Mark Mather

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

December 22, 2015

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

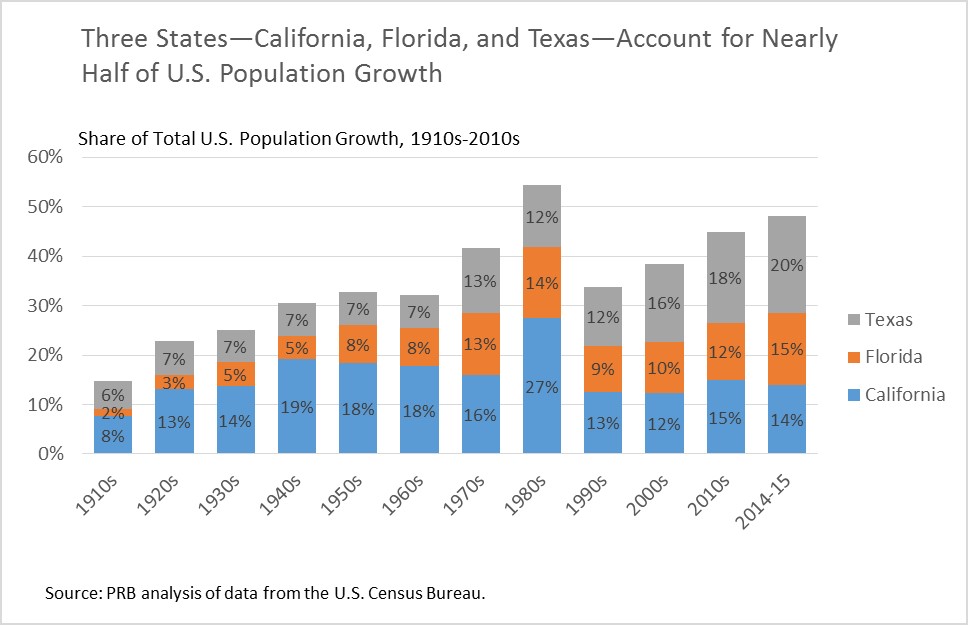

California, Florida, and Texas made up a combined 27 percent of the U.S. population in 2015 but accounted for 48 percent of U.S. population growth between 2014 and 2015, according to new Census Bureau estimates. The relatively fast growth in these three states reflects a combination of factors, including a rebounding economy that has fueled domestic and international migration in many Sun Belt states; and rapid population growth among first- and second-generation immigrants, especially from Latin America. If current trends continue, the combined population in California, Florida, and Texas could exceed 100 million people by 2030—up from 81 million in 2010—as the three states increase their economic and political positions relative to the rest of the country.1

The recent population growth in California, Florida, and Texas represents a sharp increase compared with the 2000s (when the three states made up 38 percent of total growth) and the 1990s (when they accounted for just 34 percent of growth) (see figure). The 1980s was the only decade in which the three states accounted for a greater share of total growth (54 percent), owing mostly to rapid population growth in California during that decade. Since 2010, Texas has had the largest net increase in population among the 50 states—adding 2.3 million people, more than the net population increase in all of the states in the Northeast and Midwest combined (1.9 million).

Since 2010, the percent increase in population in Texas (9.2 percent) was more than double the population growth rate in the United States as a whole (4.1 percent). Population growth in Florida (7.8 percent) and California (5.1 percent) was more modest but was still associated with large numerical gains because of the large populations in those states.

One hundred years ago, 60 percent of the U.S. population lived in the Northeast and Midwest. Populations in California, Florida, and Texas were increasing rapidly but made up just 8 percent of the total U.S. population. During the course of the 20th Century, as the U.S. population shifted to the South and West, California, Florida, and Texas accounted for a growing share of overall population change. This growth expanded rapidly in the 1980s as California attracted a large number of domestic and international migrants.

All three states continued to grow during the 1990s but trends in California, Florida, and Texas were overshadowed by rapid growth in the Mountain West, especially in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, and Utah. During the 2000s, the housing market crisis and recession dampened population growth in California and Florida, while the population in Texas—which was somewhat insulated from the economic downturn—continued to increase rapidly.

Since 2010, migration flows to the Sunbelt have rebounded, although they have not returned to their peak levels from the mid-2000s. Just last year, in a major shift in the demographic balance, Florida passed New York as the third most-populous state. Improvements in the housing and job markets may help explain Florida’s rebound. At 5 percent, the national unemployment rate is down sharply from its double-digit peak of more than 10 percent in October 2009, and fewer homeowners have mortgages that are “under water.” As of November 2015, the unemployment rates in Texas (4.6 percent) and Florida (5.0 percent) were at or below the national average (5.0 percent) while California’s rate remained relatively high at 5.7 percent.

Another key factor driving population growth in California and Texas is their relatively young populations relative to many other states. Having a young population creates population momentum through a large number of births relative to deaths. Between 2014 and 2015, California and Texas registered more than twice as many combined births (902,000) as deaths (443,000), resulting in the addition of 459,000 people through natural increase. Florida also experienced growth due to natural increase during this period, but because of its large population of retirees, had a more balanced mix of births relative to deaths.

The key to the relatively youthful populations in California and Texas—and to a lesser degree, Florida—is immigration, especially from Latin America. While the U.S. population as a whole is aging rapidly as the large cohort of baby boomers reaches retirement age, some states have become “fountains of youth” by attracting immigrant workers—many of whom start families after they arrive in the United States. Between 2014 and 2015, California, Florida, and Texas had a net (combined) increase of 412,000 international migrants, mostly from Latin America. California had the largest net increase in international migrants among the 50 states, followed by New York, Florida, and Texas.

Domestic (state-to-state) migration was another key factor driving population growth in Florida and Texas between 2014 and 2015. Young adults are moving to these states primarily for jobs, while many older adults move to the Sun Belt to escape the cold northern winters, to live closer to family members, or for the lower cost of living. During the same period, California experienced a net outflow of domestic migrants, as many residents moved to lower-cost states, especially Arizona, Nevada, and Texas.

State population gains and losses are important not only from a demographic and economic perspective, but also because they affect the balance of political power in Congress. After each decennial census, population totals in each state are used to reallocate the 435 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Over the past century, southern and western states have gained seats at the expense of states in the Northeast and Midwest, and this trend is continuing. Texas gained four seats during the reapportionment process following the 2010 Census, while Florida gained two. In the current Congress, California leads the nation with 53 seats, followed by Texas (36), and Florida and New York (27 each).

If current trends continue, California and Florida could each gain another congressional seat after the 2020 Census, and Texas could gain another three seats.2 Although it’s difficult to predict longer-term trends, state demographers in California, Florida, and Texas expect that these population gains will continue at least through 2030, when the combined population of the three states could reach 100 million people.

December 21, 2015

(December 2015) Senegalese journalist Maimouna Gueye won a 2015 Global Health Reporting award from the International Center for Journalists for stories she wrote after participating in a program organized by the Population Reference Bureau (PRB) in southern Senegal and the capital, Dakar.

Maimouna at a clinic interviewing women who had returned with their babies (humanized childbirth).

Her stories focused on high rates of teen pregnancy in the Ziguinchor region of southern Senegal, a “freestyle” method of natural childbirth, and reproductive health care among migrants in informal settlements in central Dakar. Gueye is the editor-in-chief of Senegal’s national daily, Le Soleil, and coordinates the newspaper’s health section.

She was among more than 150 journalists who submitted stories for the 2015 Global Health Reporting Contest. Six winners were selected and honored at an awards dinner in New York on Dec. 7.

Gueye was among six journalists from Dakar and five from southern Senegal who participated in a PRB study tour in the Ziguinchor region in March/April 2015. This region was chosen because of its high rate of teenage pregnancies and low use of contraceptives. It has among the worst health indicators in the country, due partly to its distance from Dakar, and because until recently it was the center of a secessionist movement that led to years of violent conflict with the Senegalese military.

The Dakar migrant community.

The journalists met with officials from the Health and Education ministries and visited youth centers and schools. They were most energized when they talked to young people—ranging from students in one-room schoolhouses to out-of-school youth driving motorcycle taxis. Perhaps the most moving stories, though, came from their interviews with young women living in an urban slum located close to a military barracks. As Gueye described in her story, the majority of these women already had one or two children, often fathered by soldiers stationed in the nearby camp, and saw little hope for the future.

Another of Gueye’s winning stories evolved from a site visit during a four-day workshop in May 2014 that PRB organized for journalists from the nine countries in the Ouagadougou Partnership (OP), a regional initiative aimed at increasing use of family planning. Twenty journalists participated in the workshop focused on their countries’ OP commitments to increase access to contraception. The program included presentations as well as site visits. One that most interested the journalists was to a newly renovated clinic using the concepts of natural childbirth to improve maternal and infant health.

The clinic is a project of Senegal’s Ministry of Health and the Japanese government and uses the term “humanized childbirth” to describe the various alternatives it provides to women for “freestyle” deliveries. Rather than having no option other than lying on a delivery table and having limited movement, the clinic was configured to enable women to be in whatever position they choose when they deliver their babies, whether standing, sitting, squatting, or lying on a mattress.

Gueye’s third story resulted from a December 2013 PRB workshop that focused on the lack of family planning services for migrants and others in the low-income neighborhoods of the Senegalese capital, called Dakar Plateau. It is a busy, downtown residential area for the very rich, who live in the old colonial neighborhoods, and the very poor, who live in shacks and tents in the hidden areas behind the main streets, between buildings, and around the bus and train stations. Among the poor, unmet need for contraception is high.

During the one-and-a-half-day workshop, six journalists heard presentations from Dakar health workers, interviewed the mayor of Dakar Plateau, and visited health centers and neighborhoods where migrants live, often without electricity or running water. In her article, Gueye described the health challenges residents face, especially the deeply conservative Muslim migrants from Guinea who account for 90 percent of the births at a local health center. Most do not use family planning because they think it is only for preventing pregnancy permanently; many are unaware that it is also a way to space births two or more years apart to ensure healthier babies and protect the health of older siblings.

December 16, 2015

Former Program Director

Principal Researcher at the Ethiopian Economics Association (EEA)

(This article was originally posted on the New Security Beat, the blog of the Environmental Change and Security Program.)

(December 2015) Inspired by the success of East Asian economies, the demographic dividend framework is taking off in sub-Saharan Africa, where many are yearning for workable solutions to the region’s ongoing development challenges.

In Addis Ababa this week during a workshop hosted by the National Planning Commission and the United Nations Population Fund, leaders will grapple with how to accomplish the economic boost of a demographic dividend in Ethiopia. As a climate change hotspot facing one of its worst droughts in decades, the linkages between Ethiopia’s population and its development are more important than ever.

A demographic dividend refers to accelerated economic growth that can begin when a country shifts from high to low birth and death rates. As mortality and fertility decline, a country’s working-age population grows in relation to the number of young dependents, opening a window of opportunity for faster economic growth.

Over the last two decades, Ethiopia has experienced an impressive decline in fertility, enjoyed strong economic growth, and made great strides in poverty reduction. According to a new report, these achievements indicate that Ethiopia may be on track to reap a demographic dividend, but policymakers must act to both take advantage of opportunities and address remaining challenges.

Read the rest of this post on the New Security Beat.

Assefa Admassie is a principal researcher at the Ethiopian Economics Association. Shelley Megquier is a policy analyst at the Population Reference Bureau.

In the United States, full-time working women earn less than men, on average—even in female-dominated occupations (those in which women comprise 70 percent or more of workers), such as nurse practitioners, office clerks, and flight attendants. There are no occupations in which women’s median annual earnings are significantly higher than men’s. Using the latest and most detailed data available, the graphic below shows more than 50 occupations with the biggest gaps in pay parity, where full-time working women earn 75 cents or less, on average, for every dollar made by men in the same job.

December 9, 2015

(December 2015) In late November, Nigerian parliamentarian Babatunde Gabriel Kolawole spoke in the National Assembly and implored his colleagues to come up with a viable policy to “curb the population explosion in Nigeria.” Already the seventh-largest country by population in the world, Nigeria is on track to be the fourth-largest in 2050, with nearly as big a population as the United States. Nigeria’s total fertility rate is a high 5.5 children per woman.1

According to news reports, Kolawole backed a proposed motion for population policy legislation with projections from PRB’s World Population Data Sheet as evidence of a brewing crisis and the need to take quick policy action to avert it.2

This was a timely example of the relevance of the Population Reference Bureau (PRB)’s work to provide practical, evidence-based knowledge of family planning and other critical policy issues that affect the well-being of current and future generations, both globally and in the United States. The event also highlighted the politically charged nature of family planning discussions in Nigeria. According to the reports, some members of the National Assembly saw Kolawole’s motion as a potential threat to the country’s Muslims, who reside mainly in northern Nigeria and make up roughly half of the country’s population.3 The reports cited Zakara Mohammed, another parliamentarian, as saying that in Islam and in northern Nigeria generally, having more than one wife and bearing as many children as one likes is acceptable practice.

In a subsequent interview with the National Mirror, Kowawole sought to clarify his position. He expressed his surprise that the motion was viewed as an attack on Muslims. “That was not the intention of the motion. The motion was simply asking that the federal government should take steps to manage the population, and…educate Nigerians on the benefit of family planning,” he said. He also emphasized that an “…unbridled and unmanageable population has negative consequences. Everyone knows that. If at an estimated 166 million we are still adding about 5 million births per annum, there should be cause to worry.”

The parliamentary exchange comes in the context of diverging population trends among Muslims and non-Muslims in Nigeria (see Table). In 1990, Muslim women of childbearing ages (15 to 49) had on average 6.5 births, compared to 5.6 for non-Muslim women (the latter are mostly Christians, but also a small percent of people practicing traditional religions). By 2013, non-Muslim fertility had fallen to 4.5 births, while Muslim fertility remained the same, leading to a two-child difference between Muslims and non-Muslims, according to a recent report by Princeton’s Charles Westoff and PRB’s Kristin Bietsch, published by the Demographic and Health Surveys.5 This difference in fertility will lead to faster population growth among Muslims than non-Muslims in Nigeria.

Table

Fertility Trends Among Muslim vs. Non-Muslim Women in Nigeria

| Muslim | Non-Muslim | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Fertility Rate (TFR) (1990)* | 6.5 | 5.6 |

| TFR (2013) | 6.5 | 4.5 |

| Age at First Marriage (years) | 16 | 21 |

| Never Attended School (%) | 65 | 9 |

| Use of Contraception (any method) (%) | 6 | 29 |

| Desire to Stop Childbearing (%) | 11 | 31 |

*Note: All data except for 1990 TFR are from 2013.

Source: Adapted from Charles F. Westoff and Kristin Bietsch, “Religion and Reproductive Behavior in Sub-Saharan Africa,” DHS Analytical Studies No. 48 (Rockville, MD: ICF International, 2015), accessed at www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/AS48/AS48.pdf, on Dec. 9, 2015.

Muslims girls and women tend to marry much younger than their Christian counterparts: The average age at first marriage is 16 for Muslim women, compared to 21 for non-Muslims.6 Also, 44 percent of married Muslim women are in polygynous unions, compared to 17 percent of non-Muslim wives.7 The differences in age at marriage also lead to differences in educational attainment for women: While only 9 percent of non-Muslim women in Nigeria have never attended school, the share is 65 percent for Muslim women.8

Only 6 percent of married Muslim women are currently using any form of contraception, compared to 29 percent of married, non-Muslim women.9 If family planning were widely available, fertility would not decline much among Muslims. On average, Muslim women in Nigeria wish to have more than eight children each, and also express less desire to halt childbearing: Three times as many non-Muslims wish to have no more children compared to Muslims (31 percent compared to 11 percent, respectively).10

Even when accounting for the socioeconomic differences between Muslims and non-Muslims in the country, the report finds that Nigerian Muslims are more likely to marry younger, to desire larger families, and to never have used contraception.

Note that this is not intended as a condemnation of reproductive preferences or practices of Muslims or any other group in Nigeria. Population growth rates should also not be forcibly changed and people’s rights should be respected. Rather, as Kolawale is cited as saying, the focus should be on public education about and availability of family planning options to help people decide when and how many children to have.

Product: Infographic

Author: PRB

Date: December 7, 2015

December 7, 2015

On Dec. 8, 2015, the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program is hosted a full day event that explored how countries can achieve a demographic dividend through empowerment, education, and employment for youth.

Investments in young people are crucial to achieving a demographic dividend. The demographic dividend provides a framework for promoting investments in youth as fertility declines and population age structure changes. Sustained investments in voluntary family planning, health, education, and job growth can help to guide a country towards a demographic dividend.

Some related PRB materials include:

December 4, 2015

(December 2015) With the signing of the Iranian Nuclear Deal and subsequent easing of economic sanctions, new opportunities will arise for Iranian workers to compete in the global market. Due to high fertility rates in the recent past, Iran has a large working-age population that stands to perfectly capitalize on these developments, allowing the country reap its demographic dividend. Iran cannot afford to miss this window of opportunity.

Read the entire article in the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs.

December 2, 2015

Former Associate Vice President

(December 2015) As the world turns its attention to Paris and the global climate talks, decisionmakers are increasingly making the connection between population and climate change. Research is expanding on the contribution of population size, growth, and composition to climate change.

Experts are also showing the connection between these population dynamics and vulnerability and resilience to the impacts of climate change. The topic, however, remains challenging and at times controversial for many policy advocates. Some argue that linking population growth, particularly family planning, to climate change is the same as blaming parents of large families in developing countries for the climate changes that are caused by smaller high-consuming families in developed countries.

The relationships are far more complex. Over the last two years, the Population Reference Bureau (PRB) has worked with scientists and policy experts to explore these connections and create spaces for thoughtful discussion of policy opportunities. We have found innovative ways to communicate the complexity of the connections through interactive graphics, policy briefs, and reports, interviews with the media, and events with policymakers and climate negotiators. Through this careful and evidence-based work, we have learned that we can make the link, remove the controversy, and constructively contribute the word “population” to climate talks.

December 1, 2015

Former Program Director

This article was originally posted on the Ms. Magazine blog.

In the mid-1990s, I served as a Peace Corps volunteer in a village in Niger, a West African country consistently ranked as one of the poorest in the world. I lived in a mud hut, learned a local language, made lasting friendships and did interesting work. Nearly 20 years later, two memories stand out from those years: It was incessantly hot, and I went to a lot of baptisms.

Things haven’t changed much in Niger since then, except that women are having even more children and it’s getting even hotter and drier. Niger’s fertility rate, historically very high, is now the world’s highest at an average of 7.6 children per woman (compared to 1.9 in the United States). Niger had about 9 million people in 1996 and now there are almost 19 million.

By 2050, Niger’s population is projected to more than triple to 68 million unless the birth rate slows substantially. But currently only 12 percent of married women in Niger use a modern form of contraception, compared to an average of 29 percent across Africa and 56 percent globally. There is an urgent need to make voluntary contraception available so that women and their families are able to live healthy, productive lives.

Early marriages also play a key role in birth rates by extending the length of childbearing years, and they pose high health risks for women. In Niger, half of girls are married before their 16th birthday. I saw this up close when I lived there. Salama, a young bride who was pregnant for the first time, lived on the edge of the village in an impeccably clean house. I used to go and talk with her when I needed a quiet escape from the bustle of village life. Like many Nigerien women wed too young, she died during childbirth from laboring too long to deliver a baby too large for her still developing adolescent body. In fact, Save the Children rated Niger the worst place in the world to be a mother.

Meanwhile, Niger is acutely vulnerable to climate change. It’s a large country, about twice the size of Texas, but only about 13 percent of the country is suitable for agriculture, and even that land is dry for much of the year. Much of the country is part of the Sahara Desert. Families are having a harder time each year eking out enough food from this parched land, and it’s difficult to provide enough pasture and water for their livestock, too.

These twin challenges for Niger (and many other nations) will come into focus later this month when countries from around the world gather in Paris for a major conference on climate change. It’s an occasion for the world’s leaders to commit to real action to slow global carbon emissions that heat the planet and exacerbate the kinds of challenges Nigeriens face.

How does family planning fit into the climate change picture? Research supports the linkage by showing that fewer people in the world could lead to substantial long-term climate-related benefits by lowering carbon emissions. Approximately 222 million women in the world would like to plan the number and spacing of their children, but currently are not able to because they don’t have access to modern contraception. Meeting their needs through providing voluntary, rights-based family planning could be a global hat trick–for women, their children and the climate. And for women and their households, the additional health, education and economic benefits that accompany family planning would reduce their vulnerability to the impacts of climate change and build their resilience.

Recently, more scientists and governments have made the connection between population growth and global carbon emissions and have recognized the multiple benefits that family planning provides. Some environmentalists believe there is a strong chance for real progress at the Paris climate talks. My hope is that additional headway will be realized through climate negotiations that acknowledge the compound benefits of rights-based voluntary family planning for women and children at the individual level and for the planet. And in the end, people in Niger and elsewhere will benefit.