Toshiko Kaneda

Technical Director, Demographic Research

Families face the financial burden of paying out-of-pocket for care not covered by Medicare and Medicaid and the emotional toll of day-to-day caregiving.

Today, an estimated 7.2 million Americans ages 65 and older live with dementia. While conversations around dementia often evoke nursing homes, most older Americans living with dementia are actually aging in place in their homes. Home-based care has become more common over the last decade, partly because it is more affordable and aligns with what many people prefer.

People living with dementia often face both medical and practical barriers to obtaining care, including challenges with memory, decision-making, and mobility. These difficulties make access to effective care at home not just helpful but essential to supporting their ability to remain safely in the community.

Despite its benefits, home-based care is not without challenges, including the financial burden of paying out-of-pocket for services not covered by Medicare and Medicaid and the emotional toll on family members who often take on day-to-day caregiving responsibilities. Understanding how home-based care works for the growing population of older adults with dementia is critical for improving how dementia is managed in the community and providing better support for older adults and their families.

Home-based care typically falls into two categories: home health care and home care. Home health care refers to medical services provided by licensed professionals, including skilled nursing care, physical therapy, and medical social services. It is covered by Medicare if prescribed by a doctor or nurse practitioner. Home care refers to non-medical services to assist with housekeeping and the activities of daily living, such as bathing and dressing. Medicare does not cover home care unless it is provided with medical care, but Medicaid covers home care in some states.

Based on data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) and Medicare claims between 2012 and 2018, Julia Burgdorf and her colleagues found that approximately 30% of home health care users had a dementia diagnosis.1 Older adults with dementia were twice as likely to use home health care compared to those without dementia.

About half of those with dementia were referred to home health care without a preceding hospitalization, compared to slightly less than a third of those without dementia. This finding highlights the importance of home health care as a key source of clinical care for older adults with dementia, not just for recovery care, Burgdorf and her colleagues said.

Once enrolled in home health care, people with dementia received care more times (an average of 1.4 times compared to 1 time) and for longer periods (median of 56 versus 40 days) than people without dementia. They were also more likely to receive personal care, medical social work, and speech-language pathology services than those without dementia.

However, among people who received services, those with dementia had fewer visits for skilled nursing and physical therapy, the researchers found.

“Existing prospective payment structures incentivize HHC providers to limit the number of visits in order to lower costs and maximize profits,” they wrote. And “the 2020 implementation of a new Medicare HHC payment model, the Patient-Driven Groupings Model (PDGM), may further incentivize limiting visits for people living with dementia.”

The new payment model aims to reimburse providers based on how sick patients are—but it doesn’t directly account for dementia status, Burgdorf and team note. It also reduces reimbursement for community referrals, though many people with dementia enter care this way. Differences in coverage between Medicare Advantage (private plans) and fee-for-service (the traditional government-run plan), along with workforce shortages and fragmented care systems, may create additional barriers for people with dementia, they explain.

Burgdorf and colleagues suggest several ways to improve home health care for people with dementia, including:

Many older adults end up paying for home care out of pocket because long-term care is not included in Medicare, Medicaid coverage is inconsistent across states, and few people have private long-term care insurance, according to another analysis.

“The financial burden of out-of-pocket payment for home care is significant, particularly among people with dementia and those with limited income and wealth,” conclude Karen Shen and colleagues, who used Health and Retirement Study (HRS) data (2002-2018) to measure the financial burden of home care.

Home care also often results in ongoing expenses over a long period of time, unlike most other health care costs, they found.

In recent years, people with dementia made up one-third of an estimated 3 million people who received home care and almost half (45%) of the over 600,000 people who paid for at least some of this care out of pocket, according to the researchers.2 Among those with dementia who paid out-of-pocket, half (51%) spent over $1,000 per month, compared to one-fourth (26%) of those without dementia. Additionally, people with dementia were much more likely to pay for full-time help, defined as 40 hours or more per week, compared to those without dementia (46% versus 22%).

Although higher-income individuals are more likely to pay out-of-pocket, many people with lower incomes also do so, largely because those with fewer financial resources are disproportionately affected by disability and dementia, the authors note. In fact, about half of those paying for home care out of pocket were poor or near-poor, defying the common perception that private home care is used only by individuals with higher incomes.

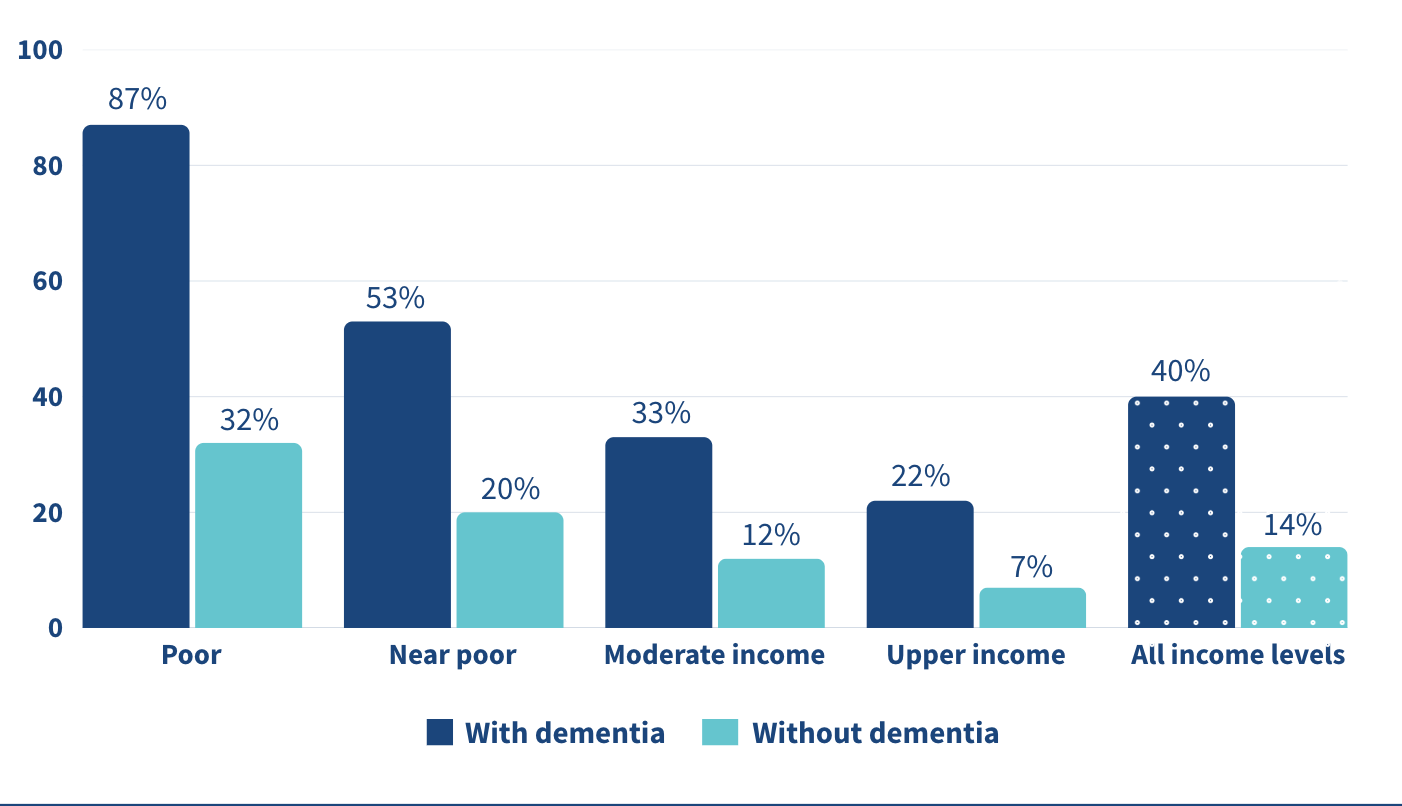

Those who are poor and have dementia experienced disproportionate financial burdens, as they spent 87% of their household income on home care, compared to 32% spent by their peers without dementia, and 22% spent by high-income individuals with dementia (See figure).

These findings suggest that those with dementia and limited financial resources may not be getting the care they need.

“Policies aimed at easing the financial burden of home care are essential, particularly for low-income individuals with dementia who experience the greatest financial burden,” argue Shen and her colleagues.

They recommend policies to reduce unmet care needs and financial hardship while also making the system more equitable and responsive to the realities of aging at home with dementia, including:

To make these programs financially sustainable, they recommend targeting benefits to the most vulnerable individuals and incorporating cost-sharing mechanisms so that those with more resources help shoulder the cost of care.

Note: “Poor”: 100% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL); “Near-poor”: 100-200% of FPL; “Moderate-income”: 200-400% of FPL; and “Upper-income”: >400% of FPL.

Source: Karen Shen et al., “Paying for Home Care Out-of-Pocket Is Common and Costly Across the Income Spectrum Among Older Adults,” Health Affairs Scholar 3, no. 1 (2025).

Even with paid home care, most dementia care still falls on family and friends. In the United States, over 11 million unpaid caregivers provide over 15 billion hours of dementia care every year, according to Yeunkyung Kim and his colleagues.3 One way to give caregivers a break is through respite care—short-term care that lets family members step away for a few hours or days. Ultimately, respite care aims to help sustain caregiver health and delay the institutionalization of the people in their care.

Yet its use remains limited. Only 16% of Black caregivers used respite services compared to 32% of white caregivers in 2015, representing a significant gap of 12 percentage points, Kim and team found. Although this racial gap had been reduced or eliminated by 2017, respite care use remained low among both Black and white caregivers. Data are from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) and the National Study of Caregiving (NSOC) from 2015, 2017, and 2021.

Even though there have been efforts to expand access, too many caregivers are still doing this difficult work without enough support. This highlights the persistence of structural and informational barriers to care—including financial cost, lack of awareness, cultural expectations, and insufficient supply of respite providers.

The underuse of respite care represents a missed opportunity to support the mental and physical health of caregivers, and thereby also the stability of dementia care at home.

Kim and colleagues recommend several strategies to improve access to respite care for families supporting older adults with dementia, including integrating respite services more fully into long-term care systems, particularly through expanded support in Medicaid-funded programs like home- and community-based services waivers.

Better outreach and clearer communication could also raise awareness of available services, since many caregivers remain uninformed or face fragmented information, the researchers note. There is a clear need for more flexible respite options that can accommodate the diverse cultural, financial, and scheduling needs of caregivers. For example, offering evening or weekend respite hours for those who work during the day, or providing in-home options for caregivers who are uncomfortable with facility-based care, could make a meaningful difference.

Simplifying program design, reducing waitlists, and ensuring consistent availability are also key to increasing use of these services, they said.

1. Julia G. Burgdorf et al., “Variation in Home Healthcare Use by Dementia Status Among a National Cohort of Older Adults,” The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 79, no. 3 (2024).

2. Karen Shen et al., “Paying for Home Care Out-of-Pocket Is Common and Costly Across the Income Spectrum Among Older Adults,” Health Affairs Scholar 3, no. 1 (2025).

3. Yeunkyung Kim et al., “Trend in Respite Use by Race Among Caregivers for People Living With Dementia,” The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 79, Supplement 1 (2024): S42-S49