Paola Scommegna

Contributing Senior Writer

U.S. children of incarcerated parents are an extremely vulnerable group, and much more likely to have behavioral problems and physical and mental health conditions than their peers, reports Kristin Turney, a University of California-Irvine sociologist.

“We know that poor people and racial minorities are incarcerated at higher rates than the rest of the population,” she says. “Incarceration is likely compounding the disadvantages their children face, setting them further behind, and contributing to racial and social class inequalities in children’s health.”

Turney compared children under age 18 with similar socioeconomic characteristics and family backgrounds and found that having a parent in prison or jail was linked to a greater incidence of a variety of conditions, including poor health; attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADD/ADHD); behavioral or conduct problems; learning disabilities; anxiety; and developmental delays.1 In particular, children with an incarcerated parent were more than three times more likely to have behavioral problems or depression than similar children without an imprisoned parent, and at least twice as likely to suffer from learning disabilities, ADD/ADHD, and anxiety.

This study is the first to use a nationally representative sample to examine the health of children whose parents have spent time behind bars (the 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health), and serves to underscore “how widespread and detrimental this stressor is in children’s lives,” according to Turney.

She is also among a group of researchers using the Fragile Families and Children Wellbeing Study to understand the effects of incarceration on crucial aspects of child development, including parent-child relationships, school difficulties, and homelessness.

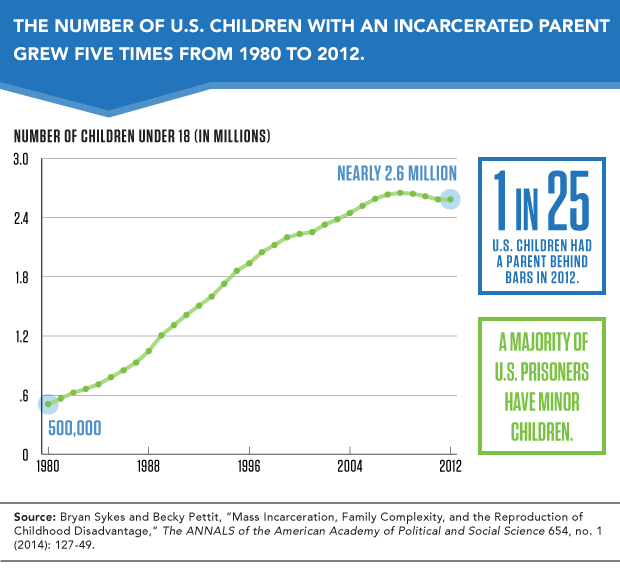

The United States has more than 2 million people behind bars, giving it the world’s highest incarceration rate of roughly 700 per 100,000 residents.2 This high rate is largely attributed to recent “get tough on crime” policies and the war on drugs that jailed more people for longer periods. A majority of U.S. inmates have minor children and 45 percent were living with their children before they were imprisoned, reports the Bureau of Justice Statistics.3

The high incarceration rate in the United States means that a large share of children, especially poor and minority children, experience the incarceration of a parent,” comments Turney.

The number of children with a parent in prison or jail grew five times between 1980 and 2012, growing from about 500,000 to 2.6 million, according to recent estimates by sociologists Bryan Sykes of University of California-Irvine and Becky Pettit of University of Texas-Austin (see figure).4 At any given time, nearly 4 percent of U.S. children younger than age 18 are separated from a parent because of incarceration. Imagine one child in every classroom of 25 students.

But rather than being distributed evenly throughout the nation’s population, Turney is quick to point out that incarceration is starkly concentrated, leaving some children more likely to have an incarcerated parent than others. Among black children whose fathers lacked a high school diploma in 2009, about 64 percent will experience parental incarceration by age 17, compared with about 15 percent of white children with similarly educated fathers, Sykes and Pettit report.5 On any given day in 2012, one in nine black children had a parent in custody, they find.

In Turney’s view, the impact on children is “an overlooked and unintended consequence of mass incarceration.” She suggests that health professionals and social workers in communities where incarceration is common should consider screening children for parental incarceration because of the dramatically elevated risk of health and behavioral problems—risks that she found were higher than for children who experienced other sorts of childhood stress such as divorce or living with a mentally ill parent.

For example, children with an incarcerated parent face a greater risk of ADD/ADHD than children who experienced either parental divorce or death, she found. Did the stress of a parent going to prison causes attention problems? The study was not designed to answer this question because it examined children at only one point in time. “It is not possible to determine if the attention problems existed before the parent was imprisoned, to know if it is the environment or genetics,” Turney explains.

But by tracking 5,000 urban children and their predominantly unmarried parents over nine years, the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study offers researchers a chance to isolate the role of incarceration on children and families. Nearly half the fathers surveyed in the study have been imprisoned at some point in their lives, and one in three have been incarcerated since their child was born. Researchers are able to “tease out the nuances and understand which children are most at-risk,” says Turney.

For example, children who are living with their fathers before they are incarcerated are much more likely to develop behavioral problems (acting out or breaking rules, or attention difficulties such as impulsivity or daydreaming) than children who live elsewhere.6 But when an abusive father is imprisoned, researchers find no measurable effects on the development and behavior of their children. Jailing an abusive father may protect the children, the researchers suggest.

The Fragile Families data also show that having a recently incarcerated father dramatically increases a child’s risk of being homeless, even after socioeconomic characteristics and previous housing problems are taken into account.7 The researchers suggest that fathers’ imprisonment contributes to homelessness indirectly by limiting resources available to mothers and children. They document not only the father’s lost income but also a drop in social support, various forms of public assistance, and the mother’s capacity to cope (measured by increases in depression and stress).

Using the Fragile Family data, Turney found that increases in mothers’ neglectful and physically aggressive behaviors toward their children after fathers left for prison were related to depression, economic insecurity, and changes in the parents’ relationship.8

In another study, she examined why children whose fathers are incarcerated are more likely to be held back a grade in early elementary school than their peers.9 Results show that teachers’ assessments of the child’s abilities—

rather than test scores or behavioral problems—play the major role in the decision to require a child to repeat a grade. Teachers may be able to identify weakness in these children that test scores cannot measure or they may be biased in some way, according to Turney.

These findings suggest that teachers, school administrators, and school social workers may benefit from training that increases their awareness, support, and sensitivity toward the challenges faced by children of incarcerated fathers, she says.

The strong links between parental incarceration and child health and behavioral problems, should lead to a rethinking of sentencing policies, particularly for nonviolent offenders, she suggests.

“A large number of parents, especially fathers, are incarcerated for nonviolent offenses affecting not only their life chances but the life chances of their children,” she says. “This is certainly an unintended consequence of the prison boom.”