HoPE-LVB Project Evaluation Webinar

Pathfinder International and partners in Kenya and Uganda have implemented the Health of the People and Environment in the Lake Victoria Basin (HoPE-LVB) project since 2011.

The project aims to scale up its use of the population, health, and environment (PHE) community-development model at local, national, and regional levels by integrating PHE considerations in formal government development planning and policies. “PHE” refers to the PHE approach, which aspires to increase access to comprehensive reproductive health services and improve maternal and child health care practices while simultaneously improving natural resource management in project communities.

HoPE LVB Project Evaluation Webinar 2019 04 30 09 02

On April 30th, 2019, HoPE-LVB project implementers and evaluators discussed the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) evaluation report on the model’s effectiveness and scalability. Released in April 2018, the USAID report addresses three key questions:

What are stakeholders’ perceptions of the HoPE-LVB project model’s added value to family planning and reproductive health, maternal and child health, livelihoods, governance, natural resources management, or conservation?

Has the HoPE-LVB project’s explicit focus on systematic planning for scale-up resulted in positive outcomes for the model’s institutionalization, sustainability, and expansion?

To what extent did the HoPE-LVB project achieve its objectives as measured by its key performance indicators/results?

The evaluation of HoPE-LVB had been long anticipated, as the project was supported by cross-sectoral investments by multiple donors and represents a pioneering East African PHE project implemented at scale.

The webinar, scheduled at 9:00 a.m. EST on April 30, 2019, was hosted by the PACE (Policy, Advocacy, and Communication Enhanced for Population and Reproductive Health) project. It included the following speakers:

Clive Mutunga of USAID provided introductory remarks on USAID’s support for PHE models globally and what USAID learned from the evaluation of HoPE-LVB.

Eileen Mokaya of Pathfinder International provided an overview of the HoPE-LVB project.

Richard Kibombo of Global Health Program Cycle Improvement Project (GH Pro) shared the evaluation’s results and his suggested next steps for PHE sustainability and scale-up.

Featured Resources

View More

16 Days of Activism Against Gender Violence

(November 2012) The 16 Days of Activism Against Gender Violence is an international campaign originating from the first Women’s Global Leadership Institute sponsored by the Center for Women’s Global Leadership at Rutgers University in 1991. Participants chose the dates, November 25, International Day Against Violence Against Women, and December 10, International Human Rights Day, in order to symbolically link violence against women and human rights, and to emphasize that such violence is a human rights violation.

The theme for 2012 continues the theme from 2011, “From Peace in the Home to Peace in the World: Let’s Challenge Militarism and End Violence Against Women”; describes the complex relationship between peace, home and the world; and recognizes the many spaces where militarism influences our lives.

As part of a multiyear campaign theme on the intersections of militarism and violence against women, this year’s 16 Days Campaign has three subthemes:

- Sexual and gender-based violence committed by state agents, particularly the police or military

- Proliferation of small arms and their role in domestic violence

- Sexual violence in and after conflict

For more information on the 16 Days of Activism and to access a Take Action kit, see: http://16dayscwgl.rutgers.edu/.

Distilled Demographics: How Many People Have Ever Lived on Earth?

Updated

“Distilled Demographics,” PRB’s video series, highlights key demographic concepts such as fertility, mortality, and migration. Through these short videos, you can learn demography’s real-world application and impact. “These videos not only show that demography can be exciting, but also highlight how population trends and issues affects the well-being of us all,” says Carl Haub, senior demographer at PRB. “Fertility, mortality, and migration—along with other demographic issues—play a major role in determining what kind of opportunities and challenges people face in their communities and countries.”

This video accompanies “How Many People Have Ever Lived on Earth?” one of PRB’s most popular articles, first published in 1995 and updated in 2002. This latest update includes data up through mid-2011.

The question of how many people have ever lived on Earth is a perennial one among information calls to PRB. One reason the question keeps coming up is that somewhere, at some time back in the 1970s, a writer made the statement that 75 percent of the people who had ever been born were alive at that moment. This factoid has had a long shelf life, even though a bit of reflection would show how unlikely it is. For this “estimate” to be true would mean either that births in the 20th century far, far outnumbered those in the past or that there were an extraordinary number of extremely old people living in the 1970s. If this estimate were true, it would indeed make an impressive case for the rapid pace of population growth in this century. But if we judge the idea that three-fourths of people who ever lived are alive today to be a ridiculous statement, have demographers come up with a better estimate?

In this video, PRB senior visiting scholar Carl Haub, with some speculation concerning prehistoric populations, approaches a guesstimate of this elusive number.

PRB’s Distilled Demographics video series is underwritten through the generosity of Juanita Tamayo Lott and Robert H. Lott in support of PRB’s Millennial Generation Outreach Program, and in memory of Jorge del Pinal.

The U.S. Decennial Census and the American Community Survey: Looking Back and Looking Ahead

(April 2011) On March 24, 2011, the U.S. Census Bureau released the final 2010 Census redistricting data files for each state that will be used to redraw federal, state, and local legislative districts. Although the 2010 Census data are still new, the Census Bureau has already started evaluating the data and planning for the next decennial census in 2020.

As part of PRB’s Policy Seminar series, Robert Groves, director of the U.S. Census Bureau, and Frank Vitrano, associate director for the 2020 Census, discussed the quality of the 2010 Census, the future of the American Community Survey (ACS), and early plans for the 2020 Census. View their PowerPoint presentation.

In the first half of the seminar, Groves described several ways to measure the quality of a census, and shared some early indicators of the quality of the 2010 Census data. One evaluation method is to compare census results to alternative estimates such as those from the Census Bureau’s Demographic Analysis program or their annual population estimates program. Groves noted that the 2010 Census count of total U.S. population was very close to both the middle estimate from Demographic Analysis and the vintage 2009 population estimates. In addition, at the state level, the percent difference in total population between the census count and the annual population estimate was much smaller for the 2010 Census than it was for the 2000 Census. Groves also described several positive indicators of the quality of Census 2010 data collection processes, such as fewer duplicate records (people counted twice) and a higher share of records with usable data.

There were changes in some census operations that also seemed to have improved data quality in 2010 compared with 2000. For example, distributing bilingual questionnaires to Spanish-speaking households and sending replacement forms in hard-to-count communities increased participation rates. The Census Bureau also used real-time evaluation in the 2010 Census. When results from a precensus survey showed that 18-to-24-year-olds were not inclined to participate in the census, the bureau ramped up their digital advertising campaign in the days prior to April 1 (Census Day) to boost response rates. The 2010 short-form design also appeared to be effective—there was a participation rate of 72 percent compared with 69 percent using the combined short/long form design in 2000. Finally, Groves observed that the availability of high-quality enumerators—due to the recession—may also help explain the improved results in 2010.

The Census Bureau’s post-enumeration survey is another important evaluation tool, used to measure census undercount and which population subgroups were most likely to be missed. Final post-enumeration survey results will be released in 2012. Researchers can also use estimates from the ACS to help interpret the 2010 Census results and put the numbers into a broader social and economic context.

In the second half of the seminar, Frank Vitrano discussed the future of the decennial Census and the ACS, and outlined early plans for 2020. The cost of the census has been rising rapidly since 1970, and one of the primary goals for the 2020 Census is to reduce cost. Vitrano described four key cost drivers:

- Increased population diversity and decreased willingness to participate in the census or respond to nonresponse follow up.

- Limited intercensal updates of address files and maps, leading to last-minute changes.

- Failure to effectively manage and continuously update decennial census planning, schedule, and budget.

- Rising costs of producing high-quality data, and stakeholder demands for data that are 100 percent accurate.

Vitrano presented several potential measures to reduce costs, including expanding and automating self-response methods, adding an Internet option, and using administrative records for follow up. Administrative records could potentially fill in some of the data gaps for households that cannot be reached through traditional methods. He outlined potential improvements in program management, budgeting and scheduling and noted the need to build consensus among stakeholders regarding the tradeoff between accuracy and cost.

The Census Bureau is currently considering six designs for the collection of 2020 census data, including three alternatives for information technology infrastructure. Vitrano noted that key decisions must be made by 2015 in order to avoid increased risk and cost due to late design changes.

Redistricting data from the 2010 Census are available through the Census Bureau’s American FactFinder website: http://factfinder2.census.gov/main.html.

For a schedule of data to be released from the 2010 Census, visit the Census Bureau’s website: www.census.gov/population/www/cen2010/glance/index.html.

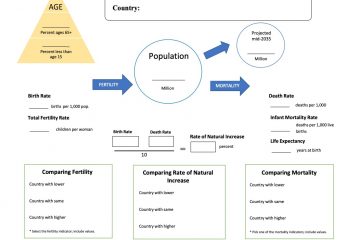

Distilled Demographics: Population Projections

“Distilled Demographics,” PRB’s video series, highlights key demographic concepts such as fertility, mortality, and migration. Through these short videos, you can learn demography’s real-world application and impact. “These videos not only show that demography can be exciting, but also highlight how population trends and issues affects the well-being of us all,” says Carl Haub, senior demographer at PRB. “Fertility, mortality, and migration—along with other demographic issues—play a major role in determining what kind of opportunities and challenges people face in their communities and countries.”

Everyone wants to know what the world’s population will be in the future, but how do demographers come up with population projections? It’s important to understand the assumptions behind projections—the factors that are considered such as the current birth rate, contraceptive use, education levels, policy and funding, and more. In this video, PRB senior visiting scholar Carl Haub uncovers how demographers estimate what the population of a country or the world will be in the future.

PRB’s Distilled Demographics video series is underwritten through the generosity of Juanita Tamayo Lott and Robert H. Lott in support of PRB’s Millennial Generation Outreach Program, and in memory of Jorge del Pinal.

International Women's Day: 100 Years

Date

March 1, 2011

Author

PRB

(March 2011) March 8, 2011, marks the 100th anniversary of International Women’s Day. The past 100 years has witnessed much progress but there remains an unfinished agenda in many regions of the world. International Women’s Day traces its roots back to the second International Conference of Working Women held in Copenhagen in 1910. Over 100 female delegates from 17 countries voted unanimously that every year, in every country, the same day should be observed to call attention to their needs. The first International Women’s Day was launched the following year in 1911, nearly a decade before women in the United States would even have the right to vote.

International Women’s Day has taken on a broader meaning for women in both developed and developing countries. Thanks to the growing international women’s movement, bolstered by four global United Nations women’s conferences, the day now signifies a time to build support for women’s rights and equality in a number of arenas, including education, economics, and politics. The theme of this year’s International Women’s Day is “Equal Access to Education, Training, and Science and Technology: Pathway to Decent Work for Women.”

Gender equality and the empowerment of women are at the heart of many national and international commitments, including the UN Millennium Development Goals, but progress has been uneven and sluggish. While some developing regions have reached or are approaching gender parity in youth literacy and secondary school enrollment, challenges lie ahead for many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, and Western and South Central Asia.

Despite legal means, early marriage (before the age of 18) persists, along with the associated risks of adolescent childbearing. Early marriage can also curtail the opportunities girls may have for education. In countries and regions with the highest proportions of early marriage, girls’ educational attainment is adversely affected. Literacy rates, primary school completion, and secondary school enrollment are all lower than that of boys.

In developing countries, 35 percent of women ages 20 to 24 report having been married by age 18. And, in the poorest regions of the world, according to The World’s Women and Girls 2011 Data Sheet, the proportion is even higher, with levels ranging from 45 percent in South Central Asia to nearly 40 percent in sub-Saharan Africa. Nine countries have prevalence rates above 50 percent.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the total fertility rate (TFR) is 5.2 children per woman, the highest of any world region. But, in countries such as Mali, Niger, Somalia, and Uganda, where use of family planning is relatively low, the TFR is closer to seven children per woman. Lack of partner support is often cited as a reason for not using family planning, more evidence of women’s lack of decisionmaking power.

In Kenya, for example, the TFR is 4.7 children per woman. However, even in the same country, women and men have diverse views about ideal family size, ranging from three children among women in the wealthiest 20 percent of the population, to six children among men in the poorest 20 percent.

There have been many successes to celebrate over the last hundred years, but challenges still remain in overcoming barriers to gender equality. International Women’s Day is an occasion to look back on past struggles and accomplishments, look forward to the opportunities that await future generations of women, and continue to work for meaningful change.

Donna Clifton is communications specialist, International Programs, and Charlotte Feldman-Jacobs is program director, Gender, at the Population Reference Bureau.

PRB Discuss Online: Have Reproductive Health Voucher Programs Improved Equity, Efficiency, and Impact?

(January 2011) Vouchers are frequently mentioned as a promising alternative finance mechanism to achieve a variety of goals in health systems and reproductive health services. Do vouchers work? Ben Bellows and co-authors reviewed the literature on vouchers to identify reprod2011) Vouchers are frequently mentioned as a promising alternative finance mechanism to achieve a variety of goals in health systems and reproductive health services. Do vouchers work?uctive health programs and to determine the extent to which these programs have been evaluated. Findings were generally positive, but much remains unknown about program operations. How important are governance structures? What happens as voucher programs go to scale? How can challenges with fraud and poor information systems be overcome? Do programs reach the poor? Do providers really face competition for clients? In a PRB Discuss Online, Ben Bellows, associate with the Population Council and co-author of “The Use of Vouchers for Reproductive Health Services in Developing Countries: Systematic Review,” answered questions from participants about program design and performance for reproductive health vouchers.

Jan. 18, 2011 1 PM (EST)

Transcript of Questions and Answers

Joan Healy: Question One: In one country (Cambodia) using this system, providers complained about how long it takes for them to get reimbursed by the gov’t for the voucher after the service has been provided. This was in the early phase of introduction so this might be resolved now. Question Two: In India, community based workers are supposed to get reimbursed for bringing the woman in for the free delivery services. They do not get reimbursed until after the delivery. These community workers must then spend hours at the facility in order to get reimbursed. This is not feasible given these community workers oftentimes have small children who accompany them to the facility.

Ben Bellows: Hi Joan, Great questions. Yes, reimbursement is a key component in voucher projects and most projects experience some difficulties and delays as they learn to properly carry this out. In the Uganda STI voucher project for instance, some rural providers will delay filing claims, preferring to ‘batch’ them when transport to town is available. There’s mention of reimbursement issues in Melissa Densmore’s stakeholders paper (www.melissadensmore.com/papers/ictd09-mho-stakeholder.pdf). Delays on the voucher management agency side can reduce confidence in the project. In your India example, one can imagine that the situation could remain suboptimal if there are relatively few facilities for community workers to refer clients to. Community workers have little choice in where clients go and facilities have little incentive to be more responsive to clients and community workers. In voucher projects that use claims reimbursement, the review process needs to be timely for providers who operate on a cash basis. Claims review should be transparent and quick. In the Uganda STI project, we saw a reduction in processing time and fewer claims rejected as providers and VMA both learned from their experience over time.

Mary Lyn Gaffield: Do vouchers have an impact upon increasing access to family planning for women who have given birth within the past 12 months? And, are data available to show whether or not vouchers reduce unmet need among these women?

Ben Bellows: Hi Mary Lyn, Thank you for this question. In the Kenya Voucher project, there has been a noted increase in estimates of district level contraceptive prevalence among users of intrauterine device (IUD). I don’t know what proportion of these clients were women who had given birth within the past 12 months. If you’re interested, we could probably estimate that proportion based on subnational demographic data. Uganda is beginning a new long term and permanent methods voucher project and this will be something to measure on the claims form. One of the useful characteristics of many voucher projects is the use of a claims form that records a few variables of demographic, socioeconomic and spatial data that allows for a richer description of the client population.

Kennedy Ongwae: Hi Ben and colleagues, From your work with voucher schemes, do we know the main “drivers” of success of the schemes in achieving the desired impact? Issuing vouchers to users to access free or subsidised care? or more resources to the service providers? Depending on how you would define “going to scale”—do we have voucher schemes that have been scaled up and become part of the health care systems with substantial funding from Government budget?

Ben Bellows: Hi Kennedy, Great to see you on this forum and thanks for the question. National ownership of the program is a key driver for long term sustainability. As you know from the Kenyan experience, there are voucher champions who have made output-based initiatives in Kenya, like vouchers, part of the long term national development strategy (see “Vision 2030”).

Another key driver would be evidence that these projects can have an impact on utilization, out of pocket spending, facility quality, facility efficiency, and population health status. To date, those studies are few, but there are prospective studies planned or currently underway in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Bangladesh, Cambodia, and several other countries and literature reviews of past studies (see the Council’s RH Voucher project website: www.rhvouchers.org). This PRB talk includes a link to a recent systematic review on reproductive health vouchers. DfID, 3ie and AusAID are funding other reviews on related healthcare finance issues and once these studies are available, we’ll have a much better idea where vouchers and other finance strategies offer value.

As for projects going to scale, the historic examples from Taiwan and South Korea in the 1960s and 1970s were both national initiatives with substantial funding from Government (the same Council systematic review we just completed draws evidence from the Taiwan and Korea programs).

Tanja Kiziak: 1. Are voucher programs an effective instrument to reach poor women in rural areas? 2. What are the best ways to distribute the vouchers—and how can it be ensured that only those entitled to the services (i.e. the poor) are given the vouchers?

Ben Bellows: These are great questions. Voucher programs can be a great mechanism to reach rural disadvantaged populations (including poor women) and voucher programs have been found to be successful in increasing healthcare utilization among rural populations. For example, the western Uganda program reaches rural communities across 20 districts and the two reproductive health voucher programs in Kenya have significant rural coverage. Voucher programs can include a transport reimbursement (Bangladesh and Cambodia are two examples) that help rural populations reach proper care.

There are three common strategies to distribute vouchers. Entire districts or counties or neighborhoods can qualify. This is called geographic targeting and has been used in western Uganda in several subdistricts and in Nicaragua in barrios near to schools (for adolescent health vouchers) and in red light areas to encourage commercial sex workers’ use of sexual health services. The second way is to use a simple standard poverty test or risk assessment. This selects beneficiaries based on standard criteria, such as the “below poverty line” (BPL) card in India. The third method involves locally determined criteria, using for instance measures of poverty that are agreed by the community. In all three strategies a decision is made to either distribute vouchers for free or charge some fee. The western Uganda program has sold STI treatment vouchers through drug shops. In Nicaragua, vouchers with a short term expiry were given for free. For the maternal care programs in Uganda and Kenya, community based workers sell the voucher at a very low price to clients who qualify. Only the poor are permitted to purchase the voucher. Community sales agents are required to conduct home checks to confirm the client does indeed qualify.

Awa Minteh: In my country there are not such programes. I would like to know if they have really worked in other countries where it is being implemented. I have developed interest in Reproductive Health, especially among teenagers. how do one identify reproductive health problems and design programs that can best address them.

Ben Bellows: Your question raises a good point. There is need for materials to guide needs assessment and setting up new programs. The World Bank produced a “Guide to Competitive Vouchers” in 2005. You can find a copy of the World Bank guide and related resources about a Nicaragua voucher program for adolescent sexual health on this website: www.icas.net/new-icasweb/english/en_pubs.html. The Population Council has managed a “Friends of Youth” program in Kenya for a number of years that has included adolescent sexual health ‘coupons’ redeemable at private providers in the community. More information is here: www.popcouncil.org/projects/61_KenyaFriendsOfYouth.asp.

Kibet Sergon: What are the possible sustainable financing mechanisms for the voucher programs or other modalities of social health financing. How can government take up such programs?

Ben Bellows: This is a difficult question as financing dynamics involve often a good deal of politics, which will vary from place to place. Donor funding can be direct as is the case in the German Development Bank (KfW) in Uganda and Kenya or indirect through basket or Sector Wide Approach (SWAp) funding in Bangladesh. When talking about national governments, programs could be financed from social insurance or tax-based contributions from Treasury. Either way, the voucher service links financial disbursement with service delivery. More information on financing strategies can be found at the Center for Health Market Innovations (http://healthmarketinnovations.org). Governments are taking up voucher programs. In Bangladesh the demand side finance (DSF) voucher initiative has been very popular. In fact, in the selection of new upazilas for a recent program expansion, the program managers were encouraged to include an extra upazila to satisfy requests from Government. In Kenya, the output-based approach (OBA), as realized in the voucher program, is a popular component in the government’s multisectoral strategy to achieve significant growth over the next 20 years (“Vision 2030”).

Earl Grandstaff: Why hasn’t articles come out in magazines on the 2010 census count?

Ben Bellows: I’m sorry, but I don’t have enough information to know which census this refers to.

Pradeep Bohara: what is the exact meaning of reproductive health??

Ben Bellows: This a good question and important to have agreement on definitions. The World Health Organization says the following: Within the framework of WHO’s definition of health as a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, reproductive health addresses the reproductive processes, functions and system at all stages of life. Reproductive health, therefore, implies that people are able to have a responsible, satisfying and safe sex life and that they have the capability to reproduce and the freedom to decide if, when and how often to do so. Implicit in this are the right of men and women to be informed of and to have access to safe, effective, affordable and acceptable methods of fertility regulation of their choice, and the right of access to appropriate health care services that will enable women to go safely through pregnancy and childbirth and provide couples with the best chance of having a healthy infant. From www.who.int/topics/reproductive_health/en. Wikipedia may be helpful here too: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reproductive_health.

Bakrr: Can developing countries governments impose RH methods to halt ethic differences in TFR. In one community variance is so great 9 against 2.4 which raised concerns of out-numbering?

Ben Bellows: Thank you for your question. No, governments should not impose RH methods to level total fertility rates in different populations. It would generally be considered a gross violation of human rights. RH programs are designed to meet the needs of individuals who voluntarily seek RH services. For reference, please see numerous statements from the United Nations on sexual and reproductive health rights: www.un.org/ecosocdev/geninfo/women/womrepro.htm.

Pradeep Bohara: In the developing country, people think that, Reproductive health is the Issue of the female only, how to minimize such type of thinking??

Ben Bellows: This is an important question addressing male involvement in reproductive health (RH) services and RH decisions. There are a good number of governments, donors, NGOs and others engaged in generating greater male involvement in family planning. USAID has funded many programs. I don’t have the papers available, there are a good number of papers on male involvement in pregnancy, family planning services and other RH issues. Two examples linked here: USAID www.usaid.gov/our_work/global_health/pop/news/amman.html and Population Council www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/frontiers/orsummaries/ors45.pdf. Vouchers can be a useful mechanism to get partners discussing RH issues. In the Uganda STI Voucher project, the voucher is sold to the client with half of the voucher available to the client’s sexual partner. This referral mechanism is very useful in settings were ‘contact tracing’ is not feasible response to STI epidemics. It can also encourage greater male involvement in cases where the woman bought the voucher.

Debbie Fugate: Could you provide citations for published studies on the issue of vouchers for RH that you would consider key?

Ben Bellows: The tables in this recent systematic review describe seven evaluations of 13 published voucher programs. The reference list is a rich source of citations: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02667.x/pdf. If you’re interested in program design options, please see the World Bank 2005 “Guide to Competitive Vouchers in Health” linked near the top of this page (Instituto Centroamericano de la Salud), where you’ll find other citations: www.icas.net/new-icasweb/english/en_pubs.html

Gillian Eva: Hi Ben, Could you clarify what the advantages are of using a voucher system over providing discounted or free services?

Ben Bellows: Hi Gillian, Great question. There are several advantages to using vouchers. On the demand side, clients have a physical reminder in hand to go to the facility. It’s the same reason retailers print coupons in newspapers. On the supply side, service use is linked to financial reimbursement. Even in ‘virtual voucher’ programs, the supply side benefits are available. In a good voucher program, information systems are in place to record medical and financial information about the clinical experience. Information systems are likely to be more complete in voucher programs that require clear and completed claims before payment is made. Perhaps the most useful distinction between voucher and free services is the targeting mechanism. For maternal delivery services, targeting poor women is important to reach those who may not otherwise consider a facility delivery.

For a good summary of a ‘virtual voucher’ program in Gujarat, India, please see this YouTube interview with economist April Harding: www.youtube.com/watch?v=eFfuGDDQreo.

Karin Ringheim: I’m interested in the issue of integrating Family planning (FP) into other services, particularly maternal and child health (MCH) services. Have you come across examples of where vouchers have been successfully used to encourage mothers to access FP within recently integrated FP-MCH programs? Thanks.

Ben Bellows: Hi Karen, this is a good question and timely given the strong interest in integrated RH/ FP services. The Kenya voucher program offers a FP voucher, a separate maternal care (safe motherhood) voucher, and a third gender based violence recovery voucher. In a recent review of the program, it was recommended to integrate FP services in an expanded maternal RH voucher.

Carrie Ngongo: In a world of constrained resources where we would like to see fewer women dying and injured in childbirth, what would you say are the pros and cons of a country establishing a voucher program for maternity services (targeting the poorest or most rural populations) vs. announcing free maternity services for all, such as the policy decision in Sierra Leone in 2010? I’m especially curious about cost and public health impact considerations.

Ben Bellows: Hi Carrie, Thanks this is a very topical question. Announcing free maternity services for all—without changing the underlying reasons for low service utilization—takes place only at public facilities and risks leaving mothers disconnected from the healthcare system. We know from past studies that even in countries like Sierra Leone maternal death is disproportionately concentrated among the very poor and rural populations—the very populations least likely to benefit from removal of user fees. In contrast, vouchers are targeted to women who need the RH service. Vouchers can be used to provide transport subsidies as is done in Bangladesh and Cambodia. Vouchers can bring funding to public and private facilities based on client demand. The combination of stimulating client demand and linking that with financial disbursements to both public and private facilities is very different from removal of user fees at public facilities only.

An added benefit of vouchers is that targeting can be improved over time. Determining if people other than the intended beneficiaries are using the service (“leakage”) can be measured with simple checks at a sample of facilities. One disadvantage to vouchers is that healthcare management must improve if the services are to be effectively delivered. Prompt information feedback is important in most systems and that certainly holds for vouchers.

Marcia Gomez: Thank you for all the reference and resources being shared! My understanding is that many funds for RH are being minimized worldwide (especially for contraception). Are voucher programs something that has been looked at in areas where funding may be limited for these services; in other words, can these services continue in particular to poor families if a voucher method is instituted?

Ben Bellows: Hi Marcia, many thanks for the question. If rationing funds for healthcare to the poor is a priority, vouchers can be an effective mechanism to ensure that the services are properly targeted to the poor. Like any program, however, there is an administrative cost and decisions may have to be made on the desired level of verification versus percentage spend on service delivery.

Rose Reis: Has the Gujarat scheme Chiranjeevi Yojana been replicated in other Indian states?

Ben Bellows: Hi Rose, Good to see you on the forum and good question. I haven’t seen the Gujarat Chiranjeevi Yojana program replicated. As background for readers, Bhat and colleagues describe the program in this paper in 2009: www.banglajol.info/index.php/JHPN/article/view/3367/2814. Checking the Center for Health Market Innovations database, I didn’t find similarly titled programs mentioned there although a blog post from last year suggested that it would be a potentially useful model to try elsewhere. Some of the state level JSY programs in India have used vouchers for community referral purposes. The WHO produced a good 2010 summary on how vouchers fit with other demand side finance strategies with some discussion on vouchers in Indian healthcare finance reforms: www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/27DSF.pdf.

Arin Dutta: What would be a good mechanism to integrate voucher schemes with non-governmental forms of health financing like community health insurance? The idea being that the voucher can still be used to generate choice and agency for the recipient, but the payments are settled from alternative sources. Are there any examples?

Ben Bellows: Hi Arin, Great question and thanks for posting. Vouchers use a targeting mechanism and give clients choice as you noted while contracting providers so vouchers could perhaps be used to expand uptake of community health insurance. I haven’t seen examples of this yet, but in Cambodia there are interesting health equity funds (HEFs) that have integrated vouchers with contracted health services. It’s perhaps the closest scenario in which vouchers are added to existing contracted services. Voucher-like cards will be used in Tanzania beginning later this year to encourage use of maternal health services in a pilot organized by the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) in the context of community health funds (CHFs). There may be disadvantages to vouchers in small community health insurance programs if voucher distribution or reimbursement bring more administrative costs.

Fertility and Infant Mortality Declines in Tanzania

(December 2010) Tanzania is one of the world’s poorest countries, with a 2008 annual per capita income of just $1,263, and nearly 90 percent of the population living on less than $1.25 per day.1 Maternal, infant, and childhood mortality—important indicators of overall socioeconomic conditions—are high, even for East Africa. But results from the Tanzania 2010 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) show considerable improvement in infant and child mortality and a modest decline in fertility.2 Some maternal health indicators show progress as well.

Between 1992 and 1996, about 88 of every 1,000 newborns died before their first birthday, and 137 of every 1,000 died before age 5. The 2010 DHS found the average infant mortality rate had dropped to 51 per 1,000—and the under-5 mortality rate to 81—in the five years preceding the survey. There are other clear, if less dramatic, signs that health has improved for women and children. There have been modest increases since the mid-2000s in the percentage of expectant mothers receiving prenatal care, injections against tetanus, and vitamin A supplements (which can prevent blindness). The vast majority see a medical professional at least once during their pregnancy. Although four visits are recommended, one visit means that most pregnant women are at least interacting with the health care system.

However, only 50 percent of Tanzanian mothers have the services of a skilled attendant during childbirth. While this is a slight increase from 46 percent in the 2004-05 DHS, it is not enough progress to significantly improve maternal health and reduce maternal mortality. Skilled medical care during childbirth reduces the risk of infection and other complications that threaten the health of both mother and child.

There is considerable variation in who uses skilled childbirth attendants. Mothers who are younger, have more education, and who live in urban areas are much more likely to have received medical care from a skilled attendant at childbirth. The DHS found that mothers with at least a secondary education were twice as likely to have skilled childbirth attendants than women with no education.

While the most recent estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO) show some improvement in maternal mortality in Tanzania, the WHO labeled it as “insufficient progress.”3 Although the ratio of pregnancy-related deaths fell from about 920 women per 100,000 births to 790 women per 100,000 between 2000 and 2008, Tanzania’s maternal mortality remains above the average for eastern and southern Africa (550 maternal deaths per 100,000 births in 2008).

Mothers Having Fewer Children

High maternal mortality usually goes hand-in-hand with high fertility, and Tanzanian women have a history of large families. In the early 1990s, Tanzanian women had about 6.3 children each, on average. Fertility has generally declined since then, with some fluctuations. The 2010 survey recorded the lowest level yet—5.4 lifetime births per woman—but it is too soon to tell whether this signals a sustained decline.

Fertility varies substantially among different groups of women. Women living on Tanzania’s large island of Zanzibar have about 5.1 children each. On the mainland, rural women have much larger families than urban women: 6.1 children compared with 3.7 children, respectively.

Family Planning Use Increases

Family planning use has increased among married women in Tanzania since the early 1990s and has played an important role in fertility decline. But family planning use is still relatively low in the country, rising from 10 percent in the early 1990s to 34 percent in 2010. Most women opt for modern contraceptive methods, especially injectable hormones and oral contraceptives. Family planning use is much higher among more-educated women. One-half of married women ages 15 to 49 with at least some secondary education were using a contraceptive method at the time of the DHS, compared with just 22 percent of similar women with no education (see figure). Similarly, contraceptive use is higher in urban areas (45 percent) than in rural areas (30 percent).

Percent of Married Women Using a Contraceptive Method by Education in Tanzania, 2010

Source: Tanzania Bureau of Statistics and ICF Macro, Tanzania 2010 Demographic and Health Survey: Preliminary Report (Calverton, MD: ICF Macro, 2010).

Family Planning to Reduce Maternal and Child Mortality

Increased family planning use can also help reduce Tanzania’s high maternal mortality. Research has demonstrated that family planning can prevent up to one in every three maternal deaths by allowing women to avoid high-risk pregnancies and abortion of unintended pregnancies.4 When women can wait at least two years between pregnancies, their children are healthier, reducing infant and child mortality. The 2010 DHS indicates continued increase in the use of effective contraceptive methods, which can help Tanzania improve the health of mothers and children and ease the burden of widespread poverty.

Mary Mederios Kent is a senior demographic writer at the Population Reference Bureau.

References

- Population Reference Bureau, DataFinder: Tanzania, accessed at www.prb.org/Datafinder.aspx, on Nov. 10, 2010; and United Nations Population Fund and Population Reference Bureau, Country Profiles for Population and Reproductive Health: Policy Developments and Indicators: 2009/2010 (Tanzania), accessed at www.prb.orghttps://www.prb.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/unfpacountryprofiles.pdf, on Nov. 10, 2010.

- Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics and ICF Macro, Tanzania 2010 Demographic and Health Survey: Preliminary Report (Calverton, MD: ICF Macro, 2010); and Tanzania Bureau of Statistics and Macro International, Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 1996 (Calverton, MD: Bureau of Statistics and Macro International, 1997).

- World Health Organization (WHO) et al., Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2008 (Geneva: WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and The World Bank, 2010), accessed at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241500265_eng.pdf, on Nov. 10, 2010.

- Rhonda Smith et al., Family Planning Saves Lives, 4th ed. (Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau, 2009).

Progress Against HIV/AIDS Amidst Persistent Challenges

(December 2010) A new report from the international organization UNAIDS has good news about progress in fighting the global HIV/AIDS epidemic. Although the number of people living with HIV remains high—33.3 million in 2009—fewer people are becoming infected with HIV. Four decades into the seemingly intractable epidemic, UNAIDS reports that “the world has turned the corner—it has halted and begun to reverse the spread of HIV.”1 Since peaking at about 3.2 million in 1997, the number of new annual infections has fallen 19 percent to 2.6 million. The number of AIDS-related deaths fell from a peak of 2.1 million in 2004 to an estimated 1.8 million in 2009.

In all but a few world regions, the prevalence of HIV/AIDS has declined. In sub-Saharan Africa, where more than two-thirds of the world’s HIV-positive people live, the percent of adults living with HIV fell from 5.9 percent in 2001 to 5.0 percent in 2009. Prevalence also slipped slightly in South/Southeast Asia and in East Asia, as well as the Caribbean. In contrast to the general trend, the HIV prevalence rate rose a bit in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Five countries in this region (Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan) saw the incidence of new cases increase more than 25 percent between 2001 and 2009.

Although far from the ultimate goal of preventing any new infections and protecting the rights and well-being of those with HIV, this progress, especially in Africa, suggests that the multifaceted approach to fighting the epidemic has made a difference. The international response includes a wide range of prevention efforts, including educating the public about the risks of unsafe sex; encouraging sexually active people to get tested for HIV; counseling those who test positive for the virus; reducing the stigma and discrimination associated with HIV infection; making the blood supply HIV-free; and widely distributing condoms. In addition, antiretroviral therapy became available for millions of people with HIV in low-income countries in recent years, reducing HIV-related deaths. Transmission of HIV from mother to infant was significantly reduced by the timely administration of antiretroviral therapy for HIV-positive women and their newborn babies.

Declines in New Infections in Major AIDS Countries

The combination of prevention and treatment efforts—along with the natural cycle of epidemics—contributed to significant declines in new infections in some of the world’s major AIDS countries, including Botswana, South Africa, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe. South Africa, the country with the largest number of people living with HIV/AIDS, saw the rate of new infections cut in half between 2001 and 2009. For some countries, the improvement was significant for men and not women, or vice versa, revealing that this progress was not shared equally and underscoring the work still to be done.

HIV and AIDS Indicators in Selected World Regions, 2009

| Adults and Children Living With HIV | New HIV Infections | Percent of Adults Infected With HIV (ages 15-49) | AIDS-Related Deaths | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| World | 33.3 million | 2.6 million | 0.8 | 1.8 million |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 22.5 million | 1.8 million | 5 | 1.3 million |

| South/Southeast Asia | 4.1 million | 270,000 | 0.3 | 260,000 |

| Central/South America | 1.4 million | 92,000 | 0.5 | 58,000 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | 1.4 million | 130,000 | 0.8 | 76,000 |

| North America | 1.5 million | 70,000 | 0.5 | 26,000 |

Note: Limited to regions with 1 million or more people living with HIV.

Source: Joint United National Programme on HIV/AIDS, UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2010 (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2010).

More Practice Safe Sex

The decline in new infections among young people in several African countries show that more people are practicing safer sexual behavior, in what UNAIDS calls a “revolution in HIV prevention.” Several national surveys in high-HIV African countries indicate that teenagers are waiting longer to have sex, and that sexually active adults have fewer sexual partners and are more likely to use condoms. In Zimbabwe, for example, surveys show that men are now less likely to have casual sex partners than in the past. These are welcome findings because HIV prevention requires people to change their sexual behavior—which often means modifying well-established patterns.

Expanded Treatment Reduces Deaths

In the past decade, the international response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in less developed countries expanded to include antiretroviral therapy. These medicines do not cure the disease, but had been used successfully in wealthier countries to slow the progression of the disease and allow those with HIV to live longer and more active lives. Although many public health experts were skeptical that this therapy could be successfully used in poor countries with limited health infrastructures, UNAIDS reports that expanding access to treatment contributed to a 19 percent decline in deaths among people living with HIV/AIDS between 2004 and 2009.

By 2009, an estimated 5.5 million people were receiving antiretroviral therapy; another 10 million were eligible for treatment but not receiving it. The international community hopes to expand the reach and success of treatment with the introduction of a new approach which could avert an additional 10 million AIDS-related deaths by 2025, compared with current treatment approaches.

Continuing Challenges

The good news about progress against HIV/AIDS is tempered by the magnitude of the existing problems: More than 30 million people live with an incurable disease that is transmitted primarily through sexual contact and injecting drug use. The epidemic has had a devastating effect on the economic and social lives of tens of millions of families, especially in southern and eastern Africa. More than 2 million more people are infected with the virus each year. But the mounting evidence of successful approaches to stopping the spread of HIV, even in the poorest countries, offers hope.

Reducing HIV infection and improving the lives of people living with HIV required extensive national and international resources and political commitment. These resources and commitments will need to continue, even in a time of economic downturn, to halt the epidemic.

Mary Mederios Kent is senior demographic writer at the Population Reference Bureau.

References

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2010 (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2010), accessed at www.unaids.org/GlobalReport/default.htm, on Dec. 1, 2010.

Shifting Latino Ethnic and Racial Identity

Date

December 27, 2010

Author

PRB

(December 2010) Over the past several decades, the U.S. Census Bureau has used variations in its attempt to classify and enumerate Latinos. The 1930 Census was the first time that the bureau attempted to identify and count Latinos specifically. At that time, at the height of the mass movement of Mexicans to the United States in the period surrounding the Mexican Revolution and the Great Depression, the bureau designated “Mexican” as a racial category. Approximately 1.4 million people were enumerated as Mexican during the 1930 Census.1 Most Mexicans lived in Texas (683,681) or California (368,013). With the onset of the Depression, between 400,000 and 500,000 persons of Mexican origin were repatriated to Mexico.2

As the Latino population increased and with the advent of the Civil Rights era, efforts were made to provide a label to Latinos as a way to facilitate their enumeration. Prior to the 1970 census, the labels of “persons of Spanish surname” or “persons of Spanish language” were used to count the population based on the region of the United States. As the 1970 Census neared, the U.S. Interagency Committee on Mexican American Affairs pressured President Nixon to include an item on the census to count Latinos.3 Although the request came too late for the Hispanic item to be included in the short-form questionnaire, it was included in the 5 percent sample long-form questionnaire.

Seven years later, on May 12, 1977, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) ordered that there would be two ethnic categories for data collection purposes: Hispanic and non-Hispanic.4 According to the OMB, Hispanics included people from Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central or South American, or other Spanish culture or origin.5 While the term “Hispanic” became official, there was much debate within the Hispanic and Latino community over the proper term to identify this population. Opponents of the Hispanic term claimed that the term emphasized the Spanish element while neglecting the group’s indigenous roots centered in Latin America. Opponents of the Latino term declared that the term ignores the Spanish roots and excludes people originating from Spain. Today both terms are accepted even though there is often an underlying tension. Nonetheless, a Pew Hispanic Center survey conducted in 2008 indicated that while 43 percent of respondents did not have a preference concerning the two terms, 36 percent preferred the Hispanic identity while 21 percent opted for the Latino label.6

Since Hispanics or Latinos are considered an ethnic and not a racial group, they are asked on census questionnaires to select a racial category. In the 2000 Census, almost half (48 percent) of Latinos classified themselves racially as “white” while more than two-fifths (43 percent) identified themselves racially as “Other.”7 The significance of the high percentage that claims that they identify with the “Other” racial category—rather than the “white” classification—is not completely understood. Possibilities include that such persons view Hispanic or Latino as a racial category and do not locate it among the list of choices, while others may use the term as a rejection of white racial identification, and others may be confused about the racial categories.

The Census Bureau has attempted to provide greater clarification in the annual American Community Survey (ACS) and in the 2010 Census in its attempt to move people away from the “Other” racial designation. The questionnaire emphasizes that “Hispanic origins are not races.” In addition, the layout of racial categories is different from the 2000 Census questionnaire.

Such changes in the census questionnaire appear to have changed the way Latinos identify themselves racially. For example, the percentage of Latinos selecting the white racial category increased from 48 percent in the 2000 Census to 63 percent in the 2009 ACS.8 In contrast, the percentage of Latinos preferring the “Other” racial category dropped from 43 percent to 29 percent. This trend is consistent across Latino subgroups. Cubans have the strongest preference for the white racial category (88 percent). Dominicans have the weakest preference for this racial category (35 percent), opting instead for the “Other” racial category (49 percent).

Rogelio Saenz is professor of sociology at Texas A&M University.

References

- Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung, “Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1970, and By Hispanic Origin, 1790 to 1990, For the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States,” Working Paper Series 56, accessed at www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0056/tabE-07.pdf, on Nov. 28, 2010.

- Robert R. McKay, “Mexican Americans and Repatriation,” The Handbook of Texas Online, accessed at www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/pqmyk, on Nov. 28, 2010.

- Harvey M. Choldin, “Statistics and Politics: The ‘Hispanic Issue’ in the 1980 Census,” Demography 23, no. 3 (1986): 403-18.

- C. Matthew Snipp, “Racial Measurement in the American Census: Past Practices and Implications for the Future,” Annual Review of Sociology 29 (2003): 563-88.

- Office of Management and Budget, Directive No. 15, Race and Ethnic Standards for Federal Statistics and Administration Reporting (Washington, DC: Office of Management and Budget, 1977).

- Jeffrey Passel and Paul Taylor, Who’s Hispanic, accessed at http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/111.pdf, on Nov. 28, 2010.

- Rogelio Saenz, Latinos and the Changing Face of America (New York: Russell Sage Foundation; Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau, 2004).

- Saenz, Latinos and the Changing Face of America; and author’s estimates using the 2009 1% American Community Survey.