Date

August 25, 2025

At PRB, we believe demographic trends are never just numbers—they reflect actual experiences, aspirations, and policy choices. And today, few trends are as consequential as the global decline in fertility rates. Left unchecked, panic about population can lead to policies and programs that are costly and ineffective at best—and that compromise health and rights at worst. Our Smaller World webinar series is an attempt to cut through the panic by centering data and evidence in the public discourse on fertility rates.

In our first webinar, we took stock of how low fertility panic is affecting sexual and reproductive health—including in countries where fertility is still high. We unpacked fertility trends with experts from around the world, then looked to the future to understand how we can move from panic to purpose, going beyond demographic determinism to a human-centered approach that supports people’s personal, professional, and reproductive goals. This blog extends the conversation by providing expert answers to our most-asked audience questions.

Part 1, below, features insights from Traci L. Baird (President and CEO at EngenderHealth), Jessica Grose (Opinion Writer at The New York Times), Sanghamitra Singh (Chief of Programs at the Population Foundation of India), and Yohannes Dibaba Wado (Research Scientist, African Population and Health Research Center), along with PRB staff Toshiko Kaneda and Kaitlyn Patierno.

QUESTION: In the context of declining fertility rates, is there a danger that governments and donors might cut investments in sexual and reproductive health—such as teen pregnancy prevention programs—under the false perception that “the job is done”?

ANSWER (Traci L. Baird, EngenderHealth): Yes—but in different ways, depending on the actor and setting.

In regions with comparatively lower fertility, planning ministries may fear that declining population numbers will result in reduced public funding or political representation. State or local governments may deprioritize sexual and reproductive health amid competing demands, such as non-communicable diseases, aging populations, or humanitarian needs, especially if fertility is viewed as low enough to justify shifting focus.

Among donors and development partners, lower fertility rates may be seen as a signal that a country or setting has “graduated” from needing support. Funding may be shifted to a higher-fertility context in pursuit of a greater return on investment, leaving gaps in training, service delivery, and community engagement—especially for marginalized groups.

When fertility is treated as a proxy for progress, it obscures disparities in access to care: between rural and urban populations, among youth and unmarried individuals, and across socioeconomic and ethnic groups. This reality reinforces the need to regard contraceptive access and other sexual and reproductive health services as a matter of essential human rights—and to continue making the case for the myriad health, economic, educational, and social benefits of these services for all people in all places, regardless of fertility levels.

QUESTION: We received a lot of questions about gender dynamics and fertility. Do men’s preferences around family size and their decision-making power factor into actual fertility rates? Do gender differences in ideal family size have implications for reproductive health policy?

ANSWER (Toshiko Kaneda and Kaitlyn Patierno, PRB): We know gender dynamics—including differences in preferences and power—affect fertility rates around the world. But the nature of the relationship is complex, nuanced, and not quite as well understood as you might think.

In low-income countries, where fertility is generally higher, evidence suggests that greater gender equality contributes to fertility decline. In high income countries, where fertility tends to be lower, the relationship between gender equality and fertility remains unclear, with inconsistent patterns emerging in different countries and cultures. Across the board, we know men’s preferences and decision-making power matter—but how and how much they matter depends a great deal on the context.

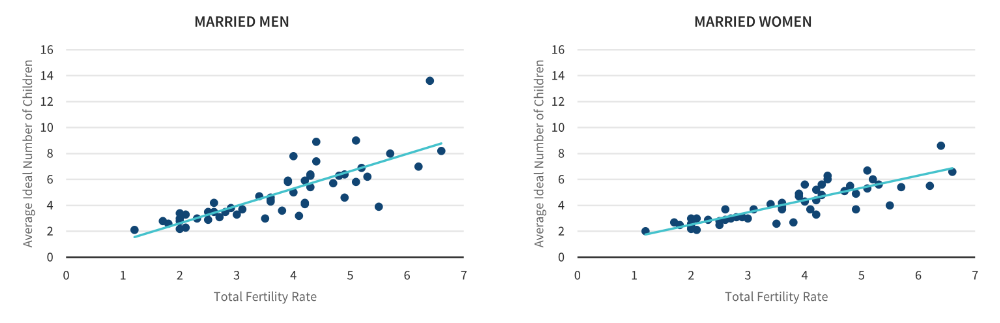

Let’s look at low- and middle-income countries with recent DHS data. While women and men’s ideal family sizes are correlated, in most countries, men want more children than women do. These charts show total fertility rate and the average ideal number of children for married men and married women for 51 countries. While the average ideal number of children is higher for both women and men in countries with higher total fertility rates, the ideal number of children is higher for men than it is for women at every fertility level (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. REGARDLESS OF A COUNTRY’s FERTILITY RATE, MEN WANT MORE CHILDREN THAN WOMEN DO

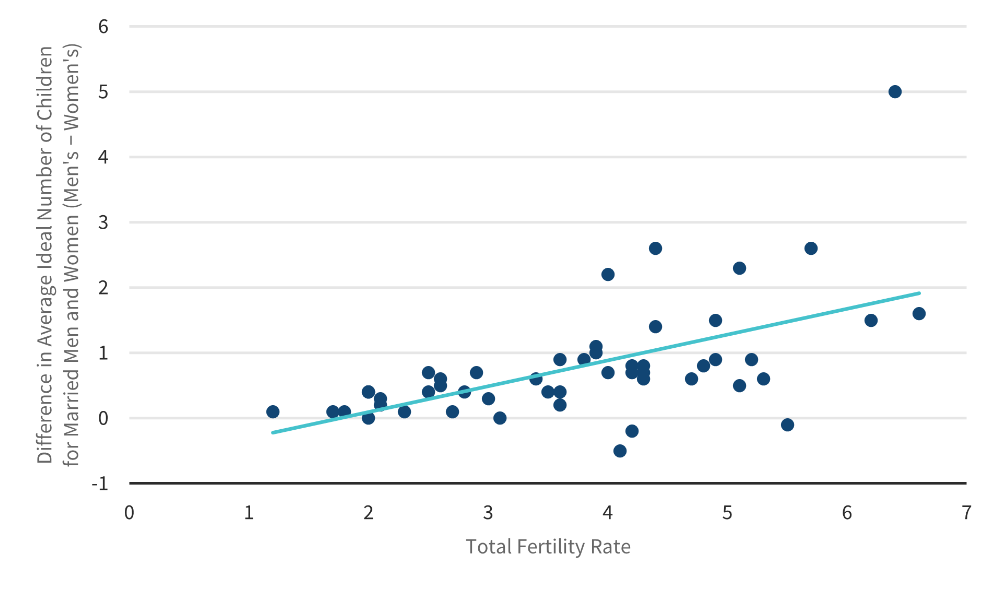

We also see that the gap between men’s and women’s ideal number of children is consistently wider in countries where total fertility rates are highest (see Figure 2). In other words, in places where people have lots of children on average, men are even more likely than women to say they want large families.

Figure 2. The Gap Between Married Men’s and Women’s Ideal Number of Children Is Wider in Countries With Higher Fertility

Across low- and middle-income countries, we find (for example, here and here and here) that women’s empowerment—using all kinds of measures including education, reproductive autonomy, contraceptive use, household decision-making power, and employment, among others—is associated with smaller ideal family size.

There’s much more we still need to know. It’s clear that family decision-making is often not gender equitable. Decisions about childbearing can be even further nuanced by various family formations, including polygamous households. And the dynamics of household bargaining over childbearing, and even the factors that affect couples’ pregnancy decisions, remain poorly understood in any context.

ANSWER (Sanghamitra Singh, Population Foundation of India): Historically, fertility has been treated as a women’s issue, with research and policy often neglecting male perspectives. Even in developed countries, studies tend to underrepresent men; for example, a qualitative study in the U.S. and Canada found that both men and women perceive fertility as a “women’s health issue.” Men often find it difficult to talk about fertility due to masculinity-related fears, and many people are unaware that men’s fertility also declines as they age.

In many South Asian contexts, a strong cultural preference for sons continues to influence family size. Analysis of India’s 2005–06 National Family Health Survey revealed that women with fewer or no sons are more likely to try for more children. This “son-preference” delays contraceptive use and increases the number of children women have because they will keep trying for a son. However, these patterns vary across the region. In Bangladesh, studies show little relationship between son preference and contraceptive use. Similarly, Vietnam and Nepal show only modest links—though Vietnamese women with two daughters are still far more likely to try for another child.

In high-fertility contexts, evidence suggests that higher gender equality is associated with lower fertility rates. Women with more autonomy—educational, financial, and reproductive—tend to delay childbirth and opt for smaller families. This dynamic also plays out at the couple level: studies show that when men support women’s decision-making on contraception, couples are more likely to adopt modern family planning methods.

Understanding and addressing gender gaps is key to crafting reproductive policies that are both effective and equitable. This includes challenging the expectation that women are solely responsible for childcare and challenging the preference for sons.

QUESTION: Jessica, you write about how regular people respond to cultural shifts. From your reporting, is fertility or “fertility panic” something that individuals actually think about when they vote on policies or candidates?

ANSWER (Jessica Grose, The New York Times): I don’t think people are thinking about their fertility or the country’s fertility too much in the voting booth. They tend to think most about short-term economic issues; sometimes this is related to family formation (“can I afford to have that third kid?”) but I very much doubt they are connecting it directly to birth rates on a deeper level. There seems to be almost no attention paid to Social Security’s funding issues, for example. Both our political parties here in the U.S. vow to protect Social Security, but no one seems to really talk about how they might be shoring it up 30 years from now if the birth dearth continues.

QUESTION: Policymakers often seek single, silver-bullet fixes to rapidly reverse fertility declines. How might such interventions come from a broader, rights-based strategy that addresses the deeper social and economic drivers of people’s reproductive choices?

Answer (Yohannes Dibaba Wado, African Population and Health Research Center): Policymakers may be drawn to quick solutions to address declining fertility rates, but these approaches often overlook the complex and deeply rooted factors that shape reproductive decisions. People’s choices on whether and when to have children are influenced by a range of social, economic, cultural, and gender-related dynamics. As such, a more holistic and sustainable approach—grounded in rights-based principles—is essential.

Isolated, quick-fix interventions, such as financial incentives for childbirth or extended parental leave, may cause a small and short-term rise in births but are unlikely to raise fertility in the long term. Experiences of European countries such as Spain and Italy show that such programs won’t work without also addressing deeper structural barriers, including unaffordable childcare, insecure employment, housing shortages, and persistent gender inequalities in caregiving. In general, a more effective and lasting strategy should prioritize human rights, equity, and individual agency, while also aligning reproductive policies with broader social and economic development goals.