Birth Rate Trends in Low-Fertility Countries

Date

March 30, 2011

Author

Focus Area

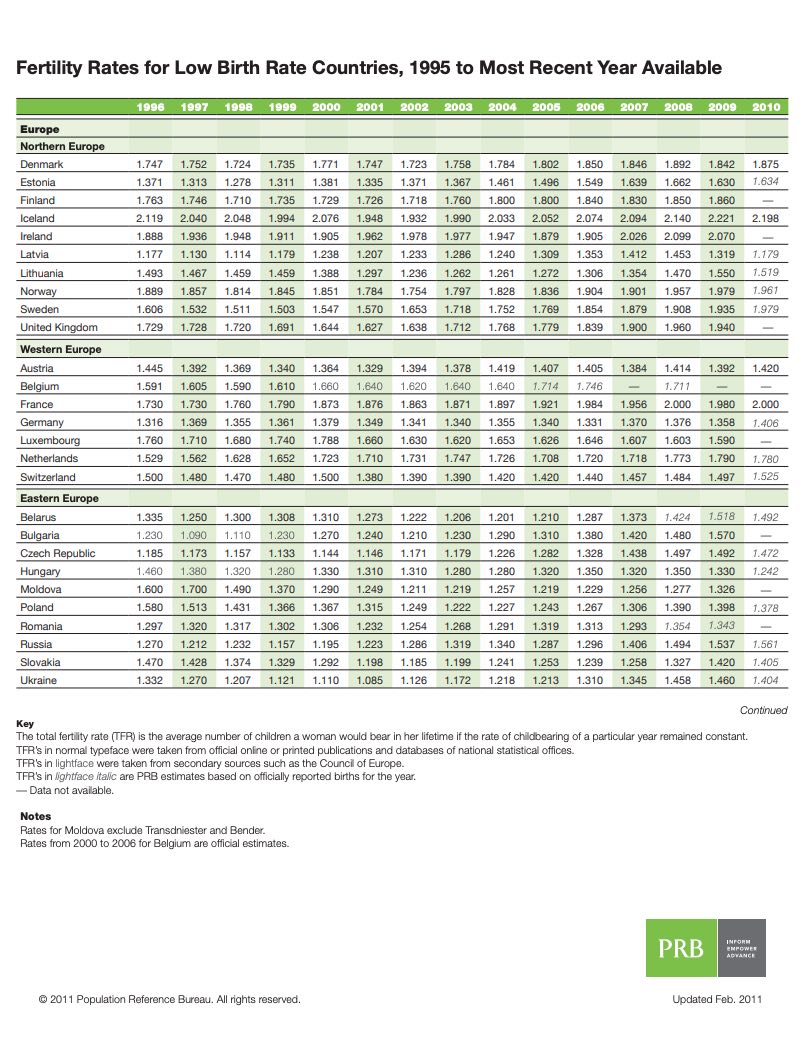

(March 2011) PRB has updated “Fertility Rates in Low Birth-Rate Countries, 1995 to Most Recent Year,” showing birth rate trends in low-fertility countries. More rates are available for recent years and other recent rates obtained from national statistical websites are now final. Interest in birth rate trends in low-fertility developed countries has grown as many of those countries seek to raise birth rates in order to avoid unprecedented aging. Attempts to raise fertility have had modest success at best and, with each passing year, the number of potential future parents dwindles.

“Fertility Rates in Low Birth-Rate Countries, 1995 to Most Recent Year” shows 2010 total fertility rates (TFRs) projected by PRB based on birth data for less than a full year when such data are available. Three countries—France, Italy, and Singapore—have already reported TFRs for 2010. Since the last few months of births in 2010 have not been reported for most countries, final TFRs will naturally be somewhat different.

In order to clarify such a large amount of data, the table below groups countries into fertility change categories. “Very low” fertility countries are defined as having a TFR of 1.6 or lower at some point from 1996 onward. Countries whose low point since 1996 was a TFR of 1.7 or higher are not considered very low fertility countries and, in fact, some of those countries in northern and western Europe have already seen their TFR rise to 1.9 or 2.0.

Fertility Trends in Very Low-Fertility Countries Since 1995

| Riser | Modest Riser | No Signifant Rise and/or Consistent Pattern | Still Declining |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria | Belarus | Austria | Hungary |

| Czech Republic | Cuba | Belgium | Luxembourg |

| Estonia | Greece | Bosnia-Herzegovina | Portugal |

| Russia | Italy | Canada | Singapore |

| Slovenia | Lithuania | China, Hong Kong SAR | Taiwan |

| Sweden | Netherlands | Croatia | |

| Ukraine | Slovakia | Germany | |

| Spain | Japan | ||

| Latvia | |||

| Macedonia | |||

| Malta | |||

| Moldova | |||

| Montenegro | |||

| Poland | |||

| Romania | |||

| Serbia | |||

| South Korea | |||

| Switzerland |

Source: National statistical offices and PRB estimates.

“Riser” countries in the table above have had TFRs of 1.6 or lower at some point since 1995 and are now 0.3 or more above that level. Countries with less than a 0.3 increase but more than 0.2 are “Modest Risers.” All other countries are labeled “No Significant Rise and/or Consistent Pattern.” It is not possible to catch every nuance of TFR fluctuations since countries have shown differing patterns.

For low-fertility countries who wish to raise their birth rate, 2010 looks to be a disappointing year. Many countries that had experienced some TFR rise may have a reversal or a slowdown, patterns often attributed to the current recession. One of the notable successes has been in Russia, where a government program that began Jan. 1, 2007, gives parents who are both Russian citizens the equivalent of $10,000 for a second and subsequent births. The sudden and continuing TFR increase starting in 2007 implies the policy has achieved part of its goal, but a TFR of 1.5 or 1.6 (based on births reported up to November 2010) is still rather low.

At the other end of the spectrum is Taiwan, whose troubles were compounded in 2010 since it was the Year of the Tiger, an inauspicious year for births. Couples who avoided having a child in 2010 have dropped the TFR to 0.9—a world historic low. The Year of the Rabbit, which began Feb. 3, 2010, is much less likely to produce more births than it might otherwise had since it also a Tai Sui year, not auspicious for Rabbits. President Ma Ying-jeou has recently said that increasing the birth rate is one of the country’s highest priorities. As of this writing, there is a proposal to provide monthly family support payments ranging from the equivalent of $100 to $170, depending on a family’s income. The lowest income category, those earning less than $21,000 per year would receive $170 for each child, while higher income groups would receive the lower amount. The estimated cost of the subsidies is $290 million, if approved.

Spain ended a similar program due to budgetary constraints. In 2007, Spain began issuing one-time $3,300 “baby checks” for each birth. The TFR trend from 2007 to 2009 suggests that the program made little difference. Nonetheless, there was an increased number of women seeking to give birth before the end of the program at midnight on Jan. 1, 2011. But only those who had a genuine medical reason for early childbirth, including those requesting Caesarian section, were accepted by maternity hospitals.

Virtually all very low birth-rate countries have begun, or plan to expand, programs to ease the burden of raising children with measures such as cash payments, extended parental leave, and greater access to less expensive day care. When TFRs rise a little, it is often foreign-born women or women of foreign origin who account for much of the increase. In Ireland, for example, more than one-fourth of births are now to foreign-born mothers. Although aging will be the more serious consequence of low fertility than population size, a recent development in Hungary illustrates the psychological impact of population decrease. Hungary’s population fell below 10 million in late 2010. With births down 7.3 percent in the first 10 months of 2010 compared with 2009, the reversal of long-term natural decrease (births minus deaths) seems highly unlikely.

“Fertility Rates in Low Birth-Rate Countries, 1995 to Most Recent Year” will be updated later this year as complete results for 2010 become available.

Carl Haub is a senior visiting scholar at the Population Reference Bureau.

">

">