South Korea's Demographic Dividend

(November 2012) The countries known as the “Asian Tigers” are good examples of the advantages to be gained when changes in fertility can be a springboard for economic growth. (The Asian Tiger countries are Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand.)

South Korea made a rapid transition from high to low fertility, while at the same time experiencing an annual growth in per capita gross domestic product of 6.7 percent between 1960 and 1990. South Korea’s success was the result of addressing population issues, while also investing in reproductive health programs, education, and economic policies to create infrastructure and manufacturing.

The demographic dividend is the accelerated economic growth that begins with a decline in a country’s mortality and fertility and the subsequent change in the age structure of the population. With fewer births each year, a country’s young dependent population grows smaller in relation to the working-age population. With fewer people to support, a country has a window of opportunity for rapid economic growth if the right social and economic policies are developed and investments are made.

A Quick Fertility Transition

The three population pyramids illustrate how quickly the fertility transition in South Korea took place. Between 1950 and 1975, fertility began to drop from 5.4 children per woman to 2.9, indicating the transition was well underway. However, by 2005, the pyramid indicates that South Korea’s age structure was that of a mature population, with fertility dropping to 1.2 children per woman.

Figure 1

South Korea’s Age and Sex Structure, 1950

<

<

Source: United Nations Population Division, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision (New York: United Nations, 2011).

Figure 2

South Korea’s Age and Sex Structure, 1975

Source: United Nations Population Division, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision (New York: United Nations, 2011).

Figure 3

South Korea’s Age and Sex Structure, 2005

Source: United Nations Population Division, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision (New York: United Nations, 2011).

Behind this transition was an aggressive population policy, widely implemented throughout the public and private sectors. Although the government invested in health centers to provide a range of services including family planning, use of the centers was relatively low. However, field workers visited homes and provided family planning information and methods—a more effective strategy for reaching women than clinic-based services. The family planning program encouraged acceptance of family planning and invested in training providers, information and education, and contraceptive supplies. The government set a target of 45 percent of married couples using family planning. The creation of mothers’ clubs also contributed to the implementation of the policy in 19,000 villages. A contributing factor to reducing fertility was that people saw that having fewer children improved family life.

Shifting the Education Strategy

To set the course for the demographic dividend, the government also focused on education. Between the 1950s and 1960s, South Korea’s education strategy shifted from one of compulsory primary education, which served only about 54 percent of school-age children, to a “production-oriented” education that would provide people with the knowledge and skills they needed to achieve economic development. The shift in focus and increased commitment to education contributed to 97 percent of school-age children attending school in 1990. Relatively fewer children attending school, more disposable income at the household level, and a sustained investment in education contributed to a better-educated population, which in turn contributed to rapid economic development through a skilled labor force.

Comprehensive Economic Plans

At the same time, South Korea’s economic plans were comprehensive and evolved over many years. Following the Korean War, South Korea’s economy was based on farming and fishing—and neither industry was sufficiently strong. Normalizing relations with Japan led to infusions of investment capital that strengthened the fledgling agricultural and fishing industries, as well as manufacturing and shipping. The South Korean government also addressed unemployment through a rural construction program that provided minimum wages for workers involved in the construction of infrastructure, including dams and roads, as well as erosion control and reforestation. This effort focused on creating a “self-help” attitude that contributed to both the development of a national infrastructure and economic growth. The war in Vietnam reinforced manufacturing opportunities, as well as opportunities for South Korean firms to win infrastructure projects in Vietnam. Over time, South Korea also established chemical, iron, and steel industries that contributed to improvements in balance of trade. South Korea was rapidly increasing the capital (investment) per workers at more than 8 percent per year—a trend that lasted from 1965 to 1991.

Well-Timed Changes Led to Demographic Dividend

South Korea’s rapid demographic transition was a by-product of two well-timed changes. On the one hand, deliberate population policies contributed to slower population growth, which helped create an age structure that facilitated the beginning of South Korea’s demographic dividend. At the same time, rapid socioeconomic change affected savings, investment, and the roles of women. The foresight to develop and implement such policies, plus the right economic and social conditions, enabled South Korea to experience a demographic dividend that has since become the goal of other countries.

James N. Gribble is vice president of International Programs at the Population Reference Bureau.

References

- Andrew Mason, “Population and the Asian Economic Miracle,” Asian-Pacific Population and Policy (October 1997).

- In-Joung Whang, “Integration and Coordination of Population Polices in Korea,” Asian Survey 14, no. 11 (1974): 985-99; Princeton N. Lyman, “Economic Development in South Korea: Prospects and Problems,” Asian Survey 6, no. 7 (1966): 381-88; and T.C. Rhee, “South Korea’s Economic Development and its Social-Political Impact,” Asian Survey 13, no. 7 (1973): 677-90.

- United Nations Population Division, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision (New York: United Nations, 2011).

- Whang, “Integration and Coordination of Population Policies in Korea.”

- Whang, “Integration and Coordination of Population Policies in Korea”; and Mason, “Population and the Asian Economic Miracle.”

- Whang, “Integration and Coordination of Population Policies in Korea”; and Rhee, “South Korea’s Economic Development and its Social-Political Impact.”

- Rhee, “South Korea’s Economic Development and Its Social-Political Impact.”

- Mason, “Population and the Asian Economic Miracle.”

Norway and South Korea Owned the Demographic Podium at the 2010 Winter Olympics

(April 2010) At the recent Vancouver Winter Olympics, much was written about Canada’s “Own the Podium” initiative to lead the medal standings. That didn’t quite happen, as the host country’s neighbor, the United States, won the largest number of medals with 37, including nine gold, setting a Winter Games record. Yet with 14 gold medals (out of 26 overall), Canada set a record of its own—the most golds ever won by a country in a single Winter Olympics. Other countries that did well in the medal count were perennial winter-sports powers: Germany (30 medals, 10 gold) and Norway (23 medals, nine gold). All told, a record-tying 26 of the 82 participating nations earned at least one medal in Vancouver.

But a demographic examination of the medal standings shows that neither the Americans nor the Canadians owned the podium. PRB’s Crude Medal Rate (CMR), like the crude birth and death rate, considers a country’s population size. Calculating this measure involves dividing the total number of Olympic medals a country won in Vancouver by its total population, then multiplying the result by 1 million. As was the case in the previous three Winter Olympics, Norway was the big winner under this measure. The 23 medals the Scandinavian nation of 4.8 million residents won in 2010 translate into a rate of 4.8 medals per million (see Table 1). This was more than twice the CMR of 1.9 for second-place Austria, which likewise benefited both from its high overall medal total (16, including four gold) and its relatively small population of 8.4 million.

Table 1

Crude Medal Rate, 2010 Winter Olympics

(Medals per 1 million population, countries with at least one medal in the 2010 Vancouver Olympics)

| Country |

Crude Medal Rate |

Number of Medals | 2009 Population (millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Norway | 4.8 | 23 | 4.8 |

| Austria | 1.9 | 16 | 8.4 |

| Slovenia | 1.5 | 3 | 2.0 |

| Sweden | 1.2 | 11 | 9.3 |

| Switzerland | 1.2 | 9 | 7.8 |

Sources: Vancouver Olympic Committee, official website of Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics, accessed at www.vancouver2010.com, on March 3, 2010; and PRB, 2009 World Population Data Sheet.

Indeed, countries with small populations benefit under the CMR. Slovenia, for example, won only three medals in Vancouver (two silvers in alpine skiing and a bronze in cross-country skiing), but its population of 2 million helped produce a CMR of 1.5 medals per million, good enough for third place on this measure. By contrast, the larger populations of both Canada (33.7 million) and especially the United States (306.8 million) yield CMRs of 0.8 and 0.1, respectively, putting both countries well behind Norway.

The two North American nations fare better under a second demographic measure, the General Olympic Medal Rate (GOMR). Conceptually similar to the general fertility rate (which measures the number of births per 1,000 women of childbearing age), this measure accounts for the actual number of athletes a nation sent to Vancouver—that is, the actual “population” eligible to win a medal. The 214 athletes the United States sent to the Olympics produced a GOMR of 17.3 medals for every 100 athletes—good enough to rank it sixth on this measure. The host Canadians, who had 205 participants in Vancouver, placed eighth with a GOMR of 12.7. CMR leader Norway ranked near the top on this measure as well; its GOMR of 23 medals per 100 participants put it in third place (see Table 2). But the podium “owner” on this measure was South Korea. The 46 South Korean athletes who competed in Vancouver won 14 medals (including six gold), producing a GOMR of 30.4 per 100 athletes. The Netherlands, who won eight medals despite sending just 34 athletes to Vancouver, ranked second at 23.5.

Table 2

General Olympic Medal Rate, 2010 Winter Olympics

(Medals per 100 athletes, countries with at least one medal in the 2010 Vancouver Olympics)

| General Olympic Medal Rate | Number of Medals | Number of Participating Athletes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| South Korea | 30.4 | 14 | 46 |

| Netherlands | 23.5 | 8 | 34 |

| Norway | 23.0 | 16 | 79 |

| Austria | 20.3 | 16 | 79 |

| Germany | 19.7 | 30 | 152 |

Source: Vancouver Olympic Committee, official website of Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics, accessed at www.vancouver2010.com, on March 3, 2010.

Of course, neither the CMR nor the GOMR accounts for all the complexities of the games. For example, the Olympics contain a mixture of individual and team events, and not all nations competed in every sport. And some athletes such as skiers and speed skaters competed—and won medals—in multiple events. Finally, regardless of the measure used, any talk about which nation really “owned the podium” obscures the fact that the athletes, not the countries they represent, are the ultimate Olympic champions.

Kelvin Pollard is a senior demographer at the Population Reference Bureau.

Did South Korea's Population Policy Work Too Well?

Date

March 27, 2010

Author

Carl Haub

Demographer Emeritus

Many developing countries adopted policies to slow population growth in the latter half of the 20th century in response to population growth rates that had risen to three or more times greater than those ever observed in industrialized countries. Developing countries experienced rapid declines in their death rates after 1950 with no offsetting decline in birth rates, as had previously occurred in Europe and North America. Some policies had great success, some partial success, and others little or none. South Korea serves as one example of a former developing country whose program to lower the birth rate had an unexpected result: Fertility so far below the “two-child” replacement level that severe population aging and decline in population size is now a very real prospect. South Korea was also one of the few developing countries to have initiated a population policy to lower the birth rate during the period of concern in the 1960s and 1970s over the population “explosion”; and to have its birth rate subsequently fall to world record low levels.

South Korea is far from alone in experiencing very low fertility. About 35 countries worldwide have total fertility rates (TFRs) of 1.5 children or below. There has been speculation that such a development may signal a longer-term change in childbearing in industrialized societies than was once thought. Demographer Wolfgang Lutz and colleagues have suggested that decreases in birth rates may constitute a real change in societal norms, something he labels a type of “low-fertility trap.”1

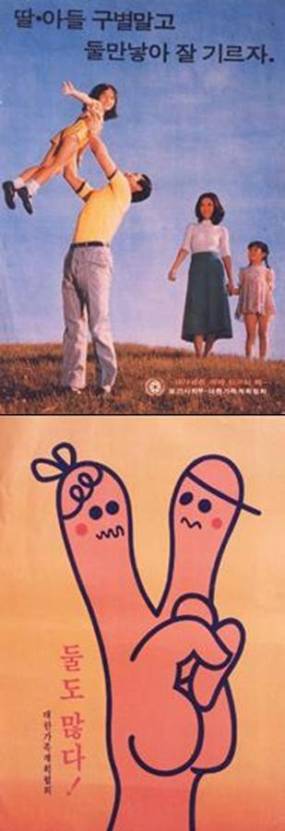

Smaller Families and Economic Development in the 1960s and 1970s

Following the Korean War in the early 1950s, South Korea’s population remained primarily rural and agricultural. Its TFR exceeded six children per woman. In 1962, South Korea began its national family planning campaign to reduce women’s unwanted births through a program of information, basic maternal and child health services, and the provision of family planning supplies and services. The program was seen as essential if the goals of economic growth and modernization were to be achieved. Overall, the public responded well to the idea of a “small and prosperous family.” By 1970, the TFR had fallen to 4.5 against a background of rapid industrialization and the waning of the country’s largely agrarian character. A 1974 poster (see figure’s top image) exhorted, “Sons or daughters, let’s have two children and raise them well.” In 1981, the government, buoyed by its success up to that point, set a target of a two-child, “replacement” level fertility by 1988 with a program of economic incentives. There was even some mention of a one-child family: “Even two children per family are too many for our crowded country” (see bottom image).2 While such a saying may have seemed at least somewhat extreme at the time, it proved to be surprisingly prophetic. The two-child target was met remarkably quickly: The TFR was down to 1.74 by 1984.

South Korean Government Posters Promoted Smaller Families in the 1970s and 1980s

Top image from 1974, bottom image from the 1980s. Source: South Korean government.

Low Fertility, Aging Population, and Pronatalist Policies

Despite the below-replacement TFR, no changes were made in South Korea’s family planning program. Childbearing was almost universal, population continued to grow due to a still youthful age structure, and concerns about the effects of a large population on the country remained. But in 2002, the National Pension Institute reported that the pension fund would soon be wiped out because of a decline in the working age population vis-à-vis the number of retirees. The government also realized that the number of women of childbearing age was declining and that the trend would only accelerate. In addition, the TFR continued to fall below the two-child level. By 2005, the TFR reached a historic global low of 1.08, but it had been well below two children for over 20 years by that point.

In 2005, an advisory committee to South Korea’s president was formed and a law passed to provide the basic legal framework for a new pronatalist policy. This was similar to the approach taken by two other low-fertility countries, Germany and Japan. The Saero-Maji (“new beginning”) Plan for the 2006-2010 period included provisions to provide a more favorable environment for childbearing. The plan had a long list of measures, including tax incentives, priority for the purchase of a new apartment, support for child care including a 30 percent increase in facilities, childcare facilities at work, support for education, and assistance to infertile couples. In June 2006, the government announced the Vision 2020 Plan to raise fertility and prepare for a society with extreme aging. In terms of the TFR, the goal is to raise fertility to 1.6 children per woman (the average for OECD countries) by 2020, a fairly modest rise from the current 1.2 and still well beneath the replacement level.

To what degree can the country’s pronatalist plan succeed? Minja Kim Choe and Nam-Hoon Cho describe factors favoring success of the plan and factors against it. A return to higher fertility levels might be spurred by long-held family traditions, similar to those in other East Asian countries. Patrilineal succession, from father to the eldest son, is a central feature. As a result, marriage has been universal and births outside marriage relatively rare. The parent-child relationship is often valued above that of husband-wife. Great emphasis is placed upon children’s education, and mothers often leave or defer employment to fulfill traditional maternal roles. Young families often live close by with their parents, facilitating child care.

Failure of the policy, on the other hand, could result from a breakdown of those traditional family values. This tendency has been observed in women in South Korea although much less so among parents and among men. The cost of raising children, particularly for education, along with rising employment opportunities for women, have made entering marriage less routine than in the past. In a 2005 survey, 49 percent of single women said that they were reluctant to get married and the percentage of married women who felt a need for children dropped to 65 percent from 90 percent just eight years earlier.3

Although the success of previous policies is cited as a possible factor for meeting the current pronatalist policy objectives, past policies were intended to lower fertility and reduce unwanted births, not raise fertility. Many European countries, along with Japan and Taiwan, are finding that raising very low fertility in changing societies is difficult at best. Korean women do express a desire for two children but so do women in virtually every other industrialized country, with little effect on actual fertility. The costs of a pronatalist policy will also present an obstacle, likely to be even more difficult to accommodate because of the expected slowdown in productivity and economic growth. Notably, the campaign against sex-selective abortion, which had greatly skewed the sex ratio at birth toward boys, was very successful, suggesting that social traditions can adapt to changing times.4

If the goal is to offset the economic effects of low fertility and an aging society, time is of the essence. The population below age 15, which will gradually move up the pyramid and into the childbearing years, has shrunk greatly compared to their parents’ numbers. Even significant increases in the birth rate will have a limited effect on the number of workers per retiree. The consequences of very low past fertility cannot easily be undone. Each year that passes with an extremely low TFR only exacerbates the situation. The number of births for 2009 has just been reported as of March 2010. In 2009, 445,200 births were registered, down from 465,900 in 2008 and 493,200 in 2007. The TFR declined to 1.15 in 2009 from 1.19 in 2008. Marriages declined as well, from 343,600 in 2007 to 309,800 in 2009.

South Korea, along with other industrialized countries with very low birth rates, has come to realize that no single solution is likely to achieve success. A recovery in the Korean birth rate is certainly possible with changes in attitudes on women’s roles by society (and men in particular) along with the establishment of programs and policies by government and businesses. Korea has clearly made the commitment to do just that.

- Wolfgang Lutz, Vegard Skirbekk, and Maria Rita Testa, “The Low Fertility Trap Hypothesis: Forces That May Lead to Further Postponement and Fewer Births in Europe,” Vienna Yearbook of Population Research 2006 (2006): 167-92.

- At 38,000 sq. miles, South Korea, with a 2009 population of 48.7 million, is slightly larger than Portugal (population 10.6 million) and the same size as the U.S. state of Indiana (population 6.4 million).

- Ministry for Health, Welfare, and Family Affairs, The Basic Plan on Aging Society and Population of Korea (Seoul: Ministry for Health, Welfare, and Family Affairs, 2010).

- The preference for sons caused the sex ratio at birth, normally about 105 male babies born to 100 females to begin rising in the early 1980s as the birth rate fell. It peaked in the early 1990s at about 115-117. By 2008, it had virtually returned to normal despite a TFR of only 1.2. This suggests that, if a Korean couple has only one child, it no longer need be a son, quite a significant change in behavior.