Reducing Maternal Deaths in West and Central Africa

Date

August 27, 2015

Author

Comfort Olorunsaiye recently earned a Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina-Charlotte. She was a participant in PRB’s 2014-2015 Policy Communication Fellows Program, funded by USAID through the IDEA Project. This article, written as part of the program, is based on the author’s research and does not necessarily reflect the views of PRB.

(August 2015) Summary: Maternal deaths can be prevented when women give birth in health facilities attended by skilled personnel. A study in seven West and Central African countries shows that poor women and women who live in impoverished rural or urban communities are less likely to deliver in a health facility than wealthy women and those who live in wealthy communities. Providing vouchers to cover health care costs for low-income pregnant women and expanding the number of trained midwives in poor communities could remove the obstacles to delivery with a skilled birth attendant and help to prevent maternal deaths.

Each year, more than 100,000 women in West and Central Africa die from pregnancy-related causes—mostly during labor and delivery, or soon after—more than in any other region of the world.1 Maternal deaths are tragedies; these deaths also put the health and survival of children at risk and threaten economic development, yet the vast majority of maternal deaths are preventable.

A large body of research finds that one of the best ways to prevent maternal deaths is to ensure that women give birth under the supervision of skilled personnel.2 When women give birth in a health facility, they are likely to have trained personnel in attendance. But many women who stand to benefit from this critical intervention still give birth at home without the skilled care needed to avert or address unexpected complications and assure safe delivery.

Household Income and Community Wealth Make a Difference

One well known reason women often do not deliver in a health facility is lack of money, either for transport, health services, or other related costs.3 A recent study in seven West and Central African countries—Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Togo—took a deeper look at this issue.4

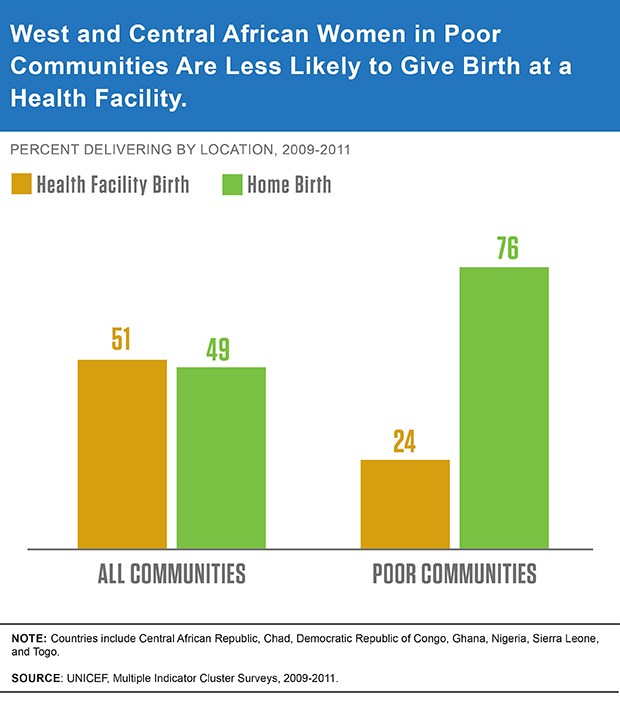

The researchers found that along with individual wealth, location makes a difference. In the seven countries, only about one-half of all births are in a health facility. For women who live in poor communities, whether urban or rural, this share drops to slightly fewer than one in four (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

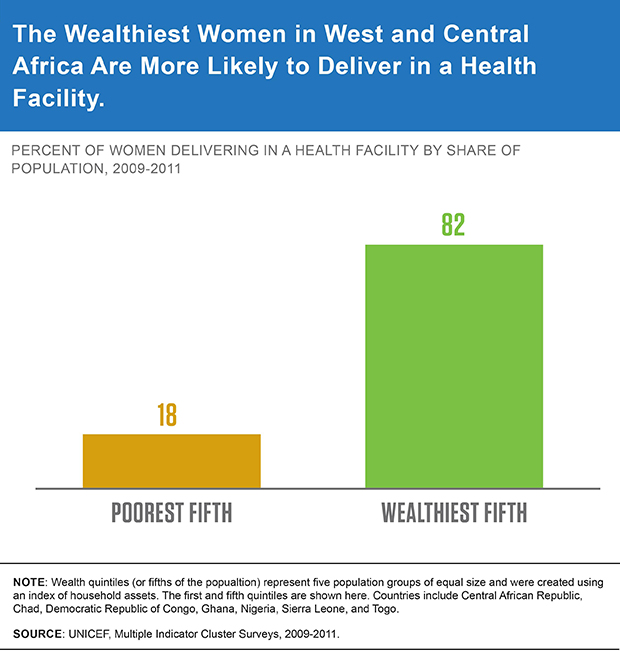

In poor communities, more than 80 percent of the wealthiest women (those whose household income was in the top 20 percent) in those communities deliver at a health facility compared to less than 20 percent of the poorest (see Figure 2). These findings suggest that being very poor in a poor community poses special barriers to facility-based delivery.5

Figure 2

There are several possible explanations for why the poorest women are least likely to deliver in health facilities. Poor communities typically have weak or nonexistent health facilities.6 Very poor women do not have the resources needed for transportation or other costs to seek care at facilities elsewhere. They may be forced to contend with long wait times and other challenges at understaffed and under-resourced facilities in their communities, and these conditions may deter them from seeking care. Even in countries that offer free health care for women and children, out-of-pocket costs for supplies such as disinfectants and other cleaning agents can still keep facility-based delivery out of reach.7

Ways to Reduce Maternal Deaths in West and Central Africa

To reduce the exceptionally high rate of pregnancy-related deaths in West and Central Africa, policymakers need to address potentially hidden inequities by improving physical access to maternal health care on the one hand, and removing financial barriers to skilled delivery care on the other.

Governments can start by adopting strategies that have shown considerable promise in similar settings, such as cash transfers (payments directly to mothers). In Kenya, facility-based delivery and the use of postnatal care among the poorest women doubled following the introduction of a reproductive health voucher program in three districts.8

Training and deploying midwives to provide skilled birth attendance to women in their communities can also reduce maternal deaths. In Nigeria, the Midwives Service Scheme trained newly graduated, unemployed, or retired midwives, and employed them in underserved areas. In target areas, this initiative resulted in a 60 percent increase in the use of prenatal care, and a nearly 50 percent increase in childbirths attended by a health professional.9

With these few critical steps, the region can take action toward saving the invaluable lives of hundreds of thousands of mothers. By reducing preventable maternal deaths, West and Central Africa can also reduce child deaths and improve overall economic development.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF, Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2013: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank and United Nations Population Division (Geneva: WHO, 2014).

- Kavita Singh et al., “Gender Equality and Childbirth in a Health Facility: Nigeria and MDG5,” African Journal of Reproductive Health 16, no. 3 (2012): 122-28.

- Olatunde Aremu, Stephen Lawoko, and Koustuv Dalal, “Neighborhood Socioeconomic Disadvantage, Individual Wealth Status and Patterns of Delivery Care Utilization in Nigeria: A Multilevel Discrete Choice Analysis,” International Journal of Women’s Health 3 (2011): 167-74.

- Comfort Olorunsaiye, “Multilevel Determinants of Facility-Based Delivery in West and Central Africa,” unpublished manuscript, May 2015.

- Olorunsaiye, “Multilevel Determinants of Facility-Based Delivery in West and Central Africa.”

- M. Mahmud Khan et al., Geographic Aspects of Poverty and Health in Tanzania: Does Living in a Poor Area Matter? Health Policy and Planning 21, no. 2 (2006): 110-22.

- Chitalu M. Chama-Chiliba and Steven F. Koch, “Assessing Regional Variations in the Effect of the Removal of User Fees on Institutional Deliveries in Rural Zambia,” ERISA Economic Research Southern Africa Working Paper 427(April 2014); Adam Wagstaff, “Poverty and Health Sector Inequalities,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 80, no. 2 (2002): 97-105; and P. N. Ebeigbe, “Reducing Maternal Mortality in Nigeria: The Need for Urgent Changes in Financing for Maternal Health in the Nigerian Health System,” The Nigerian Postgraduate Medical Journal 20, no. 2 (2013): 148-53.

- Francis Obare et al., “Community-Level Impact of the Reproductive Health Vouchers Programme on Service Utilization in Kenya,” Health Policy and Planning 28, no. 2 (2013): 165-75.

- Seye Abimbola et al., “The Midwives Service Scheme in Nigeria,” PLoS Medicine 9, no. 5 (2012): e1001211.