Mark Mather

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

September 14, 2015

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

Contributing Senior Writer

Up to half of all premature (or early) deaths in the United States are due to behavioral and other preventable factors—including modifiable habits such as tobacco use, poor diet, and lack of exercise, according to studies reviewed in a new National Research Council and Institute of Medicine report.1

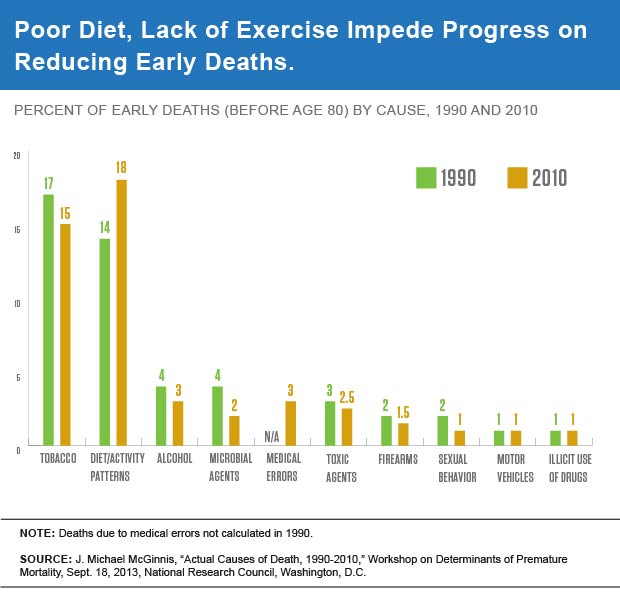

While there has been progress in reducing early deaths in the United States from certain causes, such as tobacco and alcohol use, those gains are being erased by increases in deaths linked to other factors, such as poor diet and lack of physical activity.

An analysis by J. Michael McGinnis, Institute of Medicine, showed that the percent of early deaths (defined as occurring before age 80) linked to tobacco use fell from 17 percent to 15 percent between 1990 and 2010, while early deaths attributed to poor diet and lack of exercise increased from 14 percent to 18 percent during the same period (see Figure).2 The share of premature deaths due to microbial agents, such as influenza and pneumonia, was cut in half between 1990 and 2010. There was also a decline in deaths attributed to toxic agents, such as pollutants and asbestos. Deaths due to medical errors were not calculated in 1990, but these errors accounted for 3 percent of early deaths in 2010. The drop in the share of deaths related to sexual behavior reflects a decline in HIV-related deaths.

McGinnis’ analysis showed that in 2010, nearly half of all deaths—48 percent—were linked to behavioral and other preventable causes, the same share as in 1990.

Using slightly different methods, the World Health Organization’s Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study, reported similar findings.3 Four factors—poor diet, high blood pressure, obesity, and tobacco use—were identified as primary causes of early death (defined as occurring before age 86) in the United States, according to the study led by Christopher Murray, of the University of Washington.

While deaths due to tobacco use have dropped over time, smoking remains the second leading cause of early deaths, after poor diet. Diet alone accounted for more than 650,000 early deaths in 2010—or 14 percent of early deaths overall, followed by tobacco use and obesity, at about 12 percent each. Between 1990 and 2010, obesity rose from fourth to third place among the leading causes of early death in the United States.

The GBD Study analyzed the contributions of a broad range of risk factors to early death including behaviors such as smoking, poor diet, lack of exercise, and alcohol and drug use; environmental factors such as air or water quality; and metabolic factors such as blood glucose levels or blood pressure. Many factors, such as obesity and blood pressure, are interrelated, so the GBD researchers calculated the relative risk of each factor after controlling for other related variables (see the section “Calculating Early or Premature Deaths” below for additional background on the study design).

Behavioral factors cause 35 percent of all premature deaths in the United States, according to the GBD Study, followed by metabolic risk factors (29 percent) and environmental factors (7 percent).

The results of both studies suggest that behavioral changes such as quitting smoking, improving diet, and increasing physical activity could significantly reduce the number of premature deaths in the United States. However, the report also acknowledges that “these potential risk factors will need to be examined in an integrated framework across the entire life course, taking account of the effects of differences in socioeconomic status, behavioral risk factors, and social policy.”

High levels of income inequality in the U.S. also play a role in early deaths—putting large numbers of people at risk of poor health outcomes because of their high poverty rates and low levels of social mobility.4

The United States spends more money on health care than other developed countries, but this spending does not translate into longer life expectancy. Americans live longer than they did in the past, but life expectancy in the United States continues to lag behind that of many other high-income countries. Lower life expectancy in the United States reflects, in large part, early deaths related to higher rates of tobacco use and obesity in the United States, according to recent studies by the National Research Council.5

On average, people in other high-income countries live two years longer than in the United States, according to research by Jessica Ho, Duke University.6 And, by comparison, life expectancy is increasing at a much slower rate in the United States. Ho’s calculations showed that if life expectancy in other high-income countries were frozen at current levels, the United States would not catch up to the top countries for 20 to 40 years at its current rate of increase.

Life expectancy in the United States is lowest in parts of Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta region, and in counties with large American Indian populations, according to research by Haidong Wang, University of Washington, and colleagues.7 In Kentucky and West Virginia, low life expectancy is linked to high rates of smoking. In 2010, women had the longest life expectancies in Marin County, CA (85 years) while men’s life expectancy was highest in Fairfax County, VA (82 years). Regional variations in life expectancy are linked to state and local differences in socioeconomic status, access to high-quality health care, and behavioral, environmental, and metabolic risk factors.

Pinpointing the causes of premature death can be difficult. States are responsible for compiling cause-of-death data, based on information provided by doctors, medical examiners, and coroners. In some cases, the proximate cause of death is easily identified (e.g., gun violence). But for many deaths, such as those caused by heart disease, there may be multiple contributing factors. In these cases, researchers need to assess the relative risk of death associated with particular behaviors, such as diet or exercise. For example, McGinnis estimated the number of premature deaths from different causes by applying the relative risk of death from different behavioral, environmental, and genetic factors to the population exhibiting those behaviors or characteristics.

Murray and his colleagues at the GBD Study also set “theoretical minimums” for different risk factors to assess the number of deaths that would be averted if risk factors dropped to their minimum levels. In some cases, such as smoking, the minimum is set at zero, but for other factors such as obesity, minimums are derived based on observed population characteristics.

For both calculations researchers drew on a large body of previous research linking unhealthy behaviors to poor health outcomes. Smoking increases the risk of early death from cancer, heart disease, stroke, lung diseases, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Physical activity cuts the risk of heart disease and type 2 diabetes. And poor diet—especially low fruit and vegetable intake and consuming too much saturated fat—is linked to coronary heart disease, some cancers, and diabetes.