Sara Srygley

Research Associate

The first in a series of three blogs on our forthcoming "Losing More Ground" report.

November 21, 2023

Research Associate

Watch the webinar discussing the report’s findings.

This blog is based on findings from “Losing More Ground,” PRB’s new Population Bulletin, published November 30.

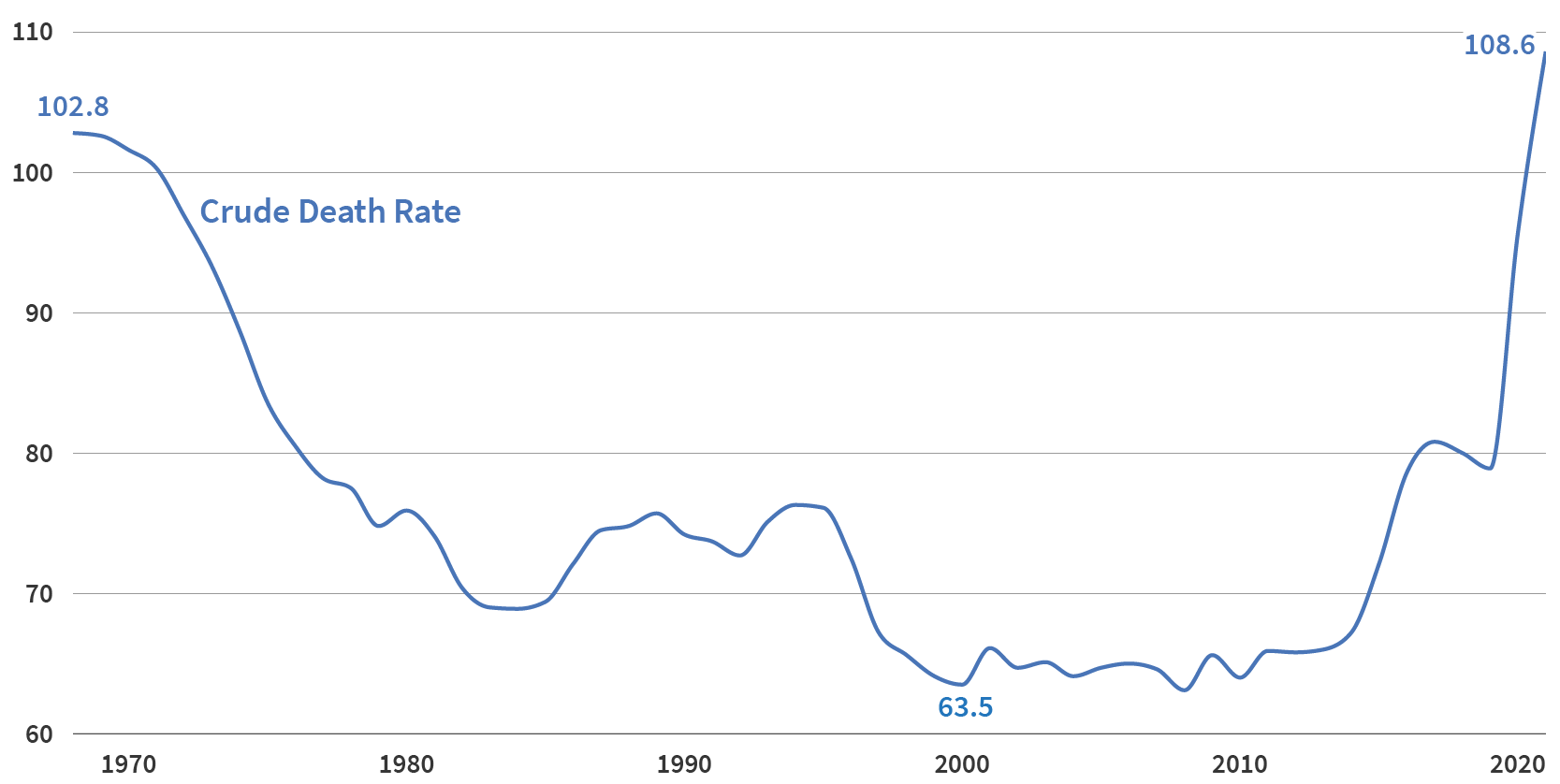

Today, a young American woman between the ages of 25 and 34 is more likely to die than she was at any other point in more than 50 years. And had the mortality rate remained flat between 2000 and 2021, nearly 40,000 young women would not have died.1

These are among the findings of PRB’s forthcoming “Losing More Ground,” an update to our 2017 report on young women’s well-being by generation, which paint a bleak picture for Millennials. Despite being more highly educated, better off financially, and less likely to have been incarcerated, Millennial young women face worsening circumstances for their health and safety compared with young women of previous generations. Maternal mortality, suicide, homicide, and accidental overdose death rates for young women have all climbed dramatically in recent years. And the risks of early death are especially pronounced for young women of color, LGBTQ women, pregnant women, and new mothers.

Source: PRB Analysis of CDC Wonder, “Underlying Cause of Death.”

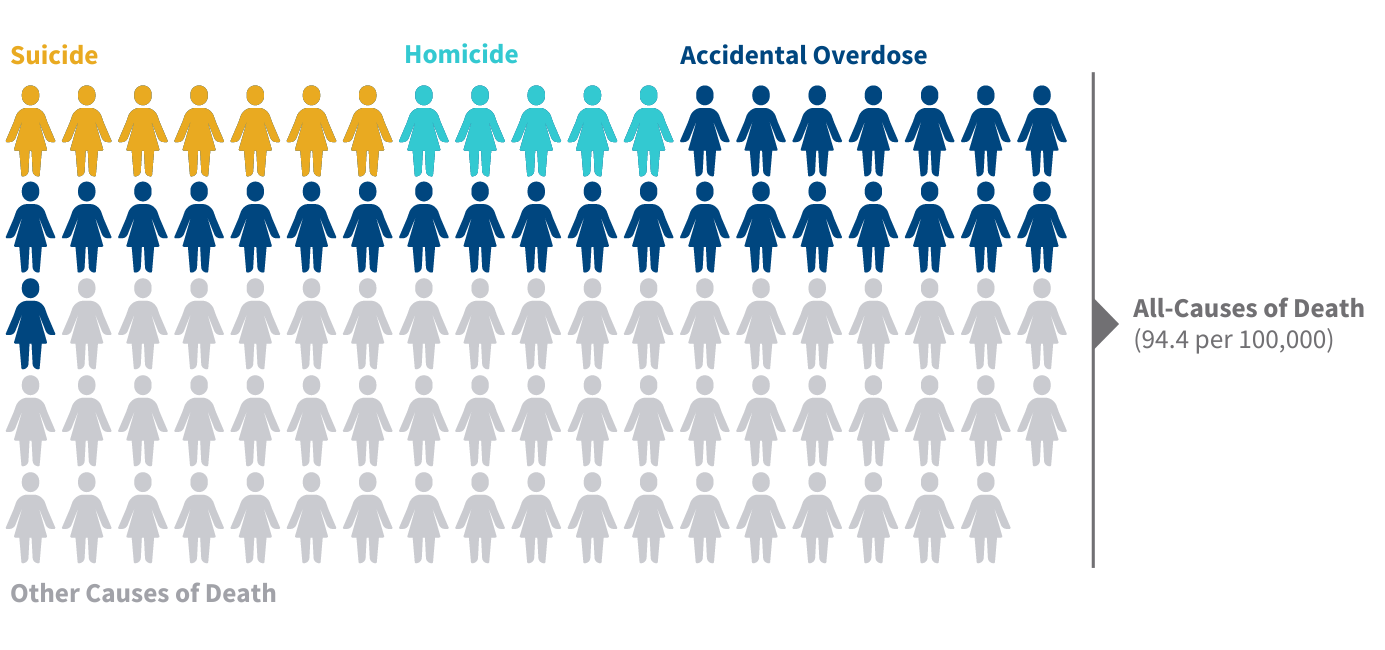

While COVID-19 has contributed to these higher death rates, the pandemic does not entirely explain this phenomenon. In fact, from 2019 to 2021—during the height of the pandemic—accidental overdose, suicide, and homicide combined accounted for 40% of the deaths of U.S. young women. The rate of accidental overdoses alone grew more than the rate of COVID-19 deaths, rising by 5.2 additional deaths per 100,000 between 2016-2018 and 2019-2021 (compared with 4.5 deaths per 100,000 due to COVID-19).

Note: Average deaths per 100,000 women 25-34 years old, 2019-2021. Icons are rounded to the nearest whole number.

Source: PRB Analysis of CDC Wonder, “Underlying Cause of Death.”

To better understand the threats to American young women today, we took a closer look at a few of the key drivers behind these troubling trends.

1. Suicide rates have increased, driven by mental health issues, pandemic effects, and more deaths among racial/ethnic minorities. Suicide rates for U.S. young women have risen steadily since the turn of the century.2 Our new report found that among women ages 25 to 34 today, the death rate from suicide is 7 per 100,000, up from a rate of 4 per 100,000 for their Gen X peers.

Women of color are particularly impacted. In fact, while white young women’s suicide rates declined by more than 6% from 2018-2021, increases among Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native young women drove an overall rise in suicide rates. American Indian/Alaskan Native young women saw a 17% increase in suicide rates from 2018-2021, with a 2021 suicide rate three times higher than that of their white peers. And although suicide rates among Black women were lower than among their white peers, Black women saw a 16% increase in suicide rates during this time.

Reported mental health issues have increased for each successive generation of young adults since at least the 1930s. And the pandemic may have exacerbated this trend, as young adults were more likely than older adults to say that the pandemic disrupted their ability to make life plans and hurt their social relationships. Social interaction is a protective factor against suicide, so by breaking connections with friends and family, the pandemic may have put more young adults at risk of self-harm.

Looking ahead, researchers have raised concern over how restrictions on reproductive health care post-Roe v. Wade may place young women at even further risk of premature death, as preliminary studies have found associations between restrictive state abortion policies and increased suicide rates.

2. Surging gun homicides and intimate partner violence are endangering young women’s lives. With recent increases in homicide deaths, our analysis in “Losing More Ground” found that Millennial women ages 25 to 34 are more likely to be homicide victims during their young adulthood than Gen X women were at the same age, and this is a recent change. Today, these young women face a homicide death rate of 4.5 per 100,000, up from 3.1 in 2013-2015. When Gen X was the same age (from 1999 to 2001), they faced a homicide rate of 4.3 per 100,000.3

More than 1 in 3 female homicide deaths in 2021 were committed by an intimate partner. While recorded domestic violence crimes were higher before the pandemic, that might have been due to a reporting issue; studies suggest that the first year of the pandemic may have brought both an increase in intimate partner violence (IPV) and a decrease in criminal reports of IPV.

High rates of gun violence have also contributed to the rising homicide rates for U.S. young women today. And the United States is an outlier among its peers. Among the six high-income nations with the highest gun-related mortality rates (including homicides, suicides, and accidental deaths), the United States sits at the top, with a rate nearly five times higher than that of and Canada, France, and Switzerland and nearly 10 times higher than that of Norway and Sweden.

3. The opioid epidemic has fueled a sharp increase in accidental deaths. Accidental deaths are the leading cause of death for U.S. young women ages 25 to 34. Accidental deaths from drug overdose among young women have increased tenfold since the turn of the century.4

The face of the opioid epidemic is increasingly female. In 2021, 27.4 young women per 100,000 died of a drug overdose, compared with just 2.7 per 100,000 in 2000.5 And while women have lower overdose death rates than men, their rate has been increasing faster than men’s since 1999.For pregnant and recently pregnant young women, the rate of increase is even more alarming: Between 2015 and 2019, accidental overdose deaths among these women increased nearly three times as much as among other women of childbearing age.6

Women are more likely to be prescribed opioid medications and may be more vulnerable to forming an addiction from less and shorter usage than their male peers, research shows. And while middle class white women are more likely to be prescribed opioids than women of color, low-income women and people of color are less likely to receive helpful medications or other treatment for substance addiction. Pregnant and parenting women may also be less likely to seek potentially lifesaving treatment for substance abuse disorders, in part for fear of legal consequences that could separate them from their children.

4. Maternal mortality rates continue to climb, pushed by structural inequality and COVID-19. The United States has a maternal mortality rate higher than that of any other wealthy nation. For young women 25- to 34-years-old, the rate rose from 19.2 deaths to 30.4 deaths per 100,000 live births between our 2017 “Losing Ground” and 2023 “Losing More Ground” reports.

While part of the increase across generations may be the result of improvements to mortality data collection and better identification of maternal deaths, these administrative changes only partially explain the recent increase.

And while the pattern of worsening maternal mortality predates COVID-19, the pandemic contributed to the increase. COVID-19 was a factor in 1 out of every 4 maternal deaths during the pandemic’s first two years. In addition, existing barriers to accessing medical care, racial inequity, and the prevalence of chronic health conditions all help explain the rising maternal mortality rate. Alarmingly, researchers estimate that the recent Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court could further contribute to rising maternal mortality rates, by as much as 20%.

Threats to the health and safety of young women in the United States have intensified with time, our analysis shows. And U.S. women are uniquely at risk compared with those in other affluent countries.7 This suggests that policies are playing an outsized role in these outcomes. Addressing the root cause of these issues would be an important step forward for the health and quality of life of young women in the United States today and in the future.

| Join our discussion of the report’s findings at our Dec. 14, 2023 webinar. |