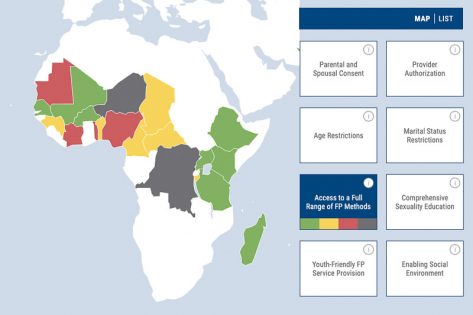

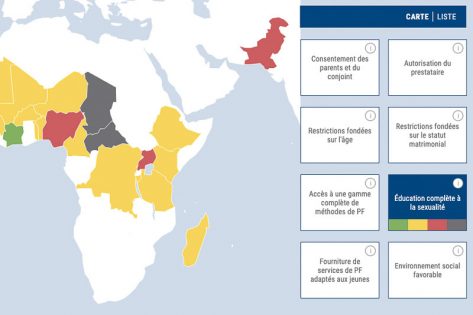

To address this evidence gap, PRB conducted research and analysis to identify the most effective policies and program interventions to promote uptake of contraception among youth, defined as people between ages 15 and 24. This research has been compiled into the Youth Family Planning Policy Scorecard to evaluate and compare the favorability of current national policy and program environments.

Based on a review of existing evidence and expert consultations, the following indicators were selected as evidence-based interventions for inclusion in the Scorecard:

- Policy barriers related to consent (parental, spousal, or service provider); age; and marital status.

- Policies supporting access to a full range of family planning methods.

- Policies related to comprehensive sexuality education.

- Policies supporting/inhibiting youth-friendly family planning service provision.

- Policies related to an enabling social environment for youth family planning services.

The Scorecard can be used by governments, donors, and advocates to evaluate a country’s youth family planning policy environment, set policy priorities, guide future commitments, and compare policy environments across countries.

The March 2022 edition of the Scorecard includes data for 28 countries: Bangladesh, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Guinea, Haiti, India, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Nepal, Niger, Nigeria, the Philippines, Senegal, Sindh (Pakistan), Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, and Zambia.

">

">

">

">

">

">