New Measure Could Track Progress in Eliminating U.S. Health Insurance Disparities

(November 2013) Extensive U.S. research has documented troubling racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care, but a new analysis suggests that U.S. blacks and Hispanics face more severe disparities than previously thought.

Not only were U.S. blacks and Hispanics more likely to lack health insurance than non-Hispanic whites in 2008, but they also tended to spend much more of their lives simultaneously uninsured and at high risk of needing medical care, reported James Kirby, senior social scientist at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and Toshiko Kaneda, senior research associate at the Population Reference Bureau (PRB) in an article in the October 2013 issue of Health Affairs.

Their findings are based on a measure they created that quantifies racial and ethnic disadvantages over a typical lifespan rather than at just one point in time. As key insurance coverage provisions of the Affordable Care Act begin to take effect, this new measure can serve as a benchmark to help policymakers monitor progress toward eliminating racial and ethnic differences.

“Research consistently shows that having insurance is linked to better health,” said Kaneda. “Our measure reframes the discussion by focusing on how long people spend uninsured while in potentially poor health, a state we call ‘health insurance double jeopardy.’ ” The combination of poor health and no health insurance increases the likelihood that an illness or accident will lead to serious financial problems, further exacerbating socioeconomic disadvantages, she noted.

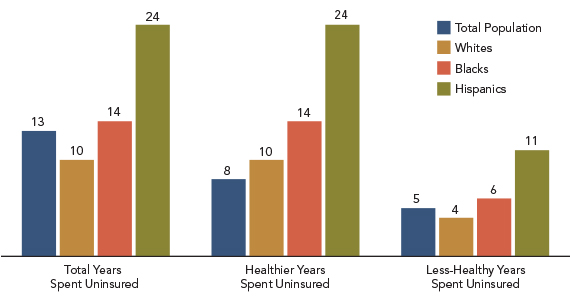

Employing statistical techniques used to calculate life expectancy, they estimated how long whites, blacks, and Hispanics could expect to spend both uninsured and at high risk of needing medical care if insurance coverage and self-reported health levels remained unchanged. On average, Americans could expect to spend 13 years of life without health insurance given age-specific health insurance coverage and death rates in 2008 (see figure), they found. But this national total masks wide racial and ethnic disparities, Kirby pointed out.

Expected Years Spent Uninsured, by Anticipated Health Level and Race/Ethnicity, 2008

Note: Blacks and whites include non-Hispanics only.

Source: James Kirby and Toshiko Kaneda, ” ‘Double Jeopardy’ Measure Suggests Blacks and Hispanics Face More Severe Disparities Than Previously Indicated,” Health Affairs 32, no. 10 (2013): 1766-72.

“Hispanics are by far the most disadvantaged, with an uninsured life expectancy of 24 years—nearly 30 percent of their total life expectancy—and with 11 of those years spent in double jeopardy, with no insurance but high medical need,” he said. “In comparison, uninsured life expectancy is 14 years for blacks and 10 years for whites, with 6 and 4 years, respectively, spent in health insurance double jeopardy.”

Identifying the Most Vulnerable

For their analysis they used data from the nationally representative 2008 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Insurance coverage was based on rates for June 2008. They identified individuals at risk of needing health care in the near future based on the answer to the question, “In general, compared to other people your age, would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” Earlier research indicated that answering poor, fair, or good strongly predicts disease and death, even after clinically diagnosed conditions are taken into account. (For example, Kirby and Kaneda found that compared to those who reported being in excellent or very good health in 2007, those who reported being in poor, fair, or good health were twice as likely to have an emergency department visit; were three times more likely to be hospitalized; and spent, on average, $3,600 more on health care in 2008.)

The Affordable Care Act is expected to reduce racial and ethnic health insurance disparities. By taking age structure and future health care need into account, Kirby and Kaneda’s new measure can show how those reductions are achieved. If the act mainly increases insurance coverage among young, relatively healthy people, it might not decrease the time minorities spend with high medical need but no insurance, according to Kaneda.

“Increasing the proportion of older working-age adults who have health insurance would likely be a more effective way of limiting the highly vulnerable period of health insurance double jeopardy,” she said.

Unlike other measures currently in use (such as percentage with no insurance), Kirby and Kaneda’s approach combines insurance coverage and future medical need to create a simple-to-interpret measure to track progress toward eliminating racial and ethnic disparities.

For more information: James Kirby and Toshiko Kaneda, ” ‘Double Jeopardy’ Measure Suggests Blacks and Hispanics Face More Severe Disparities Than Previously Indicated,” Health Affairs 32, no. 10 (2013): 1766-72.