Beth Jarosz

Senior Program Director

PRB staff offer summaries of new research and insightful sessions at the annual demography meeting.

May 13, 2024

Senior Program Director

Research Analyst

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

Contributing Senior Writer

Research Associate

Communications Manager

Census data issues, the Dobbs decision’s impact, population aging patterns, COVID-19 effects, and climate change dynamics were among the many topics discussed at the Population Association of America’s annual meeting in Columbus in April. The annual conference offered researchers and practitioners a platform to discuss new work in 235 sessions and hundreds of poster presentations.

Below, we highlight some sessions attended by PRB staff. Most of the research studies are ongoing and not yet published, so findings reported here are largely preliminary. The full conference program can be accessed here.

What do the American Community Survey (ACS), Current Population Survey (CPS), National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), and Adolescent to Adult Health Survey (Add Health) have in common? They all have declining response rates. The response rate in the NHIS fell below 50% by 2022, down from more than 80% in 1997, and even the ACS—where response is required by law—has seen a sharp drop in response rates in recent years. Data accuracy and stability are critical for disaggregating results for small population groups, measuring disparities, and looking at trends over time. But getting reliable data takes increasingly more effort. Robert Hummer, who directs the Add Health survey at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, describes himself as a “researcher, administrator, and nagger.” Part of the challenge, he says, is that there is “tremendous competition for survey attention.” But declining trust in the government, institutions, and science also plays a role. There’s no easy fix, but having an internet response option has helped by allowing survey administrators to focus more resources on the people who are least likely to respond, Hummer said.

“The great thing about the 2020 Census is that there was a 2020 Census,” according to Dan Cork, a study director at the Committee on National Statistics (CNSTAT) at the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. A panel of experts who summarized key findings in the recent CNSTAT report Assessing the 2020 Census agreed. Joseph Salvo, a fellow at the Biocomplexity Institute and Initiative at the University of Virginia, said it was a “miracle” that the Census Bureau “pulled this off.” And Gregg Robinson, formerly of the U.S. Census Bureau, said “the signature achievement of the 2020 Census was its very completion under exceptionally difficult circumstances.” What made the 2020 Census enumeration so challenging? The COVID-19 pandemic hit just as data collection was getting underway. Getting data for people living in group quarters facilities (such as prisons, nursing homes, and college dorms) was particularly difficult because many of these places were on lockdown. “Age heaping” was another problem—a result of more “proxy” responses in the 2020 enumeration; when a neighbor doesn’t know someone’s exact age, they often guess ages that end in 0 or 5. The big challenge for the 2030 Census is figuring out how to maximize self-response rates to improve data quality, panelists agreed.

The Census Bureau is revolutionizing their data infrastructure through the Demographic Frame, which includes demographic, social, and economic characteristics of individuals derived from Census Bureau surveys, administrative records, and third-party data sources. “What you’re seeing is the sleeping giant at the Census Bureau waking up,” said Salvo of the University of Virginia. Supplementing census and survey data with administrative records has been a long-term Census Bureau goal to improve data quality, reduce respondent burden, and reduce costs. However, the Demographic Frame initiative could also raise privacy concerns among data users, especially among those who distrust the government. Jennifer Ortman, a Census Bureau demographer, said transparency is key, and that the Bureau has work to do to build public support for this initiative in communities.

Since the June 2022 Dobbs decision ended the constitutional right to an abortion, states banning abortion have seen an increase in births, according to preliminary research from Daniel Dench and Mayra Pineda-Torres of the Georgia Institute of Technology and Caitlin Knowles Myers at Middlebury College. In the first half of 2023, births rose by an average of 2.3% in states with total abortion bans, equating to approximately 16,000 additional births, they reported. And bans had the greatest effect in states where they resulted in increased driving distances to abortion providers, the team added. However, prior research on the effects of abortion restrictions in Romania showed that the initial increase in births was followed by a decline, explained Jane Menken of University of Colorado, Boulder. The peak-then-dip can be explained by several factors, Menken said, which include women who are pregnant being out of the pool of people eligible to have another birth, people who are nursing being at lower risk of pregnancy, and people changing their behaviors to avoid pregnancy. Regardless of the outcome on births, Alison Norris of The Ohio State University reminded conference participants that “abortion is safe both within and outside of the formal health care system in the U.S.” and that the data show that “staying pregnant is much less safe than having an abortion.”

In the wake of the overturn of Roe v. Wade and subsequent statewide abortion bans, the average driving distance to an abortion clinic nearly doubled, found Jacob M. Souch, Drew Schaefer, and Jeralynn S. Cossman of the University of Texas at San Antonio. To access reproductive health care, residents of states with abortion bans must travel over long distances to cross state lines. Driving distance to the nearest clinic was not equal across races—Black residents in 48 counties and Hispanic residents in 45 counties had a 50% longer drive than their white counterparts. In some counties, the disparity was more pronounced; the drive was four to five times longer for Black and Hispanic patients compared to whites. In addition to rising disparities in access to reproductive health care, some clinics have experienced a steep increase in the number of patients seeking care. After 2021, 20 clinics became the closest facilities for residents in twice as many counties. (These initial findings rely on assumed closures derived from reports on state policies regarding complete bans. Coordinates used in this research were provided by ANSIRH at the University of California San Francisco.)

In 2022—faced with a historic infant formula shortage—did more new mothers decide to breastfeed? Emerging research by Marie Thoma and Lindsay Mallick at the University of Maryland and Leslie Hodges and Joanne Guthrie from the U.S. Department of Agriculture found a 5 percentage-point increase in breastfeeding initiation among new moms enrolled in WIC, the federal program that provides nutritional support (including formula) to families with low incomes. National birth certificate data were used to assess monthly breastfeeding initiation trends between 2019-2022 in 49 states (California did not report breastfeeding information). While monthly breastfeeding initiation rates were stable in 2019 and 2021, they increased significantly in the months of the formula shortage, peaking at 80.8% in June 2022. (See the team’s published findings in JAMA.)

Sexual and gender minority (SGM) older adults appear to be biologically younger than their heterosexual counterparts, reported KJ Davidson-Turner, Audrey Kelly, and Lauren Gaydosh of the University of Texas at Austin and Tara McKay of Vanderbilt University. The researchers analyzed data from the Vanderbilt University Social Networks, Aging, and Policy Study and the 2016 Health and Retirement Study, which both include biological aging measures derived from blood samples. They focused their study on older adults living in the U.S. South, an area of the country viewed as less accepting of SGM adults; they controlled for socioeconomic status.

While age at menopause mainly reflects biological and hormonal changes related to aging, psychosocial and reproductive stress might also contribute to the risk of premature and early menopause, says emerging evidence from Kriti Vikram and Sampurna Kundu of the National University of Singapore. They examine nationally representative data from the Longitudinal Aging Study in India (2017-2018), linking child marriage, early motherhood, and widowhood to premature and early menopause.

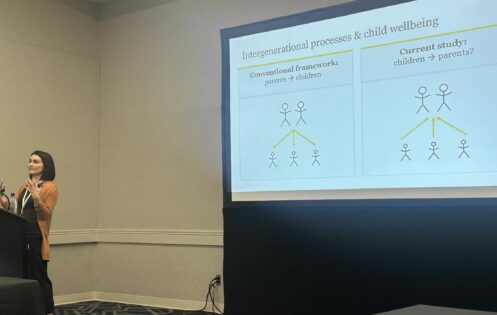

Mothers who had experienced the death of a young child were 2 to 3 times more likely to be severely depressed, found preliminary research on Malawian mothers by Emily Smith-Greenaway (University of Southern California), Abigail Weitzman (University of Texas at Austin), and Eric Lungu (Partners in Hope, Malawi). Timing also matters: More recent losses were more consequential to the mothers’ mental health, they reported. “Typically, we take a downward-effects framework, how parents affect kids. But intergenerational ties are bidirectional, and childhood adversities affect parents—things can ‘spill up,’” Smith-Greenaway said. In sub-Saharan Africa, where upwards of 50% of women of reproductive age have lost a child under age 5, “there are pernicious effects to public health, despite the fact that child mortality rates are declining,” she added. The team used 2009-2019 data on more than 1,400 mothers, nearly 14% of whom had experienced the death of a young child, from Tsogolo La Thanzi, a longitudinal study in Balaka, Malawi.

Emily Smith-Greenaway, professor of sociology and spatial sciences at the University of Southern California, presents her findings on depression among Malawian mothers who’d lost a young child.

Older adults with a disability are less likely to live with relatives in states with higher investment in home care and greater availability of nursing home beds, reported Elise Parrish of the University of Pennsylvania. In places where the long-term care infrastructure fails to meet expanding need, family members appear to be stepping in to provide care, she concluded. Her analysis is based on seven years of American Community Survey data (2012–2019), state Medicaid long-term care expenditure data, and county-level nursing home data. Results show that higher public investment and care availability are associated with decreased likelihood of living with relatives among older adults with a disability, those over 85, and those with less education. These findings suggest that family caregivers absorb care responsibilities when other options are limited, which has implications for their ability to keep their jobs and maintain their physical health, Parrish said.

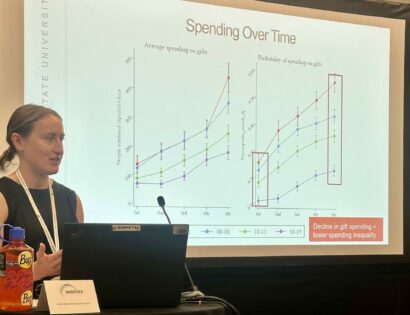

Emerging research by Mariana Amorim and Cassandra Leonard at Washington State University finds that American grandparents spend just 1.2% to 1.8% of their income on grandchildren—spending on gifts, in particular, has dropped since 1990. Though grandparents in the highest-income bracket spend several times more than those with the lowest incomes on clothing and school-related expenses, overall spending on grandchildren fell across income groups from 1990 to 2018, finds the analysis, which used data from the federal Consumer Expenditure Survey. As people live longer and have fewer children, grandparents have more opportunities to invest in their grandkids than ever before, Leonard said. “The weak social safety net and increasing economic inequality also create a growing need for support from grandparents.”

“The weak social safety net and increasing economic inequality also create a growing need for support from grandparents.” Cassandra Leonard (Washington State University) reported that American grandparents today spend just 1.2% to 1.8% of their income on their grandchildren.

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) reduces the care that unmarried daughters provide to their older parents with care needs, Anna Wiersma Strauss and Emily Wiemers of Syracuse University and Katherine Michelmore of the University of Michigan found. The EITC is one of the large U.S. anti-poverty cash transfer programs, lowering moderate- and low-income workers’ tax bills and providing an average of $3,176 to households with children; workers receive a payment if the EITC they qualify for is higher than their tax bill, they explained. Using Health and Retirement Study data, they found that every $500 increase in EITC generosity was tied to a decrease of 25 hours of care per month provided to a parent over age 65. They estimated that the monetary cost to parents of lost family care was greater than the EITC benefit. However, they found no evidence that older parents replaced that care by hiring paid care, that their EITC-eligible adult children provided financial support, or that their other non-EITC eligible children provided either care or financial support. They noted the EITC increases the incentives for paid work at the expense of family caregiving at a time the population is rapidly aging and paid care is limited and costly.

A wide body of research links health insurance coverage to better health outcomes. But older Americans dually enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid are more than twice as likely to die than those with Medicare only, finds emerging research led by Sarah Petry at the Carolina Population Center. While eligibility and benefits do not vary by state for Medicare, they do for Medicaid, available mainly to those with low incomes. Petry examined the relationship between life expectancy at age 65 and state Medicaid policy using 2000-2018 data from the Health and Retirement Study linked to a Medicaid Generosity Index developed by researchers at SUNY Albany. At age 65, life expectancy for those enrolled in Medicare was 1.4 years longer than for dual enrollees. And while Medicaid generosity was not associated with life expectancy at age 65, women and people living below the federal poverty line spent more time enrolled in both insurance programs, putting them at higher risk of death. “Medicaid policy is a critical structure, but it also critically structures how older adults experience late-life health care and needs,” she said. “What is it doing, who is it giving resources to, and why?”

You’re only as happy as your least happy kid, the popular saying goes—but are you only as healthy as your least educated? Having even one adult child without a high school diploma is linked to a higher risk of dementia for parents—and this risk is not offset by having another child with a college degree, finds emerging research by Jenjira Yahirun and Jaycob Applegate (Bowling Green State University), Krysia Mossakowski (University of Hawaii at Manoa), and Mark D. Hayward (Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin). The team examined more than 86,000 person observations from the U.S. Health and Retirement Study, equivalent to nearly 15,400 parents ages 65 and older with at least two adult children. Using event history analyses, they found that educational disadvantage—or having a child who did not complete high school—was associated with dementia onset, even if another child graduated college. “Understanding how the resources of offspring combine to influence parental health is imperative given that most older adults have more than one child,” the researchers concluded.

Between 2017 and 2022, the share of U.S. adults who were single rose by more than 5 percentage points, representing about 13.7 million more single adults in the United States, according to Michael Rosenfeld of Stanford University. And this rise was particularly noteworthy among younger adults. Difficulty forming relationships due to the unique social context of the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to the rise in singlehood, which has lingered even as vaccines became widely available, and the most restrictive pandemic policies lifted, Rosenfeld noted. Barriers to meeting new people, health concerns, variable vaccine uptake, and increasing political polarization are just a few factors that contributed to fewer adults forming relationships during the pandemic.

While a college degree is linked to lower odds of heart disease for white men, Black and Hispanic men don’t see this benefit, finds emerging research by Kelsey Shaulis at the Penn State Population Research Institute. Her study sought to examine the effect of race, gender, and education on physical and mental health outcomes among midlife adults, using 1997-2017 data from the NHIS. While Black men and women reported lower levels of psychological distress than their Hispanic and white peers, they had higher levels of heart disease, regardless of their educational attainment. These preliminary findings build on the skin-deep theory of resilience, which holds that academic success and psychological resilience for minorities can come at the cost of physical health; they also drive home the importance of looking at intersectional factors behind health outcomes, Shaulis said.

Between 2020 and 2022, the United States averaged 3,373,000 deaths annually, the most in history and 18% more than in 2019, reported Kenneth Johnson of the University of New Hampshire. In the same period, births declined by 3% to 3,645,000 annually. The net result was a 74% decline in the surplus of births over deaths—the smallest annual natural gains in a century. Between July 2021 and July 2022, more people died than were born in 75% of the nation’s counties. Because the rural population (on average) is older, sicker, and has less access to health care, COVID-19 hit rural America harder, he explained. Between July 2021 and July 2022, deaths exceeded births in 84% of nonmetropolitan counties. Many of these rural counties have long histories of deaths exceeding births that predated the pandemic, but Johnson called the recent levels of natural decrease unprecedented. Two-thirds of all nonmetropolitan counties have had more deaths than births in the last three years, he reported.

The relationship between migration patterns, climate risk, and environmental disasters is complicated by social, economic, and policy factors. Katherine Thomas of New York University highlighted the intersections of race, income, and housing tenure when exploring migration away from flood-prone census tracts in the United States. Thomas identified “immobility as vulnerability,” noting that low-income households, renters, and Black residents were least likely to relocate from neighborhoods at risk of flooding. Victoria Wang of the University of California, Los Angeles also explored patterns of migration related to climate events. Wang found that among those experiencing wildfires in California, economic advantage (in this case, higher credit score) was associated with likelihood of moving from a fire-burned neighborhood. Yet, receipt of aid was also a predictor of movement—those who received aid after experiencing a wildfire were both more likely to move away and to eventually return. Whether discussing fire or flood, these presenters highlighted that the ability to move out of neighborhoods at risk of climate disasters is not evenly shared among affected households—leaving those facing other disadvantages more vulnerable to climate-related hardships.