Immigration: Shaping and Reshaping America

Product: Population Bulletin

Authors: PRB

Date: December 11, 2006

The Population Bulletin Update, “Immigration in America 2010,” released in June 2010 is a follow-up to 2006’s Population Bulletin, “Immigration: Shaping and Reshaping America” by Philip Martin and Elizabeth Midgley, and provides new data and analysis on the economic impacts and policy debates around immigration.

(December 2006) Recent waves of immigrants have brought greater diversity to the population in the United States. Between 1990 and 2005, 14.5 million immigrants—an average of almost 1 million a year—became permanent legal U.S. residents. Another 500,000 or more settled here illegally each year.

While the United States has always celebrated its immigrant heritage, Americans continue to worry about the economic, political, and cultural implications of immigration. Some groups say that immigration should be limited. They contend that immigrants contribute to excessive population growth and environmental degradation, take jobs away from low-skilled American workers, depress wages, and impose a heavy burden on educational, medical, and other state and local services. Other groups propose removing limits on immigrants because the influx of new consumers and workers helps expand the economy and enrich society.

A new and updated edition of the Population Bulletin, “Immigration: Shaping and Reshaping America,” offers an overview of immigration to America. The report covers immigration patterns and policies in the United States, reviews the peaks and valleys of immigration flows, and offers a historical perspective on contemporary migration that includes a focus on immigration’s economic impact.

The Bulletin was written by Philip Martin, professor of agricultural economics at the University of California-Davis, chair of the University of California’s Comparative Immigration and Integration Program; and Elizabeth Midgley, a long-time observer and analyst of U.S. immigration trends and policy formation. U.S. immigration policy will continue to change in response to immigration flows and their impacts on Americans. “To resolve the fundamental economic, social, and political issues raised by immigration,” the authors write, “we must weigh the choices or tradeoffs between widely shared but competing goals in American society.”

Resources

View All

PRB Discuss Online: Who Is Malnourished or Hungry in the World? Why? What Can We Do to Help?

Date

December 6, 2006

Author

PRB

(December 2006) How many malnourished or hungry people are there in the world, and why? Is the situation improving or worsening?

During a PRB Discuss Online, Bill Butz, president and CEO of PRB, answered participants’ questions about malnutrition, hunger, and food security.

Dec. 6, 2006 10 AM EST

Transcript of Questions and Answers

Dr.B.Vijayakumar: The causes for malnourishment is universally same. But it is different from hungry,but can be related. In places like highly vegetative African nations,even though nutrient natural foods are available,the population suffers. How the problem can be solved?

Bill Butz: Indeed, malnutrition and hunger are related, although malnutrition is more straightforward to define and measure. You raise an interesting question about natural or traditional foods. In many parts of the world, these have been a source of good nutrition for centuries, at least. Amaranth (a kind of greens that are boiled) and Bambara Bean are among many such foods in Africa. Environmental degradation has decreased production of natural crops in some areas. And generally, peoples’ food preferences change toward more “modern” grains and toward animal protein as their income rises and as they become exposed to mass media messages. Compared to research on more modern crops, very little agricultural research has been devoted to improving the characteristics and production of native crops, with exceptions like the the substantial research on casava.

Carlos Teller: Why is the main donor response (in dollars) to problems of hunger and malnutrition in the world is food aid? Evaluation research has shown that this has very little effect on the causes and prevention. what can be done to get over the overly “FOOD FIRST” approach?

Bill Butz: Well, it’s natural to think that a good way to help a hungry person or a hungry nation is just to provide food. And that is a correct approach in the case of famine and starvation, where the problem is acute and the need is urgent. For the longer run, though, when there is chronic malnutrition and hunger that continues, providing food has the unfortunate effect of lowering food prices in the receiving country and thereby blunting the incentives for local farmers to produce. This usually worsens the situation in the long run. Keep in mind that one of the main impetuses behind food aid programs is not reducing hunger in the receiving country but propping up product prices in the sending country! When the U.S. government, for example, buys grains and dairy products on the U.S. market, it keeps those prices higher for farmers. If there’s no world market at those prices, the U.S. government and others have frequently given the food away abroad or sold it abroad for local currencies.

Christopher Wamala: One who is Hungry or malnourished is one who is sick or who doesn’t have the tools or the seeds or the knowledge to have to use to fight hunger or malnutrition. One can be affected of war or by disease. Kind people, individuals or organisations, should make grants to the poor direct to them, not through governments. Donors should insist on such projects that encourage giving out tools or seeds to involving the people themselves in food productions. Donors should arrange to help to end wars which have been the major causes od hunger or malnutrition of the whole world.

Bill Butz: In one sentence, Christopher, you hit most of the direct causes of malnutrition and hunger: disease, farmers’ lack of inputs, and lack of knowledge about healthy eating and other behaviors. More broadly, it’s useful to think about three levels of causes: food availability, food access, and food utilization. “Availability” has to do with food production. “Access” has to do with income, education, information, and other cultural and economic factors that affect how consumers obtain food. “Utilization” refers principally to how the body makes use of its nutrient intake and what the results are. You’re right that grants through governments have a spotty history. But the other ways of getting resources to poor people have their problems, too. For instance, most NGO’s (non-governmental organizations) don’t have nearly a universal reach to all the malnourished or hungry in a country; instead they may serve city dwellers, or people who make use of a particular service. As for wars, yes, these along with severe civil disturbances and natural disasters like floods, droughts and earthquakes do still cause famine and starvation. But these are very far from the major causes of malnutrition and hunger, anymore. Chronic malnutrition is a much more important problem in terms of the numbers of people affected and the results for themselves and their countries.

Joanna Vandenberg: Many scientists now say that the green revolution was a bad idea. It created a huge population living under sub-standard conditions. do you agree or disagree with that? and can you explain why?

Bill Butz: The green revolution (improved cereal grain varieties and associated changes in other agricultural inputs and practices, from the late 1960s through the early 1980s) had many effects. Certainly, it substantially raised the production of cereal grains in South and Southeast Asia and Latin America. In those same regions, these increases in food production and availability reduced malnutrition and hunger, and thereby decreased infant mortality and increased life expectancy. So there are indeed many more people living in the world today than would have been without the green revolution. To the extent that this is a bad thing, then the green revolution (along with other important factors) was responsible. The green revolution led also to increased use of chemical fertilizer and pressure on groundwater supplies. The green revolution hardly took effect in Africa, so the effects are missing there. Personally, I think that the green revolution was on net an enormous benefit to humankind, not withstanding it’s flaws, from which I think we’ve learned.

Max: Extreme poverty often occurs in developing countries with high rate of unemployment. So if more people from these countries can migrate to rich,developed countries with underpopulation problems, will it help to relieve poverty?

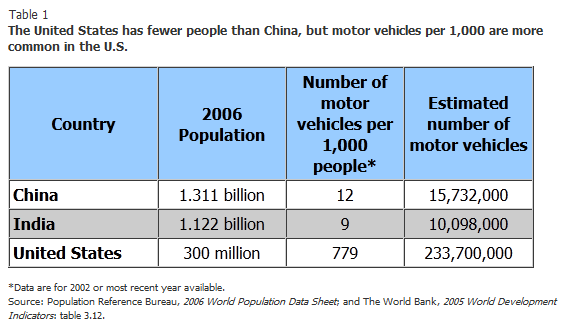

Bill Butz: International migration is, indeed, one of the ways that people improve their economic condition. Migration from developing to developed countries is widespread, but migration between developing countries is on the rise. Guatemalans crossing into Mexico, for example. Such migration does generally improve the standard of living of the migrants (and often also of the family they leave behind but send money to). That fact doesn’t do away, though, with the issues and arguments that attend such migration in both sending and receiving countries!

Soma Dey: Do you think that the hungry nations are a threat to the world security? Hungry people are more dangerous than nuclear weapons?

Bill Butz: Personally, Soma, I think that the fact that about half of all the child deaths in the world this year have a cause in malnutrition is the most important reason to be concerned about the things we’re all talking about this morning. That’s 15,000 deaths a day.Hunger used to be an important cause of conflict, but research indicates that it’s much less so today. Other causes predominate. Some observers think that hunger may again become a major factor in world insecurity if natural resource degradation causes food production declines so severe to cause acute malnutrition and famine in particular areas in the future.

Christine: After working this summer in a nutrition program that was an integrated part of a child survival program in Rwanda, I concluded that unless nutrition programs are implemented alongside microfinance or microenterprise programs, their efficacy may be limited. Could you comment on this?

Bill Butz: Community involvement is a key to solving “access” constraints that produce malnutrition. What direction this involvement best takes depends strongly on local conditions. Much research supports this conclusion. I have not personally seen research that links microfinance or microenterprise programs to child survival. But I certainly expect that where access to credit and to income are constraining food access and other contributors to child survival, such programs can be effective. I am a strong supporter of them for other reasons, as well.

Anonymous: How effective are programs like “Feed the children”, “Save a child” and “wateraid” in helping to combat malnourishment among children, particularly the poor?

Bill Butz: Programs that deliver food to famine areas have become more and more effective in recent decades. The principal constraint is getting the food from the loading dock to needy people’s mouths. Country governments are sometimes unhelpful, and civil disrest and civil war are just as often the problem. To reduce chronic malnutrition, a sustained approach that does not directly supply food from abroad and therefore does not reduce the incentives for local farmers to produce food and and reduce farmers’ income is the right idea. There are many programs that can do this, including ones that raise the income of the poor, that increase the schooling and status of women, and that improve food-related behaviors through information. Fortunately, there are many excellent programs, rich country-based and international, that take one or another of these approaches and contribute importantly.

Robert Prentiss: A nation’s IMR, if less than 50, has been used to determine whether that country has succeeded in ending hunger. If you consider that methodology to be valid, what countries have managed to lower their IMR’s to below 50 in the past 5 years. Have any backslided in that period to above 50?

Bill Butz: Falling infant mortality rates are one of humankinds’ major successes of the 20th century, first in the developed countries, then also in the developing world in the last 40 years. Accompanying these mortality declines, and partly responsible for them, have been substantial reductions in malnutrition. The number of undernourished people in developing countries fell from 920 million in 1980 to 798 million in 2001. The proportion undernourished fell from 28% to 17 percent. These numbers are extraordinary and give us substantial hope that IF WE CONTINUE AND IMPROVE THE INVESTMENTS WE’VE BEEN MAKING OVER THIS PERIOD, malnutrition and infant mortality can continue to fall. Quite a number of countries have moved under the 50 mark in the last decade. Few have backslid; these would include HIV/AIDS ravaged countries like Zimbabwe.

Okpechi Felix-Mary Uzochi: It is inherent in the millennium development goals to eradicate extreme hunger and poverty by the year 2015.Do you think this is possible in African Countries (especially sub-saharan countries) where most people live below the poverty line?

Bill Butz: I do think it is possible. This is something we know how to do, thanks to laboratory science, controlled trials, field experiments and demonstrations, epidemiological studies, and the accumulated experiences of local actions in many places around the developing world. What will it take? Here are a few ideas:

- reduction of agricultural subsidies and trade barriers in the high-income countries, notably Europe and the United States

- direct nutritional intervention programs to supplement micronutrients, fortify foods, and changed dietary behaviors. Community-based health and nutrition programs can work—we know that-—and the successful models should be widely adapted and scaled up.

- continued and accelerated increases in girl’s schooling and women’s status. Research is quite clear that these result directly in improved nutritional status and reduced mortality.

There are other important interventions also. One would be general economic development that benefits poor people. This is also known scientifically to be important, but with the 2015 deadline you gave me, progress on this front would be too slow acting, by itself. Good question!

Adekola Olalekan: If you are told to choose one to focus on, which will you choose? Which is more important? Malnourishment or hunger? This is a case of choosing between quality and quantity.

Bill Butz: Both malnourishment and hunger have multiple dimensions, and their effects differ somewhat depending on the setting. If you tied me down and made me answer your question, though, I would choose malnutrition as more important. Partly, I admit, this is because it is a much clearer thing in terms of concept and measurement, so I know for sure whether what its prevalence is in subpopulations and how the prevalence is changing over time. Hunger is more difficult to define and measure, as evidenced by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences report that made the press last week, recommending, among many other things, that the word “hunger” be replaced in official U.S. government data and reports by phrases that are closer to what is actually measured. Some others would differ with my 1-2 ranking of importance, I bet.

Elba Velasco: Would it be possibly to combine education, with food aid and therefore strengthen the self worth of hungry people? Just giving away food is not enough, it has being proved over and over again

Bill Butz: As we discussed earlier, giving away food is best in famine situations and problematic, at best, in chronic situations. Education is very important, especially for women, who are predominately the persons who have the most influence over access to food and utilization of food in their families. So even apart from strengthening self-worth directly, education contributes to other things like income and empowerment that also contribute to self worth.

Meredith Uttley: The knowledge that so many in the world have so little when dumpsters of food are thrown away daily in the U.S. is so depressing. Is there anything positive to point to?

Bill Butz: There is a great deal positive to point to, Meredith. Despair in the face of success is, in my view, a dangerous phenomenon, because it disregards the lesson that we CAN make things better through directed action. Earlier, I documented the decreases in malnutrition in most developing countries of the world, and the improvements in infant mortality and life expectancy. We should use this information to counter the proposition that “nothing can be done so let’s quit throwing money down a rathole and use it for something that works.” Nonsense! Instead of despair, let us find and document the approaches that have been successful. Let us collect the data and use appropriate statistical and qualitative methodologies to evaluate these successful approaches, including identifying the conditions under which they really work. Let us then adapt them to other places and conditions and, when they are ready which I think many now are, scale them up. The science here is far ahead of information in the hands of decisionmakers and policy makers. Here’s where Population Reference Bureau comes in! Our principal job is to inform people around the world about population, health and the environment, and empower them to use that information to advance the well-being of current and future generations. That is, to narrow this gap between what the data and the research indicate should be done, and what policy and program people are actually doing. Important work.

C. Teller: Can you be more specific about who are the “we” in the question? What are the most policy-relevant groups that could most effectively help? Such as PRB to communicate the issue, private citizen to give money to the most effective NGOs, experts working in this field of hunger and malnutrition who give “pro-bono” advice, humanitarian, research and other speciality organizations, etc. Is there an advocacy group in the US that has clout in the US Congress to mobilize substantial resources to address this continuing scourge of the 21st (esp. in Africa and S. Asia)?

Bill Butz: The “we” in the title of this on-line discussion refers to ALL of us. Your list is a good one and needs no elucidation from me. I’m not going to mention particular U.S. organizations, but I will say clearly that aid (money and technical assistance) from the U.S., other rich countries, and international organizations, for combatting the problems we’re talking about this morning is FAR less that it should be, relative to other purposes of aid, IF RELIEF OF HUMAN SUFFERING AND ITS ECONOMIC EFFECTS IS THE CRITERION. Just as one component, I would emphasize that U.S. foreign aid/assistance to agriculture in developing countries had only very slow increases from 1980 to 92, then fell from 1992-96 and has increased only very slowly thereafter, never coming close to the levels of the 1980s. We’ve already seen this morning the extent that malnutrition contributes to child deaths. Add to that the deleterious effects on disease incidence and outcome in adults (including micronutrient-caused morbidity from vitamin A, iron, and iodine deficiency, and on adults’ work behavior and output (and therefore on national GDP), and the result is a well-documented rate of return on investments in nutrition that surpasses the rates of return on some other prominent (and worthwhile) uses of foreign aid and assistance.

Jennifer Dixon: Hello Bill. Do you think it would be a good idea for the government to mandate for every actor and actress (who are worth millions) to give a percentage of their earnings to a relief fund for the people who are suffering from hunger all around the world?

Bill Butz: Hi Jennifer- Did you know that charitable giving is higher in the U.S. (absolutely and relative to our national income) than in just about any other country? That is also true for charitable giving directed to other countries. So we are a very generous people—more so in our private giving than in our government foreign aid programs, perhaps. As I argued previously, I’d like to see a larger proportion of our charitable giving (by you and me, as well as by wealthy actors) go to combating chronic malnutrition and failed food security. When we give for food, we’re much more likely to do it in response to a natural disaster. That’s important too, but it does little or nothing to improve the longer run problems, and it is they that cause most of the suffering.

Mojisola Eseyin: The issue of hunger is a third world issue. It is particularly that of the children of the world.What role can the developed countries play to facilitate delivery of food at their tables outside what appears to be a fanfare approach via NGOs and funding agencies?

Bill Butz: I hope I’ve already provided some specific answers to your question, Mojisola. I would caution, though, against disparaging the approaches of NGOs and funding agencies. Many of these do excellent work, and cost-effective work. I think that a key to doing better is well-done evaluation studies that point out the approaches that really work. This may be even more important than putting more money in across the board. Evaluation studies of nutrition interventions is a weak area, in my view. More is known methodologically about how to do it than is in common practice. Nutrition interventions and policies are not the only area in which more and more informed investment in evaluation may be the highest pay-off activity of all. Governments and foundations would well consider this in their investment decisions.

Farzana Shahnaz Majid: In my view the poor, illiterate, war affected and people of natural disaster prone country are the most malnourished and hungry. Amongst women are most malnourished, ill health and suffers from morbidity due to extreme poverty specially in the third world then that of men. Women represent a significance of the total population and substantially contributing in the Gross National Product and Gross Domestic product. Do you think that in third world country if we take special measures to eliminate the poverty and malnourishment so the country will be benefitted and people will become nourished.

Bill Butz: The evidence is that, among the factors you list, poverty and illiteracy are is much more widespread causes of malnourishment and hunger than are war and natural disasters. As I keep emphasizing, women, especially women of reproductive age, are key to the puzzle. You’re right to add their contribution to the national economy to the factors I’ve listed in other answers. Poverty and malnourishment are linked in the research, but there are many poor people in the world who are not malnourished, and many malnourished people who are not poor. Lessening poverty is excellent for other reasons, but it has to be said that it would act slowly on a world level to reduce undernutrition, so other directed approaches are also important. (No one’s asked about over-nutrition or obesity, but this is a rapidly growing phenomenon not just in rich countries but in poor ones as well…and with important health and mortality consequences.)

Vanishree: In traditional rural Indian society undernourishment and hunger are closely associated with women. The major cause for this is “women will eat last and least”. The tradition twined with poverty severely affects the health of the women. How this can be challenged?

Bill Butz: Women’s literacy, women’s schooling, women’s status, and women’s rights. We know how to increase each of these. There is absolutely no mystery about it. What’s lacking is getting the science-based information into the hands of policymakers and into the minds of women and men. This information shows clearly the payoffs—economic and otherwise—to making these investments. As Mark Twain wrote, “In legislative bodies [actually, he was more specific than this], the truth is just another lobby.” But it IS a lobby, and if it isn’t there among all the other influences on policy makers, in the form of evidence-based information, surely more productive policies will not come to pass.

Bronke: We see in Countries with a high infant mortality rate that the growth figure is also very high I have mapped it from your statistics. Why are people still saying that too much care for low income people will give only a high population. It is the other way around. Please maybe you can demonstrated this in one of the upcoming bulletins?

Bill Butz: You are exactly correct. We’ll have a look at explicating the strong evidence that underlies your statement in a forthcoming PRB Population Bulletin. Incidentally, I hope you’ll all have a look at our Bulletins, four a year now for decades. You can access them on line, thereby getting up to date quickly on the latest data and research on such a wide variety of important topics on population, health, and the environment.

Veronica Fynn: As an African refugee, I have been fortunate to not only experience poverty and hunger to the maximum but also see the blatant waste characterized by Western cultures (especially in USA). In my daily pursuit to return to my people and my culture I always find huge challenges and road blocks in the form of discrimination, lack of privilege and opportunities to excel. I know in my heart of hearts I can effectively contribute to positive change on the continent given my educational qualification and unparallel real life experiences. In my struggles I have realized that education seems to be the one significant factor that can bring immense change to anyone’s life but of course not in isolation. So, my question is how can we (on behalf of poor and hungry African refugee children) penetrate the diplomatic, profit-driven Western society in order to give something back to our people? How could we (African youths) be given the opportunity to get involve in Africa’s political system with security and peace? I believe, in as much as outsider can contribute to changing the situation in Africa, Africans with unique experiences are also capable of effecting far better change on the continent as well. Too many innocent children are dying each day just for lack of care and provision of life’s necessities–food, water, peace and happiness.

Bill Butz: How can a single person, particularly an African, make a contribution to this bewilderingly complicated problem? The answer I believe most passionately in is to find—for yourself, for each of us—where the world’s needs intersect with your passions…and then prepare to work or to contribute your time or money charitably in that intersection! Is it local action? Is it scientific research? Is it persuasion of others, including policy makers, to take these problems seriously? It is becoming so interested in politics that you, yourself, become active in your country’s organized political system. Each of these and all the other possible intersections imply particular preparation on your part. So first, where’s your passion. Second, prepare. Third, act. Others may disagree, but for me, I think this is the path…and that we’ll get there.

Patrick Rea: Given the fact that a countries growth rate, fertility ratio, % of the population under 15, literacy rate, cultural and religious opposition to birth control, adverse environmental conditions, and political discontent are major factors contributing to malnourishment, how can the United States be a more effective benefactor when addressing the issue of world hunger?

Bill Butz: I suggest that the U.S. and other “donor” countries pay more attention to sustained effort to combat chronic malnutrition, hunger and food insecurity, rather than expending so much of our political reserves and good will reserves on crisis situations and then forgetting about it.

Dianne Holcomb: The USDA recently changed the language in the USDA Food Security Survey tool, eliminating the word “hunger” in describing people, i.e., “food insecure with hunger” to “very low food security”. This poses an increased challenge to those of us whose work is to educate the public that there is an overwhelming and increasing number of Americans who are HUNGRY. This makes our jobs as advocates even more difficult, and further marginalizes American citizens who are in crisis. At the same time, feeding program usage in the U.S. is increasing. What more can we do to achieve systemic change to end hunger in our country and how can we prioritize this as a national goal?

Bill Butz: I would personally pay less attention to the change in terminology, which was after all a science-based recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences. Hunger and undernutrition in the US are strongly associated with poverty and with poor food-related knowledge and practice. Overnutrition in the US is also associated with those same two factors, strangely enough. Teaching parents, again especially mothers and other women of childbearing age, the dire consequences of mal (both under- and over-) nutrition of their children and teaching them how their kids can eat more properly is an important part of the answer. Research is clear on this. Well, time for me to sign off. What excellent questions…and so many more that must go unanswered! I am encouraged by all of your concerns and the intelligence of what you ask and say. I apologize if I have not gotten to your particular question or comment!

Mike Sage: I read both the questions and answers will hope but no one seems to ask the question which is on the mind of most environmental scientist, and that is there are just too many people on the planet to remain sustainable in it’s resources. Without education for all, this challenge will only become a greater danger to all that live here. Scientific progress takes time, implementation adds to this slow forward movement but the population continues to move higher each year. What have we done to reduce what is considered the world’s number one problem?

Bill Butz: Thanks for bringing this important consideration in, Mike. This is one of the areas I referred to earlier where there has been substantial success that we should recognize and use to propel forward the investments that have led to the success. The success is that fertility rates in virtually every country of the world are now falling. The US is one of the few exceptions) Nevertheless, world fertility will continue to grow for likely a half century because of the momentum of high (although falling) fertility rates in many countries, along with the large numbers of women of childbearing ages due to past high fertility. So…what has caused these fertility declines. Science has firmly identified four causal factors:

- Declining mortality rates. These cause more people to live to adulthood so that couples need fewer births to produce the same number of offspring to help in agricultural and housework and to care for them in old age.

- Increasing literacy, schooling and status of women. This tends to lower desired family size, give women increased opportunities to do things other than raise children, and increase their influence in the family and the community.

- Increasing the income of poor people. As people’s income increases from low levels, they have fewer births, a nearly universal pattern.

- Providing access to modern contraceptives and information about them. This enables women and couples to attain the lower fertility they desire as factors 1, 2, and 3 operate.

How now to sustain the fertility declines and hasten the day when they world’s population will no longer grow? It’s easy to say: Continue and expand these same four factors. If we do not do this, there is no reason to expect, based on the past half century’s evidence, that fertility rates will continue to fall in the now poor countries. If we do, this same evidence is convincing that fertility rates will continue falling.

Bye to all!

HIV/AIDS and the Natural Environment

Date

December 2, 2006

Author

Lori M. Hunter

University of Colorado, Boulder

Still, at least one research and policy dimension remains little explored: The relationship between HIV/AIDS and the natural environment. HIV/AIDS is shaping society’s impact on the natural environment in myriad ways and at many levels.

This intersection of HIV/AIDS and the environment will affect millions of people, particularly in rural areas of developing countries.

Shaping Individual Vulnerability

Local natural resources are an important means of sustenance and income-generation in many rural areas of developing countries. The health of the local environment can also shape individual vulnerability to HIV/AIDS in at least two ways. First, resource scarcity often deepens poverty in natural resource-dependent regions, as in much of rural sub-Saharan Africa. Research has demonstrated that desperate economic circumstances can heighten the risk of HIV infection by leading individuals, particularly women and girls, to engage in “transactional sex” for material goods, sometimes to meet daily sustenance needs.1 Studies in Africa reveal that when such “Sugar Daddy” relationships involve large age differences or a substantial amount of assistance, women are more likely to engage in unsafe sex.2 Although transactional sex has not yet been linked to environmental context directly, local resource scarcity and risky sex are both clearly associated with a strong intermediary: poverty.

Second, natural resource scarcity may lead to food insecurity and inadequate diet, which can further undermine the immune system of HIV-infected people. Malnutrition increases the susceptibility of HIV-infected persons to opportunistic infections, while also increasing the risk of HIV transmission from mother to baby.3 Research in Singapore suggests that malnutrition may also reduce the effectiveness of HIV/AIDS treatments.4

Undercutting Household Resilience

The age profile of people dying from AIDS shapes the pandemic’s effects at the household level. In developing countries, AIDS deaths are concentrated in prime working ages—particularly the 25-to-45 age group—and the loss of a productive household member can be especially devastating to households already living in poverty.

Natural resources available through the local environment can act as a buffer against these losses. In rural South Africa, for example, households in which family members have died are more likely to gather wild foods from the bush than households without recent deaths.5 The specific household-level impacts often vary with the role of the deceased in the household, particularly whether the individual brought in income or gathered resources from the countryside. If the deceased collected resources, for example, but did not work for wages, other household members typically take on their resource-harvesting duties. In rural South Africa, children often take on these collector duties after school.6 In Kenya, such a reallocation of labor often means that children must drop out of school entirely, especially in poor households.7 If the deceased had contributed wages to the household, harvesting natural resources may substitute for previously purchased goods. For example, rural households suffering the loss of income because of an AIDS death might collect wild protein-rich foods to substitute for the meat they had previously been able to purchase. As a recently widowed woman in rural South Africa noted: “Locusts are now our beef,” when describing how her household’s diet had changed since the loss of her husband’s income.8

HIV/AIDS also shapes household use of the local environment when it deprives families of the labor performed by household members who are disabled or die from the disease. Labor shortages are also exacerbated as caregivers are drawn away from typical household duties. These various constraints may shape decisions about the use of land resources, a key component of rural livelihoods in many developing regions. Evidence of these associations was demonstrated in a three-country study by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), which found that agricultural productivity declined in AIDS-affected households. In Kenya, for example, AIDS-affected households cultivated less area because less labor was available. In South Africa, AIDS-affected households failed to weed their cultivated plots, which also reduced agricultural productivity.9

Even basic access to land may be lost because of HIV/AIDS illness and death, particularly in regions where women and children have access to land only through their husbands and fathers. In Kenya, the death of a male household head may cause women and children to lose possession of land rights because inheritance is patriarchal. Land is inherited or held in trust by male relatives, threatening access of female relatives to this essential component of rural livelihoods.10

Local natural resources not only serve dietary needs, but are often used for energy as well. Additional evidence from South Africa suggests that impoverished households affected by adult mortality are more likely than other households to use fuelwood rather than electricity or paraffin for cooking. Such intensified resource dependence can increase local environmental degradation, particularly in areas already overharvested.11

HIV/AIDS, Communities, and Natural Resource Management

The age profile and the sheer magnitude of the HIV/AIDS pandemic suggest that the pandemic exerts environmental impacts at the community level also. There are many possible pathways for the HIV and environment interaction, although little empirical evidence of this exists so far. One way HIV/AIDS affects the community is through the loss of crucial human capital. Resource management institutions and organizations suffer as knowledge and labor are lost with the death of prime-age adults. A second avenue for community impact is through the loss of traditional knowledge regarding cropping and other resource use when experienced farmers die. Still, as argued by Thomas Jayne, Professor of International Development at Michigan State University, “the longer-term effects, particularly the community-level effects, have yet to be measured” because of a lack of longitudinal data and other methodological limitations.12

Links Between Public Health and Environmental Policy

Although operating at multiple levels and in many ways, the environmental dimensions of HIV/AIDS have received little attention in the policy arena. Few bridges exist between public health and environmental dialogue and policymaking, as evidenced by the lack of discussion of this intersection at the 2006 HIV/AIDS conference in Toronto. At the conference, the natural environment found a place on the program primarily within the context of food security. Although clearly a critical topic, food security is but one of many dimensions of the pandemic’s effect on the natural environment.

Recognizing the associations between HIV/AIDS and the natural environment can contribute to the well-being of both human populations and local environments, particularly in regions characterized by high prevalence of HIV/AIDS and natural resource dependence and scarcity.

Because environmental scarcity can heighten HIV/AIDS vulnerability, environmental policy encouraging sustainable use of local environments can also benefit public health. This is especially true in regions where resource scarcity deepens poverty and robs households of viable livelihood options. In addition, health interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS vulnerability can produce environmental gains, particularly in areas characterized by high levels of resource dependence and where pressure on local resources is intensified by adult mortality. In this region, reduced mortality may lessen environmental pressure by reducing dependence on local natural resources such as fuelwood for cooking.

Because poverty is a driving force in the vulnerability to both HIV/AIDS and unsustainable resource use, poverty reduction efforts could yield substantial gains in both public health and environmental protection. One program recognizing these critical links is the Umzi Wethu Training Academy for Displaced Youth in Eastern Cape, South Africa. A project of the Wilderness Foundation South Africa, the program offers certified vocational training and internships to AIDS orphans and vulnerable youth, helping them qualify for well-paid local conservation jobs. Although the tourism industry has been hard-hit by the loss of employees to AIDS, ecotourism has been increasing 10 percent annually in the region, expanding opportunities for game rangers, hospitality hosts, and other tourism service providers. Enhancing opportunities for local at-risk youth not only helps the local economy, but reduces the likelihood they will engage in risky sexual behavior. These poverty reduction efforts therefore lessen the spread of HIV/AIDS as well as protect natural resources.

Although research on the HIV/AIDS and environment intersection is in its infancy, the early evidence suggests that the public health, HIV/AIDS, and environmental policy and advocacy communities would gain strength by recognizing the overlaps in their agendas. The Umzi Wethu Training Academy has been designed with such overlaps in mind and represents the type of integrated approach to program and policy development that warrants serious consideration.

Lori Hunter is a Bixby Visiting Scholar at the Population Reference Bureau, and associate professor of sociology and environmental studies at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

References

- Kristin L. Dunkle et al., “Transactional Sex Among Women in Soweto, South Africa: Prevalence, Risk Factors and Association With HIV Infection,” Social Science & Medicine 59, no. 8 (2004): 1581-92; Mark Hunter, “The Materiality of Everyday Sex: Thinking Beyond ‘Prostitution,’ ” African Studies 61, no. 1 (2002): 99-120; and Simon Gregson et al., “Sexual Mixing Patterns and Sex Differentials in Teenage Exposure to HIV Infection in Rural Zimbabwe,” Lancet 359, no. 9321 (2002): 1896–1903.

- Gregson et al., “Sexual Mixing Patterns and Sex Differentials”; and Robert J. Kelly et al., “Age Differences in Sexual Partners and Risk of HIV-1 Infection in Rural Uganda,” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 32, no 4 (2003): 446–51.

- An overview of research in this area is provided by E.G. Piwoz and E.A. Preble, HIV/AIDS and Nutrition: A Review of the Literature and Recommendations for Nutritional Care and Support in Sub-Saharan Africa (Washington, DC: Support for Analysis and Research in Africa (SARA) Project, U.S. Agency for International Development, 2000).

- Nicholas I. Paton et al., “The Impact of Malnutrition on Survival and the CD4 Count Response in HIV-Infected Patients Starting Antiretroviral Therapy,” HIV Medicine 7, no. 5 (2006): 323-30.

- Lori M. Hunter, Wayne Twine, and Aaron S. Johnson, “The Role of Natural Resources in Coping With Household Mortality: An Examination in Rural South Africa,” Working Paper EB2005-0004 (Boulder, CO: University of Colorado at Boulder, Institute of Behavioral Science, 2005), accessed online at www.colorado.edu/ibs/, on Nov. 13, 2006.

- Hunter, Twine, and Johnson, “The Role of Natural Resources in Coping With Household Mortality.”

- Takashi Yamano and Thomas S. Jayne, “Measuring the Impacts of Working-Age Adult Mortality on Small-Scale Farm Households in Kenya,” World Development, 32, no. 1 (2004): 91-119

- Lori M. Hunter, Wayne Twine, and Laura Patterson, ” ‘Locusts Are Now Our Beef’: Adult Mortality and Household Dietary Use of the Local Environment in Rural South Africa,” Working Paper EB2004-0005 (Boulder, CO: University of Colorado at Boulder, Program on Environment and Society, 2004), accessed online at www.colorado.edu/ibs/, on Nov. 13, 2006.

- Scott Drimie, “HIV/AIDS and Land: Case Studies from Kenya, Lesotho and South Africa,” Development Southern Africa 20, no. 5 (2003): 647-58.

- Drimie, “HIV/AIDS and Land.”

- Hunter, Twine, and Johnson, “The Role of Natural Resources in Coping With Household Mortality.”

- Thomas S. Jayne et al., “Community-level Impacts of AIDS-Related Mortality: Panel Survey Evidence from Zambia,” Review of Agricultural Economics 28, no. 3 (2006): 440-57.

HIV/AIDS

View All

Feminization of Migration

This is the first in a series of articles on the feminization of migration. Support for this series is provided by the Fred H. Bixby Foundation.

(December 2006) There has been a change in the international migration patterns of women: More are moving from one country to another on their own, rather than to join their husbands or other family members. This feminization of migration raises several key policy concerns about women’s security and human rights in sending and destination countries.1 International analysts have increasingly focused on these changes and their implications, but they have been neglected in the popular debate about immigration, and myths persist about why women migrate.

Discussions of migration have more often emphasized its causes than reflected on who is migrating. Conventional wisdom has been that more men migrate voluntarily, while the vast majority of refugees and displaced persons are female. Yet recent analysis shows that about half the people who live in some other country than the one in which they were born are female.

As international migration has increased steadily over the past 40 years, the percentage of migrants who are female has not risen as much. In 1980, 47 percent of international migrants were female. In 2000, 49 percent were.2 The global picture does, however, hide some dramatic differences at the country level. For example, as a result of the changing labor market for domestic work in other Asian countries and the Middle East, the percentage of female migrants leaving the Philippines has increased dramatically. Female migrant labor is now the country’s largest export.3

What has changed more dramatically than the numbers are the reasons why females migrate. In 1960, more women were classified as dependents, whether or not they were financially independent, and moved for family reunification purposes. Today, a higher percentage leaves for economic opportunities.4 Of course, not all migration is voluntary: Millions are forced to move due to war, civil unrest or coercion, an issue the global community has been working to address. And even for some voluntary migrants—particularly females—conditions are not always positive. Some migrants, disempowered by poverty, or discriminated against by ethnicity or sex, may be exploited or trafficked.

Adopting a gender perspective is important to understanding the positive and negative impacts of the feminization of migration. This article, the first in a series about the feminization of international migration, looks at three key topics through the prism of gender.

Productive and Reproductive Work

Gender specialists make a distinction between productive work, that is, employment that earns income for specific output in the formal or informal economy, and reproductive work, consisting of daily tasks such as cooking, cleaning, and child care that are necessary to keep a household functioning. In this context, “reproductive work” does not refer to biological reproduction, but more to day-to-day household maintenance.

This distinction helps focus a gender lens on international migration. Women are often recruited internationally to do reproductive work in other people’s houses or for service-sector jobs such as waitressing or entertainment that are poorly paid and marked by high instability and turnover. Many of these jobs are unregulated because they are of borderline legality (such as sex work) or because they are not included in the scope of the destination country’s labor laws, which primarily cover productive work. The unregulated nature of reproductive work, which allows no recourse through the legal system, places many women migrants at risk of exploitation in the form of low wages, poor working conditions, or physical or sexual abuse.

The migration of women to do reproductive work in other countries extends the definition of such work beyond their own households. In many cases, changing employment opportunities for women in developed countries created income-earning opportunities for women from developing ones. For example, as female education levels rose in Singapore in the 1980s, more local women began to do productive work outside the home. This shift opened up opportunities for women from the Philippines to fill positions as domestic workers and care-givers in Singaporean homes.5 Thousands of Asian female household workers migrated to the oil-rich countries in the 1980s and 1990s. This, along with the declining need for male construction workers, propelled a shift in the ratio of Asian female and male migrants.

Increasingly, women who migrate from poor countries to carry out reproductive work in the households of wealthier countries participate in a global care chain as they become members of transnational families. Many female migrants have their own children and elders to look after. Usually, they either pass on this responsibility to other female relatives—or, with their higher foreign earnings, hire lower income domestic workers to manage their own households. This can create families whose members belong to two households, two cultures and two economies simultaneously. This can serve to change the head of household, as grandmothers or youth take charge of children with absent parents, and create conflicting national loyalties.6

Financial and Social Remittances

Remittances can refer to money sent home, but also to the new ideas and patterns of behavior that migrants convey. Financial remittances are substantial: In 2005, migrants are estimated to have sent home more than $233 billion worldwide, of which $167 billion went to developing countries.7 There are gender differences in remittance patterns. Overall, men remit more than women because they earn more, though women tend to remit a larger portion of their earnings.

Migrants transfer funds through a variety of means, including checks, cash, money orders, electronic transfers, the postal system, banks, credit unions, small and large money transfer companies, and couriers. They also carry funds home themselves, or use less regulated or informal mechanisms. Women who remit funds home often rely on the less formal means, in part because they lack the education ort experience to use the formal banking system. Since informal methods often involve higher fees or other transaction costs, women’s remittances may lose more value during the process.8

There also may be differences in the uses of men’s and women’s remittances, an intriguing possibility that deserves further research. Migrant women tend to remit a large portion of their salaries for everyday needs, in support of household maintenance. Men may tend to remit more for investment, such as buying land, a farm, housing, farm machinery or cattle.9

Migrant women and men also send or take home “social remittances” in the form of new skills, attitudes, and knowledge that can lead to new gender norms. The social remittances of migrant women can boost socioeconomic development in their home countries, improve women’s health, and promote human rights and gender equality. The social remittances men convey include adopting behavior they observed in other countries, such as choosing their own spouses and doing more of women’s traditional work, including childcare.10

Human Trafficking

Forced international migration and exploitation—human trafficking—is an enormous problem and a lucrative business. The U.S. government estimates that between 800,000 and 900,000 people become victims each year. Most are young women. Human trafficking is a particular problem in Asia because of the large migration of workers into unregulated household and entertainment employment, and in the former Soviet Union or Eastern Bloc countries, where prostitution is the main cause.11

Over the past five years, the world community has begun to turn its attention to the issue of human trafficking, which people are vulnerable to through lack of opportunity. In some regions, traffickers obtain their victims by abducting them. But more often, they find their victims among people who want to migrate. Gender discrimination, income inequality, and lack of opportunity fuel this desire.

Victims also may have an ill-informed vision of jobs, money, marriage, and success in destination countries, which traffickers exploit for their own gain. Women may be more likely to respond to the traffickers’ propositions because they generally have less education and knowledge of formal legal systems than men. In addition to kidnapping, four other common methods have been identified that specifically are used to traffic women. They include the pretext of an offer of employment without sex industry connotations; pretext of an offer of marriage; pretext of an offer to be a singer or dancer in the entertainment industry; and deception about conditions in which a woman will undertake prostitution.12

Human trafficking is a large and persistent problem because traffickers make vast amounts of money: Approximately $8 billion a year, nearly what is made trafficking drugs.

Nancy V. Yinger was director of International Programs at the Population Reference Bureau from January 2000 to June 2006.

References

- International Organization for Migration (IOM), International Migration Law: Glossary on Migration (Geneva: IOM, 2004).

- Hania Zlotnik, “Global Dimensions of Female Migration,” Migration Policy Institute, 2003, accessed online at www.migrationinformation.org, on Dec. 1, 2006.

- Lauren B. Engle, The World in Motion: Short Essays on Migration and Gender (Geneva: IOM, 2004).

- IOM, International Migration Law: Glossary on Migration.

- Engle, The World in Motion: Short Essays on Migration and Gender.

- UNFPA, The UNFPA State of the World Population 2006 (New York: UNFPA, 2006).

- UNFPA, The UNFPA State of the World Population 2006.

- Engle, The World in Motion: Short Essays on Migration and Gender.

- UNFPA, The UNFPA State of the World Population 2006.

- UNFPA, The UNFPA State of the World Population 2006.

- Engle, The World in Motion: Short Essays on Migration and Gender.

- Analysis of Institutional and Legal Framework and Overview of Cooperation in the Field of Counter-trafficking in Eastern Europe and Central Asia (Vienna: IOM, 2003).

Strategies for Sustainable Development: Case Studies of Community-Based Population, Health, and Environment Projects

Date

October 18, 2006

Author

PRB

(October 2006) PRB, in partnership with nongovernmental organizations in the Philippines, has produced five case studies that document approaches to the implementation of integrated population, health, and environment (PHE) projects. Written by the project managers themselves, the case studies provide lessons learned from their experiences, and focus on issues such as partnering with local governments, engaging communities in participatory research, and developing advocacy strategies. See the table below for a synopsis of each case study and the key issues they address.

The interactive nature of the case studies, which include discussion questions, makes them ideal for use in a classroom or workshop setting (see information on the Teaching Guide below). Outside of a workshop setting, development practitioners and others who read the case studies independently may find new inspiration and ideas for their own work.

PHE Case Studies at a Glance

Strategies for Sustainable Development: Case Studies of Community-Based Population, Health, and Environment Projects

|

Case Study

|

Synopsis

|

Key Issues

|

|---|---|---|

| From Roadblock to Champion: PHE Advocacy and Local Government Executives by Enrique Hernandez, PATH Foundation Philippines, Inc. | In many places around the world, local government executives (mayors, chiefs, and governors) have decisionmaking authority that could significantly affect the content and direction of development projects. This case study relates the story of how a development NGO—PATH Foundation Philippines, Inc. (PFPI)—won the support of a mayor who almost derailed an innovative project in her municipality that was working to incorporate reproductive health interventions into coastal resource management plans. | Advocacy strategies, role of local government executives, partnerships, coastal resource management, food security |

| Identifying Our Own Problems: Working With Communities for Participatory PHE Research by Rainera L. Lucero, World Neighbors | Determining the most important development challenges at the community level can be difficult, especially when they entail complex cause-and-effect relationships across different sectors. This case study relates the story of how World Neighbors (a development NGO) involved community members in identifying both critical development challenges and the relationships among those challenges in their community. World Neighbors then supported a process through which the community members developed a plan of action to achieve their goals in the areas of livelihoods, natural-resource management, and reproductive health. | Participatory research/community engagement, volunteer recruitment and retention, cross-sectoral planning, adolescent reproductive health, agriculture, migration |

| Building Partnerships With Local Government Units: PHE Programming in the Municipality of Concepcion by Norma Chan-Pongan, Save the Children U.S.– Philippines Country Office | The sustainability of development programs is a major concern for many NGOs involved in program design and implementation. This case study tells how Save the Children (or SC, a development NGO) established a successful partnership with a local government unit (or LGU, in this case, the municipality of Concepcion) to ensure that integrated PHE programming would be sustained and mainstreamed into local government activities after SC’s involvement ended. | Partnerships, engagement of local government, project sustainability, community outreach, poverty alleviation |

| Enlisting Organizational Support for PHE: Perspectives From a Microfinance Institution by Ellen Grace Z. Gallares, First Consolidated Bank Foundation, Inc. | Enlisting organizational support for a new concept or innovative idea can be a daunting challenge. This case study relates the story of how decisionmakers at the First Consolidated Bank Foundation, Inc. (FCBFI), a nonprofit microfinance institution, evolved from being skeptical to cautiously optimistic about innovative approaches to social development and pro-poor lending—including integrating PHE concerns into the foundation’s programs. | Organizational change, message formulation, mission drift, microfinance |

| Fhaida’s Journey: Promoting Population, Health, and Environment Interventions in a Muslim Community by Jumelita Romero, Tawi-Tawi Marine Research and Development Foundation, and Jurma Tikmasan, Tarbilang Foundation | Development practitioners must often invent strategies to work within constraints posed by traditional and cultural beliefs that may affect the progress of community projects. This case study is a fictional story that synthesizes many of the challenges and obstacles that two actual development NGOs—the Tawi-Tawi Marine Research and Development Foundation and the Tarbilang Foundation—faced in mobilizing women to address PHE issues. The story demonstrates strategies that were used to advocate change while also respecting the religious values of a Muslim community in the Philippines. While the events of this case study occur in a Muslim religious and cultural setting, the lessons the case study contains may be usefully applied in a variety of settings. | Advocacy strategies, religious and cultural barriers, gender roles |

Strategies for Sustainable Development Teaching Guide

Trainers and others who would like to use the case studies to facilitate group discussion of the issues addressed in the case studies may wish to download the Teaching Guide, which provides general suggestions for effective facilitation, proposed agendas for workshops of differing lengths, and specific insights on each of the case studies that will help facilitators highlight key learning points. The Teaching Guide includes the following components:

- Overview: What Are Teaching Case Studies, and Why Use Them? (PDF: 429KB)

- Tips for Facilitating PHE Case Studies (PDF: 450KB)

- Sample Workshop Agendas (PDF: 450KB)

- Teaching Note for “From Roadblock to Champion: PHE Advocacy and Local Government Executives” (PDF: 470KB)

- Teaching Note for “Identifying Our Own Problems: Working With Communities for Participatory PHE Research” (PDF: 470KB)

- Teaching Note for “Building Partnerships with Local Government Units: PHE Programming in the Municipality of Concepcion” (PDF: 468KB)

- Teaching Note for “Enlisting Organizational Support for PHE: Perspectives From a Microfinance Institution” (PDF: 464KB)

- Teaching Note for “Fhaida’s Journey: Promoting Population, Health, and Environment Interventions in a Muslim Community” (PDF: 468KB)

- Download entire Teaching Guide (PDF: 805KB)

These case studies were produced by PRB’s Population, Health, and Environment Program, with support from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

Families, Fathers, and Demographic Change

(October 2006) Two important demographic trends have reshaped the typical person’s life dramatically over the past century: Increasing longevity and the shrinking number of children per family. Husbands and wives, as well as fathers, mothers, and children, now spend more years in each other’s company, creating opportunities as well as challenges.

This change has profound implications for relationships between parents and their adult children, as well as between men and women. Because parents live longer and children are more likely to survive into adulthood, they now spend most of their years together when both generations are adults.

These trends are changing the ways these groups relate to each other—in ways that made sense when few parents lived long enough for their children to become adults and when husbands and wives had few years when they were not actively caring for children. The greatest impact of this may well be on fathers.

The twin demographic changes mean that far fewer people lose their parents during childhood, which serves to prolong intergenerational relationships during adulthood. Many people express concern that increased survivorship means more years of caring for elderly parents, though most elderly parents are in good health and most of their “new” years are healthy ones. And though women could spend their “extra” years caring for more children, they have been having fewer children than in the past.

The table below shows that, contrary to what many assume, the gains in women’s lifespan are not due mainly to reductions in infant and child mortality. In fact, nearly half the increase comes in adulthood.

‘New’ Years Gained by Women Worldwide, 1900-2000

| Increased life expectancy at birth |

30 years

|

| Increased life expectancy at age 15 |

15 years

|

| Increased life expectancy at age 45 |

10 years

|

| Increased life expectancy at age 65 |

7 years

|

Source: S. Watkins, J. Menken, and J. Bongaarts, “Demographic Foundations of Family Change,” American Sociological Review 52, no. 3 (1987): 346-58.

The first challenge is in restructuring adults’ relationships with the children they do have, during new years that mainly take place when the children are adults. For example, inheriting a family farm or business is much less straightforward, as the older generation often is unwilling or unable to retire when the children are of age. Consider the problem of Prince Charles, crown prince of the United Kingdom. His mother is continuing to reign at the age of 80, while her son has reached late middle age.

But for the vast majority of parents and their adult children, the big challenge is hierarchy. Should parents continue to treat their children as children when they are adults? Should middle-aged adults continue to treat their parents as key authority figures? If they do so, it will be a detriment to the relationship and increase the distance between them. Their relationship would be more rewarding if they each could treat the other as respected, close kin.

If it is difficult for a child to have an “adult” relationship with a parent, and for parents to let go of power, the challenges of adapting are even greater for male-female relationships. How does demographic change affect the “old deal” that he support her and their children throughout their lives, which are much longer now? Only a single transformation is required in relationships between parents and adult children as they grow older, but there are three transformations necessary in male-female relationships, which serve to rebalance their activities and often relative power.

When the first child is born, the couple’s similar roles as students or, increasingly, workers, diverge as his responsibility for support increases along with hers for care. As children become more independent, she undergoes a “phased retirement” from parenting toward the empty nest. Then, when he retires, he leaves employment to enter her world at home.

Male and female roles used to be more similar in both spheres. Until the late 1800s, most people lived agricultural lives. Three-quarters of men were engaged in farm activities, and presumably nearly all of their wives were, too. Their productive activities were joint. They were not equal: Men owned their wives’ person in common law and normally owned the land as well. Nevertheless, their daily reality was likely less shaped by these factors than by their own personalities and by the crises large and small that they faced as they worked together to provide for their family and care for their children.

The gender division emerged as the 19th century rolled on. More men left agriculture to find jobs in the nation’s expanding manufacturing and service sectors. By 1890, most men were employed in the public sphere. Most women remained in the private one, and growing numbers were becoming the new “housewives” with a purely domestic focus.

The gap between men’s and women’s lives increased to its maximum between 1890 and 1950, before the great increase in women’s nonagricultural, paid employment. The partnership of the farm faded from memory. Hence, when the same forces that led men to more productive modes of family support began to work on women as well after 1950, it seemed to be something totally new, totally alien.

The transformations in women’s economic lives closely resemble those that took place in men’s 100 years earlier. But what will happen to the family? Can men and women regain the notions that they can both be economically productive, as they were in the farm family, and both contribute to raising children? Or have the home and norms and values that domestic women reconstructed over a century become such a foreign place to men that fatherhood will remain a status, but not again an active role?

The question that has dominated for the past half century has been the relationship between work and family for women. Men’s role in domestic work was almost entirely ignored. Margaret Mead, for example, imagined that de facto three sexes were emerging: Working women such as herself, domestic women in the role she had spurned, and men, who, of course, were workers.

Women need men to share in the care of children if they are to become equal in the workplace. It often seems, however, that many are unwilling to share this responsibility, as the growing “gate-keeping” literature attests. As men kept women away from the family car for so many decades, so, too, are women finding ways to convince men that they are incompetent parents.

Moreover, other barriers have arisen. The rise in divorce makes parenthood very different for men, as the presumption of female custody forces many men to be absent fathers and many others to become stepfathers. The demographic transition of longer lives and smaller families, intertwined with the industrial revolution, has made equality both more and less likely. Ideally, emerging nations that experience both at the same time will have an easier path.

Frances Goldscheider is professor of sociology, emerita, at Brown University; and College Park professor of family studies at the University of Maryland.

References

Sarah Allen and Alan Hawkins, “Maternal Gatekeeping: Mothers’ Beliefs and Behaviors That Inhibit Greater Father Involvement in Family Work, Journal of Marriage and Family 61, no. 1 (1999): 199-212.

Eileen Crimmins et al., “Changing Mortality and Morbidity Rates and Health Status and Life Expectancy of the Older Population,” Demography 31, no. 1 (1994): 159-75.

Claudia Goldin, Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

Donald Hernandez, Children (New York: Russell Sage Foundation Census Monograph Series, 1993).

Ralph LaRossa, The Modernization of Fatherhood (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

Glenna Matthews, Just a Housewife: The Rise and Fall of Domesticity in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987).

Susan Watkins, Jane Menken, and John Bongaarts, “Demographic Foundations of Family Change,” American Sociological Review 52, no. 3 (1987): 346-58.

Barbara Welter, “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860,” American Quarterly 18, no. 2 (Summer 1966): 151-74.

Laura Ingalls Wilder, “Why Marry a Farmer?” Redbook, 1915.

U.S. Sports Teams: Demographic Changes Expand Franchises

(October 2006) As the population of the United States grew from 200 million to 300 million from 1967 to 2006, some fast-growing major metropolitan areas scored big time in the major league sports arena. Phoenix went from zero to four major sports teams. Tampa-St. Petersburg sports fans had something to cheer about too: the arrival of three major sports franchises, up from zero. And sports buffs in Dallas-Fort Worth can now root for four major local teams, up from one.

These major metro areas are among the 30 that added major sports franchises between 1967 and 2006. Of those, 17 acquired their first major sports team after 1967.

The expansion of professional franchises in Major League Baseball (MLB), the National Football League (NFL), the National Basketball Association (NBA), and the National Hockey League (NHL) reflects the shift of population from the Northeast and Midwest to the South and West over the past few decades. (The 1967 data for professional sports teams include the American Football League, which merged with the National Football League in 1970.) The share of U.S. population that lived in the Northeast and Midwest dropped from 52 percent to 41 percent between 1967 and 2005. The South and West now account for nearly 60 percent of the population. And the West, which was the least populous of the four U.S. regions in 1967, has now surpassed the Northeast and Midwest in population.

In the fall of 1967, the four leagues contained 67 U.S.-based franchises. Nearly two-thirds (41) were in the Northeast and Midwest. And 18 of the 26 sports teams in the South and West did not exist (at least in their 1967 locales) before 1960.

The situation in the fall of 2006 tells a much different story. Thanks to expansion in the four major leagues, the number of U.S.-based franchises grew to 114. And the South and West have been the main beneficiaries of the post-1967 expansion. While those two regions boasted just over one-third of U.S.-based franchises 39 years ago, they account for more than half (63) today. In the South alone, the number of professional sports franchises has nearly tripled, from 12 to 35. The number of ice hockey teams in the South rose from zero to seven. They include the Atlanta Thrashers, Carolina Hurricanes (Raleigh), Dallas Stars, Florida Panthers (Miami), Nashville Predators, Tampa Bay Lightning, and Washington (DC) Capitals.

One key factor in this sports expansion is the emergence of new economic markets. For example, of the 42 metropolitan areas that have at least one major league team, 40 had populations of at least 1 million and were among the 50 largest metros in 2005. (And Raleigh, N.C., one of the other two, ranked 51st with a population of 950,000.) This is a continuing phenomenon. In 1967, 24 of the 25 metros with at least one major franchise had populations greater than 1 million.

Many of the post-1967 major league metros grew rapidly between 1967 and 2005. As a group, these 17 “expansion” metropolitan areas grew 140 percent during that period, more than double the 53 percent increase for the 25 pre-1967 metros. Four of the expansion metros—Orlando, Raleigh, Phoenix, and Charlotte—have at least quadrupled their populations since 1967. By contrast, 12 of the 13 major league metros that increased by less than 40 percent already had at least one major sports franchise in 1967. And the one exception, Milwaukee, had lost its major league franchise, the MLB Braves, after the 1965 season, and were without a major sports team until the NBA Bucks began play in the fall of 1968.

Even the metros that already had at least one major team in 1967 did not grow at the same rate. Among the “pre-1967” major league metros, the ones that have enjoyed the most rapid growth over the past four decades were those that added their first major league sports teams in 1960 or later. These include metros such as Atlanta (MLB Braves and NFL Falcons, 1966), Miami-Fort Lauderdale (NFL Dolphins, 1966), Houston (MLB Astros, formerly the Colt-.45s, 1962), and Dallas-Fort Worth (NFL Cowboys, 1960). All four of the above metros have grown more than 175 percent since 1967. By contrast, the pre-1967 metros that already had a major team in 1959 have grown slower, just 32 percent in the last four decades.

Rapidly growing metros tended to attract multiple major league franchises. Since 1967, 13 metropolitan areas including not only Atlanta, Phoenix, and Dallas-Fort Worth, but also New York and Washington, D.C. have added at least two major league franchises since 1967. As a group, these metros grew 87 percent during this period, much faster than the 31 percent increase for the 12 metros that have the same number of major league franchises today as they did in 1967.

Population growth is by no means the sole determinant in sports expansion. Economic considerations such as stadium revenues and costs, television deals, and agreements with local governments are even more important. But like any business, professional sports leagues and their teams need a strong consumer base. As they seek new fans, they will always look to emerging new markets.

So it wouldn’t be surprising if MLB, NFL, NBA, or NHL expands to such fast-growing areas as Las Vegas or Austin in the next 40 years as the U.S. moves toward a population of 400 million.

Kelvin Pollard is a senior demographer at the Population Reference Bureau.

Lifestyle Choices Affect U.S. Impact on the Environment

Date

October 2, 2006

Author

Sandra Yin

Former Associate Editor

At 300 million, a milestone reached in October, Americans are consuming natural resources at an unprecedented pace. Between 1950 and 2005, America’s population nearly doubled. But in many cases, our consumption of resources more than doubled:

- Overall energy consumption nearly tripled (see Figure 1). Petroleum consumption within the transportation sector rose more than 300 percent between 1950 and 2005.1

- Wood consumption was up 171 percent between 1950 and 2002.2

- Coal consumption increased by 128 percent from 1950 to 2005.3

- Water use was up 127 percent between 1950 and 2000.4

Figure 1

Energy consumption per year rose from 35 quadrillion Btu to 100 quadrillion Btu between 1950 and 2005.

Source: Energy Information Administration, Annual Energy Review 2005.

The United States’ reaching 300 million people might not seem relevant at a global level. After all, the United States represents just 5 percent of the world population. But it consumes disproportionately larger amounts than any other nation in the world—at least one-quarter of practically every natural resource. And because it is the only industrialized country in the world still experiencing significant population growth, this high rate of resource consumption is expected to continue.5 “Each person in the U.S. contributes more to the global phenomenon [of natural resource consumption] than other people,” says Victoria Markham, director of the Center for Environment and Population, and author of the U.S. National Report on Population and Environment.

What’s behind Americans’ voracious appetite for resources?

Sometimes it’s a lifestyle choice.

In 2001, Michael Frisby moved his family of four from a 3,700 sq. ft. house in Mitchellville, Md., to an 11,000-square-foot house in Fulton, Md. Amenities in the five-bedroom/five-bath house which sits on a 3.5-acre lot include a music room, steam room, and media room.

“I always wanted a house big enough that my kids could be in their room screaming, and my wife could be in a room screaming, and I could be somewhere else and not hear any of them,” he says. “And I think I have accomplished this with this house, because this house is so big that everyone has their own space.”6

Frisby is on the leading edge of a national trend toward larger houses. In 1950, the average new single-family home was 983 square feet. By 2004, it was more than twice that: 2,349 square feet. Although new houses may be more energy efficient than the houses of the past, they require more resources to build and use.7