Diana Elliott

Senior Vice President, Programs

February 19, 2026

Senior Vice President, Programs

Senior Research Associate

Senior Fellow, McCourt School of Public Policy at Georgetown University

Public pension plans hold trillions of dollars in assets and are responsible for the current and future retirement security of millions of Americans. In recent years, though, questions have arisen about the financial sustainability of such plans.

Baby Boomers have exited the labor force in large numbers over the last decade, meaning they are now drawing payments from thousands of public pension systems across the United States. Without sufficient planning for demographic change, public pension plans will face fiscal challenges in the very near future.

In this Population Bulletin, we test different scenarios to understand how policy levers could change the population of retirees in the coming decades and affect the demand on state and local public pensions. Among our findings:

State and local governments need to address the reality that aging Baby Boomers will affect pension plans for decades to come. As we demonstrate, adjustments to retirement policies do very little to counteract the demographic pressures these plans will face. Solutions such as drawing un- and underemployed workers into the government, addressing fiscal challenges sooner rather than later, and creating flexibility in how pension plans are designed could help address these pressures. Without interventions, the failure to confront our demographic reality will lead to an increased burden for everyone.

Young children, particularly infants and toddlers, have historically been undercounted at higher rates than any other age group. A recent convening identified critical evidence gaps and outlined a research agenda designed to inform census planning and improve outcomes for children.

February 19, 2026

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

Senior Program Director

Senior Vice President, Programs

On December 17, 2025, PRB convened a small group of researchers, advocates, and policy experts to discuss factors that could impact the count of young children in the 2030 Census and the role research can play in addressing those risks. The goal was to identify shared priorities and areas where additional evidence could inform planning decisions in the years leading up to 2030.

Accurate census counts of young children matter. An undercount of young children in the decennial census means fewer resources for early childhood programs, reduced political representation for communities with young families, and flawed data for policy decisions that affect children’s health, education, and well-being. Young children, particularly infants and toddlers, have historically been undercounted at higher rates than any other age group, and the 2030 Census faces operational and budgetary constraints that could worsen this problem.

Addressing these challenges will require sustained investment in targeted research. This convening identified critical evidence gaps and outlined a research agenda designed to inform census planning and improve outcomes for children. However, translating this agenda into action depends on funders recognizing the urgency of this issue and committing resources to support timely, rigorous research in the years ahead.

This document is intended as a starting point for collaboration and a foundation for a shared research agenda focused on ensuring that young children are fully counted in the 2030 Census.

Participants agreed that the 2030 Census will be conducted under greater constraints than recent decennial censuses. Greater reliance on administrative records and online responses, combined with reduced in-person field operations, introduce new efficiencies but also new risks. These changes are unfolding alongside persistent budget uncertainty, staffing challenges within the Census Bureau, and declining trust in government.

For young children, these constraints are especially consequential. Infants and toddlers are already among the hardest populations to count because they are more likely to live in complex households, experience housing instability, and lack consistent representation in administrative data systems. Operational and contextual pressures that reduce follow-up, limit outreach, or increase reliance on imperfect data sources could compound existing challenges and exacerbate longstanding undercounts of young children.

The expanded use of administrative records was a central theme in the discussion. Participants recognized the potential for administrative data, including state birth records, to help identify young children who might otherwise be missed. But participants also emphasized that administrative records vary widely in their usefulness for census purposes.

Some administrative records lack current or usable address information, limiting their value for highly mobile families, children in informal housing, or those with complex living arrangements. Other administrative records include address data but are missing important demographic characteristics for young children, like race and ethnicity.

Participants noted that experiences with administrative records differ across programs and states. In some contexts, address coverage is relatively strong, while in others it is incomplete or unreliable. This variation underscores the need for careful, evidence-based assessment rather than assumptions about administrative record quality.

Young children in lower-income families are more likely to be missed. These families are less likely to show up in some federal records, but more likely to be included in state programs, making it important to understand which data sources best capture these children.

A central issue is whether states will be willing to share administrative data for census purposes. Concerns about privacy, potential misuse, and loss of control over sensitive information are making some states reluctant to share their data.

Taken together, uneven data quality and state participation mean that greater reliance on administrative records—without careful testing and evaluation—could amplify existing gaps, disproportionately affect the count of young children, and worsen longstanding inequities in child coverage.

Despite technological and methodological advances, an accurate address list remains the foundation of a complete census. Participants raised concerns about the future effectiveness of the Local Update of Census Addresses (LUCA) operation, which relies on state, local, and tribal governments to help identify missing or incorrect addresses, amid growing resource constraints.

When administrative records are available and of sufficient quality, they can help compensate for some address gaps—particularly for households connected to government programs. However, participants emphasized that administrative records cannot fully substitute for a complete and accurate address list. Housing instability, the growth of informal and nontraditional housing arrangements, and reduced in-field address canvassing were all identified as risks that disproportionately affect young children.

Birth certificates are another resource for improving address coverage for infants, but these data are typically held at the state level. Participants noted that state willingness to share address data may be shaped by broader trust concerns and uncertainty about how federal agencies may use or protect those data.

Trust, fear, and participation continue to shape outcomes

Participants emphasized that trust in the census and in government more broadly remains a critical determinant of participation, especially in immigrant and marginalized communities. Even proposals that are unlikely to be implemented—such as adding immigration or citizenship status questions to the census—can influence perceptions and willingness to respond.

Heightened concerns about immigration enforcement and data misuse—combined with the growing visibility of administrative data use across government— may make some parents and other caregivers more hesitant to share their information with census enumerators. Fears that data could be used for harm—or shared across agencies in ways that affect immigration status, benefits, or surveillance—were seen as a growing barrier to full participation.

While differential privacy does not affect whether children are counted, participants highlighted its implications for how census data are used. Noise added to protect confidentiality can distort small-area counts of young children and other population subgroups, making it harder to identify local undercounts, evaluate interventions, and allocate resources. Participants agreed that research is needed to help data users interpret and responsibly apply these data for child-focused policy and funding decisions.

Across topics, participants identified a gap between descriptive knowledge and actionable evidence. While much is known about which children are missed and where undercounts occur, there is far less evidence explaining why omissions happen or which interventions are effective.

Specific gaps highlighted during the discussion included:

Participants emphasized that without addressing these gaps, the field risks repeating past analyses without changing outcomes.

Participants noted that research on the undercount of young children has often depended on the efforts of individual Census Bureau staff or small teams, rather than being embedded as a sustained, agency-wide research priority. As a result, testing and evaluation related to young children has been uneven and vulnerable to shifting operational demands.

Based on the discussion, participants coalesced around a research strategy guided by three principles:

Participants identified the need for research that goes beyond demographic correlates to examine the mechanisms driving child omissions. This includes qualitative and mixed-methods studies exploring why some parents and caregivers aren’t reporting young children in the census, how household dynamics affect reporting, and how privacy and trust concerns shape responses.

Given the central role administrative records are expected to play in 2030, participants called for rigorous assessment of these data sources for young children. Priority areas include understanding gaps in coverage for infants and young children, exploring state-level differences in administrative data accuracy and program participation, and modeling the effects of reduced data sharing.

Simulation and scenario analyses were highlighted as especially useful because they allow researchers to test “what-if” scenarios—such as reduced field capacity or uneven access to administrative data—and assess how those conditions might affect the count of young children.

Research is needed to assess risks to address coverage, including the effectiveness of LUCA participation under constrained budgets and the impact of growing housing instability on census coverage for children.

Participants emphasized the need for updated research on trust, fear, and willingness to participate in the census. This research should account for the broader policy and enforcement environment, the increasing visibility of administrative data use, and the need to identify strategies that can reduce fear and rebuild trust among parents and other caregivers.

A consistent theme was the need to move from documenting problems to testing solutions. Participants emphasized a staged approach that identifies promising interventions, tests them using available data or experimental designs where possible, and translates findings into actionable guidance.

Finally, participants stressed that research must be communicated in ways that resonate with policymakers, funders, and community leaders. Linking census accuracy for young children to funding, services, and long-term outcomes was seen as essential for sustaining attention and investment.

Several participants emphasized that improving the Census Bureau’s population estimates of children—both within and outside the decennial census—could have benefits well beyond 2030. Stronger child population estimates would improve the Bureau’s ability to target census operations, assess coverage through demographic analysis, and support federal funding formulas and survey controls throughout the decade. Participants noted that these improvements would remain critical even if the 2030 Census faces significant challenges, given the widespread reliance on population estimates across federal programs.

The December convening underscored both the urgency and the opportunity facing the research community. Without targeted, coordinated research, longstanding challenges in counting young children are likely to persist into 2030. At the same time, the period leading up to the next census offers a window of opportunity to generate evidence that can shape decisions and improve outcomes.

The research community cannot do this work alone. Funders have a critical role to play in supporting the timely, rigorous research needed to improve child coverage in 2030. Strategic investments now—in qualitative studies, administrative data evaluation, and intervention testing—can yield measurable improvements in how young children are counted and, ultimately, in the resources and services that reach them. The window for impact is closing, and sustained funding commitment is essential to translate this research agenda into meaningful change.

Funding for this work was provided by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation.

January 22, 2026

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

Senior Research Associate

Senior Policy Analyst, UnidosUS

In the U.S., four out of five Latino adults—38.5 million people—are part of the working class, powering essential industries like construction, agriculture, and hospitality.

In a new research series, PRB and UnidosUS are exploring the characteristics of this group, offering insights to inform policies that expand economic opportunity. The inaugural report looks at the demographic profile of working-class Latinos, including age, race, gender, generational status, and education level, as well as differences across states.

October 21, 2025

Senior Technical Director

Senior Program Director

Over the past five decades, the global average fertility rate has fallen from about 4 children per woman to 2.2 today. Two-thirds of the world’s population now lives in countries where the total fertility rate is below the replacement level of 2.1 (see Figure 1). This includes almost all high-income countries and much of Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Fertility remains highest in sub-Saharan Africa, parts of South Asia, and some Pacific islands, though rates are gradually declining.

Even as global fertility converges downward, significant variation remains (see Figure 2). In Africa, fertility is still 4.1 children per woman, but with wide variation across countries, from 1.2 (Mauritius) to 6.0 (Chad). Even regions with low average fertility, like Asia and the Americas, have large differences within and across countries.

As fertility falls, populations age, creating new social and economic pressures. This guide explains what’s behind falling fertility rates, unpacks common assumptions about fertility decline, and explores how policymakers can respond. It aims to spark informed, data-driven dialogue and reporting that shifts the focus from fear to facts and from panic to practical solutions that support societies to adapt and thrive.

Fact: To understand fertility, demographers look at three factors: preferences (the number of children people would ideally like to have), intentions (the number of children people realistically plan for, given their circumstances), and behaviors (the actual number of children people end up having). Even in low fertility countries, most people still want children—but preferences often exceed intentions, and intentions often exceed actual births.

Childbearing is reduced both by shifting priorities (valuing careers, leisure, and personal fulfillment over marriage and larger families) and by constraints such as high costs, work-family conflict, unequal gender roles, economic insecurity, delays in partnering, and changing cultural norms.

Unknown: What factors, if any, can narrow gaps across fertility preferences, intentions, and behaviors. These factors can help explain how people plan for families, but there are some limitations. This information is collected through surveys, which are subject to bias; for instance, we know that societal expectations can lead some people to report wanting children, even if they’re unsure or don’t plan to. Additionally, survey results provide a snapshot in time, but preferences and intentions about children can and do shift. For example, younger people often plan for more children but adjust their intentions as life circumstances change. This can contribute to confusion about how individual choices are connected to fertility rates.

Fact: Comprehensive global reviews find no strong evidence that infertility is increasing, so it cannot explain the widespread decline in fertility rates. Measuring infertility is challenging, as definitions and data vary across countries.

Worldwide, about one in six people experience infertility—not becoming pregnant after 12 months of unprotected sex—at some point in their lives. Rising childlessness is mostly shaped by social and economic factors, described above. Still, some trends, like having children later, can influence both infertility and fertility decline since delaying pregnancy shortens the reproductive window and biological ability to have a baby reduces as maternal age increases.

Unknown: Reliable infertility data are still limited in many countries, making it difficult to track trends or separate true biological infertility from voluntary delays and decisions to have fewer children. It also remains unclear how much lifestyle and environmental factors—such as stress, pollution, or obesity—might contribute to infertility trends.

Fact: Cash incentives and tax breaks given to parents tend to create only modest, short-term increases in births, often encouraging people to have children sooner, but with limited impact on overall births.

While such benefits can ease the financial burden of raising children in the short term, they typically make up only a small share of household income. It is possible that larger, long-term incentives could yield more births, but raising fertility to replacement levels this way would likely be prohibitively expensive.

Unknown: If financial incentives would have a stronger effect if paired with generous family support policies (see below).

Fact: Designed to make it easier for couples to work and raise children, these policies have only modest effects on fertility, often encouraging parents to have additional children but not people without children to enter parenthood.

However, such programs remain important for their other benefits, including reducing stress, improving well-being, and giving parents more options.

Unknown: Whether scaling up to universal, generous family supports could help close the gap between intended and actual births, or whether cultural and economic drivers will keep fertility low regardless. We also don’t know whether implementing such policies before the fertility rate declines below replacement level could help countries prevent or delay the decline to very low fertility; most countries with generous family supports only brought them on after fertility had already dropped.

Fact: Restrictive policies do not sustain higher fertility and come with serious health and human rights costs. Romania’s abortion ban in 1966 briefly doubled births, but fertility soon fell again while unsafe abortions, maternal deaths, and numbers of abandoned children soared.

Similarly, in the immediate aftermath of the 2022 Dobbs decision that overturned federal abortion protections in the U.S., states that enacted abortion bans saw a modest increase in births compared to projected trends (about 2–3% more than expected). However, total births continued to fall in most of states with bans, suggesting a temporarily slowing rather than a reversal. Limiting reproductive rights undermines health and freedom without addressing the real reasons families have fewer children.

Unknown: How far governments concerned about low fertility may go to restrict reproductive rights, and how such actions might backfire socially and politically.

Fact: Among high-income countries, those with lower gender equality (such as South Korea and Japan) tend to have lower fertility rates, while in those with higher gender equality—where caregiving and paid work are more equally shared—fertility tends to be somewhat higher.

Still, this pattern isn’t simple: We don’t know whether this relationship is causal, and some highly gender-equal countries (such as Norway and Sweden) also have very low fertility. In low-income countries with very high fertility, evidence does suggest that greater gender equality has contributed to fertility decline.

Unknown: Whether cultural norms will shift toward more equal sharing of work and caregiving, how meaningful those shifts might be, and whether they will raise fertility or primarily improve well-being (while fertility remains low).

Fact: Immigration can ease labor shortages and slow aging in the short to medium term. But immigration is rare (just 3-4% of the global population has migrated internationally) and as fertility falls worldwide, the global pool of young migrants will shrink, limiting immigration’s potential as a long-term solution.

Unknown: How much or where migration will actually flow in the future, and whether political and social systems will allow enough immigration to meaningfully ease pressures from aging.

Fact: Fertility decline leads to population aging—or, a growing share of older adults relative to younger people. At the family level, fewer children share the responsibility of supporting aging parents and grandparents, straining household finances. At the societal level, a shrinking pool of workers to retirees strains pension and health care systems and can slow economic growth. Population aging does strain retirement systems and shrink the workforce, but there is a lot societies can do to adapt.

Countries can experiment with a range of solutions such as adopting pension reform, raising the retirement age, getting more people into paid work, prioritizing immigration, and investing in productivity and innovation.

Unknown Whether these adaptations will be enough—since no society has ever faced aging on this scale and the pace of aging is rapid in low- and middle-income countries new to the trend.

Want to learn more about global fertility decline? Here we break down the key forces shaping global fertility patterns and what these shifts mean for families and societies, unpacking the demographic trends behind the assumptions discussed above.

Global fertility decline has been driven by lower child mortality, wider access to family planning, more education and jobs for women, and urbanization. The more recent decline to below-replacement and very low fertility levels reflects both economic challenges and broader social and cultural changes.

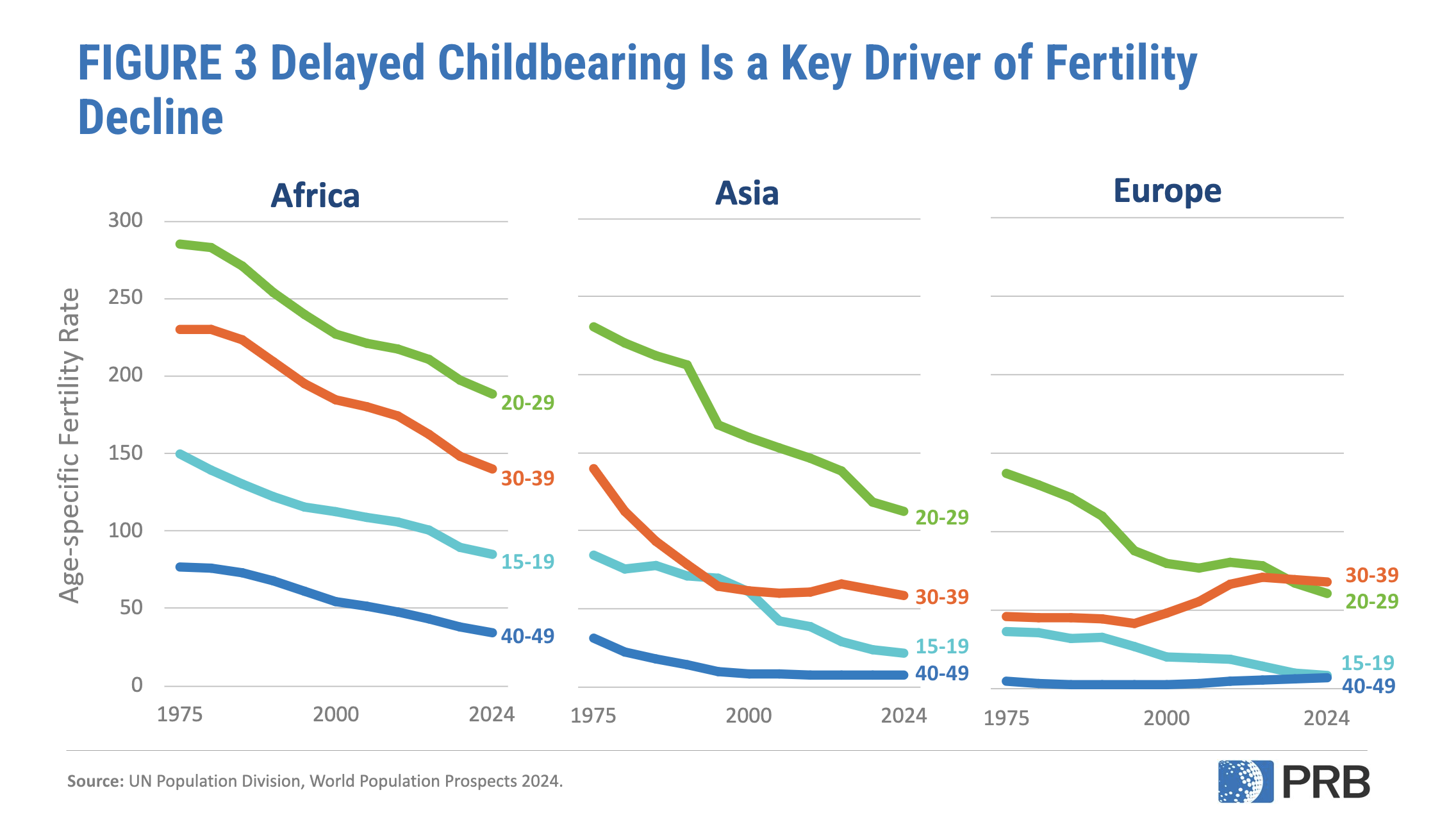

Rising costs, unstable jobs, delayed partnerships, and inflexible work environments make it harder to raise children, while greater emphasis on education, careers, and personal freedom has redefined ideas about family and what living a fulfilling life looks like (Figure 3). These factors explain why fertility is below replacement even where people still want children.

The total fertility rate is the average number of children a woman is expected to have over her lifetime if age-specific fertility trends prevail. It is a hypothetical measure based on current birth rate (importantly, it does not represent or predict the actual number of children women have). The replacement level fertility rate is the average number of children a woman needs to have for a population to replace itself from one generation to the next, assuming no migration and a natural sex ratio at birth (slightly more boys born than girls ). It is typically about 2.1 children per woman—two parents “replace” themselves with two children, plus an extra margin above zero because not all children survive to adulthood. However, even when fertility falls below 2.1 children per woman, population can continue to grow for several decades. That’s because many people are still in their childbearing years, so births remain high for decades, a pattern called population momentum.

The 2.1 figure can be a helpful benchmark for gauging whether populations might grow or shrink over time, even though actual replacement levels vary. But treating 2.1 as a “magic number” for stability is misleading: it ignores mortality and migration trends and says nothing about population momentum or population composition, such as age structure. Using 2.1 as a target fertility rate can also exacerbate fear about population decline and lead to policy solutions that focus only on raising birth rates. Such approaches can undermine reproductive rights, gender equality, and family well-being, while distracting from the rights-based priority of ensuring that people can have the number of children they want.

Population aging itself reflects progress: people living longer, healthier lives and women having more options and opportunities. Older adults are important contributors to societal and economic well-being, strengthening families and communities through caregiving, financial support, and volunteering. Many also remain in the labor force and could contribute even more with supportive policies. As societies adapt, population aging can also spur technological innovation, particularly in health care, assistive technologies, and automation, and even fuel a “silver economy” for goods and services for older adults. It also invites new thinking on gender roles, work-life balance, and more gender-equitable caregiving policies for both children and older adults.

Policymakers should focus first on helping women and families achieve the number of children they want. That means reducing the barriers between fertility preferences, intentions, and behaviors by investing in proven supports: affordable childcare, paid parental leave, flexible work arrangements, affordable housing, and gender equality in caregiving. These policies may not reverse fertility to “replacement level,” but they expand choices, improve well-being, and may close the gap between ideals and realities.

At the same time, evidence shows fertility is unlikely to return to past levels. Even if a country were to experience an unprecedented fertility rebound, it would take many decades to see the workforce or population grow again. Thus, societies must actively adapt rather than try to restore the past. Preparing for aging means strengthening pension and health systems, extending healthy working lives, investing in innovation and productivity, and expanding labor markets to engage groups typically underrepresented in paid work, including women, people with disabilities, older adults, and immigrants. Population aging is inevitable, but with adaptation, societal decline is not.

Too often, discussions about fertility decline center on the same tired question—“How do we get women to have more children?”—and end up with the same predictable answers. But there’s a much richer story to tell.

Around the world, new and overlooked ideas are emerging that can help families of all kinds thrive and help societies adapt to demographic change. Fresh angles to explore might include:

If you’re reporting on these issues, reach out—we’re here to help with data, context, and story ideas. To schedule an interview, please contact media@prb.org.

Families face the financial burden of paying out-of-pocket for care not covered by Medicare and Medicaid and the emotional toll of day-to-day caregiving.

Today, an estimated 7.2 million Americans ages 65 and older live with dementia. While conversations around dementia often evoke nursing homes, most older Americans living with dementia are actually aging in place in their homes. Home-based care has become more common over the last decade, partly because it is more affordable and aligns with what many people prefer.

People living with dementia often face both medical and practical barriers to obtaining care, including challenges with memory, decision-making, and mobility. These difficulties make access to effective care at home not just helpful but essential to supporting their ability to remain safely in the community.

Despite its benefits, home-based care is not without challenges, including the financial burden of paying out-of-pocket for services not covered by Medicare and Medicaid and the emotional toll on family members who often take on day-to-day caregiving responsibilities. Understanding how home-based care works for the growing population of older adults with dementia is critical for improving how dementia is managed in the community and providing better support for older adults and their families.

Home-based care typically falls into two categories: home health care and home care. Home health care refers to medical services provided by licensed professionals, including skilled nursing care, physical therapy, and medical social services. It is covered by Medicare if prescribed by a doctor or nurse practitioner. Home care refers to non-medical services to assist with housekeeping and the activities of daily living, such as bathing and dressing. Medicare does not cover home care unless it is provided with medical care, but Medicaid covers home care in some states.

Based on data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) and Medicare claims between 2012 and 2018, Julia Burgdorf and her colleagues found that approximately 30% of home health care users had a dementia diagnosis.1 Older adults with dementia were twice as likely to use home health care compared to those without dementia.

About half of those with dementia were referred to home health care without a preceding hospitalization, compared to slightly less than a third of those without dementia. This finding highlights the importance of home health care as a key source of clinical care for older adults with dementia, not just for recovery care, Burgdorf and her colleagues said.

Once enrolled in home health care, people with dementia received care more times (an average of 1.4 times compared to 1 time) and for longer periods (median of 56 versus 40 days) than people without dementia. They were also more likely to receive personal care, medical social work, and speech-language pathology services than those without dementia.

However, among people who received services, those with dementia had fewer visits for skilled nursing and physical therapy, the researchers found.

“Existing prospective payment structures incentivize HHC providers to limit the number of visits in order to lower costs and maximize profits,” they wrote. And “the 2020 implementation of a new Medicare HHC payment model, the Patient-Driven Groupings Model (PDGM), may further incentivize limiting visits for people living with dementia.”

The new payment model aims to reimburse providers based on how sick patients are—but it doesn’t directly account for dementia status, Burgdorf and team note. It also reduces reimbursement for community referrals, though many people with dementia enter care this way. Differences in coverage between Medicare Advantage (private plans) and fee-for-service (the traditional government-run plan), along with workforce shortages and fragmented care systems, may create additional barriers for people with dementia, they explain.

Burgdorf and colleagues suggest several ways to improve home health care for people with dementia, including:

Many older adults end up paying for home care out of pocket because long-term care is not included in Medicare, Medicaid coverage is inconsistent across states, and few people have private long-term care insurance, according to another analysis.

“The financial burden of out-of-pocket payment for home care is significant, particularly among people with dementia and those with limited income and wealth,” conclude Karen Shen and colleagues, who used Health and Retirement Study (HRS) data (2002-2018) to measure the financial burden of home care.

Home care also often results in ongoing expenses over a long period of time, unlike most other health care costs, they found.

In recent years, people with dementia made up one-third of an estimated 3 million people who received home care and almost half (45%) of the over 600,000 people who paid for at least some of this care out of pocket, according to the researchers.2 Among those with dementia who paid out-of-pocket, half (51%) spent over $1,000 per month, compared to one-fourth (26%) of those without dementia. Additionally, people with dementia were much more likely to pay for full-time help, defined as 40 hours or more per week, compared to those without dementia (46% versus 22%).

Although higher-income individuals are more likely to pay out-of-pocket, many people with lower incomes also do so, largely because those with fewer financial resources are disproportionately affected by disability and dementia, the authors note. In fact, about half of those paying for home care out of pocket were poor or near-poor, defying the common perception that private home care is used only by individuals with higher incomes.

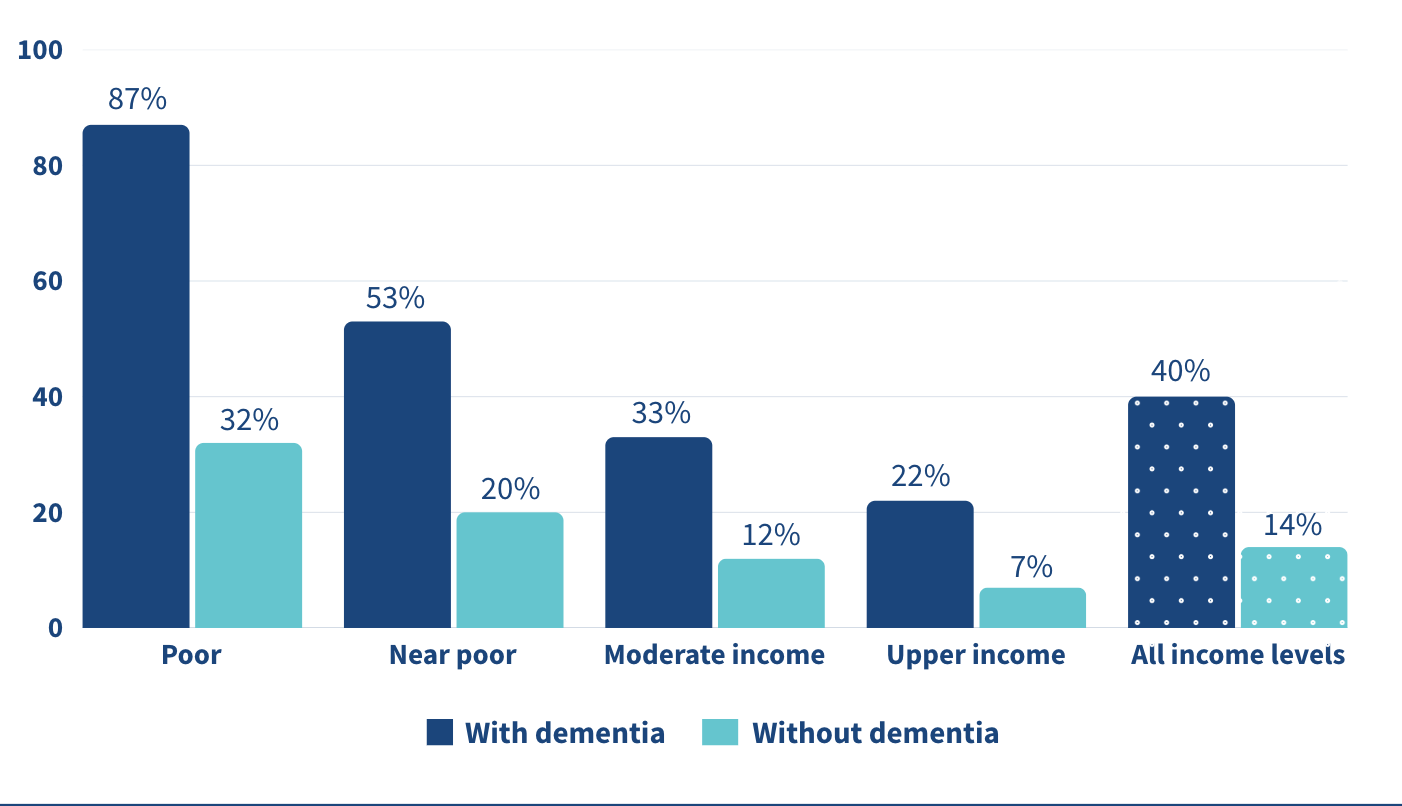

Those who are poor and have dementia experienced disproportionate financial burdens, as they spent 87% of their household income on home care, compared to 32% spent by their peers without dementia, and 22% spent by high-income individuals with dementia (See figure).

These findings suggest that those with dementia and limited financial resources may not be getting the care they need.

“Policies aimed at easing the financial burden of home care are essential, particularly for low-income individuals with dementia who experience the greatest financial burden,” argue Shen and her colleagues.

They recommend policies to reduce unmet care needs and financial hardship while also making the system more equitable and responsive to the realities of aging at home with dementia, including:

To make these programs financially sustainable, they recommend targeting benefits to the most vulnerable individuals and incorporating cost-sharing mechanisms so that those with more resources help shoulder the cost of care.

Note: “Poor”: 100% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL); “Near-poor”: 100-200% of FPL; “Moderate-income”: 200-400% of FPL; and “Upper-income”: >400% of FPL.

Source: Karen Shen et al., “Paying for Home Care Out-of-Pocket Is Common and Costly Across the Income Spectrum Among Older Adults,” Health Affairs Scholar 3, no. 1 (2025).

Even with paid home care, most dementia care still falls on family and friends. In the United States, over 11 million unpaid caregivers provide over 15 billion hours of dementia care every year, according to Yeunkyung Kim and his colleagues.3 One way to give caregivers a break is through respite care—short-term care that lets family members step away for a few hours or days. Ultimately, respite care aims to help sustain caregiver health and delay the institutionalization of the people in their care.

Yet its use remains limited. Only 16% of Black caregivers used respite services compared to 32% of white caregivers in 2015, representing a significant gap of 12 percentage points, Kim and team found. Although this racial gap had been reduced or eliminated by 2017, respite care use remained low among both Black and white caregivers. Data are from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) and the National Study of Caregiving (NSOC) from 2015, 2017, and 2021.

Even though there have been efforts to expand access, too many caregivers are still doing this difficult work without enough support. This highlights the persistence of structural and informational barriers to care—including financial cost, lack of awareness, cultural expectations, and insufficient supply of respite providers.

The underuse of respite care represents a missed opportunity to support the mental and physical health of caregivers, and thereby also the stability of dementia care at home.

Kim and colleagues recommend several strategies to improve access to respite care for families supporting older adults with dementia, including integrating respite services more fully into long-term care systems, particularly through expanded support in Medicaid-funded programs like home- and community-based services waivers.

Better outreach and clearer communication could also raise awareness of available services, since many caregivers remain uninformed or face fragmented information, the researchers note. There is a clear need for more flexible respite options that can accommodate the diverse cultural, financial, and scheduling needs of caregivers. For example, offering evening or weekend respite hours for those who work during the day, or providing in-home options for caregivers who are uncomfortable with facility-based care, could make a meaningful difference.

Simplifying program design, reducing waitlists, and ensuring consistent availability are also key to increasing use of these services, they said.

1. Julia G. Burgdorf et al., “Variation in Home Healthcare Use by Dementia Status Among a National Cohort of Older Adults,” The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 79, no. 3 (2024).

2. Karen Shen et al., “Paying for Home Care Out-of-Pocket Is Common and Costly Across the Income Spectrum Among Older Adults,” Health Affairs Scholar 3, no. 1 (2025).

3. Yeunkyung Kim et al., “Trend in Respite Use by Race Among Caregivers for People Living With Dementia,” The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 79, Supplement 1 (2024): S42-S49

Experts point to key dynamics challenging policymakers, health care planners, and families

August 6, 2025

Contributing Senior Writer

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

Early onset chronic disease, a growing caregiving gap, and climate change are among the major trends affecting the health and well-being of older Americans and their families, according to leading scholars from across the country.

Before a standing-room-only crowd at the 2025 meeting of the Population Association of America in Washington, D.C., experts identified seven key themes that are challenging policymakers, planners, and families as the U.S. population rapidly ages.

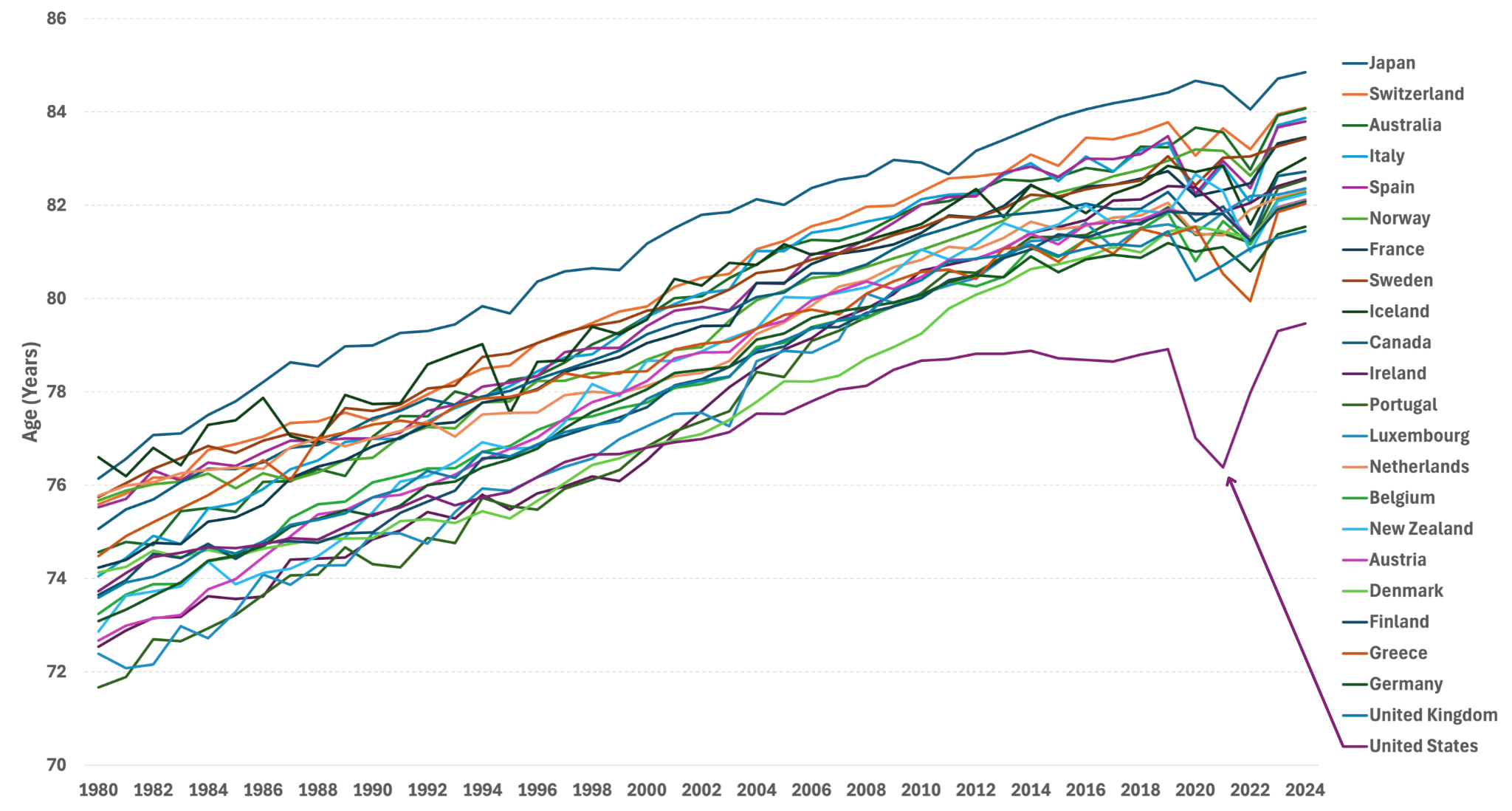

The United States has experienced the earliest and greatest slowdown in life expectancy improvements among higher-income countries, reported Eileen Crimmins of the University of Southern California/University of California-Los Angeles Center on Biodemography and Population Health.

“We have horrible life expectancy—and it’s getting worse and worse,” she said, pointing to the diverging line for the United States in Figure 1. Though premature deaths from heart disease and stroke have declined, Americans today are unhealthy for a longer portion of their lives, coping with chronic diseases and conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, cancer, and heart problems.

While we “have a long way to go” to improve the health of the U.S. population, Crimmins said, new research into biomarkers gathered through blood and other medical tests is offering clues into what speeds up or slows down the aging process, including stress levels, income, and social connections over a lifetime.

Source: United Nations, World Population Prospects.

While advances in health care have succeeded in preventing many early deaths, older people are spending more time living with chronic diseases today than two decades ago, Crimmins’ forthcoming research shows. Americans spent more years after age 65 living with diabetes, cancer, heart disease, arthritis, and high blood pressure in 2018 than in 1998, she has found.

Scott Lynch of the Duke Center for Population Health and Aging agrees. Over the past century, complex chronic conditions like cardiovascular disease and cancer have replaced infectious diseases like pneumonia and tuberculosis as the leading causes of death, he noted. In addition to biomarker research, longitudinal studies that follow individuals over decades have contributed to a growing understanding that events and conditions in childhood and adolescence shape health and lifespans in adulthood and old age, he said.

Improving the health of children and young people has profound effects later in life, argued William Dow of the Center on the Economics and Demography of Aging at the University of California, Berkeley. He pointed to new research showing that people with Medicaid insurance in childhood have better health as adults. “By reducing disability and keeping people in the labor force, Medicaid is actually paying for itself,” Dow said.

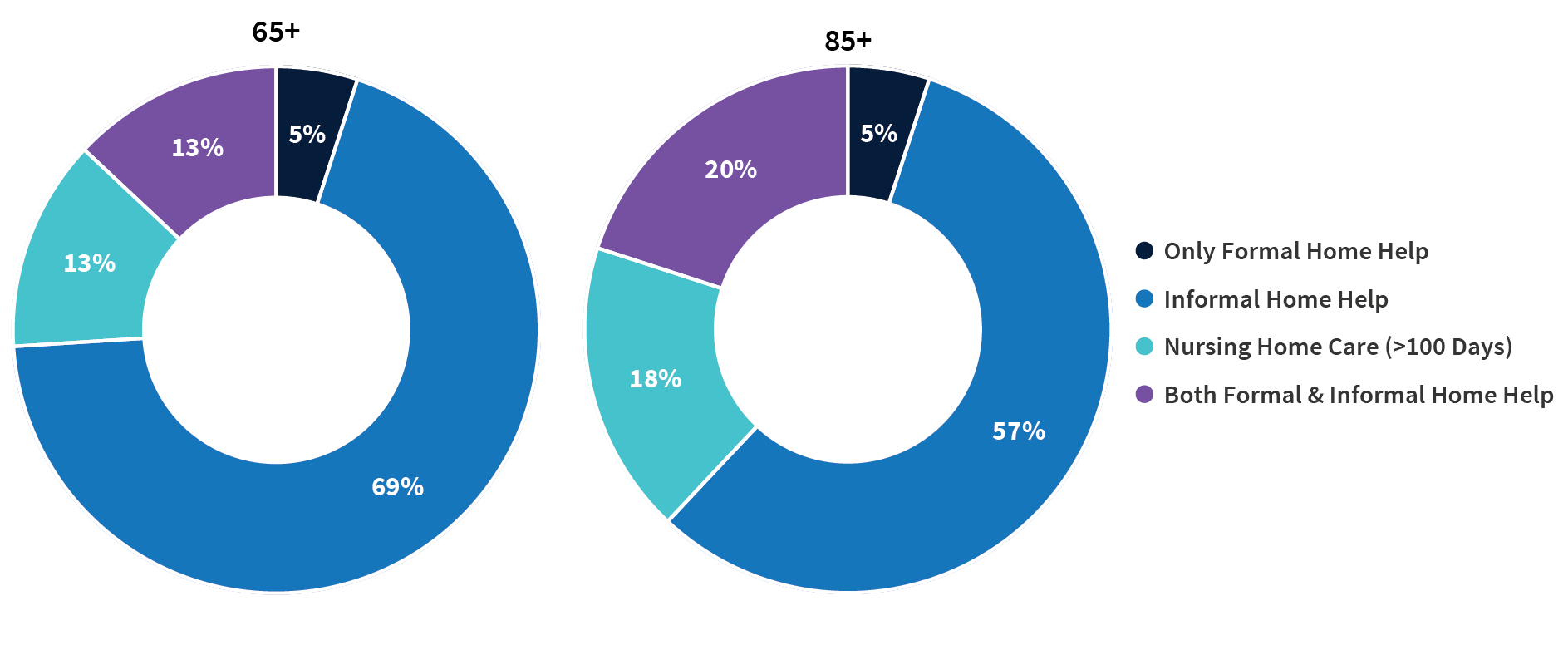

Family members provide most of the care that enables older people to live safely in their own homes, said V. Joseph Hotz of the Center for Healthy Aging Behaviors and Longitudinal Investigations at the University of Chicago. Among care recipients ages 65 and older, 69% receive only informal home care from friends and relatives, whereas just 5% receive only formal paid home care (Figure 2).

But a care gap is emerging as the baby boom generation ages. The traditional caregiver population (ages 45 to 64) is shrinking while the number of oldest-old Americans—those most likely to need care—is growing. By 2040, there are expected to be just three traditional caregivers per person ages 80 or older—down from a 6:1 ratio in 2025, according to Census Bureau projections.

But there is some good news, Hotz adds. While research finds that adult children feel less obliged to care for stepparents, new evidence suggests that an increasing share of adult children are stepping up when older parents are in need (for example, having trouble buying food). His own analysis shows that childless older people received as much help from their siblings, other relatives, and friends as their peers received from their adult children.

Source: Jonathan Gruber and Kathleen M. McGarry, “Long-term Care in the United States,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 31881, November 2023, DOI 10.3386/w31881.

Compared with their peers who have supportive families and robust social networks, socially isolated older people face a greater risk of early death, dementia, heart disease, diabetes, and a host of other conditions, explained Debra Umberson of the Center on Aging and Population Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin. “The evidence is increasingly convincing, overwhelmingly persuasive,” she said.

Inflammation, depression, hypervigilance, alcohol consumption, and the disadvantages of lower levels of education all play a role in poorer outcomes among older adults, Umberson said. Social isolation is a modifiable risk factor; the challenge is “identifying who is most at risk, why, and what can be done.”

Research suggests that “isolation begins to increase as early as adolescence and continues steadily through the life course,” she reported. Black Americans, people living in poverty, and sexual and gender minority populations tend to experience higher levels of isolation than other groups. Experiencing the death of a family member, extreme weather events (like Hurricane Katrina, which dispersed community members), pandemics (as we saw with COVID-19), incarceration, and deportation can also disrupt families and communities.

In 2024, more than half of Americans ages 65 and older (54%) were enrolled in the Medicare Advantage program, up from just 19% in 2007. The dramatic change from a fee-for-service model to a privately run managed care model has vast implication for aging Americans, said Dan Polsky of the Johns Hopkins’ Economics of Alzheimer’s Disease and Services (HEADS) Center. Medicare Advantage plans may offer efficiency and flexibility that can lower recipients’ costs and increase access to home-based care, which most Americans say they prefer, according to Polsky. But new findings by Lauren Nicholas suggest that unpaid family caregivers may be providing more end-of-life home care for people with dementia, essentially moving costs from the formal system of payment to unpaid family members, he reported.

At the same time, traditional Medicare is not without innovations: A new program is exploring ways to meet the health care needs of both people with dementia and their caregivers, Polsky noted.

In the pipeline are new disease-modifying pharmaceutical treatments for dementia, but they require an early diagnosis, which only a fraction of people receive. Should these treatments scale, it could cost the Medicare program tens of billion dollars a year, presenting an additional challenge to the already-strained Medicare budget. Implementing new early diagnosis techniques and providing cost-effective new treatments will present complicated hurdles for the health-care delivery system, Polsky suggested.

The more than 5 million family members and friends who provide unpaid care for older adults with dementia have high—and increasing—demands on their time, reported Jennifer Wolff of the HEADS Center, based on her team’s research using nationally representative data.

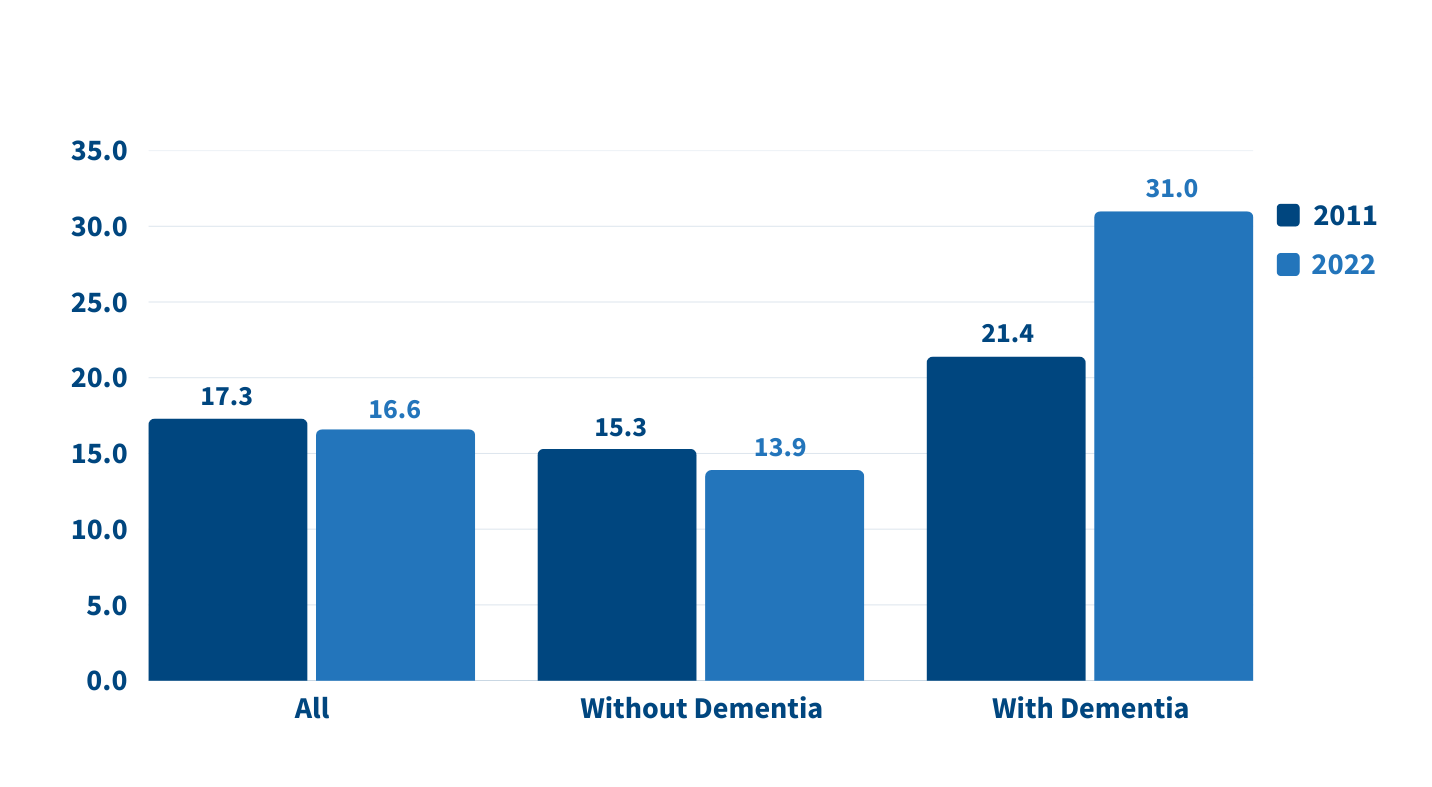

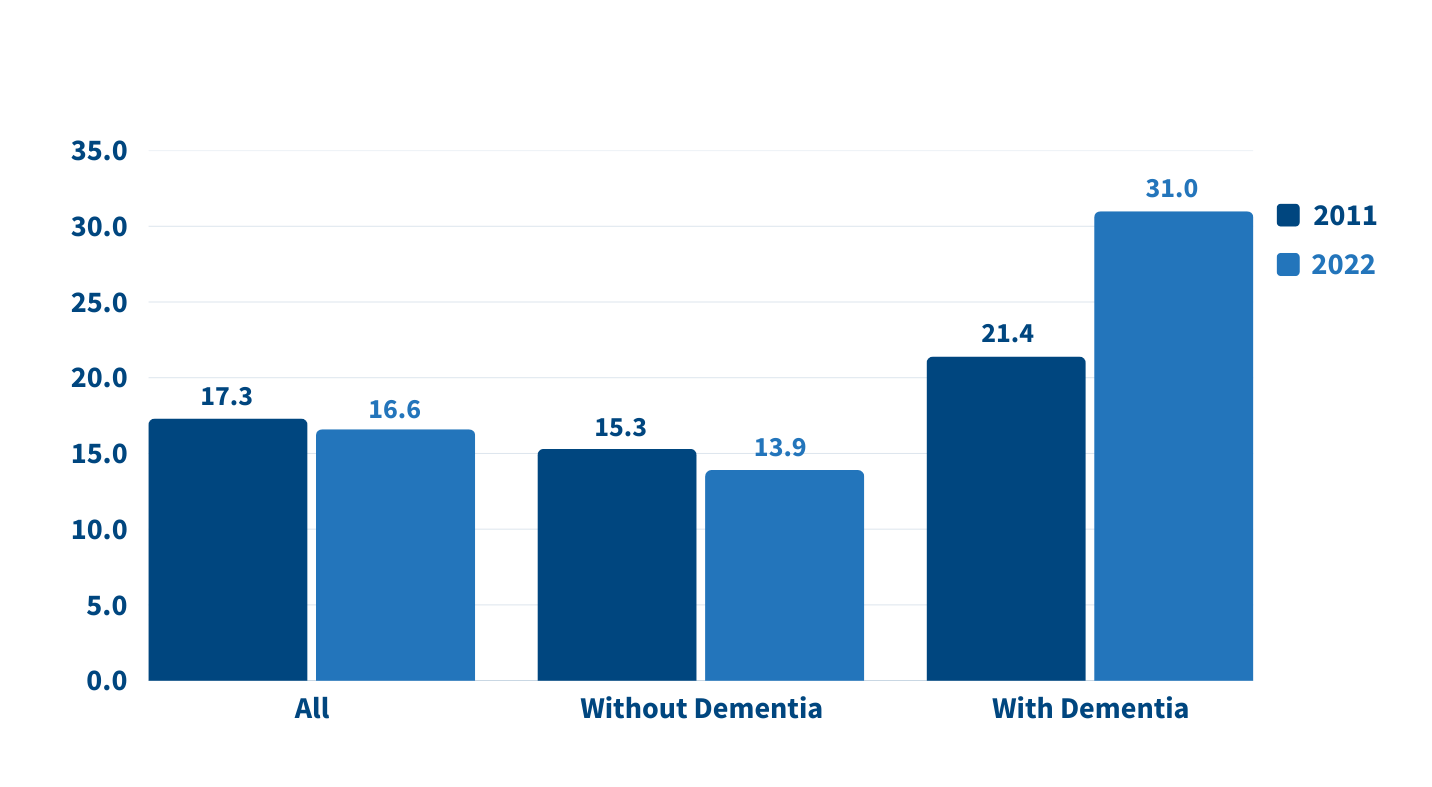

On average, the time that family caregivers spent helping older adults with dementia grew by almost 50% between 2011 and 2022, going from 21 hours per week to 31 hours (Figure 3). By contrast, time spent assisting older adults without dementia fell during the same period.

Wolff and team show that more than half (52%) of dementia caregivers lived with the person they were caring for in 2022, up from 39% in 2011. And the share able to hold jobs—outside their caregiving work—dropped from 43% to 35% during the same period.

Noting that the number of individuals affected by dementia is projected to triple in the next 30 years, Wolff underscored the importance of monitoring unpaid caregivers and developing interventions to support them. Some strategies could include providing direct financial assistance and tax relief, supporting flexible work arrangements and paid family leave, and using digital tools and remote monitoring technologies to help caregivers manage care more efficiently and connect with support networks.

Source: Jennifer L. Wolff, Jennifer C. Cornman, and Vicki A. Freedman, “The Number of Family Caregivers Helping Older US Adults Increased From 18 Million to 24 Million, 2011–22,” Health Affairs 44, no. 2 (2025): 189-95.

More devastating fires, storms, and hurricanes, along with greater climate variability are the “new normal,” said Elizabeth Frankenberg of the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

People who experience these events not only face an increased risk of death and disease but also lost livelihoods, diminished assets, and poor quality of life for months, years, and even decades to come, she noted.

Older people can be uniquely vulnerable due to reduced physical mobility, cognitive decline, diminished temperature regulation, and changes in economic resources, access to safety net programs, and the availability of social and family networks. Further, their ability to cope with change may be influenced by anxiety around uncertainty, a deep attachment to where they live, and difficulty making life-changing decisions.

To effectively plan for, mitigate, and adapt to severe weather events and temperature changes, demographers should team up with engineers to better understand the level of vulnerability in specific risky locations, Frankenberg said. For example, older people with lower incomes and limited mobility may need emergency support in places with rising sea levels or that are prone to wildfires.

The experts noted several promising areas for future research that can improve the health and well-being of older adults, including:

The researchers emphasized that many of these priorities require sustained investment in longitudinal data collection and interdisciplinary collaboration across aging research centers.

The scholars featured above lead many of the 15 research centers on the demography and economics of aging and Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer’s related dementias supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health for the past 30 years.

A coordinating center based at the University of Michigan supports the dissemination of findings from the centers in partnership with PRB.

Report from ARC and PRB finds decreased unemployment, increased labor force participation, and higher homeownership in Appalachia—but the Region still lags behind the U.S. in population and income growth, as well as post-secondary education attainment.

July 3, 2025

Senior Research Associate

Research Analyst

Senior Vice President, Programs

New data released by the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) and PRB in the 15th annual update of The Appalachian Region: A Data Overview from the 2019-2023 American Community Survey shows that rates of labor force participation and homeownership continue to improve in Appalachia.

Drawing from the latest American Community Survey and comparable 2023 Census Population Estimates, the report, known as “The Chartbook,” contains more than 300,000 data points comparing Appalachia’s regional, subregional and state data with the rest of the nation.

Key improvements in the region’s economic indicators are as follows:

Decrease in unemployment rates and higher labor force participation

Homeownership bypasses national average

Below average number of cost burdened households

“While Appalachia continues to make progress toward reaching economic parity with the rest of the country, it’s important to recognize there is still work to be done,” said ARC Federal Co-Chair Gayle Manchin. “ARC will continue to partner on the local, state, and federal levels to prioritize the future of Appalachia’s 13 states and remains committed to ensuring Appalachians have access to the education, job training and infrastructure they need for prosperous lives in the places they love.”

“This year’s Chartbook highlights important economic advances, not only in Maryland but across the Appalachian Region—including gains in employment and homeownership,” said ARC 2025 States’ Co-Chair, Maryland Governor Wes Moore. “By working together, we continue to uplift our most vulnerable populations, promoting a better, brighter future for all families across Appalachia.”

Despite positive trends, several data points revealed key challenges affecting Appalachian economies compared to the rest of the nation:

Despite population increase, growth lags

Post-secondary educational attainment remains behind national average

Greater share of Appalachians live in poverty

“The data point to bright spots but also guide us to areas where targeted efforts could improve well-being for Appalachians across the region,” said Sara Srygley, a senior research associate at PRB. “Decisionmakers and advocates can use the Chartbook to create the changes they want to see in their communities.”

The data shows that Appalachia’s rural areas continue to be at increased risk for economic distress compared to its urban areas. Appalachia’s 107 rural counties are also more uniquely challenged, compared to 841 similarly designated rural counties across the rest of the U.S., as rural Appalachian counties continue to lag behind on indicators including educational attainment and household income.

The data also highlights key differences between Appalachia’s subregions, including:

In addition to the written report co-authored by the Population Reference Bureau, ARC offers companion web pages on Appalachia’s population, employment, education, income and poverty, computer and broadband access, and rural Appalachian counties compared to the rest of rural America’s counties. For more information, visit www.arc.gov/chartbook.

About the Appalachian Regional Commission

The Appalachian Regional Commission is an economic development entity of the federal government and 13 state governments focusing on 423 counties across the Appalachian Region. ARC’s mission is to innovate, partner, and invest to build community capacity and strengthen economic growth in Appalachia to help the region achieve socioeconomic parity with the nation.

In the United States, over 24 million people provide unpaid care for older adults—a 32% increase from a decade ago

March 18, 2025

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

Contributing Senior Writer

As the large Baby Boom generation enters advanced ages, more family members and other unpaid helpers are stepping in as caregivers. In just over a decade, the number of family caregivers regularly assisting older adults with daily activities at home grew by 32%, increasing from 18.2 million to 24.1 million between 2011 and 2022.1

While the caregiving cadre has grown, who’s getting care has also changed. Older Americans receiving family care are younger, better educated, and less likely to have dementia than they were in 2011, report Jennifer L. Wolff of Johns Hopkins University, independent consultant Jennifer C. Cornman, and Vicki A. Freedman of the University of Michigan.

The increase in family caregiving partly reflects the rising share of older adults with multiple chronic conditions, such as heart disease, hypertension, stroke, and cancer. And while the share of older adults with dementia has declined, unpaid caregivers average twice as many hours each week caring for people with dementia than without dementia (about 31 hours versus 14), Wolff and team found (see Figure 1).

In addition, a new study estimates that the number of new dementia cases will double over the next 40 years as the population ages—setting the stage for more demands on dementia caregivers and more changes to the caregiving landscape.

“Understanding the changing composition and experiences of family caregiving has never been more important, but it is challenging to assess,” the researchers write. “[It] requires consistent measurement for well-characterized, generalizable samples of people who receive and provide help.”

The nationally representative National Study of Caregiving and the National Health and Aging Trends Study offer important insights. The two studies provide a snapshot of the family caregivers that help Americans ages 65+ who live in the community (i.e., at home or with a relative) or in a residential care setting other than a skilled nursing facility, such as an assisted or independent living facility, a personal care home, or a continuing care retirement community.

Family caregivers include relatives and unpaid helpers, like neighbors and friends, who assist with personal care tasks like bathing and dressing; mobility tasks like getting out of bed and getting around the house; and household activities such as laundry, food preparation, shopping, and managing money.

On average, the time that family caregivers spent helping older adults with dementia increased by almost 50% over the decade, rising from 21.4 hours per week in 2011 to 31.0 hours in 2022. By contrast, time spent assisting older adults without dementia fell from 15.3 hours a week in 2011 to 13.9 hours in 2022 (Figure 1).

Source: Jennifer L. Wolff, Jennifer C. Cornman, and Vicki A. Freedman, “The Number of Family Caregivers Helping Older US Adults Increased From 18 Million to 24 Million, 2011–22,” Health Affairs 44, no. 2 (2025): 189-95.

People caring for older adults with dementia have high—and increasing—demands on their time. More than half (51.7%) of dementia caregivers lived with the person they were caring for in 2022, up from 39.4% in 2011, Wolff and team report. And the share able to hold jobs—outside their caregiving work—dropped from 42.5% to 34.6% during the same period.

Among caregivers with formal jobs, the share who reported challenges with their employment—including working fewer hours or being less productive—increased over the decade, regardless of whether they cared for someone for dementia.

“Challenges are exacerbated when caregivers are in poor health themselves; have a lack of choice in assuming the caregiving role; and, for the substantial proportion of family caregivers who are employed, work in low-wage jobs with limited flexibility,” the researchers note.

Which older Americans get family care? As in the past, they tend to be female, non-Hispanic white women who are married or widowed. But growing numbers of family care recipients are male and have some college education. More are also separated and divorced compared to 2011, reflecting national trends.

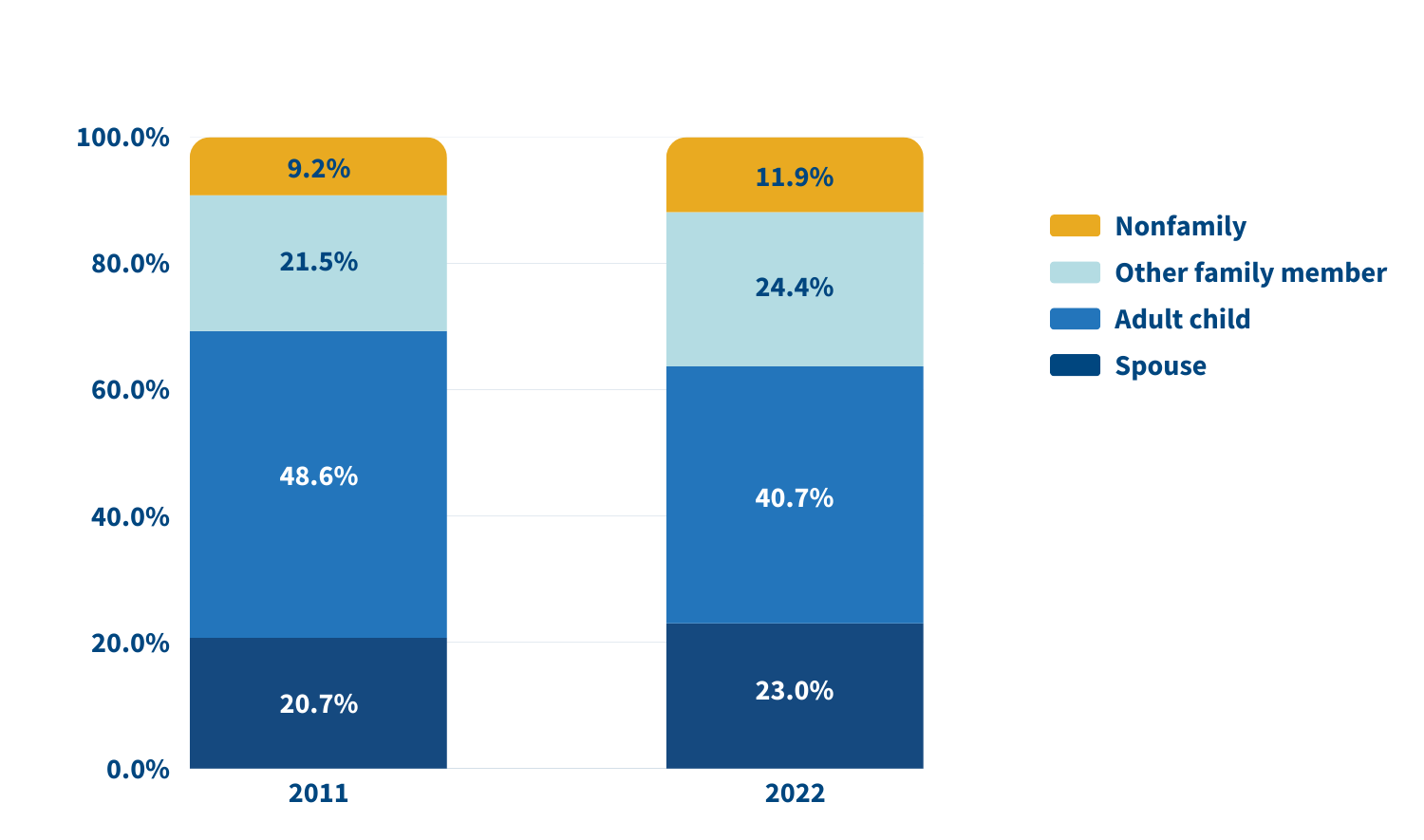

Who’s providing care? Family caregivers continue to be largely female and married, and most report being in good health. In 2022, adult children still made up the largest share of family caregivers for older adults, at 40.7%, but this represents a significant decline since 2011 (Figure 2).

Source: Jennifer L. Wolff, Jennifer C. Cornman, and Vicki A. Freedman, “The Number of Family Caregivers Helping Older US Adults Increased From 18 Million to 24 Million, 2011–22,” Health Affairs 44, no. 2 (2025): 189-95.

In 2022, adult children accounted for about half (49.1%) of family caregivers for older adults with dementia, compared with 38.4% of caregivers for those without dementia. Just 17.7% of family caregivers for older adults with dementia were spouses, compared with 24.5% of family caregivers for people without dementia.

A sizeable share of family caregivers (17.0%) had children under age 18 at home in 2022, and 6% to 13% viewed their care responsibilities for older adults as a source of financial, physical, or emotional difficulty.

Despite these challenges, the researchers report a decline in the use of support groups (4.1% to 2.5%) and respite services (12.9% to 9.3%) between 2011 and 2022.

Many caregivers face extraordinary demands and should be the focus of support services, Wolff and colleagues say. They single out those caring for older adults with dementia or nearing the end of life, as well as caregivers “from racial and ethnic minority groups who are more likely to assist people who have extensive care needs in circumstances that involve scare economic resources.”

Family care needs are likely to rise as the number of U.S. adults ages 85 and older is projected to triple by 2050. The researchers note that the number of family caregivers rose even as the long-term use of skilled nursing facilities among older Americans dropped and community living increased. The challenges these caregivers continue to face is “sobering,” they write, including competing time demands from work and child care while spending an average of 17 hours per week on care. In addition, about 1 in 8 family caregivers report financial, physical, or emotional difficulties related to their caregiving roles, percentages that were largely unchanged over the 11 years examined.

Policies and programs to help reduce the financial, physical, and emotional burden of caregiving exist, but do not represent a coherent strategy, the researchers say. “Local, state, and federal policies are a patchwork that is uneven in availability and largely symbolic in magnitude,” they argue. Addressing the needs of family caregivers will require a “cohesive framework in support of the care economy.”

1. Jennifer L. Wolff, Jennifer C. Cornman, and Vicki A. Freedman, “The Number of Family Caregivers Helping Older US Adults Increased From 18 Million to 24 Million, 2011–22,” Health Affairs 44, no. 2 (2025): 189-95.

March 18, 2025

In this March 4, 2025 webinar, three researchers discussed how social media and new technologies may enhance—or limit—social connectedness and emotional well-being among older adults.

This webinar was hosted by PRB and the Coordinating Center for the Centers on the Demography and Economics of Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias, with funding from the National Institute on Aging.

December 2, 2024

In this Nov. 14, 2024 webinar, two distinguished researchers discussed how U.S. state policies and systems can affect racial and regional inequities in health and longevity.

This webinar was hosted by PRB and the Coordinating Center for the Centers on the Demography and Economics of Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias, with funding from the National Institute on Aging.

Mark Mather, PRB: Hi everyone, thank you for joining today’s webinar on how state contexts impact Population Health. I am Mark Mather. I’m with the Population Reference Bureau, or PRB, and I work in collaboration with the Coordinating Center for the Demography and Economics of Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias at the University of Michigan. And our goal is to help publicize research on health and well-being, especially among older adults. I also want to acknowledge the National Institute on Aging for making this webinar possible, and my PRB colleague, Toshiko Kaneda, for helping us to organize this event.

I’m excited to introduce our two speakers today. We have Dr. Tyson Brown, who’s a Professor of Sociology, Associate Professor in medicine, and Associate Scientific Director of social sciences of the Duke Aging Center at Duke University and Dr. Jennifer Montez, who is a Professor of Sociology, Gerald B Kramer faculty scholar in aging studies, Director of the center for Aging and Policy Studies, and Co-director of the Policy, Place and Population Health Lab at Syracuse University.

We’re also going to put two links in the chat, I’m not going to read their long bios, but if you’re interested in learning more about the speakers and their research, we will be putting links in the chat where you can get more information. And finally, just a couple of housekeeping notes; we’re going to hold the Q&A until the end. But if you do have a question, you can type it into the Q&A box at any time during the webinar. And finally, this webinar is being recorded, we will send you a link to that recording after the event, probably within a day or two. And with that, I will go ahead and turn it over to you, Tyson.

Dr. Tyson Brown, Duke University: Well, thank you so much. I look forward to hearing your feedback during our presentation. I will go ahead and just start sharing my screen. Again, thank you so much for inviting me to present my work, and I’m really excited to talk with you all today about how we can operationalize state level structural racism and its impact on population, health and aging. And as a race scholar, gerontologist, and population health scientist, you know, the primary focus of my research is on quantifying and mapping structural racism, as well as estimating its impact on aging and health equity. And so today, I’ll be giving an overview discussing what I see as important theoretical and methodological issues, as well as promising avenues to address them, and in doing so, advance the scientific study of structural racism and health.

So, before discussing the role of states, I think it’s really useful to zoom out to highlight how various frameworks can help us better understand how social context influence health. So, the social ecological model emphasizes that population health is shaped by complex interplay of social factors across multiple levels, from individual behaviors to broader societal forces. And this model highlights how health outcomes are not solely a product of individual choices, but are influenced by interpersonal relationships, community structures, institutional policies, and broader sociopolitical contexts. And by analyzing each of these, we gain insights into how policies, societal norms, and community structures can either benefit or harm population health. And this is true for many social forces, including structural racism.

And so, most of the research on links between structural racism and health have focused on structural racism at the neighborhood or the county level, which are really important context and really sort of the micro-level, or rather the more proximate contextual sources or determinants of health. However, other special units and policies such as states have received comparatively less attention. And this is a really major limitation in literature, because U.S. states obviously are important legal, administrative and political units and states have always provided an important context for racial stratification, including the roles that they most obviously played with respect to chattal slavery, Jim Crow and anti-miscegenation laws. So importantly, states continue to have a great deal of autonomy, and they’re heterogeneous in terms of the racialized policies and practices. This is evident with respect to things like disenfranchisement laws, aggressive policing practices, punitive sentencing, as well as the expansion or contraction of safety net resources.

And so, as a result, my research focuses on conceptualizing states as racialized institutional actors that influence population health.

So, in several recent studies, my research team scopes the literature on social racism to really identify the central tenets of structural racism theories and draw upon them to study state level structural racism. We highlight how the analytical crux for measuring structural racism, which is a complex, interconnected and dynamic network, really lies in examining its features and mechanics that undergird racial inequalities.

And so, failure to align measurement tools with these core features compromises the validity of research. Because measures that are incongruent with salient aspects of structural racism can distort findings. So, to address this issue, we draw on interdisciplinary theories and evidence to really dissect core features of social racism, with a focus on their implications for measurement and modeling.

And so, our studies on and the broader literature really underscore the importance of measuring modeling core features of structural racism, including things like the fact that it’s a distributional system, involves relational power dynamics, manifestations of racial inequities, that it’s a multi-level phenomenon operating at macro and micro level contexts, that it’s multifaceted and interconnected in nature. And this plays out across societal domains, that there are specific racial actors implicated, that it’s an institutionalized phenomenon that it involves racial schemas, logics, as well as socio historical context and intersections with other systems of oppression. And so structural racism is embedded in major political, economic, medical, criminal, legal and numerous other social institutions and aspects of society. So, in these forthcoming articles that are listed here, we offer concrete recommendations for conceptualizing, measuring, and modeling structural racism in ways aligned with theory. And so, the aims of these studies is to provide field guides for rigorous, theory driven measurement approaches, proposing best practices for the scientific study of structural racism in health research.

And to provide a couple concrete examples of ways to measure structural racism, as well as its effects on health, I’ll briefly describe several recent studies in this vein. And so, the first one addresses two main research questions. The first is, does state level structural racism across societal remains reflect an underlying latent construct? And latent constructs are phenomena that are not directly observable but can be estimated through statistical approaches that really capture manifestations of the phenomena. And then secondly, the question is structural racism associated with worse health outcomes among Blacks and whites in the U.S.

So, to examine variability in state level structural racism and its relationship with health among Black and white adults, we combined indicators of structural racism from several sources of publicly available data. And then we link these to geo coded individual health and demographic data from the Health and Retirement Study, as well as CDC data on COVID mortality, as well as the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance study. And so, this table shows each of the domains and indicators of structural racism that we examine. We use publicly available data to examine structural racism for the year circa 2010, spanning several domains including the criminal legal system, education, economic resources, political participation, as well as residential segregation.

And so, I should mention that this measurement approach is informed by theoretical perspectives as well as previously validated measures of state level structural racism.

So, the next step is to test whether state level structural racism reflects this underlying latent construct. And so, we’re especially interested in measuring structural racism in ways that are in line with structural theories, as I mentioned. And a latent variable approach is well suited for minimizing measurement error and capturing conceptual properties of a complex system that’s difficult to quantify or directly measure, such as structural racism. And so along those lines, the nine indicators of structural racism that I mentioned were used to develop a latent measure of structural racism. And we used confirmatory factor analysis to measure the extent to which structural racism across these domains are reflective of an underlying construct of structural racism and doing so we systematically evaluated model fit using varying model specifications related to correlated errors and also dimensionality. This figure here illustrates the factor structure of the latent construct. These correlated errors are all intended to address common sources of variation that are independent of the effects of structural racism on the various indicators. And so all consider the measurement model that allows for other common sources of variance in the indicators that are largely conceptually motivated, has a good fit with the data, and it generates reasonable parameter estimates. Furthermore, this measurement approach is largely consistent with many of the theoretical tenets that I outlined above. And I should note that we made this measure publicly available from the journals website in case you’re interested in exploring. So now we’ll turn to addressing the second research question, which is how does structural racism shape health among Black and white adults? Eco social theory has become a leading framework for understanding how macro level discriminatory environments impact health, and the theory suggests that structural racism has deleterious effects on Black people’s health. That part’s pretty much straight forward. We would anticipate that from the theory. And there are competing hypotheses about how structural racism may influence the health of whites, with some suggesting that whites benefit from sexual racism, while others are positing that they’re harmed by it, and others suggesting that their health may be unaffected by structural racism. I’m glad to talk more about these competing hypotheses during in more detail during the Q&A, if you’d like.

But let’s go ahead and jump into the results. What’s going on here? I’ll explain it in just a second. But one of the things I want to mention is that, you know, since replication is a hallmark of good science, we examine the relationship between structural racism and six different health outcomes in both the Health and Retirement Study and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance study. For a little bit of context, the HRS is considered one of the premier data sources for studying health among adults over the age of 50 in the U.S. is nationally representative over samples of Black adults and the birth. This is the largest health survey in the in the United States. So, you have over 300 respondents. So, you’ve got tremendous statistical power. And so, we found remarkably consistent results across health outcomes and across the two data sets. And six out of the six cases, you can see that there are that higher levels of structural racism are predictive of worse health among Black people, remarkably consistent. But we see a very different story for whites. And one instance, structural racism exposure at the state level is predictive of better health for whites and in five out of six cases, there is no statistically significant relationship between structural racism and whites’ health. So, you find, you know, shockingly consistent results and just, you know, these health outcomes are some of the most commonly used, especially when studying older adults. And so, I think that there’s this, you know, there’s a real signal that we’re picking up. And we had much more confidence in our findings because it was so consistent across these health outcomes and across these health studies. So, in a recent study, we also examined the relationship between a latent measure of structural racism and Black-white inequities in Covid 19 mortality rates. Right.

So, the regression estimates indicate that the relationship between social racism and Black, white inequality in Covid 19 mortality is positive and statistically significant, both in the bivariate model and net of covariates. And so, this again is a state level measure and collectively the findings you know, I would argue that the collectively our findings across these studies suggest that our latent variable approach has really strong predictive validity and we actually did measure it against benchmarked it against other metrics such as sort of a summative index that assumed equal weighting of the indicators and did not take into account correlations between their errors when we found that the latent measure actually explained more variation in health outcomes and also explained significantly more variation of any of the individual level indicators. And so that again, provides some evidence that there’s really there are some real benefits to taking a latent measurement approach. So, I think it’s also essential to measure and map cultural forms of racism that reflect racial schemas, logics and practices.

So broadly you know, we really need to be considering the roles of things like racialized violence, animus, resentment, hate speech, and biases, all of which have been shown to vary by place including across states. And so, in addition to well-established survey data resources, we should also be utilizing data and methods to capture utilizing, you know, more innovative data measures to capture anti-Blackness through geo coded data from things like internet search engines and computational approaches, scraping websites and even experiments. So, this map shows the spatial distribution of a latent measure that Reid DeAngelis and I are developing using these types of data and measures. And preliminary results show that it’s predictive of population health inequities. And so, we’re really encouraged about the possibility of combining these latent measures of racial schemas and logics, sort of cultural measures with the more institutional measures and looking at how the interplay between them and their relative contributions to population health inequities.

I should also mention that in a recent study published in the Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Patricia Home and Brittany King and I, we introduced a state level structural intersectionality approach to population health. And what it does is it really demonstrates an application of social intersectionality using administrative data sources similar to the ones that I discussed in the previous studies. To examine the relationship between macro level structural racism as well as structural sexism and economic inequality and looking at how they interplay between them, as well as their joint and individual contributions to health inequities across U.S. states. Right. And so, this study, I think, can really serve as a springboard and a data source for similar studies that are aiming to extend this research, in studying how state level structural, intersectional oppressions differentially shape health outcomes for various demographic groups. I should also note that numerous studies also really highlight the dynamic role that policies and politics play in shaping health inequities.

Obviously, Jennifer Montez is a new data set, is an excellent resource for studying the role of states in this regard. There are also some studies by biomedical engineer Jackie John and other colleagues that used novel, a novel database on racism related laws which has been shown to predict health. So, these and other data sources on racial policies such as three strikes laws, welfare reform, banning critical race theory and racialized disenfranchisement can really serve as important resources for research on health inequities. And, you know, the history of structural racism in the U.S. has really important implications for how we should really be approaching the measurement of it and quantifying its effects on these inequities. And there is suggest that historical racism directs, constructs and continues to mold contemporary structural racism as well as health outcomes. And so, in that vein you know, there have been several empirical studies that have shown that polities that had larger enslaved populations in 1860, have greater present-day inequities and poverty and economic mobility and also higher levels of contemporary pro-white bias, and that these can be linked to contemporary health outcomes as well, and that historical redlining practices underlie contemporary residential segregation patterns. This is becoming a well-documented social fact, as well as the fact that New Deal policies expanded the white middle class and are directly implicated in modern Black-white inequities and wealth. And so, it really shows the long arm of history in shaping contemporary health outcomes and moving forward. I think a couple of examples of measures to consider include variation and exposure to things like slavery, Jim Crow, lynchings, anti-miscegenation laws, stunned downtowns, the number of folks who are doing really good work in that space. We can think about exclusion from the economic benefits of the New Deal and GI bills, as well as racialized voter suppression.