Toshiko Kaneda

Technical Director, Demographic Research

(April 2006) Populations in developing countries will be aging rapidly in the coming decades: The number of older persons (those age 65 or older) in less developed countries is expected to increase from 249 million to 690 million between 2000 and 2030.1 And because the elderly are at high risk for disease and disability, this population aging will place urgent demands on developing-country health care systems, most of which are ill-prepared for such demands.

Chronic disease now makes up almost one-half of the world’s burden of disease, creating a double burden of disease when coupled with those infectious diseases that are still the major cause of ill health in developing countries.2 The challenge for developing countries is to reorient health sectors toward managing chronic diseases and the special needs of the elderly. Policymakers must take two steps: Shift health-sector priorities to include a chronic-disease prevention approach; and invest in formal systems of old-age support (see A Critical Window for Policymaking on Population Aging in Developing Countries for more discussion on population aging and the options for old-age support).

More specifically, these countries should institute prevention planning and programming to delay the onset of chronic diseases, enhance care for the chronic diseases that plague elderly populations, and improve the functioning and daily life for the expanding elderly population.

Population aging has been accompanied by an epidemiological shift in the leading causes of death from infectious and acute conditions associated with childhood to chronic conditions. A confluence of factors has spawned this epidemiological transition: modernization and urbanization (especially improvements in standards of living and education); and better nutrition, sanitation, health practices, and medical care.

Projections made by the World Health Organization (WHO) suggest that, by 2015, deaths from chronic diseases—such as cancer, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes—will increase by 17 percent, from 35 million to 41 million.3 But few developing countries have implemented primary prevention programs to encourage those healthy lifestyle choices that would mitigate chronic diseases or delay their onset. Rarely do developing countries have the appropriate medicines or adequate clinical care necessary to treat these diseases.

To encourage a prevention approach, WHO launched in 2002 its Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions Framework (ICCC), aimed at policymakers in the health sector. This framework takes the approach that nonadherence to long-term treatment regimens is fundamentally the failure of health systems to provide appropriate information, support, and ongoing surveillance to reduce the burden of chronic disease. The framework also advises that a prevention approach can mitigate these problems and contribute to healthier lifestyles.4

Delaying the onset of disability through prevention approaches can both alleviate the growing demand for health care and, more important, improve the quality of life for the elderly.

Primary Prevention. A prevention approach can be undertaken even where there are resource constraints and age discrimination. Unfortunately, a “negative aging paradigm” found in both developed and developing countries assumes that older people’s health needs require high-cost, long-term treatments.5

Critics of this paradigm point out that, while the elderly are indeed more likely than younger groups to suffer from chronic diseases, there is still considerable scope to improve their health and quality of life through relatively low-cost interventions. Some chronic conditions—such as heart disease, diabetes, and many cancers—have well-known risk factors that can be affected by lifestyle and behavioral changes that include quitting smoking, improving diet, and increasing physical activity.6

Primary prevention programs such as tobacco education and control are one example of these low-cost interventions. In India, the world’s second-largest producer and consumer of tobacco, cardiovascular disease mortality is projected to account for one-third of all deaths by 2015.7 In response, the Indian government enacted in 2003 a comprehensive national law for tobacco control; it also established a National Tobacco Control Cell within the Health Ministry that encourages state governments to develop tobacco cessation programs in selected health-care facilities.8

These measures resulted in the establishment of 13 smoking cessation centers in settings as diverse as cancer treatment centers, psychiatric units, medical colleges, and nongovernmental organizations. In 2005, the programs expanded to include five new Indian states.9

Secondary Prevention. Whereas primary prevention programs target populations before a disease develops, secondary prevention involves identifying (through screening) and treating those who are at high risk or already have a disease.

Secondary prevention is also necessary to prevent recurrence of the disease. For example, all developing-country health sectors should use aspirin, beta blockers, and statins as mechanisms for secondary prevention of chronic diseases. Incorporating such secondary prevention measures also means providing the technical skills to diagnose and care for patients as well as providing the appropriate medication.

Many countries may not be able to afford these drugs alone, but through the WHO Essential Medicines program, countries can receive guidance on the formularies that meet the standards for a particular drug.10 In China, blood pressure has been shown to decline in individuals involved with community-based hypertension control programs, where activities include weight control, modification of dietary salt and alcohol intake, and increased physical activity.11

Tertiary Care. Once a chronic disease has been diagnosed, tertiary care involves treatment of the disease and attempts to restore the individual to her or his highest functioning. However, WHO reports that adherence to long-term therapy for chronic illnesses is only 50 percent in developed countries, and is likely even lower in developing countries.12 Such poor treatment compliance could be bolstered by cultivating better health awareness through education and outreach programs.

Disability significantly affects quality of life in old age. Types of disability frequently considered among the elderly include limitations in general functioning (such as walking or climbing stairs); managing a home; and personal care. In addition to being consequences of the normal aging process, disabilities are also often caused by chronic diseases. And population aging also increases the prevalence of mental health problems—especially dementia, which results in disability by limiting the ability to live independently. WHO projects that Africa, Asia, and Latin America will have more than 55 million people with senile dementia in 2020.13

Caring for the elderly in a way that addresses disability and maintains good quality of life has become a global challenge. Informal care—often provided by spouses, adult children, and other family members—accounts for most of the care the elderly currently receive in developing countries. Care provided at home is often considered the preference of the elderly and, from a policy standpoint, is essential for managing the cost of long-term care. However, despite the increasing demand for home-based care due to population aging, decreasing fertility rates means that future cohorts of elderly will have smaller networks of potential family caregivers.

The need for public policies to address the demand for caregivers is one of the priority issues for long-term care and a guiding principle for WHO’s 2000 publication Towards and International Consensus on Policy for Long-Term Care of the Ageing.14 In it, WHO urges developing countries to urgently train more professional caregivers to focus on elder care in order to meet current and future demand.

According to WHO, future caregiving for the elderly will also require models of both formal and informal care and systems for supporting caregivers.15 Although formal long-term care programs are vastly underdeveloped in poor countries, they will be essential for complementing the informal support system and sustaining the major role that family caregivers currently play.

Examples of formal long-term care programs that assist informal caregivers include training, respite care, visiting nurse services, and financial assistance to cover care-related expenses. For instance, many East Asian and Southeast Asian countries are providing adult day care and counseling services to help family caregivers.16 Singapore is providing home help, nursing care at home, and priority in housing assignments to family members who were willing to live next door to their older relatives, and Malaysia is offering tax benefits to adult children who live with their parents.

Policies and health promotion programs that prevent chronic diseases and lessen the degree of disability among the elderly have the potential to reduce the impact of population aging on health care costs. Research shows increasing health care costs are attributable not just to population aging but also to inefficiencies in health care systems such as excessively long hospital stays, the number of medical interventions, and the use of high cost technologies.17 Appropriate policies to address health care challenges for aging populations are crucial for developing countries if they are to simultaneously meet the health care needs of their elderly populations and continue their economic development.

For instance, how is a country such as China, the world’s most populous country with one of the fastest aging populations, coping with these issues? What is China doing to address the emergence of chronic disease and population aging? These questions will be explored in-depth in a future article on aging in China.

Toshiko Kaneda is a policy analyst at the Population Reference Bureau.

(April 2003) Reaching age 100 has long fascinated society. The century mark holds an almost mystical importance as a seal of hardiness and good health — the sign of a life well-lived. People who reach 100 are regularly feted in newspaper stories, television broadcasts, and family parties. Some get birthday greetings from the White House. As life expectancy increases, an increasing number of Americans are attaining this milestone.

Centenarians have a unique perspective on our recent history. Americans who reached age 100 in 2000 were born at the dawn of the 20th century. They were too young to participate in World War I and reached adulthood as the world was gripped by the 1918 influenza epidemic. This group was forming its families as the Great Depression started and had some of the highest rates of childlessness recorded in the United States. The advent of World War II found many of them too old to be called into service, but they were a vital force in stateside war efforts. Today’s centenarians reached retirement age as the United States entered the Vietnam War and social turmoil of the 1960s and 1970s. They witnessed remarkable and unprecedented technological and medical advances in their lifetimes.

Centenarians may hold the key to the limits of life and are a new and fascinating focus for medical and social research. Researchers are examining their physical and mental health, their genes, their families, and their lifestyles, trying to unlock the secrets of long life.

The growth in the number of centenarians in the world is remarkable. Accurate records are difficult to come by before the 20th century, although there have been claims of super longevity throughout history, such as the story of 969-year-old Methuselah in the Bible. Other examples of supercentenarian status are found in age claims of 122 years for St. Patrick of Ireland, 152 years for Englishman Thomas Parr (1483-1635), and groups of individuals in Bulgaria, Kashmir, and the Andes. Rigorous investigation of these claims, however, finds no evidence to support them. Some speculate that before 1900 the incidence of centenarians may have been as small as one per century. In small countries, like Denmark, researchers find little evidence of centenarians before the 19th century.1 Given the rarity of living to age 100, it is possible that few populations were large enough until recently to produce any centenarians.

Verification of age is very difficult, even today. Many centenarians do not have birth records or other documents to confirm their stated age. Verification of age entails collecting credible and corroborating evidence from a variety of sources, including interviews with the person when possible. Reported life events are checked for consistency with historical records and documents. Verification becomes more difficult the older the individual and after his or her death.

The oldest known age ever attained was by Jeanne Calment, a Frenchwoman who died in 1997 at the age of 122. Ms. Calment is also the only documented case of a person living past 120, which many scientists had pegged as the upper limit of the human lifespan. In April 2003, the oldest living woman appears to be 115-year-old Kamato Hongo of Japan, born in 1887. The oldest living American woman is Californian Mary Christian, age 113.

| World | United States | |

|---|---|---|

| Oldest Man | Yukichi Chuganji (Japan) | Fred Harold Hale |

| Birth date | March 23, 1889 | Dec. 1, 1890 |

| Age on April 1, 2003 | 114 | 112 |

| Oldest Woman | Kamato Hongo (Japan) | Mary Christian |

| Birth date | Sept. 16, 1887 | June 12, 1889 |

| Age on April 1, 2003 | 115 | 113 |

Source: Gerontology Research Group (www.grg.org, accessed April 2, 2003); and Guinness World Records (www.guinnessworldrecords.com, accessed April 2, 2003).

The oldest documented age for a man is believed to be a Danish immigrant to the United States, Christian Mortensen, who died in 1998 at age 115. One man, Shigechiyo Izumi, is often reported as having reached the age of 120 before his death in 1986 in Japan, but his age has not been verified. Yukichi Chuganji, reaching age 114 in 2003, is believed to be the oldest living man. Maine resident Fred Harold Hall is the oldest living American man — at 112 years of age.

Some 50,000 Americans were reported as centenarians in the 2000 U.S. Census (see figure). Centenarians account for less than 0.2 percent of the 35 million persons age 65 or older, and there is wide agreement that this is an overestimate because of chronic overreporting at the oldest ages.2 Reliable counts for 1990 by the Social Security Administration, for example, put the number of centenarians as closer to 28,000 than the 37,000 reported in the 1990 Census.

Note: Components do not add to total because of rounding.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, PCT3 Sex by Age (http://factfinder.census.gov/, accessed April 2, 2003).

As at all other older ages, women centenarians outnumber men. The 2000 Census recorded four women for every man age 100 or older. Detailed information on centenarians from the 1990 Census reveal that their racial composition is similar to that for all older Americans — 78 percent of centenarians were non-Hispanic white and 16 percent were black. But centenarians have lower levels of education than other elderly Americans, which is not surprising for Americans born before 1900. And women age 100 or older are more likely than men to be widowed. Only about 4 percent of female centenarians counted in 1990 were currently married, compared with nearly 25 percent of the men age 100 or older.

Centenarians are not necessarily in poor health or suffering from chronic disabilities. About 20 percent of the centenarians in the 1990 Census reported no disabilities, although they reported considerably more health problems than people in their 80s.3

What accounts for extreme longevity? It is likely that a combination of genetics, lifestyle, and luck4 are responsible for a long life. As public health measures advanced early in the 20th century, cleaner water, vaccination campaigns, and better personal hygiene allowed more people to live to older ages. More recently, treatments for heart disease, cancer, and other chronic diseases have extended life at the upper extremes. A wide-ranging study of the genetic, physical, mental, and emotional characteristics of centenarians by Harvard University’s Thomas Perls suggests that genetic factors play a large role in longevity, although Perls also acknowledges the importance of lifestyle and attitude.5

Christine L. Himes is associate professor of sociology and senior research analyst at the Center for Policy Research at Syracuse University.

Excerpted from PRB’s Population Bulletin “Elderly Americans,” by Christine L. Himes.

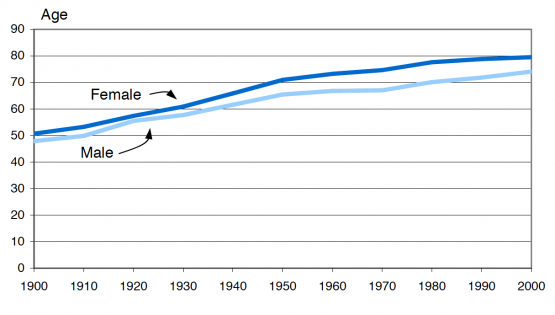

(December 2002) Life expectancy is a hypothetical measure. It represents the average number of additional years that a person could expect to live if current mortality trends were to continue for the rest of that person’s life. But death rates do not remain fixed over time. They have fallen steadily over the past century. Between 1900 and 2000, life expectancy in the United States increased from 51 to 80 for females and from 48 to 74 for males.

Source: AmeriStat, analysis of data from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Most of the improvements in life expectancy have resulted from reductions in infectious diseases among infants and children. The decline in mortality rates for these major killers has been attributed to improvements in public health efforts, medical technologies, and standards of living and hygiene. Today, the leading causes of death are cardiovascular disease (heart disease), malignant neoplasms (cancer), and cerebrovascular disease (stroke).

Data on long-term mortality trends have to be used with caution because, in the early decades of the 20th century, not all states participated in national death registration. Also, coverage was incomplete, especially for the poor and for racial minorities. Classification of causes of death depends on the medical knowledge and qualifications of the people attending the death. Historians have argued, for example, that many of the deaths ascribed in the early years of this century to other causes, or to indeterminate ones, were actually hard-to-diagnose cases of cardiovascular disease. The categories change over time, but the trends shown in these data for the overall risk of death and the major groups of causes are considered valid.

References

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, Older Americans 2000: Key Indicators of Well-Being (2000): Table 12A; A.M. Minino et al., “Deaths: Final Data for 2000,” National Vital Statistics Reports 50, no. 15 (2002).

November 20, 2000

(November 2000) Three quarters of older American men live in a family setting, while only half of older American women do. In 1999, 9.8 million people ages 65 and older lived alone, 77 percent of whom were women. The percentage of older people living alone increases with age. In 1999, about 15 percent of men and 31 percent of women ages 65 to 74 lived alone, but among those 75 and older, 20 percent of men and 51 percent of women lived alone. The percentage of women ages 75 and older living alone has increased by 10 percentage points since 1970.

The percentage of older people residing in institutions has been declining in recent years. According to the National Nursing Home Survey, the percentage of people ages 85 and older residing in nursing homes declined from 22 percent in 1985 to 19 percent in 1997. Among people ages 75 to 84, the percentage in nursing homes declined from 6 percent in 1985 to 5 percent in 1997. This decline may reflect the decline in disability rates among the older population, reported by several sources, and the increase in the availability of home health services over this period. Though the percentage of older people in nursing homes declined, the absolute number of older people in nursing homes increased, from 1.3 million in 1985 to 1.5 million in 1997, because the total number of older people in the population has increased.

Most of the data, charts, and graphs on the older population are based on tabulations from the Census Bureau’s March Current Population Survey (CPS).