Aïssata Fall

Africa Director, Regional Representative for West and Central Africa

May 19, 2025

Africa Director, Regional Representative for West and Central Africa

As the world moves through a succession of crises—protracted conflicts, growing inequalities, economic instability, climate disruption— the question of social resilience has become more urgent than ever. Public systems are under strain, tensions are rising, and families everywhere are absorbing the first shocks. Amid this uncertainty, we must ask: what still holds our societies together? What are the invisible mechanisms that keep us going, despite everything? Among them, one essential pillar is too often overlooked: unpaid care work.

Social resilience is the collective ability to withstand crises without collapse, to recover equitably while preserving cohesion, dignity, and fundamental rights. It relies on solidarity, inclusion, adaptability—and above all, on effective and accessible social protection systems.

In Africa, social protection remains largely built on a contributory model tied to formal employment. And yet, fewer than 15% of the working population are in the formal sector, meaning the vast majority have no access to full coverage of social risks. Non-contributory programs are fragmented and insufficient to address this structural inequality. Moreover, nearly 30% of working people—whether formal or informal—live in poverty: they cannot protect themselves, nor can they carry the weight of national solidarity alone.

The current model is no longer enough. To assess resilience, we must ask: who supports whom, how, and with what resources?

Too often, families silently serve as the primary safety net. Every day, they provide the care needed to sustain social and economic life: feeding, nursing, educating, assisting. This invisible labor, fundamental to the functioning of society, is neither counted, nor recognized, nor protected.

In times of crisis, it is these caregivers—mostly women—who maintain the continuity of daily life. Their presence allows institutions to buy time, economies to function, and families to preserve their dignity. This labor serves as a vital social buffer, making care a core social function: it is not merely a private role, but a collective service as essential as schools or infrastructure.

Yet family structures are changing, intergenerational solidarity is weakening, and economic pressures are mounting. Families are stretched thin, women are burning out, and public systems can no longer absorb growing needs. It is time to recognize caregivers as strategic actors in collective resilience.

Advocacy around unpaid care work often focuses solely on a call for recognition. But recognizing care without understanding its nature, scale, and age- and gender-based dynamics risks misdirecting public policy—or even reinforcing inequalities.

Today, tools like the National Transfer Accounts (NTA) and National Time Transfer Accounts (NTTA) allow us to quantify, value, and integrate this invisible labor into economic analysis. They offer a strong evidence base to design policies that reflect age, gender, household structure, and demographic change.

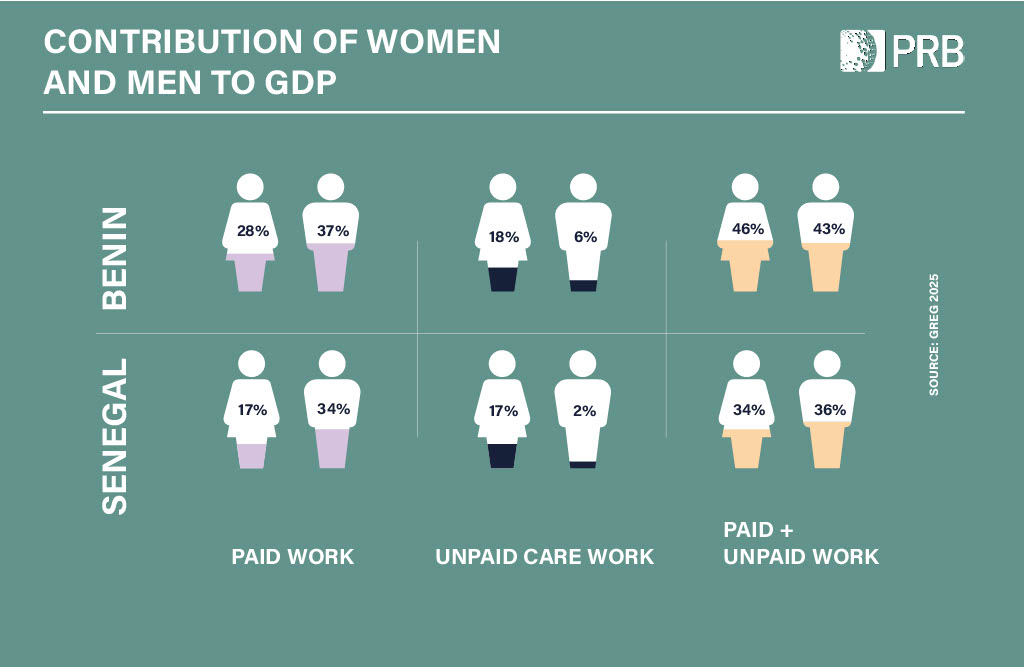

This data clearly show that when unpaid care work is included, actual economic contribution is far more evenly distributed across the population than labor market indicators suggest. When this invisible work is accounted for, women contribute as much—or more—than men to national economies. A significant share of the wealth produced is simply ignored by standard economic models. CREG estimates (2023) show that in Benin and Senegal, paid work accounts for 37% and 34% of GDP for men, compared to 28% and 17% for women, respectively. However, when unpaid domestic and care work is included, women’s total contribution reaches 46% of GDP in Benin and 34% in Senegal, compared to 43% and 36% for men. These findings confirm that unpaid care work represents a major reservoir of wealth and well-being, still largely underestimated in traditional analytical frameworks.

This work, most often carried out by families, represents a substantial economic effort that appears in no budget line—yet it upholds social cohesion and the continuity of systems. This invisible burden also reduces families’ capacity to focus on their own development and fulfill their human capital potential. Estimates produced in 2022 by CREG, using social accounting matrices, show that invisible solidarities amounted to approximately USD 30 billion in Kenya (25 times the value of visible solidarities), USD 5 billion in Senegal (86 times more), and USD 2 billion in Togo (13 times more), revealing the critical scale of these unaccounted contributions to national economies.

What this data changes is not only our perception of reality—it challenges the very definitions of “work,” “production,” and “growth.”

This is not simply a matter of fairness or moral principle: it is a matter of economic clarity, policy efficiency, and collective performance. Ignoring this contribution means building public policy on a distorted understanding of how societies actually function.

This analysis reveals a stark paradox: the people who uphold society through invisible care work are not protected by the very systems they sustain. They have no access to social benefits, paid leave, or affordable childcare and elder support. They have no recognized rights for fulfilling a role that is vital to social cohesion and human development.

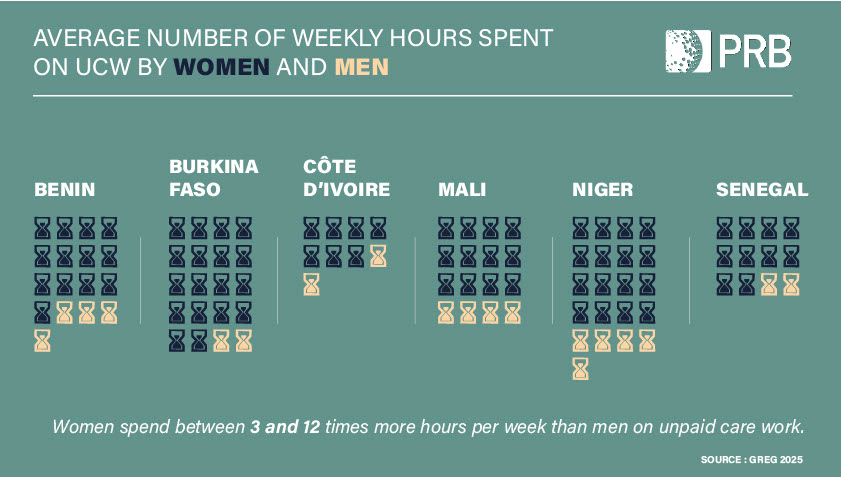

In practice, the majority of these unpaid care roles are carried out by women. The analyses reveal significant disparities in time allocation for unpaid care work: in West Africa, women spend between 3 and 12 times more time per week than men on unpaid domestic and care work.

This unequal distribution of time and responsibility deepens barriers to their access to decent work and restricts their economic opportunities.

This gap between public interest and institutional invisibility highlights the limits of current protection models. Without a fair redistribution of care responsibilities, there can be no intergenerational resilience, economic justice, or lasting social cohesion.

Unpaid care work is not simply a private or family matter. It is a societal issue, a development lever, and a pillar of collective resilience.

Care work is not a “bonus”: it is an invisible yet essential foundation of our societies. Recognizing it, measuring it, and supporting it is key to ensuring durable, equitable, and human-centered resilience. We must engage in a genuine dialogue on shared responsibilities, the value of care, and the role of social protection in building just, strong, and inclusive societies.

Because without care, there is no life. And without justice in care, there will be no social justice.

For nearly a decade, CREG and PRB have worked closely to make care work visible and a part of policy dialogues, producing data, economic analysis, and communication tools that demonstrate unpaid care work as a fundamental element of social infrastructure, without which no society can function sustainably.

Through the Counting Women’s Work Africa project, funded by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, we support governments, civil society, and parliaments in better integrating unpaid care work into public policy. Drawing on NTA and NTTA data, we demonstrate why better care policies matter—not only for gender equality and the economy but also for social resilience. We are working to ensure this recognition is accompanied by an informed policy dialogue grounded in lived realities and sound evidence.