Education in the U.S.: The Great Equalizer?

Product: Population Bulletin, vol. 69, no. 2: The Demography of Inequality in the United States

Authors: Mark Mather Beth Jarosz

Date: November 17, 2014

Changes in racial/ethnic composition, immigration, family composition, and age structure are linked to rising income inequality but they are not the primary or root causes. Increasingly, education separates those at the top from those at the bottom.

During the past several decades, incomes have risen rapidly at the top of the income distribution, driven by technological changes combined with a slowdown in the supply of highly educated workers that has increased the returns to education.37 At the same time, structural changes in the U.S. economy have reduced real income for those with less education and fewer skills. Higher-paid manufacturing jobs have been replaced by lower-paid service jobs, resulting in stagnant or declining wages for those without college degrees.38 The recession exacerbated this trend by disproportionately affecting less-educated workers.39

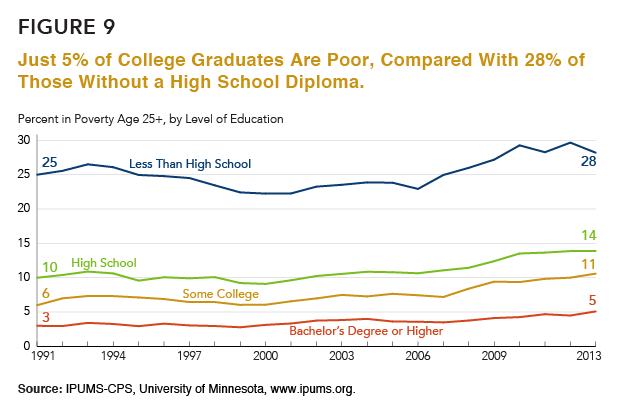

A persistent economic gap exists between college graduates and those without college degrees (see Figure 9). The poverty rate for adults ages 25 and older without a high school diploma fell slightly in 2013, but at 28 percent, is still double the poverty rate among high school graduates (14 percent). Just 5 percent of college graduates were poor in 2013.

In the United States, more than six out of every 10 jobs require some postsecondary education and training.40 Although there are many jobs that do not require college degrees, with increasing globalization in a knowledge-based economy, the demand for highly educated and skilled workers in the United States will only continue to grow. For most young people, going to college is one of the most important steps they can take to become financially independent adults. College graduates have significantly higher lifetime earnings ($2.3 million) compared with those who have no education beyond high school ($1.3 million).41 College graduates are also much less likely to be unemployed and they enjoy a wide range of other social, economic, and health benefits.42 Parents who have completed college are also much more likely to have children who go to college, so the benefits of education are transferred from one generation to the next. Increasing college completion rates also boosts potential innovation, economic output, and productivity.43

In recent years, college enrollment and “persistence” rates have declined, and some policymakers and others are concerned that future generations of young adults may have less education than their parents and grandparents—a trend that could undermine economic growth and exacerbate levels of income inequality in the United States.

Recent estimates suggest that demand for college-educated workers has outstripped supply since the early 1990s, and some experts warn that educational progress could stall in the coming decades. Slower gains in college enrollment and completion are projected with the changing racial/ethnic composition of the U.S. population. A growing share of young adults are Latino, including many first- and second-generation immigrants who are less likely to graduate from high school or college compared with those in U.S.-born families. Among young adults ages 25 to 29, Latinos are the least likely to finish four years of college (16 percent), while college completion rates are highest among Asian Americans (59 percent) and whites (40 percent).44 With the Latino population projected to continue its rapid growth, the deficit in college-educated workers may increase unless these gaps are reduced.

Lower-income families often struggle to cover the costs of education for their children, especially at the college level. Students in low-income families are more likely to be enrolled in community colleges, with fewer resources and less institutional support than students from more-affluent families. One study showed that the college completion rate for students starting at community colleges is only 18 percent, compared with a 90-percent completion rate among students at selective private colleges and universities.45

Investing in Education

Investments in education are key to reducing disparities between population groups. From preschool through college, education provides necessary stepping stones for success later in life. For young children, attending preschool prior to kindergarten leads to better cognitive outcomes, social skills, and school achievement.46 Finishing high school puts children on the path to becoming productive adults. Many teen dropouts are disconnected from both school and the workforce, and they are twice as likely to be poor as their peers who are in school or working. A college degree generally leads to a good job, higher earnings, and upward mobility.

Education is also a key predictor of health and longevity.People with higher levels of education have higher earnings; live in better neighborhoods; and can afford to buy better medical care, health insurance, and healthier foods.47

In the coming decades, college completion rates will most likely continue to increase, although at a slower pace than policymakers and education advocates would like. The White House has set an ambitious goal of increasing the share of U.S. adults ages 25 to 34 with college degrees from roughly 40 percent today to 60 percent by 2020.48 However, the National Center for Education Statistics projects that the United States will fall well short of this goal.49

Policymakers can take steps to boost educational attainment by increasing tuition assistance to lower-income families, so that children growing up in these families have the same access to college as those in higher-income families; reaching out to potential college students living in remote or underserved communities, especially those in high-poverty urban and rural areas; providing child care, housing, and transportation assistance to lower-income families, so that parents can reach their own educational and occupational goals—and then pass those same aspirations and expectations on to their children; and ensuring that children in middle and high school are academically prepared for college, to create a stronger education pipeline.

NEXT: Looking Ahead

POPULATION BULLETIN CHAPTERS

Introduction

The Backdrop: Rising Inequality

Where Poverty and Inequality Intersect

The Generational Divide

Persistent Racial/Ethnic Gaps

Women Making Progress, But Gaps Remain

Education: The Great Equalizer?

Looking Ahead

References

- Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz, The Race Between Education and Technology (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009).

- Pew Research Center, “The Rising Cost of Not Going to College,” accessed at www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/02/11/the-rising-cost-of-not-going-to-college/, on Aug. 5, 2014.

- Kristie Engemann and Howard Wall, “The Effects of Recessions Across Demographic Groups,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2009-052A (2009).

- Anthony P. Carnevale, Nicole Smith, and Jeff Strohl, Recovery: Job Growth and Education Requirements Through 2020 (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, 2013).

- Anthony P. Carnevale, Stephen J. Rose, and Ban Cheah, The College Payoff: Education, Occupations, Lifetime Earnings (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, 2011).

- Sandy Baum, Jennifer Ma, and Kathleen Payea, Education Pays 2013: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society (New York: College Board, 2013).

- National Center for Education Statistics, Education and the Economy: An Indicators Report (Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, 1997).

- U.S. Census Bureau, “CPS Historical Time Series Tables,” accessed at www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/education/data/cps/historical/index.html, on Oct. 20, 2014.

- John Bound and Sarah Turner, “Collegiate Attainment: Understanding Degree Completion,” NBER Reporter 2010, Number 4: Research Summary.

- Gregory Camilli et al., “Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Early Education Interventions on Cognitive and Social Development,” Teachers College Record 112, no. 3 (2010): 579-620.

- Robert A. Hummer and Elaine M. Hernandez, “The Effect of Educational Attainment on Adult Mortality in the United States,” Population Bulletin 68, no. 1 (2013).

- U.S. Department of Education, “Meeting the Nation’s 2020 Goal: State Targets for Increasing the Number and Percentage of College Graduates With Degrees” (March 18, 2011), accessed at www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/completion_state_by_state.pdf, on Oct. 24, 2014.

- National Center for Education Statistics, “Projections of Education Statistics to 2021,” accessed at http://nces.ed.gov/programs/projections/projections2021/, on Oct. 28, 2014.

">

">