Germany: Beyond the Transition's End

Date

July 18, 2011

Author

Focus Areas

This article is taken from the Population Bulletin: The World At 7 Billion, which looks at the four phases of the demographic transition as descriptive of past and future population growth. Four countries are highlighted to illustrate each phase and its implications for human well-being.

Germany’s recovery from the devastation of World War II is often called an “economic miracle” because its economy is now Europe’s largest. Immigration has been an important part of the country’s modern demographic history.

Labor shortages led to a guest-worker program, which began bringing workers to West Germany from countries such as Greece, Italy, Spain, Turkey, and Yugoslavia in the late 1950s. Rather than return to their homelands, however, many of these workers brought their families to Germany. From 1960 to the early 1980s, net immigration averaged several hundred thousand per year, peaking at more than 500,000 in 1969 and 1970. Following Germany’s reunification in 1990, a new flow of migrants arrived: ethnic Germans who had been trapped behind the Iron Curtain. In 1992, net immigration neared 800,000. There was concern at the time that some of these migrants were not true ethnic Germans, but were economic migrants seeking a better life in the West. At the end of 2009, 19 percent of Germany’s population had what the German Federal Statistical Office calls a “migrant” background, which includes immigrants since 1950 and their offspring.

Germany is a dramatic example of the fourth phase of demographic transition: Countries with low or very low birth and death rates represent almost half, or 46 percent, of the world’s population.

Overview

Germany’s population stands at an estimated 81.8 million in mid-2011, the largest country in the European Union by a good margin. But that total is down from 82.3 million at the end of 2006. Germany’s principal demographic concerns today are its very low birth rate and the lack of social and cultural integration of its migrant population. Recently, Chancellor Angela Merkel stated that integration was “not working.”

Figure 1

Total Fertility Rate in Germany, 1955-2010

Source: German Federal Statistical Office.

Source: German Federal Statistical Office.

In 1964, births exceeded deaths by 486,985, the highest postwar surplus. By 1972, deaths in Germany exceeded births by 64,032, and deaths have surpassed births every year since. In 2010, the difference between births and deaths stood at -180,833. Only a positive balance of net immigration has forestalled a much more rapid population decline. As a member of the European Union (EU), Germany must also abide by the Schengen Agreement of 1985 whereby the EU has no border controls. Member states do have the right to impose certain restrictions, however. In 1995, the agreement was in force in the 25 member states. There has been some resistance to including new member states from eastern and southern Europe in the passport-free zone. The EU is now debating the Schengen status of new members Bulgaria and Romania.

Population and Policies

The fourth phase of the demographic transition is often described as an extended period of near demographic equilibrium, with fertility near the replacement level of about 2.1 children per woman. In the majority of industrialized countries, fertility fell quite rapidly throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, a transformation that was to alter demographic prospects in many countries in unforeseen ways. In the United States, fertility fell from 2.9 children per woman in 1965 to a record low of 1.7 in 1976. Germany reached a TFR of 1.7 in 1970. But while the U.S. fertility rate slowly rebounded to 2.1 in 1990 (and has remained close to that ever since), the German fertility rate did not rebound, and today is much lower, at 1.4.

Fertility in the former East and West Germany followed a very similar path up to the mid-1970s. But East Germany, under Communist rule, instituted a number of pronatalist measures such as family allowances, maternity leave, and child care subsidies. Fertility rose until the economic disruption after the country’s reunification and the subsequent out-migration from East Germany to the West.

Figure 2

Age and Sex Structure of Germany, 2009 and 2050

Sources: For 2009: German Federal Statistical Office, Statistical Yearbook 2010. For 2050: United Nations Population Division, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision (2011).

Sources: For 2009: German Federal Statistical Office, Statistical Yearbook 2010. For 2050: United Nations Population Division, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision (2011).

In western Germany, however, little was done to reverse the trend in low fertility. Fertility has remained below 1.5 children per woman since 1975, and at times considerably below. Obstacles to increasing the birth rate are similar to other low-fertility countries, particularly people’s lack of confidence in their economic future. But there are several other factors. Day care centers usually close at 1 p.m., a burden on the growing number of two-earner families. Social attitudes tend to disfavor leaving one’s child in the care of someone else for the entire day. Mothers who do leave their children all day are often considered to be “raven mothers” (Rabenmutter) because a raven abandons her young at an early age. But this attitude may be slowly changing with growing acknowledgment of a birth rate crisis. Some day care centers now sport Ganztags! signs (all-day day care). The government took little direct action until well after 2000, despite growing concern over the diminished number of young people and its effect on supporting pension programs and virtually free health care, particularly for the elderly.

To try to increase the birth rate, the government gives 184 euros monthly for the first and second child, 190 euros for the third, and 215 for the fourth until each child turns 18 (or 25 if still pursuing an education). Maternity leave spans 14 weeks, six weeks prior to the birth and eight weeks afterward—with a minimum benefit paid of 13 euros per day. Finally, a monthly minimum of 300 euros is allocated for care of a newborn but can rise to 1,800 euros or 67 percent of one’s prior salary. This is paid for 14 months with the stipulation that one parent must use the benefit for two months, a feature that ensures that fathers will take part in child care. The additional expense has put a strain on the national budget and has had little effect on birth rates. But only a few countries in the industrialized world have seen significant increases in birth rates from these kinds of family benefits—notably Russia and the Canadian province of Quebec.

Challenges

To date, efforts to raise fertility in Germany have not been successful. In two Eurobarometer surveys, respondents were asked about their “personal ideal” number of children. In 2001, German women ages 15 to 24 said 1.8 children; in 2006, they said 2.0. In contrast, in France the answer was 2.6 for both survey years. Answers to questions on ideal numbers of children, however, are nearly always much higher than fertility actually achieved in developed countries. In the 2001 survey, among German women ages 18 to 34, nearly 17 percent gave “none” as their ideal and 9 percent said “one,” percentages far higher than other EU countries.

Projections from the National Statistical Office assume that, if there is a rise in fertility, it will be quite modest. With an increase to a fertility rate of 1.6 children and annual net immigration of 200,000, Germany’s population would decrease to 74.5 million in 2060 with 31 percent of the population ages 65 and older. Should fertility remain at 1.4 children and immigration amount to 100,000 per year, the 2060 population would decline to 64.7 million, with 34 percent ages 65 and over. Given the stable trend in fertility over the last 35 years and the lack of success of pronatalist programs, population decline and continued aging appear to describe the country’s future quite well.

Previous:

World Population Growing at Record Speed

Phase 1: Uganda: At the Beginning of the Demographic Transition

Phase 2: Guatemala: Beyond the Early Phase of the Demographic Transition

Phase 3: India: On the Path to Replacement-Level Fertility?

Population Bulletins

View All

Global Aging and the Demographic Divide

This article was originally printed in the Public Policy & Aging Report 17, no. 4 (2007).

(April 2008) In the latter half of the last century, the world’s developed nations completed a long process of demographic transition.1 The field of demography describes this demographic transition as a shift from a period of high mortality, short lives, and large families to one with a longer life expectancy and far fewer children.

This transformation took many centuries in Europe and North America as people moved from farms to cities; basic public health measures steadily reduced the risk of contagious disease; and modern medicine prolonged lives to unprecedented lengths. In developing countries, this demographic transition is certainly underway, though these countries vary widely at their places along the spectrum.

Very low birth rates and the resultant population decrease have received considerable media attention, particularly in Europe and parts of eastern Asia. In the past, when demographers projected national and global populations, the projections commonly assumed that birth rates would decline worldwide but only to the “two-child” family, i.e., two children per woman or per couple on average. An assumption that fertility would fall below this rate would have some unpleasant consequences: a decrease in population size and a population top-heavy with retired seniors who would depend upon the social taxes paid by a dwindling number of younger workers. While it may not have been desirable to project such a gloomy scenario in the past, this is exactly what has transpired in many countries.

Today, the global population has come to what we may call a great “demographic divide.” Very low birth rates have inflicted long-lasting alterations upon the age structure of Europe, although the effect is more severe in some countries than in others. A real battle has ensued over retirement age. Governments know that the age at which public pensions can be collected should be raised, even though the idea meets frequent public resistance. Labor force shortages are recognized, particularly among less desirable service occupations, but there is little agreement on how to resolve them.

Immigration is one obvious solution and there is no shortage of those willing to migrate to help solve it. But that solution often leads to a fear of losing national identity. Anxiety over immigration is different in Europe than in North America since most Europeans do not see themselves living in multicultural societies. Japan, in particular, is especially resistant to an immigration solution. Debates over how to solve labor force issues range from providing remedial training where it may be needed, to greater inclusion of women in the workforce, to simply raising the birth rate. In Germany, the rallying cry of those opposed to the immigration solution has been “Kinder statt Inder” (Children instead of Indians).

Figure 1 presents the demographic divide with dramatic clarity. It is apparent that, for all practical purposes, all of world population growth is taking place in the developing countries, and it is likely to continue to do so. Of this, there is little doubt. Today, there are about 1.2 billion people living in developed countries and 5.4 in developing countries. By 2050, the number living in developed countries will not have changed but there will be 8 billion in the developing countries.2 In the developed countries, the 1.2 billion number remains constant only because population growth in the United States offsets decreases in Europe and Japan.

Figure 1

World Population Growth, 1950-2050

Source: United Nations, World Population Prospects as Assessed in 2008.

Source: United Nations, World Population Prospects as Assessed in 2008.

The projections require at least one major caveat. The projected figure for 2050 makes the very important assumption that birth rates in developing countries will continue to decline quite smoothly where they already are declining or will soon begin to decline where they have not as yet begun to do so. This is quite a significant presupposition. In recent years, survey data from quite a few African countries have shown that declines in birth rates have slowed down after declining from very high levels, such as seven or eight children per woman.

Alternative projections of the United Nations suggest that developing countries could surpass 9 billion. Trends in fertility play a key role in projections. The eventual population size of developing countries will be affected by a number of issues, such as what family size will emerge as the standard in the developing world—will it be two children per family? More or less? Further, if fertility declines more slowly in some regions than in others, projections will have to be adjusted. In fact, such adjustments take place all the time, a necessary practice of any forecasting procedure. At least as significant is what Figure 1 does not show. It is not, of course, simply overall population size that matters, but age structure.

Figure 2 illustrates the population “pyramid” of Germany in 2005. Such histograms are called pyramids since they are typically wider at the bottom than at the top, as seen in many pyramids representing developed countries. But Germany’s pyramid has quite a different look. At current rates, women in Germany would average only 1.3 children in their lifetime. The effect of low fertility is plainly evident in the pyramid. The youngest age group, 0-4 at the bottom of the pyramid, is exactly half of the age group 40-44, the largest group. In many low fertility countries, low birth rates are not a recent phenomenon. In Germany, the rather narrow bars beginning with those born 30 to 34 years ago show this clearly. This is a permanent alteration to the country’s age structure that cannot be undone without, of course, increased immigration.

Figure 2

Germany by Age and Sex, 2005

Source: United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision.

Low fertility countries like Germany are defined by having a total fertility rate (TFR) below 2 children per woman.3 Despite comparatively high fertility and substantial immigration, the United States, with a TFR of 2.05, will also experience unprecedented aging. The TFR is now the most closely watched demographic rate in low fertility countries as it takes the “pulse” of the birth rate each year. A TFR of about 2.1 children is often called the “replacement rate” since, at that rate, couples simply replace themselves, eventually leading to a stationary population size. Below that rate, deaths will at some point exceed births and a population will decline in size.

While the media have paid a lot of attention to “old” Europe, the fertility situation in this region and throughout Asia has considerable variation, and it is important to remain aware of its differences and trends. Generally, countries that have been “family friendly”—in terms of child payments, provision of daycare, and maternity/paternity leave—have fared better than others. This can be seen in the TFRs of northern Europe and France, where fertility is close to two children per woman and has been modestly increasing in recent years.

Confounding the analysis of TFRs are the effects of fluctuations in national economies and employment prospects, and the tendency for childbearing to shift to older ages. A loss of confidence in the economy often results in a reduction or delay in childbearing. When childbearing is delayed, the TFR will decline to a degree and then recover when couples decide “it’s now or never.” Fertility in Sweden has shown substantial swings often attributed to economic effects, rising to 2.1 children around 1990, falling to 1.6 in the mid-1990s and now rising once again. Dramatic fluctuations of that magnitude are not typical, however.

In Europe and eastern Asia, fertility remains at what is seen as catastrophically low levels, and countries have been slow to react. While such attitudes are now changing rapidly, any increases in the TFR are few and far between and modest at best. Reasons for low fertility can vary quite a bit across countries and some examples of those differences are useful.

In Germany, it remains socially unacceptable to leave one’s child in all-day daycare and most kindergartens close at 1:00 PM, placing a significant burden on parents. The new administration of Chancellor Angela Merkel has placed great emphasis on providing a more accommodating climate for couples with young children, by increasing child payments and, ultimately, providing day-long childcare. In so doing, Germany’s policies may become more in line with family-friendly France whose support of young families is legendary.

In Italy, childbearing outside of formal marriage is generally not socially acceptable, as it is in Sweden where over half of births are outside marriage. Young people in Italy face a tight job market, and as a result, marriage and childbearing can be greatly delayed. In Eastern Europe, birth rates had been comparatively high prior to the breakup of the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact. After that event, collapsing economies brought the birth rate down with them quite rapidly; this region now has Europe’s lowest fertility. In Japan, raising children is not only perceived as expensive, but most family duties fall to wives as husbands often work long hours and participate very little in domestic chores.

The future course of TFR will determine the level to which countries will experience societal aging. What might we expect? The degree to which generous family policies affect birth rates is debatable, but the simple fact remains that countries with such policies have the highest TFRs. There is potential for change in low fertility rates, reflected in the results of the Eurobarometer surveys conducted by the European Commission. In the 15 countries surveyed in 2006, the “personal ideal family size” was above two children in all countries except Austria.4 This ranged from 3.0 among women in Ireland to 1.66 among men in Austria. Interestingly, the current TFR in Ireland is only 1.6.

Overall, European males had a somewhat lower ideal family size than females. One very noticeable change between the 2006 survey and the Eurobarometer conducted in 2001 was the large increase in ideal family size among males in Germany. In 2001, German males ages 15-24 gave 1.42 children as their ideal but that increased to 2.17 in 2006—higher than females of the same age. This increase occurred across all age groups. There is no particular explanation for this change other than the fact that recent media in Germany have given attention to the country’s low male fertility aspirations.

Could the results of the Eurobarometer point to a future increase in European fertility? The “ideal” family size survey can be a poor indicator of future fertility if sufficient family support programs are not available. Overall, in the 15 countries surveyed, males gave 2.25 as their ideal while females gave 2.38. In family-friendly France, males gave 2.45 children and females 2.59 while the current TFR is 1.98. Evidence like this suggests that few couples are likely to reach their stated ideal number of children even with significant public support. This, in turn, suggests that a robust economy combined with adequate family policies could well increase birth rates, but that very significant increases (above two children on average) are unlikely.

All developed countries, regardless of their current fertility level, have one thing in common: substantial future aging. Without a very dramatic increase in fertility—and a rapid one—unprecedented aging is now assured. The only question remaining is a matter of degree. The population pyramid of Japan for 2055 in Figure 3 provides a striking illustrative example of the consequences of low fertility over the long term. This pyramid results from the middle series official projection of the Japanese government; middle series projections are often treated as “most likely” scenarios and are used for planning purposes. Alternative projections would result in a less pessimistic scenario but would still show very substantial aging.

Figure 3

Japan by Age and Sex, 2055

Source: National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.

One of the most striking features of the pyramid is the very high proportion of the “old old,” which we can define here as those age 80 years and over. In 2055, 19 percent of Japan’s population will fall in that category, including 634,000 centenarians. At the same time, the country’s population size will have shrunk from 128 million today to 90 million. The consequences for the country’s pension and health care systems are without precedent. Today, the state of Japan’s birth rate is being treated as a national crisis, but it may safely be said that it is too little, too late. If effective steps are taken, some couples would undoubtedly be motivated to have more children, but it will take much more than that to change the picture in Figure 3 in a truly significant way.

Although future changes in fertility will likely have the most noteworthy effect on changing the pyramid, past and future increases in life expectancy have had and will have their own effect, particularly in the numbers of the old old. Currently, life expectancy at birth in Japan stands at 79 years for males and 86 years for females. These are without historic precedent and continue to rise as the projected pyramid in Figure 3 also assumes. Japan’s life tables for the years 1921-1925 show that life expectancy at age 75 stood at 5.3 years for males and 6.2 years for females. In 1995, those figures were 9.8 and 12.9 years, respectively. As high as these life expectancies are, they are still increasing. In 2004, life expectancy at age 75 was 11.2 years for males and 14.9 for females. A woman who survived to age 75 could expect to live to age 90.

The developed nations set records for high levels of societal aging, but what about developing countries? Given the higher levels of fertility at present, it is obvious that aging will be less of a factor in poorer countries compared to wealthier ones. But aging will take place, and in some cases, rival levels seen in the developed world.

By 2050, the developing regions of Asia and Latin America will find that their populations age 65 and above, as a percentage of the working age population (ages 15-64), will be roughly equivalent to what is found in developed countries today. This will certainly be a new challenge but also one for which there is time to prepare.

One significant difference in the projected age structures between developed and developing countries is that fertility in developing countries is not projected to fall to some of the very low levels observed in Europe—or at least today’s projections do not make that assumption. It should be kept in mind, however, that several developing countries often referred to as “newly industrialized countries” (NICs), such as South Korea and Taiwan, saw such a decline in their TFRs that they now have the lowest fertility rates in the world.

In Africa, fertility today remains at quite a high level and, as mentioned earlier, does not appear to be declining very rapidly. Further, life expectancy remains low-barely 50 years in sub-Saharan Africa. For these reasons, Africa’s population will remain relatively young for the first half of this century and has yet to show the effects of rising life expectancy. In Asia, the outlook is much more diverse. China, which accounts for one-third of Asia’s population, today has a TFR of only 1.5, due to its government-enforced policy. In India, fertility decline has been much more gradual and remains modestly high at about 4 children per woman in some of its most populous states. Finally, Latin America’s demographics have come to resemble that of its northern neighbors, and that region can expect a somewhat similar aging pattern.

In summary, for the foreseeable next few decades at least, extreme societal aging will likely be found only in Europe and a few Asian countries. At the same time, the developing world will remain comparatively young, deepening the demographic divide. Developed countries with very low fertility face important choices if they are to avoid a collapse of pension systems and a heavy burden of caring for never-before-seen proportions of elderly citizens.

For many countries, increases in birth rates will not be sufficient because they will happen too late, and few expect such increases to be significant. This clearly implies that the acceptability of immigration as a solution will have to increase in order to solve labor force problems and increase the number of workers paying social taxes. Yet, out of all possible solutions, immigration has the least appeal. In the 2006 Eurobarometer survey, the three most commonly cited solutions to labor shortages were, in order: encouraging non-working women to participate in the labor market, encouraging part time workers to become full time, and raising the birth rate. Similarly, the three least popular solutions were the following: encouraging immigration from outside the European Union, raising the retirement age, and increasing weekly working hours.

Demographically, the world has reached an unusually challenging point in its history. Today, the prospect is for a growing developing world population and a shift of economic influence away from the developed world, the former colonial powers, and into the developing world over which they once held domain. While some aspects of this shift are clear, others are less easy to predict. Many countries will of necessity become more ethnically diverse, particularly among their younger age groups. It will be a different world.

Carl Haub is a senior demographer and Conrad Taeuber Chair of Population Information at the Population Reference Bureau.

References

- The United Nations defines “more developed” countries as Europe (including Russia), North America (not including Mexico), along with Australia, Japan, and New Zealand. All other regions and countries are “less developed.” In this article, “developed” countries also comprise some emergent economies with low birth rates, such as South Korea and Taiwan and even China.

- Carl Haub, 2007 World Population Data Sheet (Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau, 2007).

- The total fertility rate is the average number of children a woman would bear if the rate of childbearing of a particular year remained constant throughout her lifetime.

- European Commission, “Childbearing Preferences and Family Issues in Europe,” Eurobarometer 65.1 (2006).

Poverty in the United States and Other Western Countries

(May 2002) It is difficult to compare poverty levels in different countries. Countries not only have different currencies, they have different family income levels, consumption patterns, prices for goods and services (which affect purchasing power), spending patterns, and family and demographic characteristics. Different countries also adopt very different criteria for setting absolute income thresholds that define poverty. As a result, most cross-national studies use relative measures of poverty as a basis for comparison.

A recent study by Timothy Smeeding, Lee Rainwater, and Gary Burtless showed striking differences in western countries’ rates of relative poverty, which they defined as 50 percent of the median adjusted disposable personal income (ADIN) for persons (adjusted for family size). They also measured deep poverty, defined as 40 percent of the median ADIN. Using data from the Luxembourg Income Study, the researchers showed that the United States has the highest relative poverty (and deep poverty) rates among those countries observed (see figure).

Relative Poverty in Selected Industrialized Countries, 1990s

Source: Luxemborg Income Study, “Key Figures: Relative Poverty Rates”

(www.lisproject.org/keyfigures/povertytable.htm, accessed April 2, 2002).

Reference

Timothy Smeeding et al., “United States Poverty in a Cross-National Context,” Focus 21, no. 3 (2001): 50-54.

Most European Women Use Contraceptives

Date

April 1, 2001

Author

PRB

(April 2001) Europe has the lowest fertility rates in the world. In 2000, the average for the region was 1.4 children per couple, and it ranged from 1.1 children in Bulgaria and the Czech Republic to 2.2 children in Albania.

Social scientists posit a number of explanations for Europeans’ apparent reluctance to have children. Many point to the rising costs of raising children — not just higher costs of living, but also the personal costs to parents of deferred professional advancement and individual fulfillment. Another explanation focuses on related changes in social expectations about marriage and family formation: Young Europeans may not feel the same social pressure to get married and have children as did their parents and grandparents.

Europe’s low fertility has also been linked to the so-called “contraceptive revolution.” There is a common assumption that access to effective contraception is universal in Europe and that European women can successfully control if and when they get pregnant. Until recently, however, there was little empirical evidence about contraceptive use among European women. In the 1990s, a series of national surveys revealed new information about the level of contraceptive use and the most popular methods in various countries. The surveys also show that European women still have surprise pregnancies, despite the easy availability and high contraceptive use rate. (See Box below.)

The vast majority of European women of childbearing age use contraception — and Europeans are more likely than Americans to be practicing birth control. In most European countries, more than four out of five women of childbearing age who were married or in a marriage-like relationship were using a contraceptive method at the time of the survey. The use rates ranged from 92 percent in Hungary in 1993, to 66 percent in Lithuania in 1995 (see Table 1). A 1995 survey in the United States showed that three-quarters (75 percent) of currently married American women ages 15 to 44 were using a contraceptive method; 69 percent of formerly married American women were using a method.

Table 1

Contraceptive Use in Selected European Countries, 1990

| Country/ Year of survey | Percent of women in union using contraception |

|---|---|

| Austria, 1996 | 67.9 |

| Belgium, 1992 | 84.2 |

| Finland, 1990 | 84.0 |

| France, 1994 | 89.9 |

| Germany, 1992 | 84.8 |

| Hungary, 1993 | 91.8 |

| Latvia, 1995 | 84.9 |

| Lithuania, 1995 | 65.9 |

| Norway, 1989 | 80.3 |

| Poland, 1991 | 75.7 |

| Slovenia, 1995 | 84.4 |

| Spain, 1995 | 87.2 |

| Canada, 1995 | 80.2 |

| United States*, 1995 | 76.4 |

* Currently married women ages 15 to 44. Note: The percentage is based on a sample of women of reproductive age who were in union and therefore exposed to the risk of pregnancy. The ages of respondents varied by country. Most surveys included women 20 to 45; some surveys also included slightly younger and older women.

Sources: Author’s calculations of data from the Fertility and Family Surveys; and J. Abma, A. Chandra, W. Mosher, L. Peterson, and L. Piccinino, “Fertility, Family Planning, and Women’s Health: New Data from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth,” Vital and Health Statistics Series 23, no. 19 (Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 1997): Table 42.

The nearly universal use of contraception in Europe today is a phenomenon that appeared in the past three decades. Only one-third of European women born in the 1940s and 1950s used contraception the first time they had sex, for example, while more than two-thirds of women born in the 1970s used contraception the “first time.”

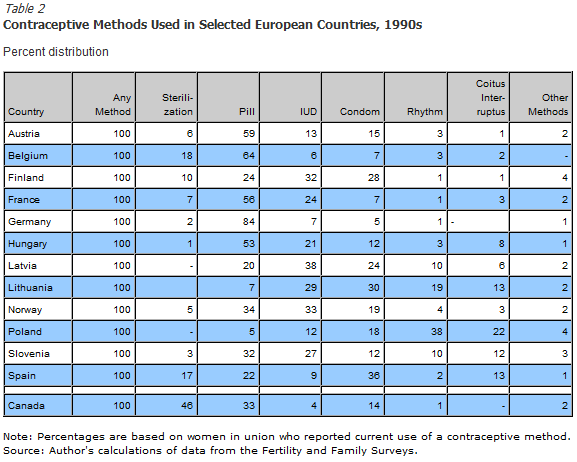

Most European women rely on highly effective contraceptive methods. Oral contraceptives are the most popular form of birth control; the pill is particularly dominant in Germany where it accounts for 84 percent of contraceptive use (see Table 2). Female sterilization, which rivals the pill as the top method in the United States, is not as popular in Europe. Sterilization was important only in Belgium, Spain, and Finland, where it accounted for 10 percent to 18 percent of use.

Surprisingly, traditional methods that have a relatively high failure rate are still widely used, especially in Spain and Eastern Europe. In Poland, more than one-third of women in a marital union reported using the rhythm method, while more than one-fifth said they used withdrawal. Rhythm (or periodic abstinence) and withdrawal (“coitus interruptus”) are the only forms of birth control condoned for married couples by the Catholic Church. This religious sanction might explain the higher use rates for these methods in countries like Poland and Lithuania that have large Catholic populations. Another barrier to the use of the pill or other “supply” methods in former Soviet countries, including Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, was that the importation of contraceptives was often limited and many women did not have a reliable source of supply.

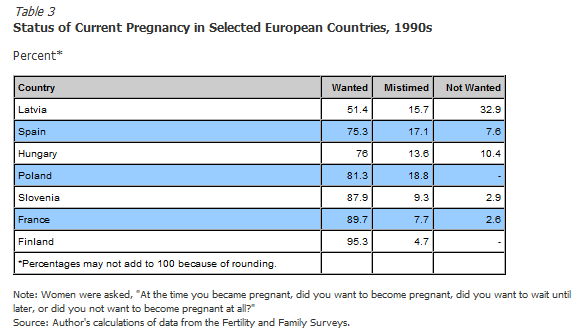

The efficiency of contraceptive methods used vary from country to country, in part reflecting the reliability of supply and consistency of use. Contraceptive failure is starkly reflected in measures of unwanted pregnancy. Nearly one-half of Latvian women and more than one-fifth of Hungarian and Spanish women pregnant at the time of the survey said they had not wanted their current pregnancy, or had wanted it at a later time (see Table 3). In France this share was 10 percent; in Finland, it was only 5 percent. In a 1995 survey in the United States, by comparison, about 9 percent of pregnancies were unwanted at the time of conception. A much larger share of pregnancies (21 percent) were “mistimed,” according to U.S. women interviewed.

How can European women avoid unwanted pregnancies? Better information and education on reproductive health could help. Despite high levels of formal education, some women still have gaps in their knowledge about when they are fertile or how to use contraceptives effectively.

Reducing unwanted pregnancies would prevent many abortions, which many people consider a laudable goal — abortion is quite prevalent in some Eastern European countries. Eliminating unwanted pregnancies would also reduce fertility, however, which is not a popular outcome. Most Europeans would not welcome lower fertility rates.

Ralf Ulrich is president of Eridion, GmbH, based in Germany.

Box

Collecting Information on Contraceptive Use in Europe

Until recently, there has been more information on contraceptive use and family planning in less developed countries in Asia, Latin America, and Africa than there has been in Europe. There have been several series of national surveys administered in less developed countries since the 1970s, fueled by the apparently urgent need for information about childbearing and family planning in countries where women had five to six children, on average, and where population growth was outstripping economic growth. The most recent and extensive effort is the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) project, which involves more than 140 surveys in nearly 70 countries. But there has been less urgency about family planning behavior in Europe, where women appeared to have control over their reproductive lives and fertility was low. Only a few countries in the region conducted national surveys before the 1990s.

In the 1990s, a series of fertility surveys known as the Fertility and Family Surveys (FFS) were conducted in 24 more developed countries, primarily in Europe. The national surveys of 1,700 to 6,000 women (depending on the country) are an important source of information about contemporary patterns in the use of contraception in Europe. The questionnaires covered a broad range of problems related to fertility and family formation; many of the surveys also included a questionnaire for men. The minimum ages of respondents were not uniform, however. In most surveys, the ages of respondents ranged from 15 to 24 at the lower end, and from 40 to 49 at the upper end.

The design of the FFS benefited from the experiences with the DHS in less developed countries. Implementing the FFS questionnaires showed, however, that it was much more difficult to use standardized questionnaire modules in Europe than in the DHS countries. Consequently, FFS survey data on contraceptive use and other variables are less comparable than DHS data sets. Published individual country reports differ substantially in the way contraceptive prevalence is computed, but they provide a benchmark for further research into childbearing and family planning in Europe.

">

">