Time With Parents Key for Adolescents

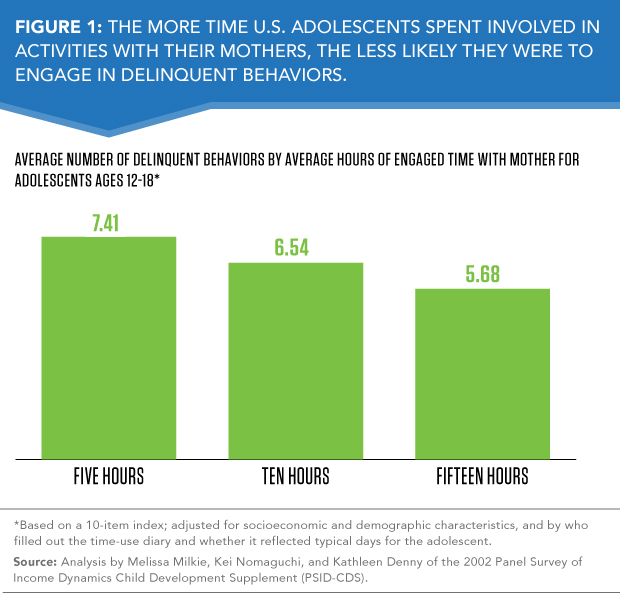

(April 2015) The more time mothers spent engaged in activities with their adolescent children (ages 12 to 18), the less teens were involved in delinquent behavior, such as skipping school, shoplifting, staying out at night without permission, and getting in trouble at school or with the law, according to a study in the most recent issue of the Journal of Marriage and Family (see Figure 1).1

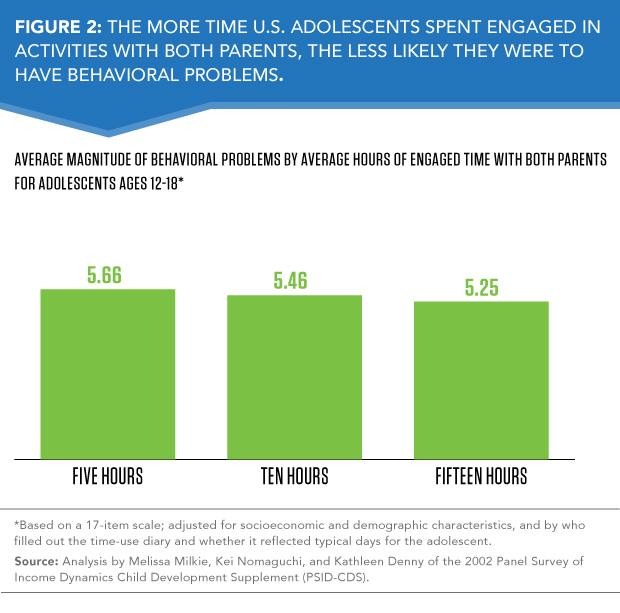

The findings also show that the amount of “parent time”—the time mothers and fathers spent together engaged in activities with their teens—was linked to fewer behavioral problems, higher math scores, less substance abuse, and less delinquent behavior among adolescents (see Figure 2).

In contrast, the research team found no strong relationship between the amount of time mothers spent with younger children (ages 3 to 11) and children’s behavioral or emotional problems, or their math or reading scores. This held true whether the time mothers spent was engaged time—time spent directly engaged in activities with their children, or accessible time—time in which they were accessible to their children but not engaged in joint activities with them.

“It is ironic that most of the cultural pressures on mothers center on mothers’ presence and interactions with younger children, with less attention to adolescents, when adolescence may be a key stage in terms of the influence of time with parents,” wrote Melissa Milkie, University of Toronto, Kei Nomaguchi, Bowling Green State University, and Kathleen Denny, University of Maryland.

The researchers point out that mothers who had young children with emotional, behavioral, or academic difficulties may have chosen to spend more time with them than mothers of children not experiencing such difficulties. This may partially account for the weak relationship between the amount of maternal time and child well-being. The study also found no strong relationship between either the amount of father’s time or parent time and younger children’s behavioral, emotional, or academic outcomes.

Quantity Versus Quality Time

The researchers measured the amount of time mothers spent with children and the type of time (either engaged time or accessible time), but not the quality of the time. For example, they did not distinguish between mother-child interaction time spent eating meals (an activity considered high-quality because of direct interaction and conversation) versus time together watching television. “Given that the amount of maternal time in childhood was unrelated to well-being, it is important to know the kinds of time or ‘quality’ of activities the children are doing with mothers,” the authors said.

The finding that the overall quantity of time mothers spent with young children is largely unrelated to child development and child well-being is underscored by another recent study published in Demography. Using the PSID-CDS data but a somewhat different study design, researchers Amy Hsin and Christina Felfe found that the quantity of time mothers spent with their young children was related to slightly worse cognitive and behavioral outcomes for children under age 6 and slightly better behavioral outcomes for children ages 6 and older.2 The quality of the activities children are engaged in when they are with their mothers may explain these differences: The researchers found that spending large amounts of unstructured time with their mothers (for example, watching television) was linked to poorer outcomes, especially among younger children.

Yet, the study also showed that more maternal time in educational activities (such as reading) was associated with positive cognitive and behavioral outcomes for young children, as well as positive cognitive outcomes for children ages 6 and older. In addition, more maternal time in structured activities (like eating meals or attending events) was also linked with positive behavioral outcomes for older children. These findings indicate that for young children, the benefits of “quality” time with mothers in educational activities may be offset by large amounts of “non-quality” time in unstructured activities (such as watching television), resulting in a negative overall association between the amount of maternal time and children’s cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Both studies show that the relationship between maternal time and child well-being depends on the age of the child and the type of time that is spent.

Parent-Child Time Tracked Via Diaries

For both of these studies, the researchers used time-diary data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, Child Development Supplement (PSID-CDS), a nationally representative sample of U.S. families with children. In the time diaries, children’s activities were recorded in sequence for a 24-hour period, including a randomly sampled weekend day and weekday. Time diaries provide high-quality data on how people spend their time, what activities they do, with whom they do the activities, where the activities take place, and who else is present. Parents are less likely to inflate time spent with children because respondents record their time in activities done in sequence and the activities must add up to 24 hours. The PSID-CDS collects information on how typical the diary days were for the child, and the researchers took this information into account in their analyses to ensure the reliability of the time measure.

Other Factors Affect Children’s Well-Being

Consistent with prior research, the Journal of Marriage and Family study also found that social and economic resources, such as mothers’ education, as well as family structure (married couple family versus single-parent family or stepfamily) and mothers’ distress (her level of anxiety and depression) were important factors related to children’s and adolescents’ well-being. The researchers suggest that supporting mothers in ways that improve their resources and maintain their health can support the well-being of U.S. children.

References

- Melissa A. Milkie, Kei M. Nomaguchi, and Kathleen E. Denny, “Does the Amount of Time Mothers Spend With Children or Adolescents Matter?” Journal of Marriage and Family 77 (2015): 355-72.

- Amy Hsin and Christina Felfe, “When Does Time Matter? Maternal Employment, Children’s Time with Parents, and Child Development,” Demography 51 (2014): 1867-94.