American Attitudes About Poverty and the Poor

Date

May 30, 2002

Author

Focus Area

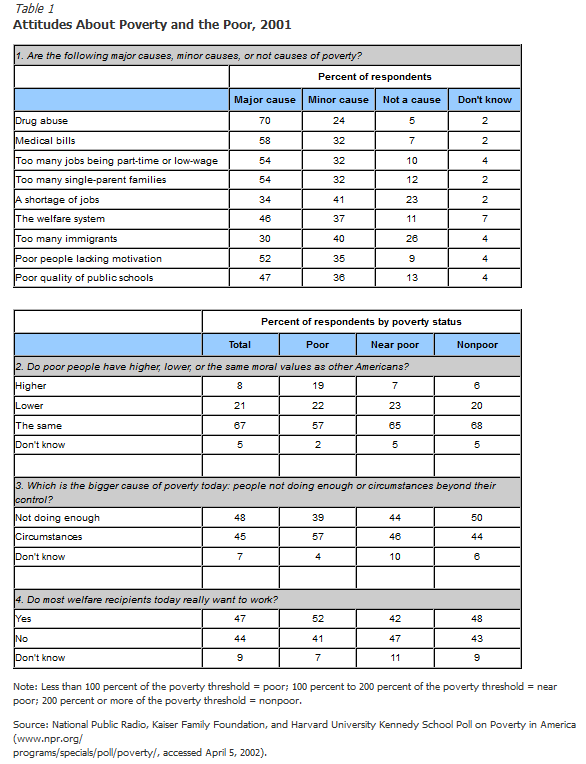

In early 2001, a national poll conducted by National Public Radio (NPR), the Kaiser Family Foundation, and Harvard University’s Kennedy School asked nearly 2,000 Americans 18 or older, “Which is the bigger cause of poverty today: that people are not doing enough to help themselves out of poverty, or that circumstances beyond their control cause them to be poor?” Respondents were roughly equally divided between “people not doing enough” (48 percent) and “circumstances” (45 percent), as shown in Table 1. About 50 percent of the more affluent people polled believed that the poor were not doing enough to help themselves, but so did about 39 percent of the poor. The poor were more likely to blame “circumstances” than themselves for their financial hardship.

The poll also showed that about two-thirds of Americans believe that the poor have the same moral values as other Americans. But about one-fifth thought the poor had lower moral values. The poor themselves share this belief: About one-fourth believe the poor have lower moral values than other Americans. Even with work-based welfare reform, a sizeable share of the American public holds unfavorable views about poor people.

Hard Work and Motivation

One persistent stereotype is that the poor, especially the welfare poor, are unmotivated: They lack aspirations to “get ahead,” or don’t work hard enough to succeed. The NPR/Kaiser/Kennedy School poll, in fact, showed that 52 percent of the American public believed that lack of motivation was a major cause of poverty; another 35 percent believed it was a minor cause of poverty. Differences in responses by poverty status were surprisingly small. Most Americans, including the poor, said they strongly believe that America is a land of opportunity. Their responses suggest they believe that motivation and hard work can pull people out of poverty, regardless of their background.

Other studies of the poor typically reveal that values among the poor are remarkably similar to those of the rest of society. A study in Milwaukee showed that most teens, including teenage mothers, regarded education as being valuable for its own sake, as a source of personal pride and as an example for their children, as well as a route to upward economic mobility.1 But people in poverty often fail to translate educational values into concrete goals, in part because they do not know about or have access to local educational resources, or because those resources are limited or difficult to reach.

Surveys also indicate that the poor prefer work to receiving help from the government or from family members. The NPR/Kaiser/Kennedy School poll, in fact, showed that 52 percent of poor people believed that “most welfare recipients today really want to work.” Work provides purpose in life, a place to go, a sense of control, and income. For many low-income people, however, jobs are often unavailable; if available, they often pay poorly or do not provide health insurance. To make ends meet, many people in poverty rely on public or familial assistance. According to researchers Kathryn Edin and Laura Lein, the poor often require “something special” in order to find and keep a job, such as low rent, free child care from a relative, help with bills, a reliable car, good public transportation, or a generous benefactor.2

Poor women tend to dislike or disapprove of welfare; they “hate it,” “don’t want it,” “hope [to] never have to be on it,” and “want to get off it.”3 Some studies have shown that the poor believed they are entitled to cash assistance if they experience economic need, but that very few approved of welfare receipt per se.4 Welfare mothers often feel degraded, and resent the public view that they are lazy or avoid work, even as they maintain a home and raise their children. Most women value their ability to combine work, welfare, and family support, and to use welfare while improving their job prospects. But many poor people distrust the government policies and programs that were ostensibly designed to help them.5

Daniel T. Lichter is professor of sociology and the Robert F. Lazarus Chair in Population at Ohio State University. Martha L. Crowley is a doctoral candidate in the sociology department at Ohio State University. This article is excerpted from PRB’s Population Bulletin,“Poverty in America: Beyond Welfare Reform” (PDF: 1.2MB).

References

- Bonnie Thornton Dill, “A Better Life for Me and My Children: Low-Income Single Mothers’ Struggle for Self-Sufficiency in the Rural South,” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 29, no. 2 (1998): 419-28; and Roberta Rehner Iversen and Naomi B. Farber, “Transmission of Family Values, Work, and Welfare Among Poor Urban Black Women,” Work and Occupations 23, no. 4 (1996): 437-60.

- Kathryn Edin and Laura Lein, Making Ends Meet: How Single Mothers Survive Welfare and Low-Wage Work (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1997).

- Iversen and Farber, “Transmission of Family Values, Work, and Welfare Among Poor Urban Black Women.”

- Robin L. Jarrett, “Welfare Stigma Among Low-Income African American Single Mothers,” Family Relations 45 (1996): 368-74.

- Dill, “A Better Life for Me and My Children: Low-Income Single Mothers’ Struggle for Self-Sufficiency in the Rural South”; Kathryn Edin, “The Myths of Dependence and Self-Sufficiency: Women, Welfare, and Low-Wage Work,” Focus 17, no. 2 (1995): 1-9; and Jarrett, “Welfare Stigma Among Low-Income African American Single Mothers.”

">

">