Research Technical Assistance Center

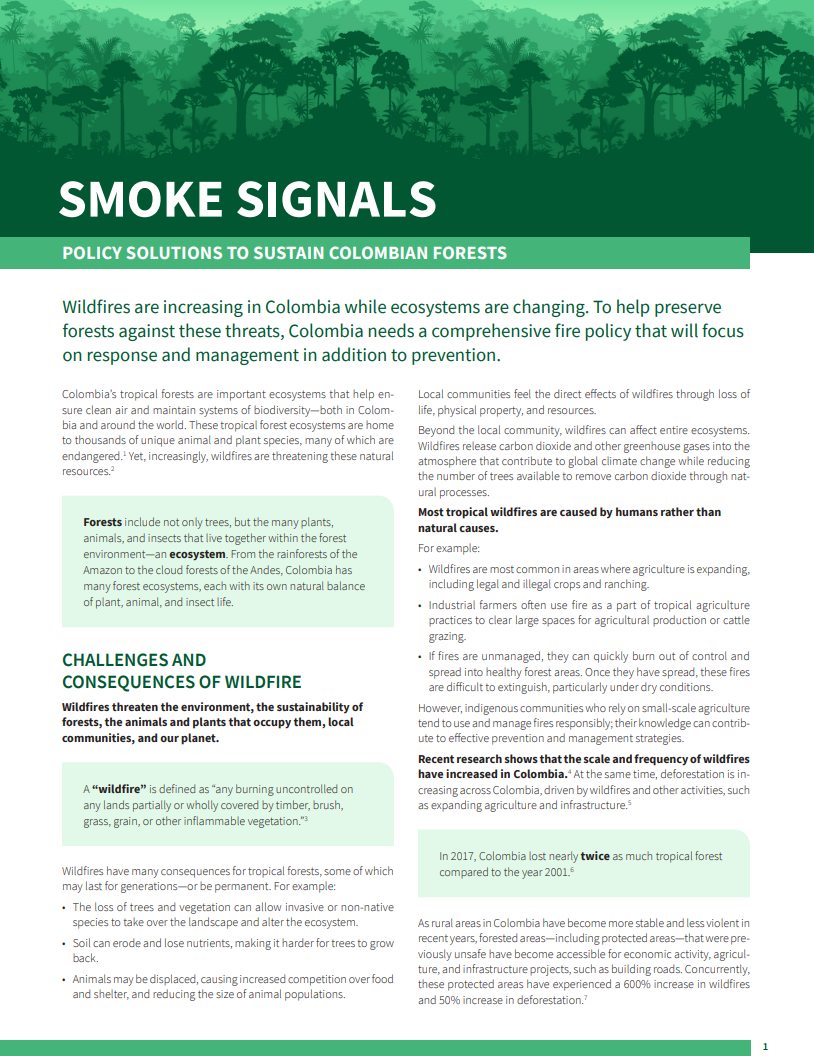

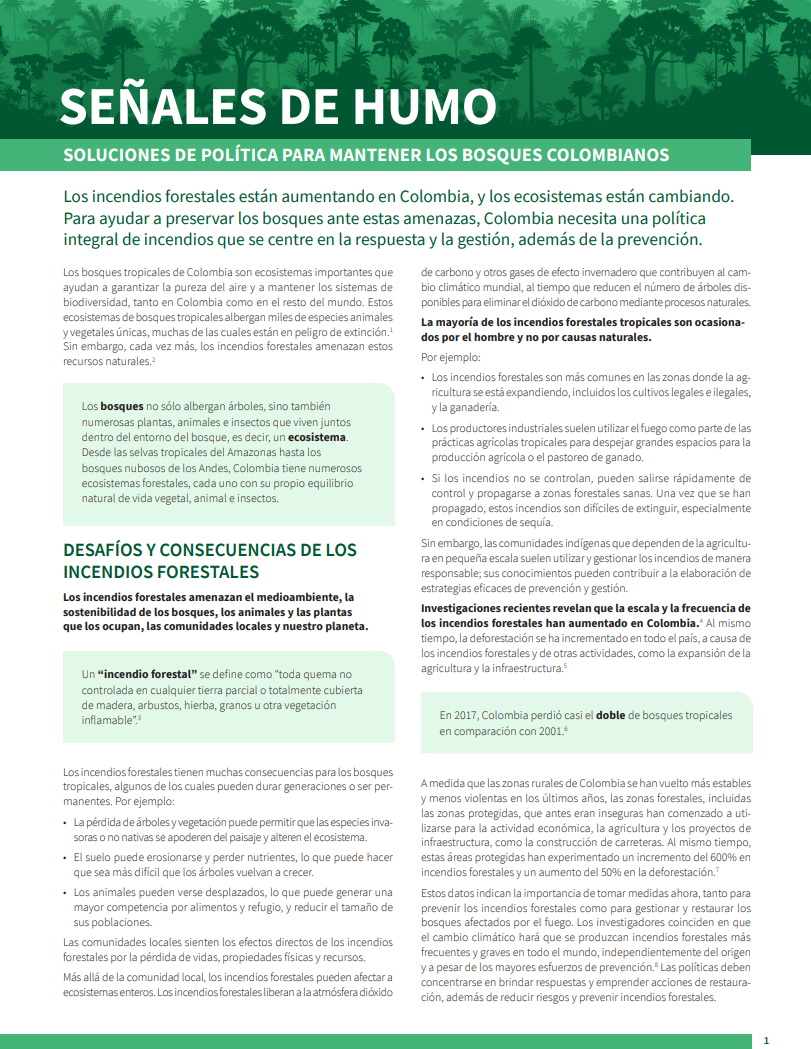

Colombia’s tropical forests are important ecosystems that help ensure clean air and maintain systems of biodiversity—both in Colombia and around the world. These tropical forest ecosystems are home to thousands of unique animal and plant species, many of which are endangered.1 Yet, increasingly, wildfires are threatening these natural resources.2

This factsheet describes policy solutions that will help preserve Colombia’s tropical forests from wildfires and their underlying causes. It includes clear recommendations for policymakers, advocates, and other stakeholders to mitigate wildfires and improve the health and biodiversity of Colombia’s forests. The factsheet is based on research led by a team at the National University of Colombia.

Notes

- IUCN 2020. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2019-3. https:// www.iucnredlist.org

- Dolors Armenteras, María Constanza Meza Elizalde, Tania Marisol González, et al. Status of Fire Ecology Knowledge in Colombia: Summary of findings & applications, Colombia: 2019

Domestic Violence in Developing Countries: An Intergenerational Crisis

(September 2004) A new comparative study using nationally representative information on domestic violence in nine developing countries finds that women whose fathers abused their mothers are twice as likely to suffer domestic abuse themselves.

The report, Profiling Domestic Violence: A Multi-Country Study, published by ORC Macro, also finds that domestic violence in these countries is highly correlated with a husband’s drunkenness and controlling behaviors. But the study did not find that a woman’s poverty, lack of education, or lack of decisionmaking control consistently elevate her risk of being abused.1

“Gender-based violence is a gender issue,” explains Kiersten Johnson, a co-author of the study and a researcher at ORC Macro. For example, the study found that women who shared the bulk of household decisions with their male partners were at a lower risk of abuse—regardless of their household’s income levels.

Domestic Violence is a Worldwide Problem

The report is based on data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in nine developing countries: Cambodia, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Egypt, Haiti, India, Nicaragua, Peru, and Zambia. These surveys, conducted mostly after 1998, collected comprehensive demographic and health data from women ages 15 to 49. In addition, information was collected on “empowerment” indicators such as education, employment, and participation in household decisionmaking.

Researchers also asked the women about their experience of domestic violence throughout their adult lives, including detailed questions about their experience of physical, sexual, and emotional violence within their current relationships. The percentages of women who said an intimate partner had ever abused them ranged from 48 percent in Zambia and 44 percent in Colombia to 18 percent in Cambodia and 19 percent in India. (A 1998 Commonwealth Fund study put levels of similar violence in the United States at 31 percent.2)

More than one in six married women in each country that was studied reported being pushed, shaken, slapped, or targeted with a thrown object by their male partners. At least one in 10 has been threatened or publicly humiliated by their husbands.

Co-author Sunita Kishor, a senior gender specialist at ORC Macro, cautioned that survey questions differed across some of the countries, making absolute comparisons of domestic-abuse prevalence problematic. But Profiling Domestic Violence makes clear that domestic violence remains a problem in these nine countries—and that in at least several of them, women are socialized into accepting its legitimacy under some circumstances.

“Educated women tend to disagree [with the practice of domestic abuse] more, but it’s not as if you get a zero-level of disagreement even among them,” says Kishor. “In most countries, the gender-role norm violation that woman are most likely to agree with as deserving of a beating is a woman’s neglect of her children. This is very, very telling—there’s a huge buy-in to the care of children being a very fundamental duty of women.”

Culture of Violence ‘Akin to Second-Hand Smoke’

The wealth of data collected by DHS also enabled Kishor and Johnson to identify common global risk factors for domestic violence—all of which, they stress, are largely beyond a woman’s control.

“Often there’s this belief that you see in public discourse that women who are beaten are in some way to blame—they’re too fat or unattractive, for example,” says Johnson. “But it’s not any one characteristic or aspect of your life. Instead, there are multiple factors at the individual, husband, and family level—including your ‘inheritance’—that are dynamically interacting.”

By “inheritance,” Johnson means a woman’s experience as a child of her mother’s abuse. Such experience, Kishor says, has “tremendous intergenerational implications.”

“I don’t think enough attention is being paid to these matters,” says Kishor. “The data shows that even exposure to a mother’s experience of abuse, not just firsthand violence, almost doubles your risk [of being abused yourself]. It’s akin to the literature about secondhand smoke—even exposure to it can have ill-effects” (see Table 1).

Table 1

Percentages of ever-married women age 15-49 who experienced spousal violence ever and in the past 12 months, by whether their mother was ever beaten by their father

| Family History | Cambodia | Colombia | Dominican Republic |

Haiti | Nicaragua | Peru |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever Experienced Spousal Violence | ||||||

| Father beat mother | ||||||

| No | 15.2 | 36.1 | 20.0 | 27.0 | 27.4 | 35.8 |

| Yes | 29.7 | 55.4 | 36.3 | 37.8 | 36.6 | 50.0 |

| Don’t know | 20.7 | 46.5 | 27.9 | 32.1 | 35.4 | 46.3 |

| Experienced Violence in the Past 12 Months | ||||||

| Father beat mother | ||||||

| No | 13.1 | u | 9.2 | 20.5 | 11.4 | u |

| Yes | 28.1 | u | 21.6 | 33.2 | 17.2 | u |

| Don’t know | 17.7 | u | 18.2 | 22.8 | 15.5 | u |

u = Unknown (not available)

Note: Data not available for remaining three countries studied in report.

Profiling Domestic Violence also found that other common correlates of domestic abuse—besides having husbands who frequently get drunk or exhibit controlling behaviors (such as limiting her outside contact or repeatedly accusing her of infidelity)—include:

- Being married more than once;

- Being married young;

- Having multiple children; or

- Being older than your husband.

In addition, Kishor and Johnson found that many abused women in developing countries do not seek help, ranging from 41 percent in Nicaragua to 78 percent in Cambodia. And those who do reach out often contact people they know rather than health professionals.

Disempowerment and Violence: No Clear Connection

Surprisingly, several measures of female empowerment—employment, education, or attitudes related to gender equity, such as believing that women have the right to refuse sex to their husbands—did not directly correlate in the study with a reduced risk of abuse. And women who make most of their household’s decisions alone—such as whether to make large purchases or to have another child—were victims of domestic violence at the same rate as those with little say in the allocation of their family’s resources. Instead, the study found that women who made decisions jointly with their male partners suffered far less abuse.

“The causality is not clear from these data between increased risk of abuse for women who make most of the decisions alone,” Kishor says. “Is it because she is in such a dysfunctional relationship that she is forced into taking charge? Or is it because she’s taking the decisions alone that she’s actually being beaten?” This uncertainty, she adds, raises questions about conventional indices of empowerment.

“We need to be looking closely at a lot of these indicators and asking what they’re really telling us in different contexts,” Kishor says. “While empowerment usually implies that you are in control of your life, the data suggest that, within a marital context, ‘dominating’ [these] decisions may not equate to empowerment.”

The Health Consequences of Abuse

The study found clearer connections between abuse and degraded health for victimized women and their children. For instance, women in almost all the surveyed countries who had experienced abuse from their intimate partners had higher rates of unwanted births and nonlive births (by 33 percent to 72 percent) than those who had never been abused.

Women who experienced violence were also more likely to have had sexually transmitted infections, their pregnancies were substantially less likely to have received first-trimester antenatal care, and their children between the ages of 12 months and 35 months were less likely to have been fully vaccinated. The children of abused women were also more likely to die before age 5.

Both authors stress that including national domestic violence statistics alongside health and demographic information is a large step forward in addressing the roots of abuse.

“Up until recently, there wasn’t the kind of impetus or interest in this kind of data, or even the recognition of domestic violence as an issue of public health and development,” Johnson says. “It’s important to know that there are multiple factors involved, and thus multiple arenas in which interventions can occur.”

Robert Lalasz is a senior editor at PRB.

References

- Sunita Kishor and Kiersten Johnson, Profiling Domestic Violence: A Multi-Country Study (Columbia, MD: ORC Macro, 2004).

- Karen Scott Collins et al., Health Concerns Across a Woman’s Lifespan: The Commonwealth Fund 1998 Survey of Women’s Health, accessed at www.cmwf.org/usr_doc/Healthconcerns_surveyreport.pdf, on Sept. 14, 2004.

For More Information

Profiling Domestic Violence: A Multi-Country Study is available at www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/OD31/DV.pdf.

Colombia Faces Prospects of More Population Displacement

Date

March 2, 2002

Author

Yvette Collymore

Former Senior Editor

Focus Area

Already one of the world’s major centers of displaced people, Colombia faces the likelihood that the latest escalation of a multifaceted civil war will force even more people from their homes and increase the risks of illness and death.

This country of some 43 million people that borders five countries — Venezuela, Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, and Panama — has endured nearly four decades of violence that has uprooted at least 2 million people and caused the deaths of some 30,000 others, according to the U.S. Committee for Refugees (USCR).

Forced migration often places women (especially pregnant women), children, the elderly, the disabled, and the chronically ill in situations of outright desperation. The New York-based Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children says the trauma and upheaval of war forces hundreds of thousands of Colombian women and their children from rural areas into the cities every year. In many cases, a woman will flee her village after a husband, brother, father, or son has been kidnapped or killed.

“Traumatized and terrorized, she will leave as quickly as possible — often within hours — for a hastily chosen destination. Upon arrival in that destination, she will be lucky to count on the help of a friend or relative for immediate temporary shelter,” says the Commission. “Just as likely, she will find no support whatsoever and will have to scramble to find a foothold in the barrios (slums) or at the edges of smaller towns.”

In its country reports on human rights released March 4, the U.S. State Department estimates that between 275,000 and 347,000 Colombians fled their homes in 2001 as a result of violence and instability in rural areas, with roughly one-quarter of these movements occurring in massive displacements. The report notes the difficulty in obtaining exact numbers of displaced people, however, since some are uprooted more than once, and many do not register with the government or other agencies. The World Health Organization (WHO) also reports that much of the displacement within Colombia occurs “silently,” with uprooted people simply merging unnoticed into their new situations.

Around the world, the number of internally displaced people — an estimated 20 million to 25 million — is higher than the estimated 14 million refugees who leave their countries, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Only two countries have more displaced nationals than Colombia (2 million): Sudan with 4 million and Angola with 2.3 million. Other countries with large displaced populations include Congo (1.8 million), Eritrea (1.1 million), and Afghanistan (956,600), according to UNHCR.

Like other refugees, internally displaced people leave their homes to avoid the effects of civil war, persecution, human rights abuses, drought, or other disasters. The USCR notes that displacement in Colombia is directly related to conflict, political violence, and human rights abuses. The conflict involves left-wing guerrillas, right-wing paramilitaries, and the Colombian armed forces.

In its report on human rights in Colombia in 2001, the U.S. State Department refers to a number of “serious problems” facing the Colombian people, including abuse of children; child prostitution; and widespread violence and extensive societal discrimination against women, indigenous people, and minorities.

Child labor is a nationwide problem as is trafficking in women and girls for the purpose of sexual exploitation, says the report. “Social cleansing” killings of street children, prostitutes, homosexuals, and others deemed socially undesirable by paramilitary groups, guerrillas, and vigilante groups also continue to be a major issue.

Unlike international refugees, internally displaced people have no special status and no specific legally binding instrument guarantees protection or assistance. Internally displaced populations are therefore highly vulnerable. Although primary responsibility for these people rests with national governments, they may get no public or other attention because governments may have little capacity or interest in assisting them. Often, they remain invisible or inaccessible.

People’s health status and health care are of vital concern in any crisis. The arrival of large numbers of people in a community can strain the health system, and the newcomers and residents also begin competing for access to food, potable water, shelter, and environmental resources. WHO notes that HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria are of paramount concern in situations of displacement and are difficult to address.

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) notes that though Colombia offers access to health care for all of its citizens, regulations require that each person be properly identified. Afraid of yet again becoming a target for armed groups in the civil war, Colombia’s displaced people generally avoid health care benefits. According to PAHO’s 2001 Country Health Profile for Colombia, only 22.1 percent of displaced households receive medical care.

PAHO says that a study conducted in Colombia between 1985 and 1994 highlighted a number of issues facing displaced people. The survey found that 6.7 percent of displaced households had lost a spouse or one child through violence before they migrated, and 1,570 orphans, abandoned children, or youth had to take responsibility for the family. Of the displaced population, 69.3 percent had their own homes before they were uprooted — a percentage that dropped to 28.7 percent after they moved. Before displacement, 40.7 percent were involved in agricultural production, either earning wages or as owners of small or medium-sized plots of land, and 10.0 percent had small or medium-sized businesses. Following displacement, 22.5 percent became street vendors, 12.9 percent became laborers, and only 10.7 percent continued to be engaged in agricultural activities.

Organizations working to improve the lives of Colombia’s displaced people recommend that the needs of children and women be made an urgent priority. They urge greater support for job training and loan programs that might enable women to improve their circumstances. For displaced children, access to education and to productive activities is key to fending off the many risks they face, including those of forced labor and sexual exploitation.

Colombia Facts and Figures

| Population, mid-2001 (millions) | 43.1 |

| Projected population, 2025 (millions) | 59.7 |

| Population 15-49 with HIV/AIDS, end-1999 (%) | 0.3 |

| Infant mortality rate (deaths per 1,000 live births by age 1) | 21 |

| Total fertility rate (average number of children per woman) | 2.6 |

| Married women 15-49 using modern contraception (%) | 63 |

| Population 16-20 currently attending school (%) | 42 |

| Households with a television (%) | 83 |

| Households with a telephone (%) | 52 |

| Households with a refrigerator (%) | 64 |

Source: 2001 World Population Data Sheet, Population Reference Bureau; Education and household statistics from Salud Sexual y Reproductiva en Colombia: Resultados, Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud 2000.

References

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), “Country Health Profile 2001: Colombia,” accessed at www.paho.org on March 6, 2002.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Internally Displaced Persons,” accessed at www.unhcr.ch, on March 6, 2002.

U.S. Committee for Refugees (USCR), “Principal Sources of Internally Displaced Persons,” accessed at www.refugees.org, on March 6, 2002.

Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children, “A Charade of Concern: The Abandonment of Colombia’s Forcibly Displaced,” accessed at www.womenscommission.org, on March 6, 2002.

World Bank, “Street Children in Central America: An Overview,” accessed at http://lnweb18.worldbank.org/External/lac/lac.nsf/

8ffa96b85a80b19d852567fb00738261/19e661ab7bbb25de852568cf006ad8a8?OpenDocument, on Jan. 22, 2002.

World Health Organization (WHO), “Internally Displaced Persons, Health and WHO,” paper presented at the Humanitarian Affairs Segment of ECOSOC 2000, New York, July 19-20, 2000, accessed at www.who.org, on March 6, 2002.

For More Information

See “Women, War, and HIV/AIDS: Judy Benjamin, of the Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children, Examines the Connections,” at www.prb.org.