Paola Scommegna

Contributing Senior Writer

Experts point to key dynamics challenging policymakers, health care planners, and families

August 6, 2025

Contributing Senior Writer

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

Early onset chronic disease, a growing caregiving gap, and climate change are among the major trends affecting the health and well-being of older Americans and their families, according to leading scholars from across the country.

Before a standing-room-only crowd at the 2025 meeting of the Population Association of America in Washington, D.C., experts identified seven key themes that are challenging policymakers, planners, and families as the U.S. population rapidly ages.

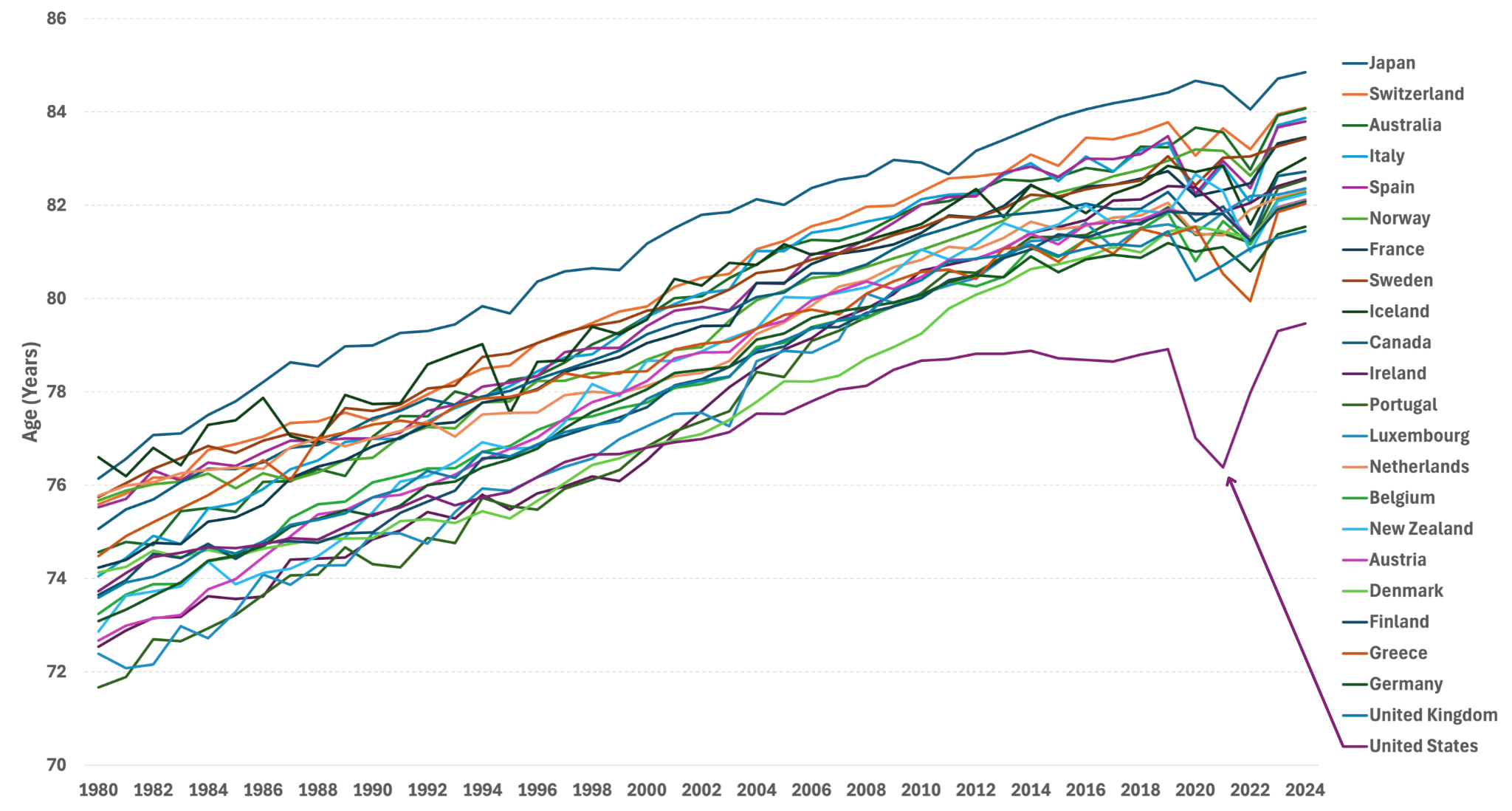

The United States has experienced the earliest and greatest slowdown in life expectancy improvements among higher-income countries, reported Eileen Crimmins of the University of Southern California/University of California-Los Angeles Center on Biodemography and Population Health.

“We have horrible life expectancy—and it’s getting worse and worse,” she said, pointing to the diverging line for the United States in Figure 1. Though premature deaths from heart disease and stroke have declined, Americans today are unhealthy for a longer portion of their lives, coping with chronic diseases and conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, cancer, and heart problems.

While we “have a long way to go” to improve the health of the U.S. population, Crimmins said, new research into biomarkers gathered through blood and other medical tests is offering clues into what speeds up or slows down the aging process, including stress levels, income, and social connections over a lifetime.

Source: United Nations, World Population Prospects.

While advances in health care have succeeded in preventing many early deaths, older people are spending more time living with chronic diseases today than two decades ago, Crimmins’ forthcoming research shows. Americans spent more years after age 65 living with diabetes, cancer, heart disease, arthritis, and high blood pressure in 2018 than in 1998, she has found.

Scott Lynch of the Duke Center for Population Health and Aging agrees. Over the past century, complex chronic conditions like cardiovascular disease and cancer have replaced infectious diseases like pneumonia and tuberculosis as the leading causes of death, he noted. In addition to biomarker research, longitudinal studies that follow individuals over decades have contributed to a growing understanding that events and conditions in childhood and adolescence shape health and lifespans in adulthood and old age, he said.

Improving the health of children and young people has profound effects later in life, argued William Dow of the Center on the Economics and Demography of Aging at the University of California, Berkeley. He pointed to new research showing that people with Medicaid insurance in childhood have better health as adults. “By reducing disability and keeping people in the labor force, Medicaid is actually paying for itself,” Dow said.

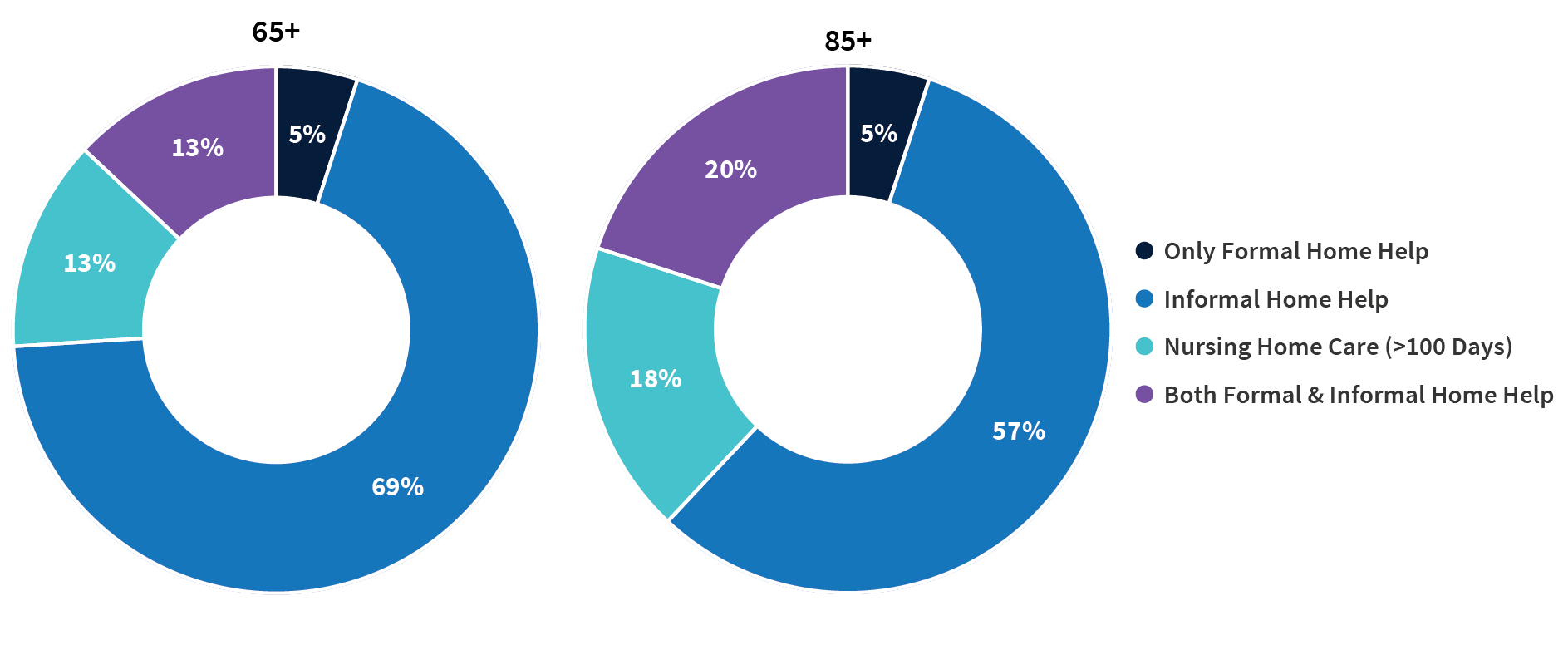

Family members provide most of the care that enables older people to live safely in their own homes, said V. Joseph Hotz of the Center for Healthy Aging Behaviors and Longitudinal Investigations at the University of Chicago. Among care recipients ages 65 and older, 69% receive only informal home care from friends and relatives, whereas just 5% receive only formal paid home care (Figure 2).

But a care gap is emerging as the baby boom generation ages. The traditional caregiver population (ages 45 to 64) is shrinking while the number of oldest-old Americans—those most likely to need care—is growing. By 2040, there are expected to be just three traditional caregivers per person ages 80 or older—down from a 6:1 ratio in 2025, according to Census Bureau projections.

But there is some good news, Hotz adds. While research finds that adult children feel less obliged to care for stepparents, new evidence suggests that an increasing share of adult children are stepping up when older parents are in need (for example, having trouble buying food). His own analysis shows that childless older people received as much help from their siblings, other relatives, and friends as their peers received from their adult children.

Source: Jonathan Gruber and Kathleen M. McGarry, “Long-term Care in the United States,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 31881, November 2023, DOI 10.3386/w31881.

Compared with their peers who have supportive families and robust social networks, socially isolated older people face a greater risk of early death, dementia, heart disease, diabetes, and a host of other conditions, explained Debra Umberson of the Center on Aging and Population Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin. “The evidence is increasingly convincing, overwhelmingly persuasive,” she said.

Inflammation, depression, hypervigilance, alcohol consumption, and the disadvantages of lower levels of education all play a role in poorer outcomes among older adults, Umberson said. Social isolation is a modifiable risk factor; the challenge is “identifying who is most at risk, why, and what can be done.”

Research suggests that “isolation begins to increase as early as adolescence and continues steadily through the life course,” she reported. Black Americans, people living in poverty, and sexual and gender minority populations tend to experience higher levels of isolation than other groups. Experiencing the death of a family member, extreme weather events (like Hurricane Katrina, which dispersed community members), pandemics (as we saw with COVID-19), incarceration, and deportation can also disrupt families and communities.

In 2024, more than half of Americans ages 65 and older (54%) were enrolled in the Medicare Advantage program, up from just 19% in 2007. The dramatic change from a fee-for-service model to a privately run managed care model has vast implication for aging Americans, said Dan Polsky of the Johns Hopkins’ Economics of Alzheimer’s Disease and Services (HEADS) Center. Medicare Advantage plans may offer efficiency and flexibility that can lower recipients’ costs and increase access to home-based care, which most Americans say they prefer, according to Polsky. But new findings by Lauren Nicholas suggest that unpaid family caregivers may be providing more end-of-life home care for people with dementia, essentially moving costs from the formal system of payment to unpaid family members, he reported.

At the same time, traditional Medicare is not without innovations: A new program is exploring ways to meet the health care needs of both people with dementia and their caregivers, Polsky noted.

In the pipeline are new disease-modifying pharmaceutical treatments for dementia, but they require an early diagnosis, which only a fraction of people receive. Should these treatments scale, it could cost the Medicare program tens of billion dollars a year, presenting an additional challenge to the already-strained Medicare budget. Implementing new early diagnosis techniques and providing cost-effective new treatments will present complicated hurdles for the health-care delivery system, Polsky suggested.

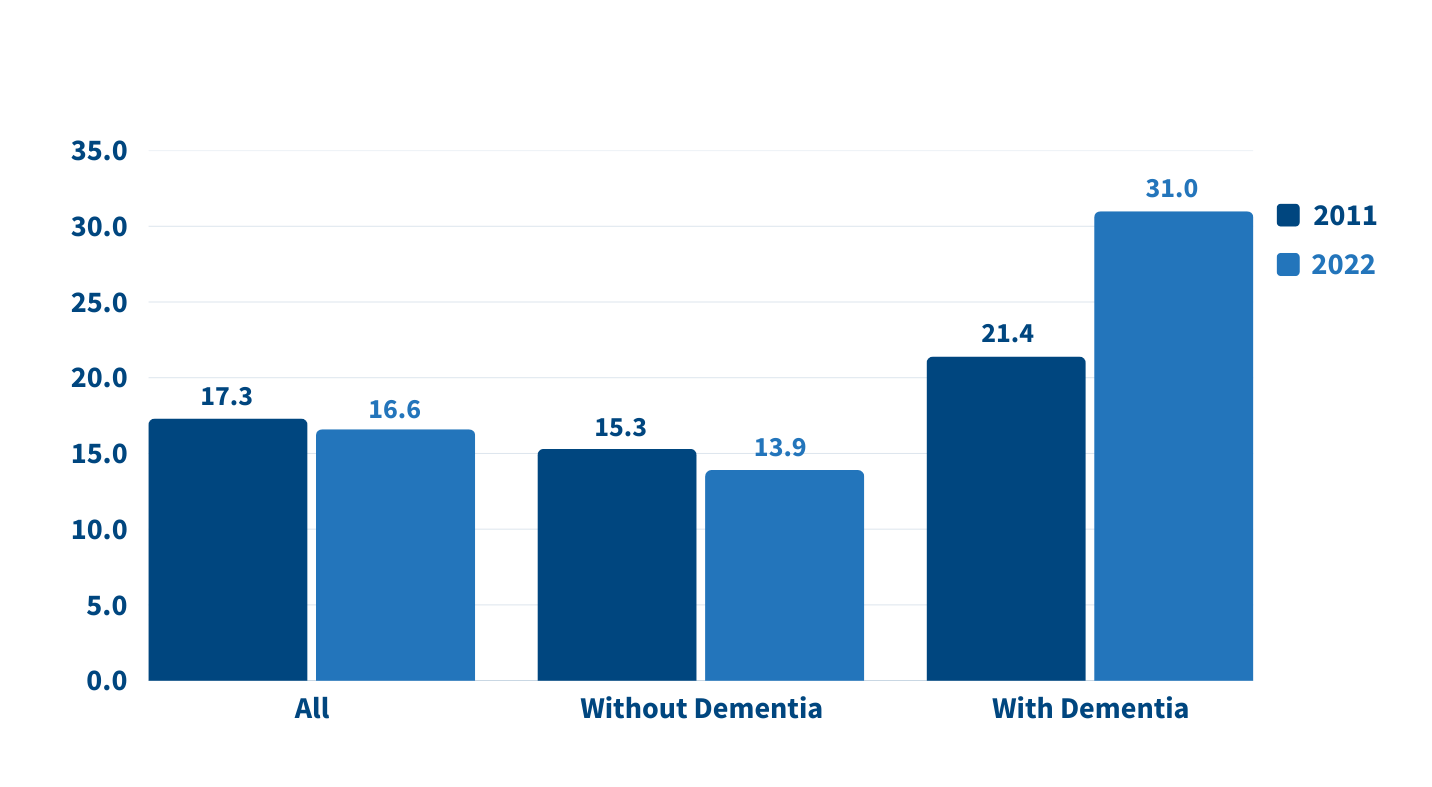

The more than 5 million family members and friends who provide unpaid care for older adults with dementia have high—and increasing—demands on their time, reported Jennifer Wolff of the HEADS Center, based on her team’s research using nationally representative data.

On average, the time that family caregivers spent helping older adults with dementia grew by almost 50% between 2011 and 2022, going from 21 hours per week to 31 hours (Figure 3). By contrast, time spent assisting older adults without dementia fell during the same period.

Wolff and team show that more than half (52%) of dementia caregivers lived with the person they were caring for in 2022, up from 39% in 2011. And the share able to hold jobs—outside their caregiving work—dropped from 43% to 35% during the same period.

Noting that the number of individuals affected by dementia is projected to triple in the next 30 years, Wolff underscored the importance of monitoring unpaid caregivers and developing interventions to support them. Some strategies could include providing direct financial assistance and tax relief, supporting flexible work arrangements and paid family leave, and using digital tools and remote monitoring technologies to help caregivers manage care more efficiently and connect with support networks.

Source: Jennifer L. Wolff, Jennifer C. Cornman, and Vicki A. Freedman, “The Number of Family Caregivers Helping Older US Adults Increased From 18 Million to 24 Million, 2011–22,” Health Affairs 44, no. 2 (2025): 189-95.

More devastating fires, storms, and hurricanes, along with greater climate variability are the “new normal,” said Elizabeth Frankenberg of the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

People who experience these events not only face an increased risk of death and disease but also lost livelihoods, diminished assets, and poor quality of life for months, years, and even decades to come, she noted.

Older people can be uniquely vulnerable due to reduced physical mobility, cognitive decline, diminished temperature regulation, and changes in economic resources, access to safety net programs, and the availability of social and family networks. Further, their ability to cope with change may be influenced by anxiety around uncertainty, a deep attachment to where they live, and difficulty making life-changing decisions.

To effectively plan for, mitigate, and adapt to severe weather events and temperature changes, demographers should team up with engineers to better understand the level of vulnerability in specific risky locations, Frankenberg said. For example, older people with lower incomes and limited mobility may need emergency support in places with rising sea levels or that are prone to wildfires.

The experts noted several promising areas for future research that can improve the health and well-being of older adults, including:

The researchers emphasized that many of these priorities require sustained investment in longitudinal data collection and interdisciplinary collaboration across aging research centers.

The scholars featured above lead many of the 15 research centers on the demography and economics of aging and Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer’s related dementias supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health for the past 30 years.

A coordinating center based at the University of Michigan supports the dissemination of findings from the centers in partnership with PRB.