Collaborating for Action on the Future of Demographic and Health Surveys

This convening held on May 7-8, 2025, brought together key stakeholders—including leaders from National Statistical Offices, donor organizations, partner organizations, and data user groups—to identify opportunities and priorities for collaboration to protect current data and preserve ongoing data collection activities.

Date

June 25, 2025

Meeting Report

Since 1984, USAID has funded the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program to provide technical assistance to more than 400 surveys in over 90 countries. On February 24, 2025, the U.S. government terminated the DHS Program. In the aftermath of the termination, numerous efforts have emerged to mobilize action to sustain collection of high-quality demographic and health data through surveys. These efforts span a range of critical challenges, including preservation and accessibility of current data, completion of near-final surveys, and identifying long-term strategies to support future data collection. As multiple streams of effort have emerged, PRB organized a virtual global convening to support coordination and collaboration.

The convening brought together key stakeholders—including leaders from National Statistical Offices, donor organizations, partner organizations, and data user groups—to identify opportunities and priorities for collaboration to protect current data and preserve ongoing data collection activities. This event created a space to identify needs, gaps, opportunities, and emerging solutions; share efforts that are underway; and support ongoing coordination among stakeholders moving forward.

This meeting report summarizes the discussion and ideas shared in the convening. Each topic, objective, and related stakeholder discussion is presented, with little interpretation, to form a record of the conversation and ideas that arose. This report concludes with a summary of emerging next steps.

For questions about the report or to learn more about ways to engage ongoing dialogue on the future of the DHS, contact Kaitlyn Patierno (kpatierno@prb.org).

Fact Sheet: Trends in Family Care for Older Americans

In the United States, over 24 million people provide unpaid care for older adults—a 32% increase from a decade ago

Date

March 18, 2025

AUTHORS

Mark Mather

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

Paola Scommegna

Contributing Senior Writer

Focus Area

As the large Baby Boom generation enters advanced ages, more family members and other unpaid helpers are stepping in as caregivers. In just over a decade, the number of family caregivers regularly assisting older adults with daily activities at home grew by 32%, increasing from 18.2 million to 24.1 million between 2011 and 2022.1

While the caregiving cadre has grown, who’s getting care has also changed. Older Americans receiving family care are younger, better educated, and less likely to have dementia than they were in 2011, report Jennifer L. Wolff of Johns Hopkins University, independent consultant Jennifer C. Cornman, and Vicki A. Freedman of the University of Michigan.

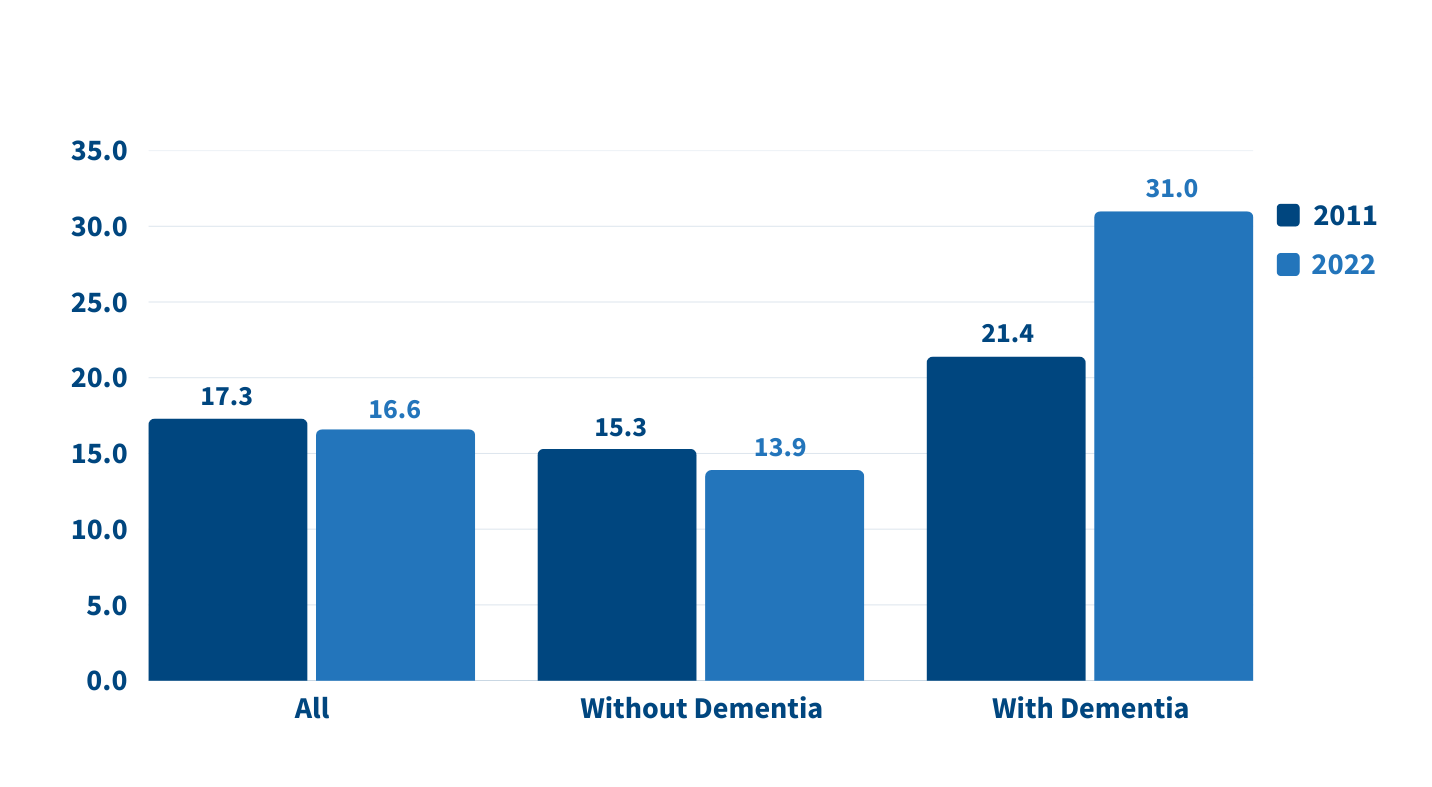

The increase in family caregiving partly reflects the rising share of older adults with multiple chronic conditions, such as heart disease, hypertension, stroke, and cancer. And while the share of older adults with dementia has declined, unpaid caregivers average twice as many hours each week caring for people with dementia than without dementia (about 31 hours versus 14), Wolff and team found (see Figure 1).

In addition, a new study estimates that the number of new dementia cases will double over the next 40 years as the population ages—setting the stage for more demands on dementia caregivers and more changes to the caregiving landscape.

“Understanding the changing composition and experiences of family caregiving has never been more important, but it is challenging to assess,” the researchers write. “[It] requires consistent measurement for well-characterized, generalizable samples of people who receive and provide help.”

The nationally representative National Study of Caregiving and the National Health and Aging Trends Study offer important insights. The two studies provide a snapshot of the family caregivers that help Americans ages 65+ who live in the community (i.e., at home or with a relative) or in a residential care setting other than a skilled nursing facility, such as an assisted or independent living facility, a personal care home, or a continuing care retirement community.

Family caregivers include relatives and unpaid helpers, like neighbors and friends, who assist with personal care tasks like bathing and dressing; mobility tasks like getting out of bed and getting around the house; and household activities such as laundry, food preparation, shopping, and managing money.

Dementia Caregivers See Increasing Demands on Their Time, Employment Woes

On average, the time that family caregivers spent helping older adults with dementia increased by almost 50% over the decade, rising from 21.4 hours per week in 2011 to 31.0 hours in 2022. By contrast, time spent assisting older adults without dementia fell from 15.3 hours a week in 2011 to 13.9 hours in 2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Family Caregivers Are Spending 50% More Time Caring for Older Adults With Dementia

Average Weekly Family Caregiving Hours, by the Dementia Status of Older Adults (65+), 2011 and 2022

Source: Jennifer L. Wolff, Jennifer C. Cornman, and Vicki A. Freedman, “The Number of Family Caregivers Helping Older US Adults Increased From 18 Million to 24 Million, 2011–22,” Health Affairs 44, no. 2 (2025): 189-95.

People caring for older adults with dementia have high—and increasing—demands on their time. More than half (51.7%) of dementia caregivers lived with the person they were caring for in 2022, up from 39.4% in 2011, Wolff and team report. And the share able to hold jobs—outside their caregiving work—dropped from 42.5% to 34.6% during the same period.

Among caregivers with formal jobs, the share who reported challenges with their employment—including working fewer hours or being less productive—increased over the decade, regardless of whether they cared for someone for dementia.

“Challenges are exacerbated when caregivers are in poor health themselves; have a lack of choice in assuming the caregiving role; and, for the substantial proportion of family caregivers who are employed, work in low-wage jobs with limited flexibility,” the researchers note.

Care Recipients Are Mainly Older Women, but the Share of Men Receiving Care Is Growing

Which older Americans get family care? As in the past, they tend to be female, non-Hispanic white women who are married or widowed. But growing numbers of family care recipients are male and have some college education. More are also separated and divorced compared to 2011, reflecting national trends.

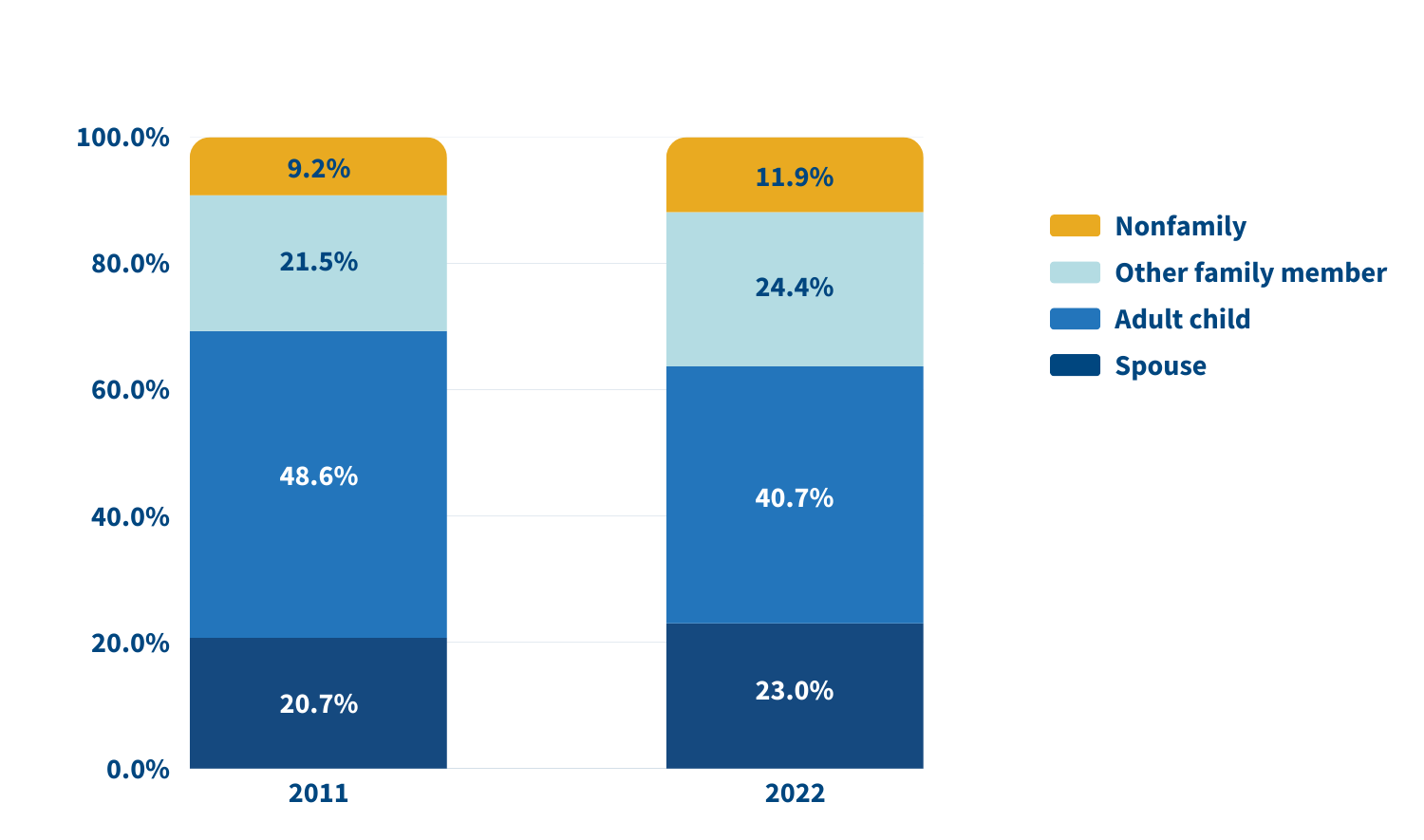

Adult Children Continue to Care for Their Parents

Who’s providing care? Family caregivers continue to be largely female and married, and most report being in good health. In 2022, adult children still made up the largest share of family caregivers for older adults, at 40.7%, but this represents a significant decline since 2011 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The Share of Adult Children Caring for Older Relatives Has Declined

Relationship of Family Caregivers to Adults Ages 65 and Older Receiving Care, 2011 and 2022

Source: Jennifer L. Wolff, Jennifer C. Cornman, and Vicki A. Freedman, “The Number of Family Caregivers Helping Older US Adults Increased From 18 Million to 24 Million, 2011–22,” Health Affairs 44, no. 2 (2025): 189-95.

In 2022, adult children accounted for about half (49.1%) of family caregivers for older adults with dementia, compared with 38.4% of caregivers for those without dementia. Just 17.7% of family caregivers for older adults with dementia were spouses, compared with 24.5% of family caregivers for people without dementia.

A sizeable share of family caregivers (17.0%) had children under age 18 at home in 2022, and 6% to 13% viewed their care responsibilities for older adults as a source of financial, physical, or emotional difficulty.

Despite these challenges, the researchers report a decline in the use of support groups (4.1% to 2.5%) and respite services (12.9% to 9.3%) between 2011 and 2022.

Trends and Policy Implications

Many caregivers face extraordinary demands and should be the focus of support services, Wolff and colleagues say. They single out those caring for older adults with dementia or nearing the end of life, as well as caregivers “from racial and ethnic minority groups who are more likely to assist people who have extensive care needs in circumstances that involve scare economic resources.”

Family care needs are likely to rise as the number of U.S. adults ages 85 and older is projected to triple by 2050. The researchers note that the number of family caregivers rose even as the long-term use of skilled nursing facilities among older Americans dropped and community living increased. The challenges these caregivers continue to face is “sobering,” they write, including competing time demands from work and child care while spending an average of 17 hours per week on care. In addition, about 1 in 8 family caregivers report financial, physical, or emotional difficulties related to their caregiving roles, percentages that were largely unchanged over the 11 years examined.

Policies and programs to help reduce the financial, physical, and emotional burden of caregiving exist, but do not represent a coherent strategy, the researchers say. “Local, state, and federal policies are a patchwork that is uneven in availability and largely symbolic in magnitude,” they argue. Addressing the needs of family caregivers will require a “cohesive framework in support of the care economy.”

References

1. Jennifer L. Wolff, Jennifer C. Cornman, and Vicki A. Freedman, “The Number of Family Caregivers Helping Older US Adults Increased From 18 Million to 24 Million, 2011–22,” Health Affairs 44, no. 2 (2025): 189-95.

Date

March 18, 2025

English Publication

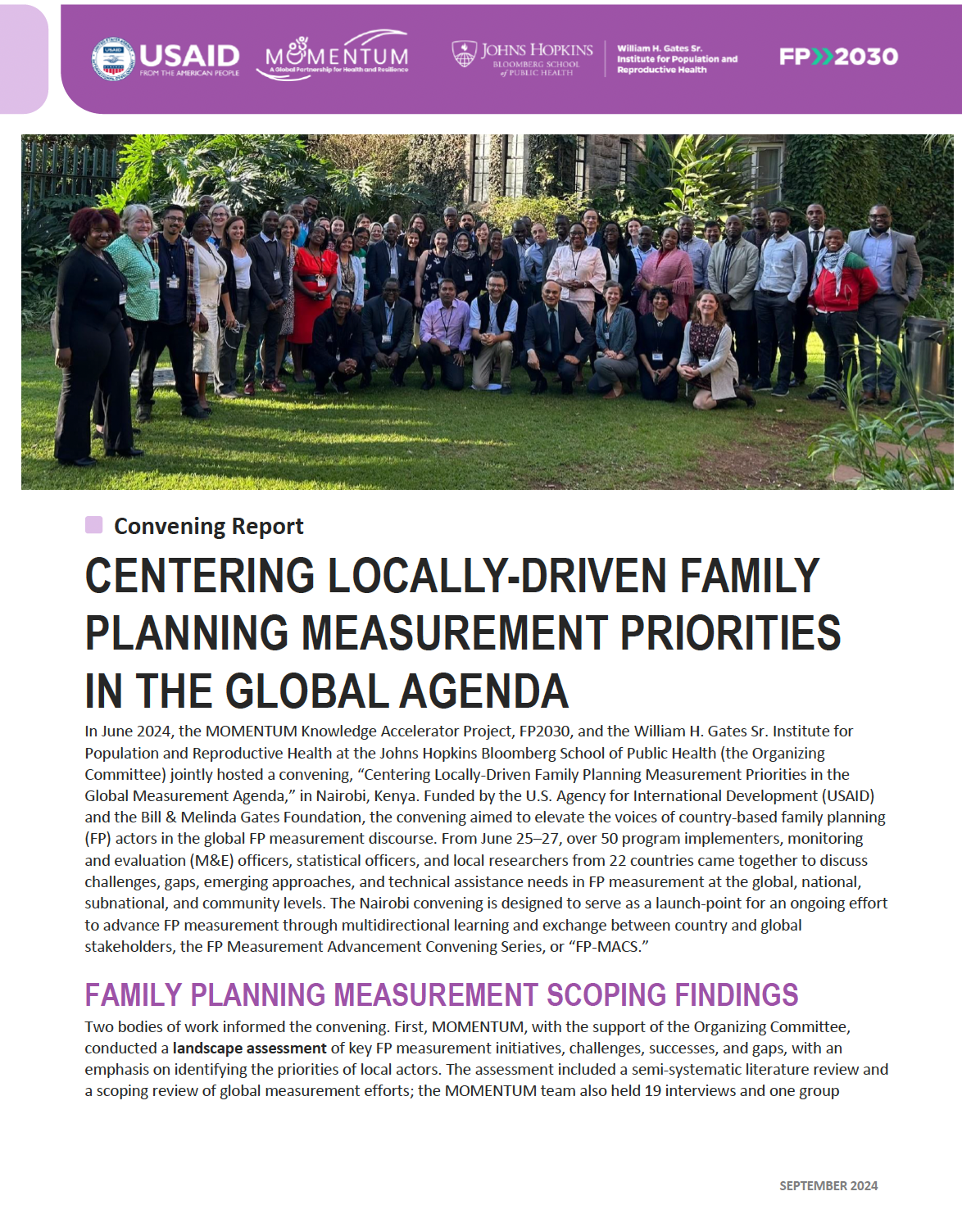

In June 2024, the MOMENTUM Knowledge Accelerator Project, FP2030, and the William H. Gates Sr. Institute for Population and Reproductive Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (the Organizing Committee) jointly hosted a convening, “Centering Locally-Driven Family Planning Measurement Priorities in the Global Measurement Agenda,” in Nairobi, Kenya. Funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the convening aimed to elevate the voices of country-based family planning (FP) actors in the global FP measurement discourse. From June 25–27, over 50 program implementers, monitoring and evaluation (M&E) officers, statistical officers, and local researchers from 22 countries came together to discuss challenges, gaps, emerging approaches, and technical assistance needs in FP measurement at the global, national, subnational, and community levels. The Nairobi convening is designed to serve as a launch-point for an ongoing effort to advance FP measurement through multidirectional learning and exchange between country and global stakeholders, the FP Measurement Advancement Convening Series, or “FP-MACS.”

Webinar: The Pros and Cons of Virtual vs. In-Person Interaction for Older Adults

Date

March 18, 2025

In this March 4, 2025 webinar, three researchers discussed how social media and new technologies may enhance—or limit—social connectedness and emotional well-being among older adults.

- Karen L. Fingerman (University of Texas at Austin) focused on the relationships between social media use, social ties, and emotional well-being in later life.

- Ellen L. Compernolle (NORC at the University of Chicago) summarized research on loneliness among older adults from Chicago during and before the COVID-19 Pandemic.

- Steven W. Cole (University of California at Los Angeles) described how in-person and virtual social environments influenced gene expression during the COVID-19 Pandemic.

This webinar was hosted by PRB and the Coordinating Center for the Centers on the Demography and Economics of Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias, with funding from the National Institute on Aging.

Webinar: Bridging Research and Policies: Enhancing Budgeting Processes for Africa's Demographic Dividend

PRB hosted a high-level webinar with budget experts, parliamentarians, and national directors to discuss the importance of the Demographic Dividend Sensitive Budgeting approach in enhancing budgeting processes across Africa.

Date

January 24, 2025

Texte français à venir.

On Aug. 6, 2024, PRB’s Africa Director, Aïssata Fall, hosted a high-level webinar with budget experts, parliamentarians, and national directors to discuss the importance of the Demographic Dividend Sensitive Budgeting (DDSB) approach in enhancing budgeting processes across Africa. The webinar, “Bridging Research and Policies: Enhancing Budgeting Processes Africa’s Demographic Dividend,” was held in coordination with the Regional Consortium for Research in Generational Economy (CREG), a nonprofit based in Senegal led by Prof. Latif Dramani. It is available in English and French.

Panelists include:

- Prof. Latif Dramani, President and Coordinator, Consortium Régional pour la Recherche en Economie Générationnelle (CREG), Senegal

- Pr. Germaine Anate, Professor, Director of the Center for Studies and Research on Organizations, Communication, and Education; University of Lomé, Togo

- Ms. Astou Diouf, National Director of Gender Equity and Equality, Ministry of Family and Solidarity, Senegal

- Miss Mariama Fanneh, Director, National Population Council, The Gambia

- Dr. Larba Issa Kobyagda, Director General of Economy and Planning, Ministry of Economy, Finance, and Development, Burkina Faso; Coordinator, National Observatory of the Demographic Dividend, Burkina Faso

- Mr. Moussa Sidibe, National Coordinator, Sahel Women’s Empowerment and Demographic Dividend (SWEDD) project, Mali

Transcript

Aïssata Fall, Africa Director, PRB: To better achieve our development goals and more specifically, we will be talking about budgeting processes in order to enhance Africa’s demographic dividends. Demographic dividends is an issue that is being widely spoken about, and sometimes it seems theoretical or abstract. But today we are fortunate to be able to look at this more concretely and look at some of the processes that have been developed and put into place with the help of the African Union and several African countries to help capture some of these demographic dividends by investing in youth and in women. And our presenters today will be talking about how research in Africa has been helping to better analyze and create tools in collaboration with technical staff from various governments, specifically in French speaking Africa, in order to create these tools and provide them to decisionmakers to help them better plan and be able to really capture the demographic dividends.

We will have Professor Dramani, who is the coordinator of the CREG, in Senegal. He will be speaking to you, and first he will be talking about a tool that is the budgeting tool that is sensitive to demographic dividends. And he’ll be talking about how we can use public expenditures to better enhance these dividends.

Let me give you just a moment. I am having a connection, let me ask you to give me just a minute, 30 seconds, I’m having a connection issue here in Dakar, and I need to switch networks.

I think that is better.

Professor Dramani has his doctorate in Economy from Senegal, and he is a Professor at the University of Thiès and Coordinator of the Center for Research and Applied Economics and Finance -Thies, representing Africa in the National Transfer Accounts Network. He is also the coordinator of the Regional Center of Excellence in Generational Economics, or CREG, and Africa’s representative in the NTA Network. Professor Dramani is affiliated with several universities around the world: University of Manchester, Berkley, Baku State University, University of Cape Town, University of Hawaii, and he’s the author of several scientific and programmatic works. Professor Dramani primarily conducts research on sustainable development through the lens of demographic dividend and generational economics, poverty dynamics, unpaid domestic work, and women’s contributions to GDP. And finally, he works on national and local economic integration. So, I would now like to give the floor to Professor Dramani, who will be speaking to us in French. Professor Dramani, if you could turn on your camera. Over to you, Professor Dramani.

Prof. Latif Dramani, President and Coordinator, CREG: Thank you very much. And good morning. Good afternoon, everyone. Thank you, Aïssata. And thank you to PRB.

I would like to say hello to everybody, all the colleagues online, all the participants who have joined us on our call today. I see a lot of friends online, and a lot of colleagues from many different institutions. It’s a pleasure to see you and as Aïssata was saying, I’m going to give a brief presentation, opening up our webinar to get our discussion started. We have two presentations today. We have a presentation that will be focusing on policymakers and then also presentations, focusing on researchers who will be talking about some of the tools they’re developing. And we will also be sharing links with all the, for all these tools from NTA that will be of use for the researchers, and especially if they want to get more into the technical and scientific issues. Thank you once again and to Aissata and all the colleagues from PRB for all the work you have done to organize today’s webinar.

Next slide please.

We have been attempting to see how we can integrate demographic dynamics into development policies and the ICPD Cairo resolution has been from 1994, has been seeking to integrate demographic dynamics into these policies as a priority. We also have the African Union’s Agenda 2063, which was launched in 2013. For the Africa we want, which is a strategic framework for the social economic transformation of the African continent over a 50-year period, looking at how we can capitalize on the potential of youth and women. We also have the African Union 2017 Roadmap on Harnessing the Demographic Dividend through investments in the youth. And this roadmap contains four pillars Employment and entrepreneurship, education and skills development, health and wellbeing, which is pillar three and then pillar for law, governance and youth empowerment.

So, this is the framework in which we have been conducting this work looking at demographic dynamics and we are going to be looking at all of these frameworks. The Cairo resolution from 1994, the African Unions agenda 2063. These are all important frameworks to help us, spur this work and give us a basis for all this work that we will be presenting today.

Next slide please.

So, our NTA network has published this was in 2022, published some of the, document about the major, one slide back, please, about some of the major international trends. One slide back. Thank you. So these are some of the major global trends about demographic change and how it impacts the global economy and overall we see that there were six main outcomes in terms of these trends. That, first of all, Africa is the continent that has the youngest population right now, Africa is more and more going to continue having growth. And we’re seeing a huge demographic explosion in Africa. But this is not necessarily the case at the global level or in other countries where the other countries are facing issues of an aging population. So, we are looking at how we can really enhance and maximize these demographic dividends, and where we can best invest our resources in which sectors, which are the priority sectors in an environment where there are limited resources, where can we best invest our resources? So, this overall is the overview that we see from this document about the impacts on the global economy and demographic trends, and looking more specifically at Africa with its young population and how we can benefit from this demographic growth, whereas in other continents we are seeing an aging population.

Next slide please.

In this perspective, there is a whole range of tools that have been developed, and the tools that were developed are aligned with the AU’s roadmap on capturing demographic dividends. So, among these tools, there were tools to analyze and understand the impacts on the economy, the impacts of demographic growth on economic. So, population economics as we said. And because all leaders when they come to power whether it’s in the DRC or Senegal or various countries. In Kenya, we’re seeing that our leaders are facing this issue of social demands with the new generation because they are more and more demanding and this is a huge problem for many leaders. So, we are developing tools to analyze these pressures. Also, tools to help measure and to monitor demographic dividends. We’ve also been developing tools that will enable us to see how demographic dividends can be better aligned or integrated into national development plans in our countries because, as all economists know, as well as development actors, if we don’t have budgeting policies that are sound and integrated we are not going to be able to capture these dividends. So, we have developed a whole range of tools with support from the NTA network that we are a member of. We have also worked with UNFPA, which contributed greatly, especially in the West African countries. We have, The Hewlett Foundation, that also provided a lot of support in developing these tools. So, we have a number of partners, we have the NTA profile and NTTA profile, that looks at how all individuals produce, consume and share and savings. So, we have about 30 African countries right now who have developed profiles. And then we have the National Time Transfer Account (NTTA), which quantifies and values an unpaid domestic works contribution to the economy. Whereas the National Transfer Accounts (NTA), they examine how individuals produce, consume, share and save resources. But the NTTA focuses more on unpaid domestic work. Also, we have tools that measure the contributions of persons with disabilities, which is often not accounted for.

We also have tools to monitor dividends, which we call the DD monitoring rather monitoring index. This tracks progress implementation and in the African Union’s roadmap through five dimensions. And then we have the GDDI, the gender index, which measures the differentiation of women and men’s participation in achieving demographic dividends. And then we have the BSDD, the budgeting sensitive to demographic dividend, which assesses demographic dividend issues and budget allocation and effective consideration of DD and public policies. So, these are the tools that were developed, and they are aligned with the recommendations in the AU roadmap.

Next slide please.

Here we show an example of some of the results. And this is a result from the NTA. And this is the example from Togo, if you look at the graph on the left in red you have consumption by age, aggregated consumption by age from childhood through working age and then older persons. And what we observe here is that, and this is a country that is an example of what we see in many African countries where we have a youth bulge, and the fact that consumption. Is quite high in earlier years. And this shows that there is a huge problem in terms of being able to meet consumer needs for young people. And then we see that there’s also a surplus during the working age, you see that in light blue where we don’t overcome these two deficits, the two deficits that we see in among youth and working aged person. So, this is part of the analysis from the NTA that looks at the whole population economy to see what trends are occurring in a country. And then we also have the support ratio, where we look at the number of effective producers and the number of effective consumers. So, if everybody works, then you didn’t have the same productivity necessarily. Uh, somebody may be working more hours a day than another person, or somebody may, for example, for a surgeon or a doctor, they might be spending some days just doing medical visits and other days during surgery, saving lives that it’s not necessarily the same degree of productivity. So that’s how we look at effective producers and then effective consumers. This takes into account the consumer needs and the fact that they vary with age. A child is not going to consume the same amount as a young person or an adolescent who’s not going to consume the same amount as an adult or an elderly person. So that’s what we mean by effective consumers. And this is what we’re looking at with the NTA tool and we’re looking at the growth rate and what we call the primary dividends. And overall, this is an overview, a quick overview of the basis for all this work that we have been conducting to look. Of course, economies have a certain life cycle. And we look at the households at the microeconomic level. But then we look at the state at the macro-economic level.

Next slide please.

Here we have looked at this as data that is disaggregated by sex or by gender.

And what you see here is that there is a predominance of men on the market, and that is in the blue line, where you see the men’s average labor income, and then you see the women’s average labor income in red, and you can see that men predominate or dominate in Togo throughout the whole life cycle. There’s a dominance of men over women in terms of the labor market. And so, where the market is, where money is circulating, it is men who are dominating.

And this is illustrated here with the case of Togo.

Next slide please.

So, this looked at the market, but there is another market and that is the domestic market where it is much more about the older types of work you know, so non unpaid domestic work. So, every one of us at home do a certain type of work, even, uh, women, even if they were to have servants, they do certain work at home. And this is not counted within national accounts, but this work is at the very heart of the dividend, because without this work, being done, nobody can get out of the house to go work elsewhere. So, this is very important, uh, you know, this socialization that exists there, there are all these implicit contracts in terms of social cohesion. So, this is a very important work that contributes to the population, but it is not accounted for. In terms of the University of Berkeley, we are attempting to achieve an international harmonization of a way to account for this time used within households. So, we will call it NTTA, the national time transfer accounts. This has to do with all everything we do about women empowerment, gender equality etc.

The following slide.

Okay, here we see an illustrative example. So, we have this profile that you see on the screen that shows you the number of hours per week that are produced and consumed. So, the dark red line, that is the position of time in women. So, you see that woman, produce a maximum of 20 hours per week, let’s recall that 40 hours as a work week. If you look at men, their maximum is six hours, seven hours per week.

So, if you look at 15 years old or 20 years old, you will see that young women and their male equivalents, they produce much more domestic work in terms of time. And this really, you know, so in the SWEDD project, we’re currently really looking into dropping out how why women drop out of school. so young women are dropping out of school not because they want to, but because there is this amount of time that is part of socialization. That is because they are women. So, they have, say, 15 hours of work. So you have a woman who is at university, she has to spend 20 hours working in the home. This is enormous. So and this work is unpaid. So it is not accounted for within national accounts. It is almost invisible work labor. And then, you know, when we talk to parliamentarians, you know, like in Senegal, we were told, oh No, we must say that this work is not used in accounting. So first we have to acknowledge that women do a lot of work. And this is what we’re going to detail here. Everybody works for a number of hours, but not everyone produces during these hours. So, you know, when you have young children or elders that you have to take care of, that is one thing.

Next slide please

So, we looked at a few countries that are represented here. So, we looked at Niger, Cote d’Ivoire, and a few other countries in terms of paid work and unpaid work. So, what you can see here If you look at, you know, the production of type like for example, in Cote d’Ivoire and Niger so we showed that in could Cote d’Ivoire we had the weakest estimates in terms of time, in terms of domestic working time. These were the lowest amounts, this is tied to socialization in Cote d’Ivoire. In Niger we found the highest times. And this again has to do with the socialization in Niger, because the fact that from a sociological standpoint women get married very early, very young. And so in terms of time you know, they have around six children on average. So you can imagine it takes time to take care of that many children. And they get married very young, around 16, 17 years old and so between that and up to 45 years old, they’re spending all this time. So, this takes time and, and all the other domestic work that they have to do. So that is what we’re trying to illustrate here. Here we have a deficit of care because in the. Here we see a lack of sufficient care throughout the life cycle. So, this is care for young children and elder individuals. And this is shown on the slide.

So, there we did a quick we took stock of the NTA and NTTA, this is very the basis of the work that we are doing. And the African Union has asked for the creation of an index for the monitoring of the demographic dividend. So this is how the DDMI was established, which is made up of four pillars, uh, with five dimensions. So pillar one was employment and entrepreneurship so this pillar one is covered by three dimensions of the DDMI, economic dependency. That is the first one dimension to is quality of living conditions and dimension three is poverty transition. And then the second pillar about education and the development of skills, and then the pillar on health and well-being, which is, um, fueled by dimension four, which we’ve talked about, which we’ve called extended human development, which makes us able to see the human and development at the national and subnational level. And then we have of course, rights, governance and youth empowerment. This is fueled by dimension five and also dimension two. And this is everything that has to do about, the arrangement of the territory the having potential opportunities at the national level, not just in some regions, as we see in most of our countries at this time. And the fact that people must have access to services, young people, women must have access to reproductive services, health services, infrastructures, transportation services, financial services, for example, throughout the entirety of the country’s territories. So that’s dimension five of DDMI. And we have results for about a dozen countries in West and Central Africa.

Next slide.

So we have GDDI and its gender specific version because we know that women represent 51 to 50%, 52% of the population in general. So, we saw earlier with Togo and what we saw for Togo is pretty much what we see throughout Africa. We have inequality between the genders. So, the DDMI index was divided by gender. So the GDDI gender, demographic dividend and to see how we could budgetize to take care of national issues, but also taking care of this 52% of the population. That is enormous, because as we saw it, is the women who contribute the most to socialization and do all this unpaid work that is not accounted for at the national level. So, this can represent 10 to 25% of GDP in countries. That is the estimate we have for the region.

Next slide.

So, this brings us once we developed all these indexes. So we have the basic preferences that show us where things are not going well. So we can go okay. It is not going well here. But the plan, the diagram is not complete. When you look at this diagram, you can see it’s incomplete as someone who is a policymaker, etc. And then you have issues of equity, territorial planning, etc. you have equity issues. But the question is what do you do with all this? So this is where Democratic Dividend sensitive budgeting originates, because it’s not just a we can’t just stop here. You know, this gives us a diagnostic it tells us what to do. But how do we do it? We need public resources. Demographic dividend sensitive budgeting is because we are talking about public funds everything that we know about economic theory is that the state is the sole guarantor of collective good. A private person cannot create and build an airport. It will be his airport. It will not be a public airport. So when we’re talking about public funds, they are what is going to be used to take care of all these problems? How to use these resources to obtain the benefits of this demographic dividend. So, the DDMI that we talked about with five dimensions, it is very much a diagnostic tool, but it’s not really legible for those who take care of budgeting, those who are in charge of public finance, they really want things to be very clear for them. This is why the BSDD was created. So, this is about budgeting, we broke down the index so that it could become understandable to our friends who create budgets within our countries. So we created four components that can be used by any country. The first one, the first component is human capital, then second governance, then economic structure and the fourth component is network. And within each of these there are two functions, first education and health, which fall under human capital. Under governance you have institutions and security, under economic structure you have economic affairs and infrastructures, public works, energy and then networks you have specialized networks, which we call social networks and professional networks. So this is the normal type of nomenclature that can be understood by people who take care of budgeting. And this is actually informed by the DMI. So here we have this results indicator, the DMI, which is now anchored to the budget via this table. These four components. so this is the very core of what we want to talk about today. We this was what was asked for by our leaders. You know, we know we have finance. We have a growth in the youth population, but we must establish priorities. You know, in a developing country, everything is important. So what is the priority? So this work has been done to establish where the priorities lie in terms of budgeting, where do, where must authorities make strategic investments, you know, and where do these authorities, decide that they must do very specific things, things like commercial plans, essentially, have a total rupture from the past.

So here these are the first results of BSDD demographic dividend sensitive budgeting. This is the structure of budgets. So when we analyze the budgets of our countries, when we talk about, you know, it’s often analyzed in terms of percentage of increase of growth. Yes. Growth is important, but what is even more important is the weight of each sector within the budget. So, when we talk about demographic dividend there are very simple things we can observe. So the dividend first must have a well-educated population that has skills and that is in good health. So there you will see the columns that are labeled education and health. What do you see there? So that’s the head. That is the top part. It is well formed. So now I must have an economy that can support this so that the infrastructure, you know the buildings and public works, etc. so we can have an economy without energy to, for example you know, create electricity and manufacturing etc. So that is very important. So on top we have education, so that’s the head of the body. Then we have the spinal cord is the structure of the economy. And then we have governance coordination, So we have security, So we have laws. And then finally we need social cohesion. We need specialists, And that is your networks. So, you have the head, the spinal cord, two feet and two hands. So when you look at the structure, we observed that in our countries we allocated many more resources to institutions. Institutions consumed a lot of the budget. You know, look in, in comparison to the resources that so for example, the resources allocated to institutions and the resources allocated to health there you can see there is a problem. If you look at both those columns. Now, when you talk about gender, that’s about social matters. And look at the portion of the budget that is allocated in the various countries, to creating gender programing, you know, about gender equity to empower women, in order to improve the system. So then you have the social networks.

So apart from Mauritania, things are not going very well in that aspect. So this enables us to tell the authorities because you know, we’re talking about public expenditure. This is everybody’s money. So we need to tell the authorities things are not going right without, we can’t really benefit from the dividend in this way. We really need to change how we allocate resources. So that is an initial analysis of the first results of the first results that we have found in terms of the various countries noted on this slide.

So I talked about the various countries on the previous slide, but this is an average of all our countries together. So, you know, we have about 12 countries that we averaged out to get to these results. If you look at the budget structure you have 100% there. And then you can see how these budgets are allocated. So, you will see more specifically. So the budget does what you know is it used to invest. Is it used for operation or for transfers? I’ll take the line on Health First because without health you can’t get anywhere. So, let us talk about health, you have 6% in total on average between all these countries, when you look at the investment column, you see 1%. So as an economist, if I am not even as an economist, we can see that we do not have a good medical basis. We do not have the materials to achieve health within the population. So even if we have staff, we have personnel they cannot do anything because you need to have equipment to achieve health. So, we don’t have adequate medical equipment for our reality now. So the average is 6% but then look at institutions now just going down one line, that’s 32%. That is five times more, So institutions were originally created to coordinate the system, yet we see that they are taking up a lot of time, a lot of money. They are at 30% for investments, so 13 times higher than health. So, investments for institutions, it’s usually often equipment, cars, that sort of thing that is purchased. but it is more important for human capital to do a strategic investment rather than investment in these institutions. So we have countries undergoing crises. Well, so look at what is there. So we’re, you know, and then there’s the other sectors, sectors that are just sort of left aside. So we have a lack of balance among our budgets, basically we cannot benefit from the dividend with all this you have, it’s the institutions that are taking up most of the budget. There is no money allocated to health, to human capital, to education and you see that governance is actually more weighted than the economic structure. And so I am therefore a man whose spinal column could not support its arms if we do this body analogy. So basically, that means that we cannot stand as such because the spinal column cannot support the hands. So the spinal column is the economy. So, you have 14%, 10%. So these countries cannot stand up on their own feet until they can, really fix this issue and balance out the structure.

These are the initial steps of BSDD. They are the easiest to use, especially for policymakers and for everyone. Because okay, so you have public funds. This is our money. This is everybody is concerned by this. So we establish we provide the reasons why things are not going well. And these can be verified, because this is work that is done with various countries. It is done in an anonymous manner. So now is important to talk about issues of collaboration to bring about change because it is not obvious, but everybody has got to play their role. We have various stakeholders. So you have the sectorial ministries, you have the parliamentarians, you have civil society, you have researchers and the entire society. Everybody has to play their role because we learn while talking with parliamentarians that when they say that they can’t take on a problem if civil society doesn’t tell them, hey, there’s a problem here. And from a technical standpoint, we must strengthen the different sectorial ministries so that we can really start creating these services for our Populations strengthening skills, have communication an advocacy so that things can change. Especially, I really emphasize health because I really think without health, you cannot even begin to change things. Um, you know, the previous column we saw, we were about around a dozen countries where at about 6%. So there’s a lot of work to still be done. So we need for the tool to be truly used by the budget team so that they know that when they allocate resources, you know they are allocating resources for the development of their countries, but you can’t do it haphazardly. You need to find out what sectors you must invest in order to have results. And so this this tool can really allow us to seize upon this dividend. We have the youth, we have the young people, and they’re going to be around for quite a while, you know, but in 20 years, they’ll be 20 years older.

Next slide.

I really want to thank the SWEDD project and I want to, thank you the UNFPA, the Hewlett Foundation on the Counting Women’s Work, but they also supported us in our research and, and the fact that we were able to do this research with thanks to the Hewlett Foundation. We had Gates Institute also supported us in achieving these results. So thank you to all the stakeholders. Because what I just presented, this is 10-12 years of research work. And, you know, it may seem simple, but it’s it really represents 12 years of work for all from all these partners. So UNFPA, WCARO, Hewlett, UNECA, Gates Institute, etc. and of course, all the other partners we may have forgotten. The NTA network also has been a supporter since the very beginning, well before this program in order to really work on fundamental research on and as a applied researcher. Thank you so much, sorry, I took a little too much time. Thanks again Aïssata.

Aïssata Fall: Thank you very much, Professor Dramani. It was necessary for you to take that time. Professor Dramani, I cannot explain all the technical details. It is not really useful for me to repeat them but I think that this information is really important for us to continue having engagement. Engagement of all the member states of the EU, for the roadmap, for capturing demographic dividends, because this is going to be absolutely essential to really be able to capitalize on the youth contribution to this kind of these countries economies. We can also see the overall trend on the global level that these demographic trends are having an impact on economies. And we can’t ignore this. It is absolutely necessary and this started already back in 2014 when we were looking at this issue as part of a development issue.

Analysis show us and thanks to the work that we’ve done with the NTA and the NTTA, the analysis show us what is driving countries’ economies in terms of investments, but also not only money, but investments in terms of time. And this shows us we can’t ignore the fact that time is also a fundamental investment in order to have it. And we have to really have a good vision of the labor force in our countries, but also the policies that are going to allow every person, man or woman to be able to contribute to productively and fully to the growth of their countries’ economies. Another essential element, I think, is that in Africa, we have to look at the budget resources of states and in most cases, the government, the state is the main employer, and the private sector does not always dominate the market. It is more the public sector and so we need to see how we can also maximize the effectiveness of these tools and budgeting tools and processes. So now we’re going to be talking with some of our panelists who are representatives of their governments, who are talking, who are going to be talking to us about their budgeting processes and how they’re using these to capitalize on demographic dividends and before moving to our panelists, I would like to look at a few of the questions that we had for Professor Dramani, we have one question saying, when you look at the gender differences in terms of time spent on work, we can see that the differences start at a very young age. Is this a gender socialization issue, or is it an issue of early marriage? Or what are the issues that make this separation appear so?

Put a question in the Q&A. Could you retype in your questions please? And I will ask Professor Dramani to ask the first question that I had just asked right before we got cut off. Did you hear the question, professor Dramani? No. Could you repeat it again, please? Yes. The question. I’m not entirely sure I remember exactly what it was, but the fact that we see the set of this differentiation at a very young age in terms of time and is this different use of time, is this big difference at a young age? Is this because of working time? Is this because of socialization? Is it because of early marriages, or are there other factors that explain this different gender difference at such a young age? And what are the problems that we can see? What are some of the barriers in terms of the difference of time use at a very young age for between paid work for girls and boys.

Prof. Latif Dramani: Yes. Would you like me to answer?

Aïssata Fall: Yes. Go ahead and then I will follow up with the other questions after.

Prof. Latif Dramani: Yes. Thank you. Aïssata. What we see from the results of our analysis, and we’ve been working with all the different national representatives from the countries that we’re working with, to maybe also, give us some way in as to explanations. How do we explain this? Is it because in many of our countries, we have observed that there is this difference, starting at a very young age, especially in the countries we’ve observed this, and we see a very a different set of very young age between young girls and young boys. And this is probably most likely due to social norms and cultures. There are certain domestic activities that girls do that boys don’t do. And this is just something that is hardwired into social norms, if you will, that women have, work that they do a household work that is expected of women. So, I think that this is probably what really explains it, this division of labor that we see at a very early age because of social norms. So, I think it’s mostly socialization in the various countries. Then we can also see that when we look at countries in the Gulf region, for example, that changes quite a bit. There are differences, but they’re not quite as marked. And this is this is the answer I can provide as of now. But we have asked for the different country teams that have been doing the NTA and the NTTA. We’ve asked them to also consult with sociologists who can help give a shed light on this phenomenon that we’re observing and give us more explanation, because this is something that we do see quite clearly in many countries. It’s not something that we see that changes really from one country or one analysis to another. This is something that we really see that in every country across these this region and so I will stop there. But I that is my answer.

Aïssata Fall: Thank you very much. Let me take a second question now.

What is the strategy that could be implemented in order to urge our states to change these trends? We have talked about investing more in education and in health, but nothing is happening. What can we do to what strategies can we use to really pressure our governments to make these changes?

Prof. Latif Dramani: Would you like me to answer? Is it good?

Aïssata: Yes. Go ahead please.

Prof. Latif Dramani: Well, I think that one of the main things we see is that we have to, first of all, get the results more widely disseminated because we see often that our ministries, this is not something that people are talking about. It’s not being analyzed in terms of the state budget, It’s awful. Often looked at just at the growth rates. The budget is growing and it’s being looked at from that point of view. But it’s not necessarily looking at how this impact is affecting the budget. And often this is what the politicians are looking at, the minister is saying, well, we get a little more money, so we’ll give a little bit more money to health or if we get a little bit more money or money, rather, we can give a little more money to the health sector. But in terms of structural changes, things are not really changing much. So I think that we need to, first of all, start analyzing this from a structural point of view, looking at the structures, because in terms of our budgetary policies. Things need to be trending upward in terms of our structural policies, but you have to look at whether you’re investing 10%, 5%, 25% and that and then if there is a growth rate, you have to look at it and say, why are we seeing budget growth? Because unless there are budgetary shocks such as crises, wars or so forth, all the aggregates are generally on an upward trend over time and this is because social demands, the basis is growing, the population is growing. And so the needs that have to be a matter also growing. So if we don’t look at the structure, if we look at only growth rates, which is often what we do then we’re not going to be able to really implement these changes. We have to change the way we analyze it. And ministries and the sectoral departments and regional departments have to look at how this is impacting the budget. Because if you look at a certain sector and if they don’t have sufficient resources, it’s going to fail. So often it’s because they haven’t been given the resources, they need to do the work that needs to be done. So in health or education, if they don’t have the resources, if we want to make progress, we have to have a clear basis and we have to have a good structure in place.

And then once we have these structural policies in place, then we can look at how things are progressing and how we are improving public expenditures.

Thank you.

Aïssata: Thank you. For people who had posted questions, I am sorry, but we have a lot of questions, and we don’t have a lot of time left. So, some questions are more country specific. Why Senegal invests this or why Mauritania doesn’t invest that and so forth. So rather than discussing individual countries now, we will provide answers by in writing after our webinar. But we are going to try to look at some of the more general questions today.

I think this important for us to look at issues of. And this is a question in English it says, how can this information be used for advocacy and what are the desired outcomes over the long time? So these are the types of questions we would like to ask of our panelists today who I’m going to introduce shortly. But the other questions, we are not going to forget the other questions. And we will provide answers after. But what I can say for now is that, yes, these results are in tools are publicly available and they are intended to be meant by or intended to be used by governments and policymakers. This is the fruit of about ten years of work. But these are tools that are now newly being used in the budgeting and planning, uh, areas. And we’re trying to see how social sectors can not only use these results, but also use these mechanisms to better understand these budgeting processes. And this is of course related to the quality of the data and how the data is being used. For me, in terms of social protections and demographics, I think that the use of these tools and these results is useful because these are tools that are going to help governments have concrete tools to help better plan their budgeting processes. But it’s also a way to validate the work of technicians, researchers who have validated these tools as being effective tools. And by usin the data that we have, we will come back to these questions. We will provide answers in writing after the webinar, as I said, but we don’t have a lot of time left. So I would now like to continue with the next section of our webinar. And we will have a roundtable discussion with four people, who are directly involved in using this data. And they will be giving us their opinions about how useful this data can be and these tools for policies and decision making.

We have, first of all, Mariama Fanneh, who is a Director of the National Population Council in Gambia. She is with the office of the Vice President in the Gambia. In this role, she is responsible for coordinating the national population policy and programs, including the UNFPA funded country program. As Director, she also leads the National Observatory for the Demographic Dividend in The Gambia. Currently, she is a part time lecturer in public policy at the Management Development Institute, and her career includes positions such as Assistant lecturer in Management and Economics at the University of the Gambia and other schools. She’s currently pursuing a PhD in Public Administration at the University of the Gambia focusing her research on harnessing the demographic dividend through youth and women’s empowerment in the Gambia. She holds a Master’s degree in Business Administration from Clayton State University in Georgia, United States, and a masters in Population Studies from the University of Ghana, and she also has a bachelor’s degree in Economics, and she has also led significant research projects, including a national study on COVID 19 in The Gambia. And she’s worked on several initiatives related to youth and women empowerment.

Next, we have Pr. Germaine Anate, who is a full professor in information and communication sciences, and she is the director of the center for Studies and Research on Organizations, Communication and Education at the University of Lomé. She is a member of the National Assembly of Togo, and she has also served as Minister of Communication, Culture, Arts, and Civic Education. In addition, she is deeply involved in humanitarian and associated organizations. In this capacity, she chairs the Board of Directors of the NGO care solidaire, where she advocates for the empowerment and development of youth and women through, among other things, leadership training, communication techniques, and efforts to combat gender-based violence. She is also the president of the Togo Writers Association, and she’s published several articles, scientific works, and literary books.

Next, we will have from Burkina Faso, Dr. Larba Issa Kobyagda, who has a Ph.D. in economic sciences and a background as a financial economist. He has held strategic positions within the Burkinabe public administration for the past ten years, including at the Ministry of Economy and Development as a lecturer and assistant professor in economic sciences at Thomas Sankara University. He’s also a member of the research team on the global economic policy issues, and has authored several scientific publications on economic and financial policies. Dr. Larba, as Director General of Economy and Planning, is responsible for coordinating tools to support the effective management of the economy and development, as well as overseeing the monitoring and evaluation of public investments. Additionally, he serves as the coordinator of the National Observatory of the Demographic Dividend of Burkina Faso, where he conducts studies and research in generational economics, advocates for policy, and strengthens national capacities in monitoring demographic dividends.

And finally, from Mali, we have Mr. Moussa Sidibe, an agro-economist and local development expert, who is the national coordinator of the World Bank’s Sahel Women’s Empowerment and Demographic Dividend, or SWEDD project in Mali. Moussa Sidibe holds a degree in agricultural engineering and rural engineering from the Institute Polytechnique Royale from Göteborg in Mali, and a master’s degree in analysis and evaluation of agricultural, social, industrial and environmental development projects from the School of Economic Sciences of Rennes one, France. He has over 30 years of experience in social economic development, particularly in rural areas, working with NGOs and consultancy firms. He is conducted several expert missions for development partners in Mali, Africa and Europe, and since February 2016 he has been coordinating the SWEDD Mali project, which focuses on population issues, human capital, and particularly on women’s empowerment and the demographic dividend in the Sahel.

I am going to ask our panelists to turn on their cameras if possible. But I know that sometimes the connections don’t allow for your videos to be on. But so if you have the bandwidth and can turn on your cameras.

Great. I see, Dr. Larba and Professor Aneta. Moussa, are you able to turn on your camera? But if you’re not, that’s fine. No problem. And then I also see that we have Ms. Astou Diouf, who is a legal expert with degrees from the Cheikh Anta Diop University in Senegal. And she is currently the national director of Gender Equity and Equality since November 2019 at the Ministry of Family and Solidarity. With a rich experience of 19 years, she has held various leadership roles in the sectors of women, children, family and gender. She has worked in promoting women’s status, managing legal affairs, and directing programs related to gender equity and equality. As a national focal point for ECOWAS, she is played a key role in initiatives concerning women, peace, and security. Her career demonstrates a deep commitment to improving the living conditions of women and families through an approach focused on equality and social inclusion, and Miss Diouf holds a master’s degree in finance and public management, a master’s degree in defense, Peace and security, and a masters in Environmental law.

So I would like to start with our questions for the panelists, and I’d like to ask you to try to answer your questions in just 2 to 3 minutes. we have had a few connection issues, so we lost a little bit of time. So if you could be very brief with your answers, that would be great. So we’ll try to pretend as though we’re not in West Africa with the connection issues. And I don’t think anybody’s going to be too traumatized by the fact that we had some issues and are running a little late. But first of all, and before I ask my questions, I don’t know if everybody I don’t know if all the panelists can turn on their cameras if possible. Okay, great. Thank you. Now I see you all. Oh, for those who are able to.

To begin, I would like to ask this question to Mr. Larba from Burkina Faso, Miss Diouf from Senegal, and Miss Fanneh Gambia. And when we look at this process the BSDD and we see that it’s a long process and we’re looking at the demographic dividends and the final results. We have all these analyzes that we’re doing, the NTA, the NTTA so forth. And we’re also looking at the different indicators and the indexes that are allowing us to align these analyzes with the African Union roadmap. So I’d like to ask if you could explore the concrete impact and benefits. And can you provide some specific examples of how the BSDD has influenced your decisions and improved outcomes in economic development and gender equity?

So for Dr. Larba, Burkina Faso is rather advanced in this BSDD process. So can you maybe talk about which BSDD tool has most influenced your economic decisions and development? And if you look at how things were done in the past, how things have changed over time. Thank you.

Dr. Larba Issa Kobyagda: Thank you, Aissata, for giving me the floor. And thank you to all the other panelists for being here today. Thank you for to Professor Latif, for your great overview, which really gave us a good idea of what we can do from a technical point of view with the BSDD. I’m going to answer the question directly for Burkina Faso. Looking at population trends has always been a major priority. But of course, now with the tools that we have this has helped us better develop our strategies and we’ve been working with the CREG to develop our BSDD profile, which we did in 2018. This profile showed us that for the five different dimensions that are measured in this index, Burkina Faso did not achieve more than 50% in any of these different dimensions. And we see that we have a lot of work to be done in order to really capture the demographic dividends and to make more real progress. So this process was conducted looking at budget sensitive demographic dividends. And we were looking at how we could take economic shocks into account in our budgeting processes. And as we looked at the BSDD, we were looking at the country’s profile and so the BSD, the advantage is that it gives us more opportunities to look at expenditures and to see how we can better invest our public, our public funds into improving the wellbeing of our population.

It also helps us to analyze our budget from a functional point of view and also looking at the impacts of productivity of expenditures by different departments and sectors. And it also looks at efficiency issues and which expenditures have greater impact.

So these types of analysis have been difficult to do with the classic with the traditional budgets but when we look at the traditional budget up from 2017 up to 2020, when we look at the demographics, we see that efforts were done by countries. But these efforts didn’t necessarily take into account the different economic shocks that we sell in the various countries, and we saw that the proportions were relatively low in terms of investments in education and health. But there was a clear improvement in terms of the health investment from year to year.

And from 2.5 from 212, we tremendously increased from 2021 to 2023. And these, you know, are weak compared to what is really expected. So the country told itself, given its current, security crisis, it is good to intensify the use of BSDD, so that budget allocations in the favor of human capital may lead to better health. Now, when we examined budgetary flexibility in terms of the BSD process, we had effects. We saw different effects of these allocations in terms of health or education. Nevertheless, this means that the country has done a lot of effort to work for youth and the female population in agreement with the African Union efforts. So this means that we have been able to undertake a political dialog with the Directorate of Budget Institution, the National Assembly, etc. to take BSDD into account in the 2025 budget. So we look at these strategic choices that were documented in the multi-year budget document for 2024-2026. This BSDD is important and has been brought to the attention of the government. And so. We have had comments about the taking into account of BSDD. So the 2025 circular has taken into account BSDD as an innovation in the creation of the budget to implement in a progressive manner. So we’re talking about demographic transition and how to take advantage of the demographic dividend by 2025. And this is what we are working on to ensure that this instrument brings us a better solution to the things that concern young people and women.

Aïssata Fall: Thank you very much, Doctor Larba. Interesting. When you were talking about how the process made it so that you could highlight the efforts and broaden the political dialog so that for you, even within the government, this really enables you to do better advocacy work.

Miss Astou Diouf from Senegal, if you could talk to us about your opinion about how the process, the BSDD process had changed the national digitization culture within Senegal. We have participated in multiple sessions together. So we’ve talked about this. I would like to know, what do you think about this process and how it has changed the budget budgeting process in three minutes, please.

Astou Diouf: Thank you so much. Miss Fall and members of the panel. Yes. My mic is on. You can hear me.

Aïssata: Yes. Yes, we can hear you.

Astou Diof: Yeah and thank you to the CREG for your presentation. And then thank you for Burkina Faso there is moving in the right direction. And Senegal is working on establishing the means and ways to implement BSDD. And we want to see the methods of application for BSDD. Now in terms of structuration as a function of the budget we have. We are aware of the study published by CREG recently, Senegal. You know, if you look at the various functions human capital, economy, governance, etc.. There is a single dimension that is at 52% for us, it’s the human capital where we talk about the main levers of the demographic dividend for education and health, where 22%. So the figures that have to do with these various dimensions are important for us. And we were able to note an interesting trend between 2011 and 2019 in terms of performance. But given the things that have happened on the past few years with political tensions we are not certain that this trend has been confirmed. Um, the situation has led us to open dialog with various actors. Beyond the studies, we are communicating with this key sectors and we are also undertaking a series of advocacy efforts with the sectorial ministries, the parliament, civil society. And so these will be cooperation sessions that are going to be ongoing. Now in terms of budgetization, we feel this is a good opportunity to address indeed this this issue of the BSDD by and also in adhering to what is of most interest to us now in analyzing DDMI for Senegal, we saw that it remained very weak among women 35.4% among women in like 47% among men. So we have a lot to do, to catch up. And we are one of the countries that joined up with SWEDD project and so we want to pursue the ongoing objectives to really undertake BSDD. So this means that we must raise awareness among policymakers and also we must increase capacity build among the various actors. And this is where the CREG does a lot of work with to enable us to put in place BSDD and to really reduce inequalities between the genders.

Thank you.

Aïssata Fall: What’s interesting is, once again, we are hearing that BSDD is an interesting objective to really improve and optimize public expenditure. It is a reading of budget programing. It is a different reading of budget programing in terms of DDMI and this other dimension that enables us to look at what’s going on in our countries in a different way. And it’s really, it’s been a new way of thinking about things and the ability to do this internal advocacy for it to have more effective public expenditure.

Um, Miss Mariama from Gambia. Can you hear me? Your camera is off. But thank you. I would like to know. So. Gambia. The Gambia undertook the first steps the NTA profiles. I know you are undertaking a study, an investigation on the use of time in order to create an NTTA profile, and I would like to know your opinion as to why The Gambia is undertaking this process. And you know what do you think of it in terms of the you in comparison to the usual practices? And what are you hoping to achieve from this? What are your expectations? Thank you.

Mariama Fanneh: Thank you very much. Thank you to CREG and PRB for the opportunity to attend this. Um, I don’t know whether I’m.

Aïssata Fall: The sound is very very weak.

Mariama Fanneh: Is it still very weak or is it okay?

Aïssata Fall: Is it okay for translation interpreters? Okay. Go ahead Mariama.

Mariama Fanneh: Okay. Thank you very much. Thank you very much CREG and PRB for the opportunity to attend this important webinar, which is key for building the capacity of technicians and getting the support of policymakers. I hope this is something that you’ll be organizing often. Regarding, why we want to apply the BSDD process and why we want to continue ensuring that the Gambia harness the demographic dividend. The reason for wanting to apply the BSD process is because the Gambia now stands the pivotal moment when it comes to harnessing the demographic dividend. Uh, because when the demographic dividend profile of The Gambia was updated, we realized that we have a steep increase in our potential for harnessing the demographic dividend. And also following the updating of our BSDD profile, we also developed the demographic dividend monitoring tools. And this we did with technical support from CREG through the World Bank project, which is the SWEDD Plus. So we develop the BSDD like Professor Dramani, he was explaining. And these are tied to the four pillars of the AU for harnessing the demographic dividend. We have the profile ready and we also have the DDMI, which is the diagnostic tool. But it was very unfortunate that at the time of developing the NTA, we couldn’t develop the NTTA because we didn’t have the data on time use but we are currently working on that because we know women contribute a lot when it comes to the GDP, but it goes undocumented. And we want to know how much women are contributing when it comes to the GDP.

Currently in the Gambia, Aïssata, it’s very difficult for us to be able to harness the demographic dividend because of the budgeting system that we have, which is the traditional budget. And we know that for the traditional budgeting approach, it’s mostly about maintaining fiscal balance and allocate funds based on past spending. And it’s also addresses immediate needs without considering long term demographic trends. For instance, when Professor Dramani was explaining, my mind went to, um, you know, um, what happened last year with the budget and that is how I’m sure a lot of countries that are budgeting based on the traditional, system of budgeting, that is how they budget, because for last year’s budget when it comes to education and health for education, it was 37.3%. And for health, it was 17.1%. And when it comes to youth empowerment and employment, it was 0.01%. And we know that for a country to harness the demographic dividend, especially for a country like the Gambia, where you have 79.2% of the population below the age of 35, and we’ve also have had a decline in child dependency between 2013 to 2022. Our child share dependency declined by 10%. And we know that that is one of the prerequisites for the opening of the window of opportunity for addressing the demographic dividend. Going back to the numbers that I just mentioned, 37.3% and 17%. Yes, that is the percentage of the budget that goes to health and education. What are they going into service provision? No. Most of our budget goes to recurrent expenditure. So in having a DD sensitive budgeting we’ll be able to know what is going well, what is going to service provision and also what is going to a recurrent budget, because we know that we recurrent with most of our funding going to recurrent budget might be impossible for us to harness the demographic dividend, knowing that the current opportunity will not last forever. It’s expected to peak in 2035 and close by 2050, depending on the DD profile.

The demographic dividend is also not automatic, and we know that is the potential that must be harnessed for economic growth and development. Therefore, I think it’s very, very important for us not only to also go ahead and do a time use survey and develop the entity profile for the country to know women’s contribution to the GDP. But it’s also a very, very important for us to have a budget that is really responsive to the demographic dividend, a budget that is conducive to harnessing the demographic dividend, and that is the DD sensitive budgeting. And we’re looking forward to really getting the support we able to transform our budget into our budget that is sensitive to the demographic dividend. Thank you all very much for your kind attention.

Aïssata Fall: Thank you very much, Miss Fanneh. It’s very interesting to hear what you were explaining about the classical manner of establishing a budget, and to into relying on recurring expenses last year’s budget, without wondering how does this contribute to the various dimensions and the objectives that are necessary in order to take to benefit from the demographic dividend, without also wondering whether these expenses contribute or make use of the demographic dividend? You know, and having zero invested in youth when you have such a young population is very striking. So I would like to speak a little bit about how this process started and how the countries integrated the various questions and challenges in their budget.

And now I’ll talk to Pr. Germaine Anate, Togo, so you are in the National Assembly, which he has not necessarily been involved in this work in the beginning because it’s a very technical type of work. But the tools are here, and in the end, it is the National Assembly that must approve the budgets, that must support policies that will strengthen efforts to take advantage of the demographic dividend. So for you, what are the specific roles of the gender dimensions and what role do they play in your budgeting process and your decision making process at the National Assembly? And how can BSDD help us to help you to deal with this, these issues of gender equity. You have the court, you have the floor.

Germaine Anate: Thank you for having inviting me to participate. You spoke about the fact that the process has been very long. And forTogo, we must say that the opportunity we had is that in Togo we had a gender sensitive policy. We also had a budget program that included pretty early on the gender issue and this has improved over time. And so the current version that is being finalized, it includes this. So this has been mainstreamed throughout all the various ministries and institutions. And it has taken into account in the 2025 budget, which is being finalized. And so Togo, you know, is taking advantage of the fact this mainstreaming of this issue in its budgeting and to take advantage of the demographic dividend. And really, this is something that’s been accomplished because the draft budgets are currently being created and this dimension has been included in it you know and and I mean, so in term we’re going to allocate amounts to every action activities and taking into account gender and demographics.

Next, I would say that the gender dimension has an essential role in the budgeting process in Togo, especially given the National Gender policy that has been put forth, and that establishes gender units within each ministry. And Togo is also working on gender equity and the empowerment of women. So in terms of strategy, this gender dimension is already taken into account. And to really enable all levels of the population to participate and benefit from development. This effort was undertaken in 2020, integrating gender into the budgeting process. I am not going too long on the budgeting issue, but we must recognize that, you know, during the budget cycle, yes. We have included the gender dimension you know, in terms of the budget, audit, etc.. And but we must say also that BSDD data is taken into account in the improving of budgeting that is sensitive to gender and in terms of the specific role of the gender dimension. For me, it’s really a function of facilitation and a translation of public policy, because it is particularly about facilitating and making sure that the budgeting process is inclusive throughout all its steps, and to ensure that women are direct beneficiaries of budget allocations that have been justified by supported by these criteria. And, you know, in my position when we, we look at the line item that is dedicated to gender to make sure that the allocation is there and that it is what it should be and that it is not actually used for something else. So there’s this role of facilitation, and we need to also monitor the governmental policy.

[The interpreter apologizes. She cannot hear the speaker anymore.]

So for a parliamentarian, this is very important because we monitor government activities. So we, you know, taking this into account to have a more aware review of what’s going on when we are asked to review the state’s budget. So in Togo, the BSDD is really going to enable us to strengthen this gender issues to reduce inequalities, and particularly in terms of investments for young people and for young women, young girls, and also for health care. And let’s recall that Togo joined the project for the Empowerment of Women and for the demographic dividend in sub-Saharan Africa and one of the results of this study is BSDD. So this is what I have to say.

Aïsatta Fall: Thank you so much, one certain women must be the beneficiaries of allocations for which they serve as a pretext and this is a very important topic, you know, because to budget for gender is one thing. Budgeting for women. Yes. But what is the impact and how do you monitor the efficiency, the effectiveness of the allocations, the effectiveness of the policies. So this is a tool that enables us to do this progressively. But also to analyze these policies in a different way. Uh, thank you very much Honorable Anate.

Moussa Sidibe from Mali, you are next. Could you talk to us about what are the assets, what are the challenges associated with BSDD at this current time, especially for the improvement of social sector planning? You know, this has to do with finance, budgets, taxation, etc. You know, we have had research in economics, demographics which and then tying this to planning needs. So budgeting is not just within the Ministry of Finance. You know the ministry; it the ministry must understand how the social sectors function. And so for you, what are the advantages and disadvantages of BSDD?