Research Technical Assistance Center

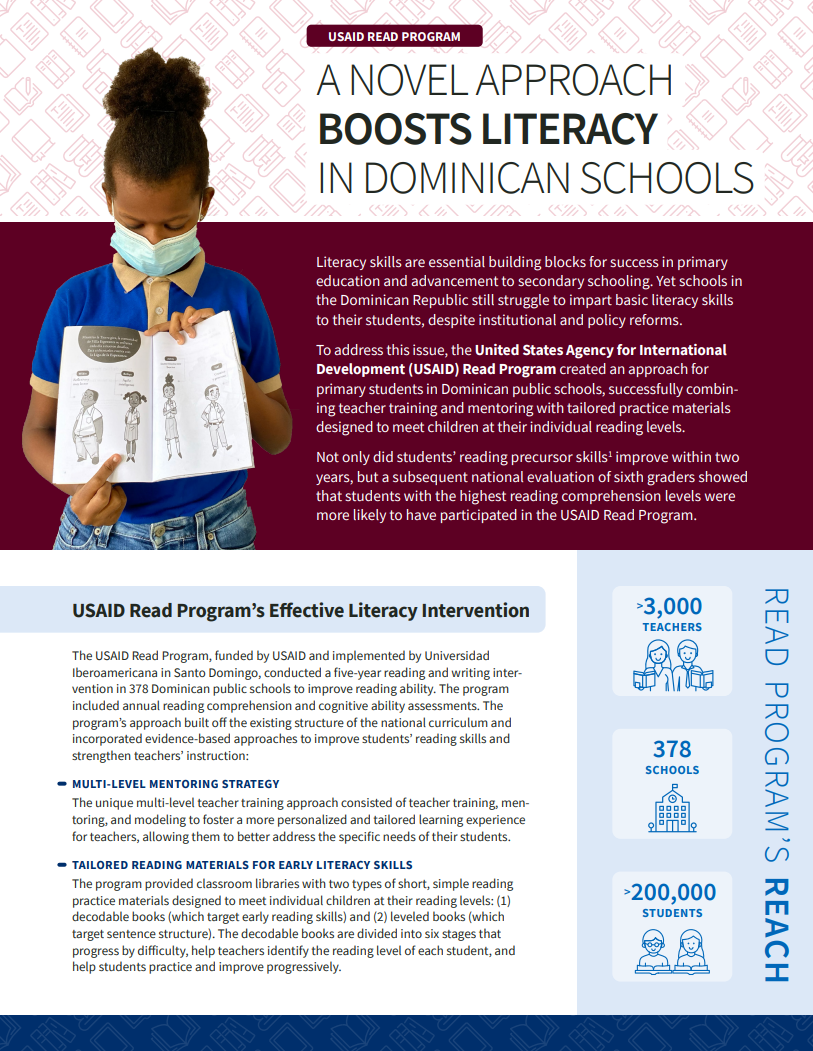

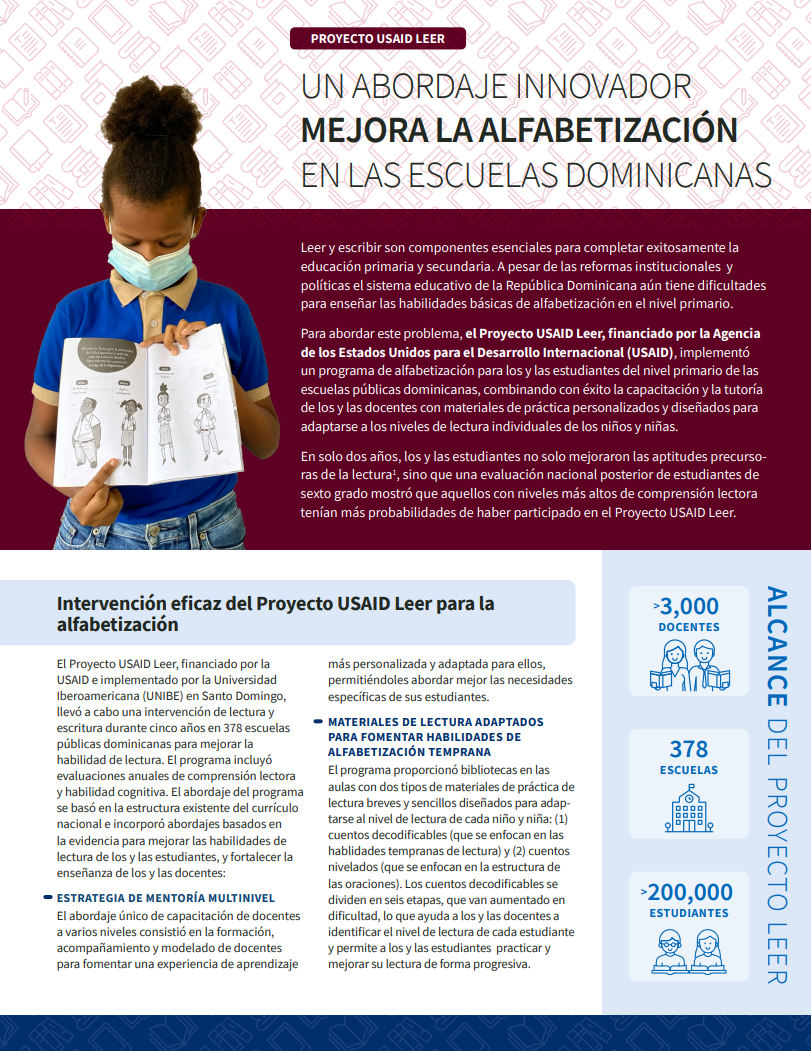

Literacy skills are essential building blocks for success in primary education and advancement to secondary schooling. Yet schools in the Dominican Republic still struggle to impart basic literacy skills to their students, despite institutional and policy reforms. To address this issue, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Read Program created an approach for primary students in the Dominican Republic’s public schools, successfully combining teacher training and mentoring with tailored practice materials designed to meet children at their individual reading levels. Not only did students’ reading precursor skills improve within two years, but a subsequent national evaluation of sixth graders showed that students with the highest reading comprehension levels were more likely to have participated in the USAID Read Program.

This factsheet, available in English and Spanish, shares the approach and success of the literacy intervention and provides recommendations to take the program’s success nationwide in the Dominican Republic.

Domestic Violence in Developing Countries: An Intergenerational Crisis

(September 2004) A new comparative study using nationally representative information on domestic violence in nine developing countries finds that women whose fathers abused their mothers are twice as likely to suffer domestic abuse themselves.

The report, Profiling Domestic Violence: A Multi-Country Study, published by ORC Macro, also finds that domestic violence in these countries is highly correlated with a husband’s drunkenness and controlling behaviors. But the study did not find that a woman’s poverty, lack of education, or lack of decisionmaking control consistently elevate her risk of being abused.1

“Gender-based violence is a gender issue,” explains Kiersten Johnson, a co-author of the study and a researcher at ORC Macro. For example, the study found that women who shared the bulk of household decisions with their male partners were at a lower risk of abuse—regardless of their household’s income levels.

Domestic Violence is a Worldwide Problem

The report is based on data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in nine developing countries: Cambodia, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Egypt, Haiti, India, Nicaragua, Peru, and Zambia. These surveys, conducted mostly after 1998, collected comprehensive demographic and health data from women ages 15 to 49. In addition, information was collected on “empowerment” indicators such as education, employment, and participation in household decisionmaking.

Researchers also asked the women about their experience of domestic violence throughout their adult lives, including detailed questions about their experience of physical, sexual, and emotional violence within their current relationships. The percentages of women who said an intimate partner had ever abused them ranged from 48 percent in Zambia and 44 percent in Colombia to 18 percent in Cambodia and 19 percent in India. (A 1998 Commonwealth Fund study put levels of similar violence in the United States at 31 percent.2)

More than one in six married women in each country that was studied reported being pushed, shaken, slapped, or targeted with a thrown object by their male partners. At least one in 10 has been threatened or publicly humiliated by their husbands.

Co-author Sunita Kishor, a senior gender specialist at ORC Macro, cautioned that survey questions differed across some of the countries, making absolute comparisons of domestic-abuse prevalence problematic. But Profiling Domestic Violence makes clear that domestic violence remains a problem in these nine countries—and that in at least several of them, women are socialized into accepting its legitimacy under some circumstances.

“Educated women tend to disagree [with the practice of domestic abuse] more, but it’s not as if you get a zero-level of disagreement even among them,” says Kishor. “In most countries, the gender-role norm violation that woman are most likely to agree with as deserving of a beating is a woman’s neglect of her children. This is very, very telling—there’s a huge buy-in to the care of children being a very fundamental duty of women.”

Culture of Violence ‘Akin to Second-Hand Smoke’

The wealth of data collected by DHS also enabled Kishor and Johnson to identify common global risk factors for domestic violence—all of which, they stress, are largely beyond a woman’s control.

“Often there’s this belief that you see in public discourse that women who are beaten are in some way to blame—they’re too fat or unattractive, for example,” says Johnson. “But it’s not any one characteristic or aspect of your life. Instead, there are multiple factors at the individual, husband, and family level—including your ‘inheritance’—that are dynamically interacting.”

By “inheritance,” Johnson means a woman’s experience as a child of her mother’s abuse. Such experience, Kishor says, has “tremendous intergenerational implications.”

“I don’t think enough attention is being paid to these matters,” says Kishor. “The data shows that even exposure to a mother’s experience of abuse, not just firsthand violence, almost doubles your risk [of being abused yourself]. It’s akin to the literature about secondhand smoke—even exposure to it can have ill-effects” (see Table 1).

Table 1

Percentages of ever-married women age 15-49 who experienced spousal violence ever and in the past 12 months, by whether their mother was ever beaten by their father

| Family History | Cambodia | Colombia | Dominican Republic |

Haiti | Nicaragua | Peru |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever Experienced Spousal Violence | ||||||

| Father beat mother | ||||||

| No | 15.2 | 36.1 | 20.0 | 27.0 | 27.4 | 35.8 |

| Yes | 29.7 | 55.4 | 36.3 | 37.8 | 36.6 | 50.0 |

| Don’t know | 20.7 | 46.5 | 27.9 | 32.1 | 35.4 | 46.3 |

| Experienced Violence in the Past 12 Months | ||||||

| Father beat mother | ||||||

| No | 13.1 | u | 9.2 | 20.5 | 11.4 | u |

| Yes | 28.1 | u | 21.6 | 33.2 | 17.2 | u |

| Don’t know | 17.7 | u | 18.2 | 22.8 | 15.5 | u |

u = Unknown (not available)

Note: Data not available for remaining three countries studied in report.

Profiling Domestic Violence also found that other common correlates of domestic abuse—besides having husbands who frequently get drunk or exhibit controlling behaviors (such as limiting her outside contact or repeatedly accusing her of infidelity)—include:

- Being married more than once;

- Being married young;

- Having multiple children; or

- Being older than your husband.

In addition, Kishor and Johnson found that many abused women in developing countries do not seek help, ranging from 41 percent in Nicaragua to 78 percent in Cambodia. And those who do reach out often contact people they know rather than health professionals.

Disempowerment and Violence: No Clear Connection

Surprisingly, several measures of female empowerment—employment, education, or attitudes related to gender equity, such as believing that women have the right to refuse sex to their husbands—did not directly correlate in the study with a reduced risk of abuse. And women who make most of their household’s decisions alone—such as whether to make large purchases or to have another child—were victims of domestic violence at the same rate as those with little say in the allocation of their family’s resources. Instead, the study found that women who made decisions jointly with their male partners suffered far less abuse.

“The causality is not clear from these data between increased risk of abuse for women who make most of the decisions alone,” Kishor says. “Is it because she is in such a dysfunctional relationship that she is forced into taking charge? Or is it because she’s taking the decisions alone that she’s actually being beaten?” This uncertainty, she adds, raises questions about conventional indices of empowerment.

“We need to be looking closely at a lot of these indicators and asking what they’re really telling us in different contexts,” Kishor says. “While empowerment usually implies that you are in control of your life, the data suggest that, within a marital context, ‘dominating’ [these] decisions may not equate to empowerment.”

The Health Consequences of Abuse

The study found clearer connections between abuse and degraded health for victimized women and their children. For instance, women in almost all the surveyed countries who had experienced abuse from their intimate partners had higher rates of unwanted births and nonlive births (by 33 percent to 72 percent) than those who had never been abused.

Women who experienced violence were also more likely to have had sexually transmitted infections, their pregnancies were substantially less likely to have received first-trimester antenatal care, and their children between the ages of 12 months and 35 months were less likely to have been fully vaccinated. The children of abused women were also more likely to die before age 5.

Both authors stress that including national domestic violence statistics alongside health and demographic information is a large step forward in addressing the roots of abuse.

“Up until recently, there wasn’t the kind of impetus or interest in this kind of data, or even the recognition of domestic violence as an issue of public health and development,” Johnson says. “It’s important to know that there are multiple factors involved, and thus multiple arenas in which interventions can occur.”

Robert Lalasz is a senior editor at PRB.

References

- Sunita Kishor and Kiersten Johnson, Profiling Domestic Violence: A Multi-Country Study (Columbia, MD: ORC Macro, 2004).

- Karen Scott Collins et al., Health Concerns Across a Woman’s Lifespan: The Commonwealth Fund 1998 Survey of Women’s Health, accessed at www.cmwf.org/usr_doc/Healthconcerns_surveyreport.pdf, on Sept. 14, 2004.

For More Information

Profiling Domestic Violence: A Multi-Country Study is available at www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/OD31/DV.pdf.

Caribbean Countries Pay for Successfully Addressing Population Issues

Date

April 22, 2002

Author

PRB

(April 2002) In a move that marks the Caribbean’s success in various spheres of socioeconomic activity, international funding agencies are reducing their financial support for the region’s sexual and reproductive health programs. The move could adversely affect the delivery of population services — including those designed to stop the spread of HIV/AIDS — unless alternate sources of funding are found.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), and the World Bank have all signaled that the region has achieved success in socioeconomic development (including various population activities) and therefore should not continue to receive current levels of assistance. As a result, some countries will see their assistance phased out altogether while others will have their funding reduced over time.

Population Characteristics

This process of “graduation” from international assistance follows achievements in addressing a number of population problems. Infant mortality, birth rates, and population growth have declined during the last decade or so and the decline has been rapid in some cases.1 As a consequence, population growth has slowed while life expectancy at birth continues to rise.

Total fertility rates (TFRs) are expected to decline significantly for most countries over the next decade. In Belize, for example, the average number of children per woman is estimated to decline by more than 58 percent — from 5.4 in 1980-1985 to 2.6 in 2005-2010. A decline of some 53 percent is projected for Trinidad and Tobago, with the TFR dropping from 3.2 to 1.6 during the period.2 Haiti recorded the highest number of children per woman during 1980-1985 with 6.2, but this number is expected to decline by 40 percent (to 3.6) by 2005-2010.

Crude death rates or deaths per 1,000 people are also declining in the region. Countries estimated to record the highest declines during the periods 1980-1985 and 2005-2010 include Haiti (a 42.7 percent decline), Belize (35.1 percent), Guyana (23.9 percent), and the Dominican Republic (23.5 percent).

As a direct consequence of this declining mortality (from all causes of death including AIDS), life expectancy at birth has been increasing. Guadeloupe is estimated to record the highest life expectancy at birth of 76.0 years (males) and 82.5 years (females) during 2005-2010, an increase of 10.3 percent for men and 8.3 percent for women over the figures for the 1980-1985 period. Haiti (18.2 percent for males and 17.8 percent for females) is projected to record the highest percentage change in life expectancy during the 1980-1985 to 2005-2010 period, although the actual life expectancy at birth is estimated to be a modest 59.8 years for males and 62.8 years for females during 2005-2010.3

In line with declining fertility and mortality and limited net international migration, population growth rates are expected to remain low in the Caribbean.4 Cuba is expected to record the highest decline in the population growth rate, going from 0.8 percent during 1980-1985 to 0.3 percent during 2005-2010 — a nearly 63 percent drop. Estimates for Trinidad and Tobago show the growth rate falling from 1.7 percent during 1980-1985 to 0.5 percent in 1995-2000, before rising slightly to 0.7 percent in 2005-2010. The growth rate for the Dominican Republic is expected to go from 2.3 percent in 1980-1985 to 1.3 percent during 2005-2010, while in Jamaica the rate is expected to decline from 1.5 percent to 0.9 percent.

The Price

This overall success is costing the Caribbean international support for its population activities. UNFPA prioritizes and allocates funds to developing countries according to population needs. Most Caribbean countries have been placed in category B in the last five years (mid-level need) and slated for funding reduction, while the Bahamas and Barbados have been placed in category C (low-level need) and slated for a funding phase out.5

Many international agencies use the UNFPA classification to make funding decisions. The IPPF has announced its decision to phase out funding for some Caribbean countries and drastically implement a phased reduction in funds for many others. While the IPPF decision is also the result of a reduction in funding from the Federation’s own donors, other international agencies may follow suit. These cuts are expected to have a far-reaching impact. Until recently, for example, many Caribbean family planning programs received a substantial amount of funding from the IPPF.

While some governments already provide support for these programs, many are unlikely to be able to meet the funding shortfall. Governments such as Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago already spend substantial amounts of funds on their countries’ family planning programs. Others, including Grenada and Antigua and Barbuda, allow family planning associations to import supplies without customs duties and offer other non-cash concessions.

Emerging Population Issues

While the UNFPA reclassification was based on demographic data in the early to mid-1990s, new population challenges are emerging in the region. Notable among them are population aging, HIV/AIDS, and the need to sustain the levels of fertility, mortality, population growth, and related achievements that resulted in the reclassification.

Population Aging

Falling fertility and mortality and increasing life expectancy at birth provide a good mix for population aging and for increases in the proportion of older people in the population. The proportion of the population 65 years of age and older is expected to increase throughout the region between 1990 and 2020. In the Bahamas, where the largest percentage change is expected to occur, the proportion of the population 65 years old and older is expected to increase from 4.6 percent to 9 percent over the 30-year period. Cuba and Guyana are also expected to record massive changes in the proportion of older people.6 For Cuba, the proportion will increase from 8.4 percent to 15.8 percent. In Guyana the proportion of older people is expected to increase from 3.4 percent to 7.0 percent.

The increasing proportion of older people in the population brings with it a host of socioeconomic issues that will have to be addressed by these countries, including increased demand for health care, housing, recreation, transportation and other geriatric services and programs, with inherent implications for funding.

HIV/AIDS

The Caribbean has the second highest prevalence rate of HIV/AIDS in the world (2.2 percent) after sub-Saharan Africa (8.4 percent). While there are wide variations in the region, the largest number of people living with HIV/AIDS is found in Haiti where 200,000 adults ages 15-49 and 5,200 children under 15 years have the virus (see table below).

Table 1

Estimated Number of People Living with HIV/AIDS and Deaths by Country, 1999

| People living with HIV/AIDS | Deaths | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Adults (15-49) | Adult HIV prevalence rate | Women (15-49) | Children (0-15) | All ages |

| Bahamas | 6,800 | 4.13 | 2,200 | 150 | 500 |

| Barbados | 1,700 | 1.17 | 570 | <> | 130 |

| Belize | 2,400 | 2.01 | 590 | <> | 170 |

| Cuba | 1,950 | 0.03 | 450 | <> | 120 |

| Dominican Republic | 130,000 | 2.80 | 59,000 | 3,800 | 4,900 |

| Guyana | 15,000 | 3.01 | 4,900 | 140 | 900 |

| Haiti | 200,000 | 5.17 | 67,000 | 5,200 | 23,000 |

| Jamaica | 9,700 | 0.71 | 3,100 | 230 | 650 |

| Suriname | 2,900 | 1.26 | 950 | 110 | 210 |

| Trinidad & Tobago | 7,600 | 1.05 | 2,500 | 180 | 530 |

Source: Compiled from UNAIDS and WHO Epidemiological Fact Sheets.

The Dominican Republic follows Haiti with 130,000 adults and 3,800 children living with HIV or AIDS. Countries with moderate numbers of people living with HIV/AIDS include Guyana with 15,000 adults and 140 children, Jamaica with 9,700 adults and 230 children, Trinidad and Tobago with 7,600 adults, and the Bahamas with 6,800 adults and 150 children. Barbados, Cuba, Belize, and Suriname have the fewest people living with HIV/AIDS (see table above).

AIDS-related mortality is low in the Dominican Republic and moderate to high in the other countries, especially Haiti. The largest number of AIDS deaths in 1999 occurred in Haiti (23,000 deaths) and this constituted 11.2 percent of the total number of people living with the disease that year (see table above). The Dominican Republic recorded the second largest number of deaths with 4,900, but this constituted the lowest proportion of deaths of only 3.7 percent. Death proportions from AIDS were moderately higher in Cuba (5.6 percent) and Guyana (5.9 percent). The numbers were higher in the Bahamas (500 and 7.2 percent), Barbados (130 and 7.2 percent), Suriname (210 and 7.0 percent), Trinidad and Tobago (530 and 6.8 percent), and Belize (170 and 6.8 percent).

Most local family planning associations have been dealing with HIV/AIDS prevention at the grassroots level, including through programs in schools and through community outreach projects. According to the Barbados Ministry of Education, sexual activity is rife among school children in the country: children as young as 9 years old are involved in such activity, increasing their risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.7 A survey of family planning associations indicates that many would cut services if the shortfall from declining international funding is not found elsewhere.8 HIV/AIDS services are likely to be curtailed as part of these overall service cuts.

In the meantime, governments in the region are setting up national advisory councils and national commissions on AIDS as they try to curb the epidemic’s spread and impact. Caribbean Community (CARICOM) members have also agreed to adopt a regional approach to tackling HIV/AIDS, and discussions are afoot among member states about how this regional approach would be funded and implemented. The role of the family planning associations in this new approach is unclear at this stage, but it is hoped that they would be funded to continue work at the grassroots level since they have the potential to contribute significantly to any anti-AIDS efforts.

Conclusion

The Caribbean’s success in addressing population issues was achieved with a certain level of funding, without which the gains may be lost. The end of preferential trade status with the European Union, globalization, and trade liberalization, as well as fall out from the September 11 attacks on the United States (especially in relation to tourism) are adversely affecting revenues, and there can be no guarantee that the Caribbean countries will continue to maintain their current levels of income generation and economic growth. Some of the more developed countries in the region, such as Barbados, are technically in a recession (having recorded a third consecutive year of declining economic growth).9

The problem is exacerbated by competition from other sources of government expenditure, and it is most unlikely that many governments will be able to meet the shortfalls in international funding. The results could be devastating for the region in view of the emerging population issues and the need to sustain levels of success.

David Achanfuo Yeboah is senior fellow and inter-campus coordinator of the Special Studies and Research Methods Unit at the Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies, the University of the West Indies, in Cave Hill, Barbados.

References

- 1. D. A. Yeboah, “A Demographic Profile of the Caribbean,” CARICOM Perspectives, no. 70 (2001): 104-105.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Statistical Yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean (Santiago: ECLAC, 1999); and Yeboah, “A Demographic Profile of the Caribbean.”

- ECLAC, Statistical Yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean.

- D.A.Yeboah, “A Demographic Profile of the Caribbean.

- D.A. Yeboah, “Strategies Adopted by Caribbean Family Planning Associations to Address the Challenges of Declining International Funding,” International Family Planning Perspectives (forthcoming, June 2002).

- ECLAC, Statistical Yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean; and Yeboah, “A Demographic Profile of the Caribbean.”

- Barbados Ministry of Education, A Survey of Sexual Behaviour Among School Children (Bridgetown: Ministry of Education, 2001); and Ruben del Prado, United Nations Press Conference on AIDS, Port-of-Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, December 7, 2001.

- D. A. Yeboah, “Strategies Adopted by Caribbean Family Planning Associations to Address the Challenges of Declining International Funding.”

- “Third Year of Decline: Report of the Governor of the Barbados Central Bank,” Nation (Barbados), January 31, 2002.<.li>