Paola Scommegna

Contributing Senior Writer

Life expectancy differences between states have widened in recent years, says new analysis of U.S. Mortality Database.

January 12, 2023

Contributing Senior Writer

Former Research Associate

Research Analyst

People in U.S. states with more liberal policies can expect to live longer than their peers in states with more conservative policies, thanks in part to laws on minimum wages, tobacco taxes, gun safety, and the environment, according to new research.

Life expectancy differences among states have widened in recent years, as state policies have become more polarized. In general, states where policies have become more liberal have added years to their residents’ lives more quickly, while states where policies have veered conservative have seen slower gains in life expectancy, finds research led by Jennifer Karas Montez of Syracuse University.1

“The chances that an individual can live a long and healthy life appear to be increasingly tied to their state of residence and the policy choices made by governors and state legislators,” says Montez.

The research team examined life expectancy and policy change between 1970 and 2014 by merging annual data from the U.S. Mortality Database with annual data on 135 state-level policies scored on a liberal to conservative scale.2 A liberal policy was defined as expanding state power for economic regulation and redistribution or for protecting marginalized groups, or restricting state power for punishing deviant social behavior; a conservative policy was defined as the opposite. For example, a high minimum wage would be categorized as a liberal policy, while low corporate taxes would be conservative.

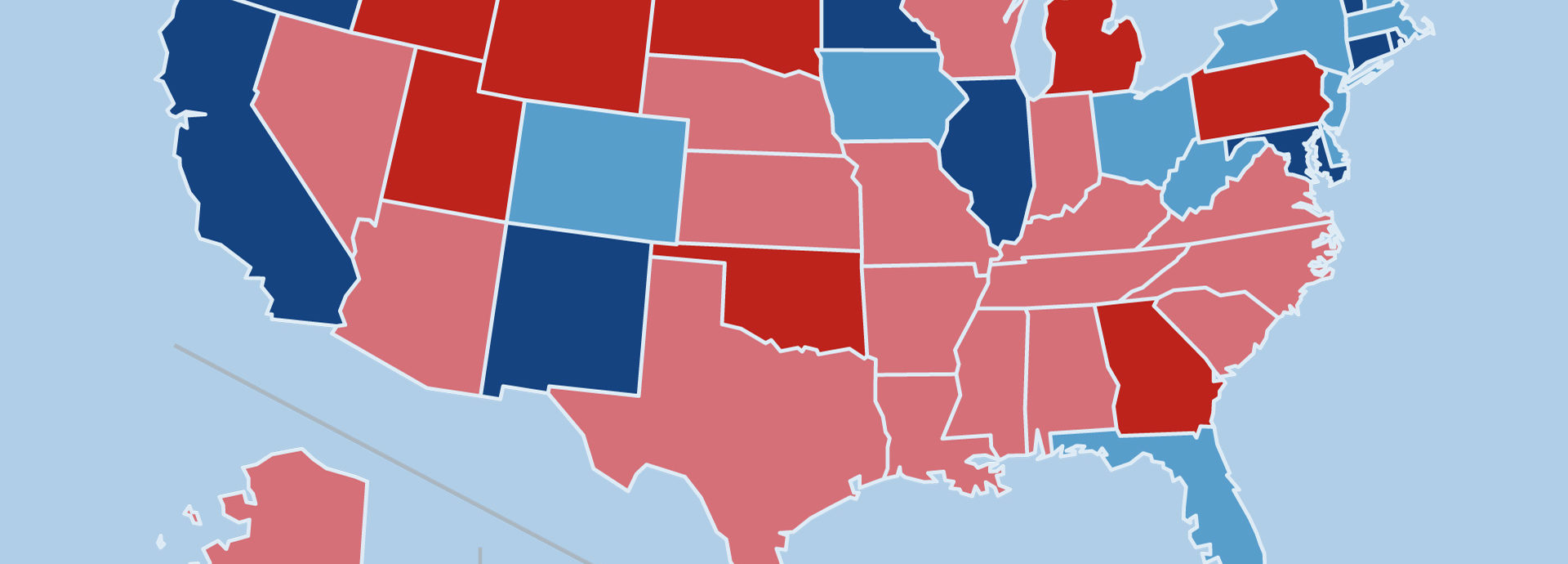

State policy movement to the right (more conservative) and left (more liberal) since the 1980s, and particularly since 2010, may have affected the life expectancy of residents, the analysis found. States that enacted more conservative policies were more likely to see their life expectancy gains slow, stagnate, or even decline in recent years, compared with states with more liberal policies. Overall, state policies became more polarized over the 44 years studied (see Figure 1).

Sources: Jennifer Karas Montez et al., “U.S. State Policies, Politics, and Life Expectancy,” The Milbank Quarterly 98, no. 3 (2020): 668-99; Jacob M. Grumbach, “From Backwaters to Major Policymakers: Policy Polarization in the States, 1970-2014,” Perspectives on Politics 16, no. 2 (2018): 416-35; and U.S. Mortality Database, University of California, Berkeley.

A striking example can be found in the case of Oklahoma and Connecticut (see Figure 2). The two states had identical life expectancies (71.1 years) in 1959. But between 1980 and 2019, life expectancy rose by just 2.5 years in Oklahoma (to 76.1), compared to a 5.9-year jump (to 80.8) in Connecticut. Oklahoma has seen an increasingly conservative policy environment, whereas policies in Connecticut have become more liberal.

Sources: Jennifer Karas Montez et al., “U.S. State Policies, Politics, and Life Expectancy,” The Milbank Quarterly 98, no. 3 (2020): 668-99; Jacob M. Grumbach, “From Backwaters to Major Policymakers: Policy Polarization in the States, 1970-2014,” Perspectives on Politics 16, no. 2 (2018): 416-35; and US Mortality Database, University of California, Berkeley.

If all states enjoyed the health advantages of a state like Connecticut, U.S. life expectancy would be on par with other high-income countries, according to the study’s analysis. While Oklahoma’s life expectancy in 2019 ranked near Croatia, Turkey, and the Czech Republic, Connecticut’s ranked among the Netherlands, Ireland, and Australia.3

An important driver of policy polarization in the United States is a shift in the way laws are made. The devolution of policymaking authority from the federal to the state level has opened the door for diverging policies, as states have gained more discretion over programs like welfare and Medicaid.

As policies have diverged, so have life expectancies. In 2019, the range in state life expectancy grew to 7.1 years—up from 5.5 years in 1959 (see Figure 3). That year, Hawaii had the longest life expectancy (81.8 years), while Mississippi had the shortest (74.7 years).

Sources: Jennifer Karas Montez et al., “U.S. State Policies, Politics, and Life Expectancy,” The Milbank Quarterly 98, no. 3 (2020): 668-99; and U.S. Mortality Database, University of California, Berkeley.

A related study by Montez and colleagues found that more conservative marijuana policies and more liberal policies on the environment, gun safety, labor rights, economic taxes, and tobacco taxes were related to lower mortality in working-age Americans between 1999 and 2019.4 In particular, gun safety laws were associated with a lower suicide risk among men, labor protections like minimum wage and paid leave were tied to a lower risk of alcohol-related death, and tobacco taxes and economic taxes were linked to a lower risk of death from cardiovascular disease.

Marijuana restrictions were the only conservative policies associated with lower mortality, specifically from suicide and alcohol-related causes, the study found. Montez notes that while marijuana can provide pain relief, it also has been linked to an increased risk of developing problem drinking, depressive disorders, and schizophrenia, as well as a higher risk of motor vehicle accidents and suicide.5

Had all states enacted the most liberal policies, 171,030 lives might have been saved in 2019, the study estimates. On the other hand, enacting the most conservative policies might have cost 217,635 lives.

“The decisions being made in state houses are increasingly having life and death consequences for working-age Americans,” Montez said. “Much of the narrative about the rising death rates of working-age Americans has pointed to opioid manufacturers and businesses leaving certain parts of the country. Our analyses points to another major player, and that’s state policymakers.”

About the U.S. Mortality Database: Released in 2018 and updated annually, the U.S. Mortality Database (USMDB) provides mortality data by sex for U.S. geographic areas (all Census Divisions, Census Regions, States, and Washington, D.C.) for all years since 1959 and for counties since 1982. The series were constructed from natality and mortality data distributed by the National Center for Health Statistics and population data from the U.S. Census Bureau, using the methods of the Human Mortality Database (HMD) for Census regions, divisions and states, and Bayesian inference for the counties.

Access is free and the data can be downloaded following a short registration process. Initially funded by the National Institute on Aging and currently supported by various sponsors, including the University of California, Berkeley Center on the Economics and Demography of Aging and the Society of Actuaries, the USMDB is managed by the HMD team at the University of California, Berkeley.

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging and conducted by a team of researchers including Jason Beckfield, Harvard University; Derek Chapman, Virginia Commonwealth University; Julene Kemp Cooney, Syracuse University; Jacob M. Grumbach, University of Washington; Mark D. Hayward, University of Texas at Austin; Blakelee Kemp, University of Nebraska-Lincoln; Huyseyin Zeyd Koytak, Syracuse University; Nader Mehri, Syracuse University; Shannon M. Monnat, Syracuse University; Steven H. Woolf, Virginia Commonwealth University; and Anna Zajacova, University of Western Ontario.

[1] Jennifer Karas Montez et al., “U.S. State Policies, Politics, and Life Expectancy,” The Milbank Quarterly 98, no. 3 (2020): 668-99.

[2] Jacob M. Grumbach, “From Backwaters to Major Policymakers: Policy Polarization in the States, 1970-2014,” Perspectives on Politics 16, no. 2 (2018): 416-35.

[3] Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), “Life Expectancy at Birth.”

[4] Jennifer Karas Montez et al., “U.S. State Policy Contexts and Mortality of Working-Age Adults,” PLOS One, 17, no. 10 (2022).

[5] Karas Montez et al.