigma challenge” above). Thus, many individuals, particularly young people, base their infertility on perception, citing their past reproductive or contraceptive behaviors,21 a few instances of “missed conceptions” after unprotected sex,22 or even supernatural factors.23 There is agreement that more needs to be done to promote body literacy among youth and to train providers to counsel clients on myths and misconceptions about infertility. But the reality is that providers don’t have enough time with their patients—and infertility counseling doesn’t often enter the conversation, despite guidelines.24

Amidst the current fertility panic, two areas emerge as key to helping countries navigate infertility concerns in their populations:

One of the recurring themes in research has been the lack of political will to prioritize infertility as a health issue due to competing priorities and dwindling resources. Infertility is more than “just” a health issue—it is a social one. Improving school curricula on body literacy to include discussions on infertility myths and misconceptions can lead to increased contraceptive use (something that many policymakers care about). LMICs grappling with the downstream or imminent concern of low fertility and population decline can look to countries such as South Korea and Japan, which are helping subsidize infertility treatments in insurance plans. Countries with existing ART services need to improve access to high-quality services for all. This may require significant investment (more below), including in improving financing and regulatory frameworks. Many LMICs have ART centers operating without appropriate regulations and guidelines, affecting pricing as well as quality of care. Costs of running ART centers are further influenced by the complexity of the procedures offered and the need for highly skilled staff, equipment, and imported drugs.25 Therefore, closing these policy gaps—from education and subsidization to robust regulation—is essential to ensuring equitable access to necessary, high-quality infertility care for all citizens. Some countries are making progress towards the policy framework for infertility care, with news just this month that Kenya’s National Assembly passed the Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Bill, 2022, which attempts to create a legal framework for ART and services such as IVF and surrogacy26.

Recent, exciting advances in low-cost diagnostics and treatment from infertility would benefit from significant donor investment to test and scale up, including international efforts to bring ART to low-resource settings. For instance, the Walking Egg project27 aims to reach the goal of “global access to infertility care,” the INVOcell—billed as the first FDA-cleared medical device for fertility treatment via intravaginal culture—has shown promise in Colombia and Pakistan,28 and various initiatives from India29 can be adapted for other contexts.

In just the last few months, in separate initiatives, two major donors—the Gates Foundation30 and Pivotal Ventures31—have announced a combined $2.6 billion in new funding for work that addresses women’s health issues. While infertility is most certainly not a woman’s issue alone, this is an exciting challenge for innovators, researchers, and governments to think about sexual and reproductive health in broader terms, aligning more than ever with the Lancet-Guttmacher Commission’s vision of sexual and reproductive health and rights for all.32 The time is ripe to invest in advancing low-cost, effective, and affordable infertility treatments for everyone who wants them.

1. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, “Data Portal: Total Fertility Rate (1968-2030).”

2. Charles C. Mann, “The Book That Incited a Worldwide Fear of Overpopulation,” Smithsonian Magazine, January 2018.

3. Shiva Rajora, “Indian Middle Class Will Nearly Double to 61% by 2046-47: PRICE Report,” Business Standard [India].

4. Nehal Gautam, “How India’s Latest IVF Innovations Are Redefining Fertility Care,” Healthcare Radius, June 30, 2025.

5. Sowmya Ramasubramanian and Jessica Jani, “India Has Seen an Explosion of Fertility Startups. Next up: Deal Spree,” Mint, July 18, 2025.

6. Kavita Bajeli-Datt, “From Clinic to Couch: India’s First At-Home IVF Launched,” The New Indian Express, July 22, 2025.

7. The Economist, “A Contracting Population Need Not Be a Catastrophe,” September 11, 2025.

8. Marc Novicoff, “The Birth-Rate Crisis Isn’t as Bad as You’ve Heard—It’s Worse,” The Atlantic, June 30, 2025.

9. World Health Organization, “Ageing and Health,” October 1, 2025.

10. World Health Organization, “1 in 6 People Globally Affected by Infertility: WHO,” April 4, 2023.

11. C. M. Cox et al., “Infertility Prevalence and the Methods of Estimation From 1990 to 2021: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Human Reproduction Open 2022, no. 4 (2022): hoac051.

12. World Health Organization, Infertility Prevalence Estimates, 1990–2021, 2023.

13. Jungmin Lee, Seoyoung Kim, and Soo-Hyun Nam, “Living with Silence and Shame”: A Meta-Synthesis of Women’s Lived Experiences of Infertility-Related Stigma,” International Journal of Women’s Health 17 (2025): 2699–2713.

14. Emmanuel Ekpor et al., “Experience of Infertility-Related Stigma in Africa: A Systematic Review and Mixed Methods Meta-Synthesis,” International Health 17, no. 6 (2025): 903–13.

15. Trudie Gerrits, “Breaking the Silence Around Infertility: A Scoping Review of Interventions Addressing Infertility-Related Gendered Stigmatisation in Low- and Middle-Income Countries,” Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 13, no. 1 (2023): 2134629.

16. Brittany Farr, “A Demographic Moral Panic: Fears of a Majority-Minority Future and the Depreciating Value of Whiteness,” The University of Chicago Law Review, 2021.

17. Jamie M. Merkison et al., “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Assisted Reproductive Technology: A Systematic Review,” Fertility and Sterility 119, no. 3 (2023): 341–347.

18. Purity Njagi et al., “Financial Costs of Assisted Reproductive Technology for Patients in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review,” Human Reproduction Open 2023, no. 2 (2023).

19. Tendai M Chiware et al., “IVF and Other ART in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Landscape Analysis,” Human Reproduction Update 27, no. 2 (2021): 213–228.

20. Prathima Tholeti et al., “FERTILITY CARE IN LOW AND MIDDLE INCOME COUNTRIES: The Landscape of Assisted Reproductive Technology Access in India,” Reproduction & Fertility 5, no. 4 (2024).

21. Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health, “Understanding the Fear That Birth Control Causes Infertility,” University of California San Francisco, July 21, 2022.

22. Chelsea Bernhardt Polis and Laurie Schwab Zabin, “Missed Conceptions or Misconceptions: Perceived Infertility Among Unmarried Young Adults in the United States,” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 44, no. 1 (2012): 30–8.

23. Agency for All, “Research At-A-Glance: Reducing Infertility Stigma and Improving Reproductive Agency in Cameroon and Kenya,” 2024.

24. World Health Organization Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Center for Communication Programs Knowledge for Health Project, U.S. Agency for International Development Bureau for Global Health, Family Planning: A Global Handbook for Providers, Updated 4th ed, 2022.

25. Njagi et al., “Financial Costs of Assisted Reproductive Technology for Patients in Low- and Middle-Income Countries.”

26. “Kenya Legalises Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART): What the New Law Means,” African Leadership Magazine, November 18, 2025.

27. Willem Ombelet, “The Walking Egg Project: Universal Access to Infertility Care – From Dream to Reality,” Facts, Views and Vision in ObGyn 5, no. 2 (2013): 161–75.

28. Tendai M Chiware et al., “IVF and Other ART in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Landscape Analysis,” Human Reproduction Update 27, no. 2 (2021): 213–28.

29. Tholeti et al., “FERTILITY CARE IN LOW AND MIDDLE INCOME COUNTRIES.”

30. Gates Foundation, “Gates Foundation Announces Catalytic Funding to Spark New Era of Women-Centered Research and Innovation,” August 4, 2025.

31. Regina E. Dugan, “It’s Time for Breakthroughs in Women’s Health. Women Have Waited Long Enough,” Pivotal Ventures, September 10, 2025.

32. Ann M Starrs et al., “Accelerate Progress—Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights for All: Report of the Guttmacher–Lancet Commission, The Lancet Commissions 391, no. 10140 (2018):2642-92.