Improve Antenatal Care in Ghana's Lower-Level Health Facilities

Date

August 27, 2015

Author

Patience Afulani received a Ph.D. at the University of California, Los Angeles and is now a postdoctoral scholar at University of California, San Francisco. She was a participant in PRB’s 2014-2015 Policy Communication Fellows Program, funded by USAID through the IDEA Project. This working paper, written as part of the program, is based on the author’s research and does not necessarily reflect the views of PRB.

(August 2015) Summary: Low-quality antenatal care may be contributing to Ghana’s high maternal mortality rates, according to a recent study. Ninety-six percent of Ghanaian women had at least one antenatal care visit while pregnant and 80 percent of those women had at least four visits, the level recommended by the World Health Organization. However only six in ten (61 percent) women who had one or more antenatal care visit received at least eight of the nine medical tests and services essential to quality care, such as blood pressure testing and information on recognizing pregnancy complications. High-quality antenatal care can save lives by providing simple interventions (such as screening for hypertensive disorders) and by helping women plan ways to access skilled delivery care.

The study found that women who were poor or uneducated were more likely to receive low-quality care than wealthy or more-educated women. Women who received care in lower-level facilities (such as health centers and community clinics) were more likely to receive low-quality care than women visiting higher-level facilities (such as government hospitals or polyclinics). Improving the quality of care in lower-level facilities could reduce maternal mortality and socioeconomic disparities.

The quality of antenatal care (ANC) in Ghana is below recommended levels, especially for poor and uneducated women and in lower-level health facilities—such as health centers, health posts, community clinics, and outreach points—where most poor and uneducated women seek care.1 To reduce socioeconomic disparities and increase the overall quality of Ghana’s antenatal care, the Ghana Health Service needs to improve the quality of care in these lower-level health facilities. Two areas that require urgent attention are:

- Providing essential equipment and supplies for delivering antenatal services.

- Training health workers to educate pregnant women on danger signs during pregnancy and on what to do if they develop a pregnancy complication.

Antenatal visits are an opportunity to reach women with simple interventions that can save the lives of both mothers and babies (such as education on pregnancy complications and screening and treatment of anemia, infections, and hypertensive disorder); and to identify women with complications and start the appropriate management. Furthermore, during antenatal visits, women can be educated and assisted in planning ways to access skilled delivery care, which research shows is critical to reducing maternal mortality.2 This implies that high-quality ANC can help improve the health and survival of mothers and infants—directly through preventative measures and early management of complications, and indirectly through increased use of skilled birth attendants.

Maternal Mortality High, Despite Widespread Use of Antenatal Care

Even though more than 90 percent of pregnant women in Ghana have at least one ANC visit, Ghana is still grappling with high maternal mortality—380 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.3 A recent analysis based on data from the 2007 Ghana Maternal Health survey (a nationally representative population-based survey on maternal death, disability, and illness) suggests that poor quality ANC may be a major contributing factor to this high rate.4

This study defined good quality ANC as receiving at least eight of nine essential antenatal services at any point during pregnancy. Poor quality care is receiving seven or fewer of these services. The nine antenatal services examined included measuring weight and blood pressure, conducting urine and blood tests, prescribing iron supplements and an anthelminthic, vaccinating against tetanus, and instructing women on the signs of pregnancy complications as well as where to seek help in case of a complication.

Most Ghanaian women are not receiving the full benefits of antenatal care. Of the 96 percent of women who attended ANC at least once during pregnancy, 80 percent attended four or more times, the number of visits recommended by the World Health Organization.5 But only 25 percent of women who had at least one visit received all nine essential ANC services across all their visits, and only 61 percent received eight or nine services—the level considered good quality ANC.

Poor or uneducated women tend to receive low-quality antenatal care. Specifically, only 45 percent of the poorest women received good quality ANC compared to 76 percent of the wealthiest women; 48 percent of women with no education received good quality ANC compared to 70 percent of those with a secondary school education or higher. Poor women with no education receive the lowest quality of care: Only 40 percent of them received good quality ANC compared to 65 percent of the wealthiest women with no education.

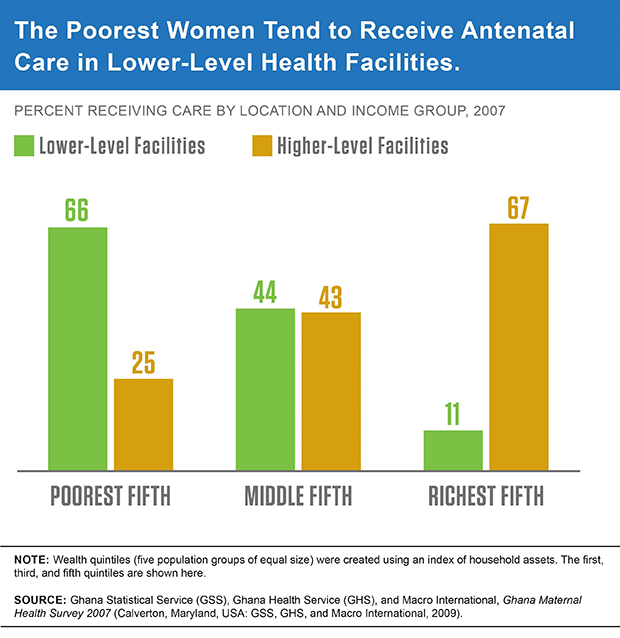

Lower-level health facilities are less likely to provide high-quality care. There are a number of reasons for the differences in quality of care based on socioeconomic background.6 Different groups tend to use different types of health facilities that may provide care of different levels of quality care. The study found that poor women and women with limited education are more likely to use the lower-level health facilities than richer and more-educated women: 66 percent of the poorest women used the lower-level health facilities compared to only 11 percent of the richest women (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Additionally, 55 percent of women with no education used the lower-level facilities compared to 15 percent of those with a secondary education or higher.

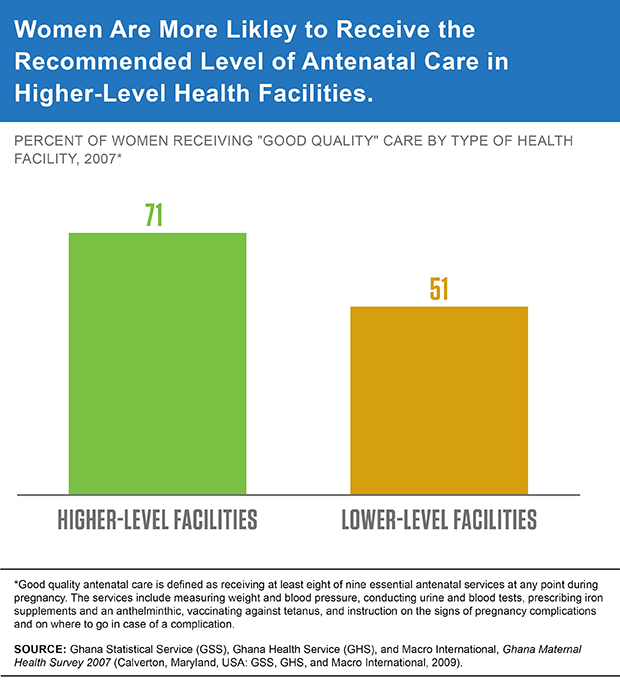

When the analysis separated women by the type of health facilities, it showed that women who receive ANC in lower-level health facilities are more likely to receive poor quality care: 51 percent of all women who received ANC in lower-level health facilities received good quality care compared to 71 percent of women who received ANC in a higher-level facility, such as a government hospital or polyclinic (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

To Reduce Disparities, Improve Care in Lower-Level Health Facilities

These findings suggest that improving the quality of antenatal care in the lower-level health facilities could reduce socioeconomic disparities and increase the overall quality of antenatal care in the country. The Ministry of Health (the policymaking agency) and the Ghana Health Service (the implementing agency) need to take action by providing funding, logistics, and other programmatic support to ensure that all women in Ghana receive good quality ANC. These actions are most urgently needed in the lower-level health facilities.

Donor agencies can support the Ministry of Health with funding and technical support to improve quality by:

- Providing essential equipment and supplies for delivering antenatal services, such as sphygmomanometers, glucometers, urine dipsticks, weighing scales, and rapid diagnostic kits for anemia, malaria, and HIV;

- Providing refresher training for health workers, especially in counseling and educating women on recognizing and responding to pregnancy complications;

- Ensuring effective monitoring and supervision; and

- Providing incentives to attract and retain qualified personnel for the lower-level health facilities.

References

- Patience Afulani, “Determinants of Maternal Health and Health-Seeking Behavior in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Role of Quality of Care,” dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 2015; and Patience Afulani, “Rural/Urban and Socioeconomic Differentials in Quality of Antenatal Care in Ghana,” PloS One 10, no. 2 (2015): e0117996.

- World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF, Antenatal Care in Developing Countries: Promises, Achievements and Missed Opportunities: An Analysis of Trends, Levels and Differentials, 1990-2001 (Geneva: WHO, 2003); and O. Campbell and W. Graham, “Strategies for Reducing Maternal Mortality: Getting on With What Works,” Lancet 368, no. 9543 (2006): 1284-99.

- WHO et al., Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2013 (Geneva: WHO, 2014); and Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Service (GHS), and Macro International, Ghana Maternal Health Survey 2007 (Calverton, Maryland, USA: GSS, GHS, and Macro International, 2009).

- Afulani, “Determinants of Maternal Health and Health-Seeking Behavior in Sub-Saharan Africa”; Afulani, “Rural/Urban and Socioeconomic Differentials in Quality of Antenatal Care in Ghana;” and GSS, GHS, and Macro International, Ghana Maternal Health Survey 2007.

- WHO and UNICEF, Antenatal Care in Developing Countries; and J. Villar et al., “WHO Antenatal Care Randomised Trial for the Evaluation of a New Model of Routine Antenatal Care,” Lancet 357, no. 9268 (2001): 1551-64.

- C. Boller et al., “Quality and Comparison of Antenatal Care in Public and Private Providers in the United Republic of Tanzania,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 81, no. 2 (2003):116-22; P. Hutchinson, M. Do, and S. Agha, “Measuring Client Satisfaction and the Quality of Family Planning Services: A Comparative Analysis of Public and Private Health Facilities in Tanzania, Kenya, and Ghana,” BMC Health Services Research 11, no. 1 (2011): 203; and S. Gabrysch and O. Campbell, “Still Too Far to Walk: Literature Review of the Determinants of Delivery Service Use,” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 9, no. 1 (2009): 34.