Elderly Immigrants in the United States

Focus Area

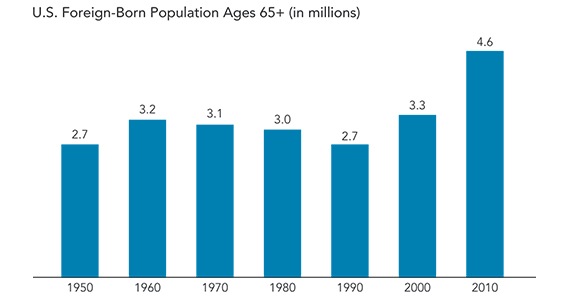

In 2010, more than one in eight U.S. adults ages 65 and older were foreign-born, a share that is expected to continue to grow. The U.S. elderly immigrant population rose from 2.7 million in 1990 to 4.6 million in 2010, a 70 percent increase in 20 years (see figure). This issue of Today’s Research on Aging reviews recent research examining older immigrants in the United States, conducted by National Institute on Aging (NIA)-supported researchers and others. Understanding both the unique characteristics of elderly foreign-born adults and the challenges some of them face is important as policymakers and planners address the well-being and health of the United States’ aging population.

The U.S. Foreign-Born Population Ages 65+ Increased Substantially Between 1990 and 2010.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, historical census data 1950-2000; and Current Population Survey, 2010.

Demographic Trends

Fueling the growth of the U.S. immigrant population ages 65 and older are two trends—the aging of the long-term foreign-born population and the recent migration of older adults as part of family reunification and refugee admissions. Analysis of American Community Survey data suggests that 10 percent of immigrants ages 65 and older had been in the country fewer than 10 years in 2010. Most U.S. immigrants who settle in this country after age 60 are sponsored by their adult children who had immigrated to the United States as young adults.

Long-term immigrants who arrived in the United States as children or young adults tend to face challenges similar to their U.S.-born peers. By contrast, immigrants who migrate after age 60 are often a “potentially vulnerable population” due to limited English language proficiency, little or no U.S. work experience, and weak ties to social institutions, reports Judith Wilmoth of Syracuse University. They face rules barring them from participating in most entitlement and welfare programs unless they become naturalized citizens, but their language skills and age are often barriers to naturalization. Compared to immigrants who arrive earlier in life, late-life immigrants are more likely to be female, to have low education levels, to have limitations in physical functioning, and to be widowed.

Economic Circumstances

Foreign-born elderly tend to have less personal income than U.S.-born elderly, on average. Reliance on a different mix of economic resources in old age accounts for some of the income differences between immigrant and U.S.-born elderly, according to George Borjas of Harvard University. In 2007, U.S.-born elderly ages 65 and older were considerably more likely than immigrant elderly to receive Social Security benefits, investment income, and retirement benefits such as pensions. Immigrant elderly were more likely to be employed than U.S.-born elderly, driven in part by incentives related to Social Security program eligibility.

Immigrant elderly are more likely to have incomes below the poverty line than U.S.-born elderly. In 2010, 8 percent of U.S.-born elderly lived below the poverty threshold, compared to 16 percent of foreign-born elderly. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that within the foreign-born population ages 65 and older, 15 percent of Asian immigrants, 21 percent of all Hispanic immigrants, and 23 percent of Mexican immigrants lived below the poverty line in 2010.

The publication also explores recent research on the living arrangements, life expectancy, health, and disability levels of older immigrants in the United States.

">

">