United Nations Raises Projected World Population

The United Nations Population Division has just released its comprehensive estimates and projections, World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision. The results show a larger global population size in 2050, 9.6 billion, up from the 9.3 billion that the UN projected in its 2010 Revision. A major reason for the higher projection is higher fertility (birth rates) in some countries than previously estimated, particularly in Africa. Much of that information comes from recent demographic surveys.

The overall pattern of projected growth in the developed and developing countries is shown in Figure 1, a pattern that has changed little over the years. Before looking at more-detailed results, however, it is important to take a careful look at the assumptions demographers must make in producing projections.

Figure 1

World Population, 1950–2050

Source: United Nations Population Division, World Population Prospects, the 2012 Revision (Medium Variant).

Making the Assumptions

Any projection involves speculating about the future and just how populations might grow or decline and just how slowly or quickly they might do that. Fertility is a powerful determinant, and is represented by the total fertility rate (TFR, or the average number of children per woman). Globally, past and present trends in the TFR vary widely. There are countries with high TFRs, 5 children or more, where births are either not coming down or are doing so very slowly; others have decreased to moderate levels, leaving open the question of whether their TFRs will continue to decline; still others have declined to very low, even historically low, levels and show little sign of increasing. In making projections, these issues must obviously be addressed. There is always the option of making more than one projection with different assumptions in order to consider other possible paths. The UN does this, although its middle scenario, the Medium Variant, is by far the one most often quoted. Future mortality, the second component of population change, also requires assumptions. This is truer in countries with relatively high mortality and low life expectancy, where there may be considerable room for improvement. Finally, immigration plays a significant role in some countries.

Of those three components, fertility frequently plays the most important role, particularly when it is high or very low. How might one project the future of the TFR? It has been customary to assume that the TFR in higher fertility countries will decline in a pattern similar to what happened in countries that have experienced TFR decline.

For example, here are three countries with varying fertility levels: Niger, Pakistan, and Germany. In Niger, the 2012 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) put the TFR at 7.6 children per woman, actually higher than the TFR from a DHS conducted six years earlier. The UN assumes that Niger’s TFR may decline to 5 children per woman by mid-century, certainly a reasonable assumption, but one that is also a full child higher in 2050 than was assumed in the UN’s 2010 round of projections. In 2010, the UN had projected a 2050 population of 55 million for Niger, up from about 17 million, but the new projection is 69 million. Projections are indeed a continuous process of evaluation and revision.

The UN Medium Variant clearly assumes that the effective use of family planning will result in reductions in TFRs, even where it appears not to be taking place. As John Wilmoth, director of the United Nations Population Division, stated: “The medium-variant projection is thus an expression of what should be possible if future patterns of behavioral change in childbearing resemble those of the past, for populations at similar levels of fertility. These future trends, however, are not guaranteed. In fact, in light of recent trends for some high-fertility countries, this middle scenario could require additional substantial efforts to make it possible.”

Pakistan has been experiencing fertility decline in recent years and the UN has assumed that trend will continue. However, there have been numerous cases in which the TFR declined to some lower value but the decline then “stalled.” Pakistan may be one of these cases. Germany has had very low fertility for about 40 years. For Germany, the UN assumes that there will be very modest “recovery” in the TFR to about 1.7 children from the current 1.36. Although there has been no TFR increase yet, the assumption does not seem extreme.

For world regions, sub-Saharan Africa is projected to have the largest growth of 1.2 billion by 2050, even more than population giant Asia. For other world regions, growth is projected to be far more modest, and population decline is expected in Europe. Sub-Saharan Africa is also the region with the greatest possible future variation, given its high fertility and uncertain future fertility trends (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Current and Projected Population Totals by World Region

Source: United Nations Population Division, World Population Prospects, the 2010 and 2012 Revisions (Medium Variants).

The Other Scenarios

The UN produces three main scenarios: Low, Middle, and High variants. The Low and High variants are similar to the Medium except that the TFR is one-half child less and one-half child more than the Medium. Under these three variants, world population in 2050 is projected at 8.3 billion (low), 9.6 billion (medium), and 10.9 billion (high). The largest variation by far is among the less developed countries. The UN also produces projections to illustrate the impact of demographic trends, although these are somewhat unlikely. For fertility, there is a Constant Fertility projection as well as an Instant Replacement, showing what would happen if all countries suddenly had TFRs of 2.1. In the case of Niger, the Constant Fertility Variant is 86 million population in 2050, growing at a rate that would double its population every 16 years. While such growth would certainly be unsustainable, this scenario greatly improves our understanding of population dynamics. The Zero Migration Variant projects a U.S. population in 2050 of 344 million instead of 401 million as in the Medium Variant.

The UN has also run its projections toward a more distant “horizon”—to 2100. While that is very far into the future, it is informative to look at the long-term consequences of earlier trends. It also reminds us that many countries will continue growing (or declining) after 2050. The projections range from 6.8 billion (low) to 10.9 billion (medium) to 16.6 billion (high). Under the High Variant, sub-Saharan Africa’s population would rise to 5.4 billion.

The UN projection series is more than just a “forecasting” project, it’s a valuable tool that quantifies a variety of aspects of demographic change, giving us a thorough examination of the demographic world we will live in and why. The full set of projections is available at: http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/index.htm.

In Arab Countries, Mobile Internet and Social Media Are Dominant, but Disparities in Access Remain

(May 2012) Arab countries continue to rapidly gain access to mobile cellular and to a smaller extent, mobile and wireless Internet, but lag behind in access to fixed broadband Internet access at home, according to the report ICT Adoption and Prospects in the Arab Region 2012.1 Published by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), the report examines information and communications technologies (ICT) trends throughout the region and identifies ICT areas that need policy attention.

More people in Arab countries are online largely because of the increasing spread of mobile 3G networks that give people access to the Internet on their mobile phones, and the increasing number of computers accessing the Internet via wireless networks. As of the end of 2011, 30 percent of the population in the region was using the Internet. This is comparable to the Asia/Pacific region (27 percent) and higher than sub-Saharan Africa at 13 percent. Europe has the highest level of internet use (74 percent) followed by the Americas (56 percent).

For Internet Access, Mobile Rules

The largest improvement in Internet and communications technology has been in the mobile sector. Mobile communication access has expanded rapidly in the region in recent years, catching up to the levels of developed countries. The number of mobile cellular subscriptions has almost tripled from 2006 to the end of 2011, from 126 million to 350 million. As of the end of 2011, mobile cellular penetration in Arab countries is at 97 per 100 people, 19 points higher than the world average. In comparison, Asia/Pacific is at 74, sub-Saharan Africa is at 53, while the Commonwealth of Independent States leads at 143, followed by Europe at 120 and the Americas at 103.

People in the Middle East and North Africa overwhelmingly access the Internet via mobile phones. But the almost-ubiquitous access to cellular service on mobile phones does not automatically entail access to the Internet via mobile devices. Although it has grown faster than the developing-country average, mobile broadband, at 13 per 100 people, is still below the world average of 17 per 100 people. A lack of competition and infrastructure continue to hamper more rapid growth of mobile Internet access. And connectivity is an issue. “There are issues of speed and network congestion that might need to be addressed. Some mobile broadband services/subscriptions have data volume restrictions or lower the speed after a certain amount of data downloaded,” says Susan Teltscher, head of the ICT Data and Statistics Division at ITU.

While 26 percent of households in Arab countries have Internet access, most of that is through wireless networks. High-speed fixed broadband access remains very limited, partly due to the historically low levels of fixed phone lines throughout the region. The level of fixed phone access peaked at only 10 percent in 2008. Only sub-Saharan Africa, at 1.4 percent, has a lower rate of access. The lack of an existing fixed-phone-line infrastructure makes it more difficult to expand fixed broadband access. According to Teltscher, “The limited fixed line network has impacted in particular the broadband uptake via Digital Subscriber Lines (DSL), globally the most widespread fixed-broadband technology.”

Disparities Across Region and Within Countries

The Arab region, as defined by the ITU, includes a diverse set of countries, with varying income levels. GNI per capita ranges from $1,180 in Comoros to $33,690 in Bahrain.2 The Gulf Cooperation Council (GGC) countries, well known for their wealth and oil exports, are the region’s richest countries, with GNI per capita of at least $15,000. Not surprisingly, there is a strong link between income level and access to Internet communication and technology. But there are outliers. Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia, all with a GNI per capita of well under $10,000, have high levels of ICT use.

The figure shows the disparity between GCC and non-GCC countries. Libya is an exception among non-GCC countries, with mobile broadband penetration of almost 43 per 100 people, a rate more comparable with GCC countries due to heavy government support to compensate for a lack of fixed broadband and the fact that Libya is an oil-rich country with GNI per capita of $16,400.

Fixed and Mobile Broadband Internet Subscription Rate, Selected Arab Countries, 2010

(per 100 people)

Source: International Telecommunications Union, ICT Adoption and Prospects in the Arab Region 2012 (Geneva: ITU, 2012).

Foreign Social Media Sites Widely Popular

Two trends stand out when examining the most popular sites in the region: American sites are consistently the most popular and social media makes up a majority of Internet use. Google, Facebook, and YouTube are consistently among the five most-visited sites in every country in the region with available data.

However, the amount of local Arabic content is increasing. Online portals and smartphone mobile apps are the largest area of growth for local content. Arabic Internet domain names are increasingly available. In May 2010, Egypt became the first Arab country to introduce Arabic domain names.

Internet users in MENA are not passive readers of news and information. Blogging services, online forums, and file-sharing services—all participatory and interactive—dominate the lists of most-popular sites. To take just a few examples of countries with recent political unrest, the 10 most-visited sites in Bahrain include Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Blogspot. In Egypt, Facebook, YouTube, Blogspot, and Fatakat (an online forum) are among the most popular. And in Yemen, Facebook, YouTube, live.com (an email portal), and Blogspot are some of the most popular sites.

Policy Recommendations

There is increasing focus among policymakers and international organizations on improving access to high-speed broadband. The Connect Arab Summit 2012 dealt with this issue extensively. Why is it important to improve access to broadband? The World Bank estimates that a 10 percent increase in broadband penetration in a country can raise GDP by around 1.4 percent. In addition, expanding broadband creates jobs. Digital services and outsourcing for large companies can create jobs, especially among youth and women, as broadband access increases.3

In addition, the ITU recommends lowering prices for digital services, improving ICT literacy levels, and making more content locally based to increase access and use in the region. Other policy recommendations include enforcing copyright and antipiracy laws.

As for the future, Teltscher says, “Internet access and use in the region will continue to grow over the next few years. It is likely that much of the growth will occur through wireless networks.”

Eric Zuehlke is web communications manager at the Population Reference Bureau.

References

- The 21 ITU Member States of the Arab region are: Algeria, Bahrain, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.

- Carl Haub and Toshiko Kaneda,2011 World Population Data Sheet (Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau, 2011).

- International Telecommunications Union, “ITU Interviews @ CAS12: Carlo Rossotto, MENA Regional Coordinator, ICT, World Bank,” accessed on April 10, 2012.

Premature Births Help Explain Higher U.S. Infant Mortality Rate

Date

December 15, 2009

Author

PRB

(December 2009) The United States—one of the world’s wealthiest countries—consistently has higher infant mortality rates than most other developed countries. In 2005, 29 countries had lower rates, including Cuba and Poland.1 The United States has seen little improvement in its infant mortality rate since 2000. In 2007, 6.8 of every 1,000 U.S. babies died before their first birthday, not much better than the 6.9 per 1,000 rate in 2000.2 In comparison, the lowest rates, in Singapore, Sweden, and Japan for example, are below 2.6.

A new report from the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics finds that a higher rate of premature births in the United States is the main reason for this poor ranking on infant mortality.3 In 2004, one in eight U.S. births (12.4 percent) were preterm—born before 37 weeks of gestation—much higher than recorded in most European countries, and double the proportion in Ireland, Finland, and Greece (see figure). Most fully developed babies are born at 37 to 42 weeks of gestation.

Percentage of Premature Births Higher in the United States Than in Europe, 2004

Note: Includes births of 22 to 36 weeks gestation. Earlier births were excluded to make the figures more comparable.

Source: Marian F. MacDorman and T.J. Mathews, “Behind International Rankings of Infant Mortality: How the United States Compares With Europe,” NCHS Data Brief, no. 23 (2009): figure 3.

Preterm babies have a higher risk of complications that could lead to death within the first year of life. Their lungs and digestive systems are often not fully developed, and they face a higher risk of brain damage.4 In the United States, more than one-third of infant deaths are related to a premature birth.5

The percentage of U.S. births delivered prematurely rose more than 20 percent between 1990 and 2006. This rise has been tied to several interrelated trends, including an increase in multiple births, greater reliance on Caesarean deliveries and induced labor to manage risky pregnancies, and an increase in births to older mothers. Other maternal factors are also associated with premature births, including behavioral and socioeconomic characteristics such as smoking, teenage pregnancy, obesity, poverty, and inadequate prenatal care.6

There is a racial gap in the percentage of premature births in the United States, linked to the persistent disparity in infant mortality among African Americans and whites.7 In 2006, nearly one in five African American babies was born prematurely, compared with one in eight non-Hispanic white babies. African American mothers tend to have many of the socioeconomic characteristics that have been linked to premature births. African American babies die at twice the rate of white babies.

But racial disparities do not fully explain the poor U.S. ranking in infant mortality. Non-Hispanic white Americans still have higher rates than the average in many developed countries. And the preterm rate has increased fastest for white mothers, who tend to be older and more likely to use infertility treatments than minority women—factors that raise the likelihood of multiple births.

The National Center for Health Statistics study found that the U.S. health care system does a good job of saving premature babies—better than in many European countries—but there are too many of them born. Preventing preterm births is crucial to lowering the U.S. infant mortality rate.

Mary Mederios Kent is senior demographic editor at the Population Reference Bureau.

References

- Marian F. MacDorman and T.J. Mathews, “Behind International Rankings of Infant Mortality: How the United States Compares With Europe,” NCHS Data Brief, no. 23 (2009).

- Jiaquan Xu, Kenneth D. Kochaneck, and Betzaida Tejada-Vera, “Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2007,” National Vital Statistics Reports 58, no. 1 (2009): 6.

- MacDorman and Mathews, “Behind International Rankings of Infant Mortality.”

- The March of Dimes, “Preterm Labor and Birth: A Serious Complication,” accessed online at www.marchofdimes.com/pnhec/188_1080.asp, on Dec. 10, 2009.

- Joyce A Martin et al., “Births: Final Data for 2006,” National Vital Statistics Reports 57, no. 7 (2009): 17-18.

- March of Dimes, “Preterm Labor and Birth”; and Melonie Heron et al., “Deaths: Final Data for 2006,” National Vital Statistics Reports 57, no. 14 (2009): table D.

- Martin et al., “Births: Final Data for 2006”: 18; and Rogelio Saenz, “The Growing Color Divide in U.S. Infant Mortality,” accessed online on Dec. 10, 2009.

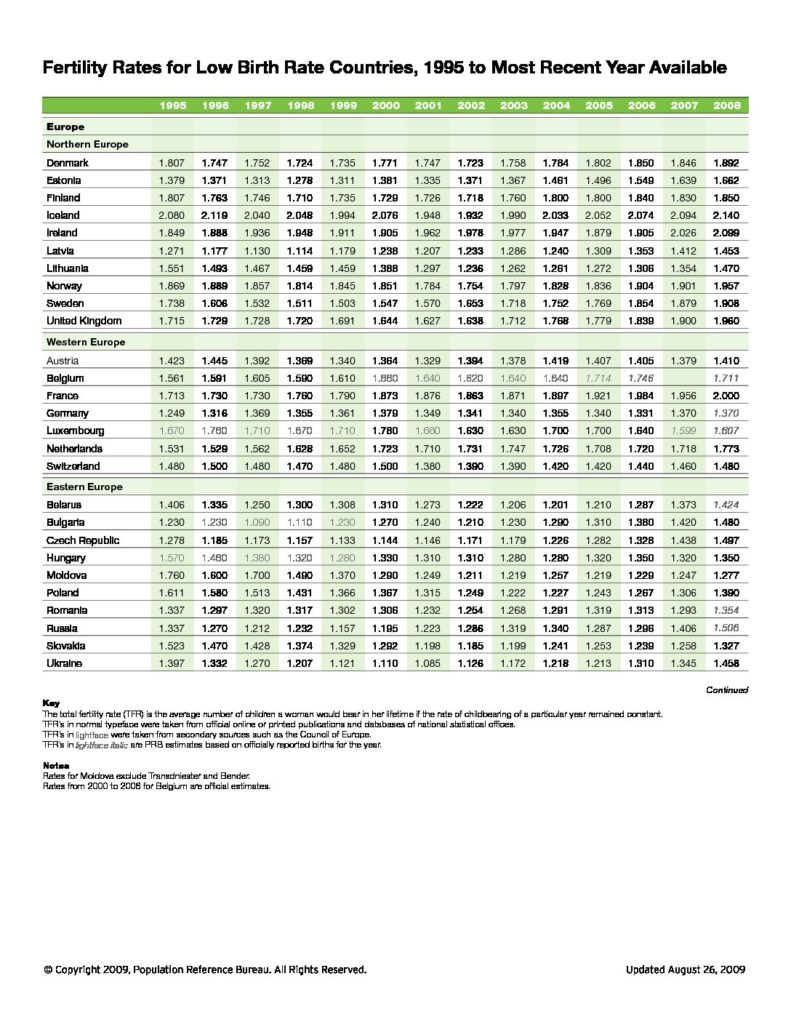

Birth Rates Rising in Some Low Birth-Rate Countries

(September 2009) “1.57 Shock” was a popular media phrase in Japan back in 1990 after the fertility rate (TFR) fell to its lowest value ever: 1.57 lifetime births per woman, recorded for 1989.1 This was even below the 1.58 children per woman reached during the inauspicious year of the Fire Horse—1966. But the deep fertility decline of the 1990 “shock” was different because it signaled a long-term trend. Couples were delaying marriage and drastically reducing their family size for very practical reasons, such as the high cost of living and the difficulties of raising children in two-earner urban families. Nearly two decades later, Japan’s TFR is still below the 1989 rate. It was 1.37 in 2008.

Japan was following similar trends in other industrialized countries when its fertility declined to such low levels.2 In the 1990s, a new sociological phenomenon emerged: birth rates so low that countries could easily see population decline in their futures, along with unprecedented population aging. True, France had worried about population decline in the 1930s, but the French TFR never fell below 2.0 during those years. Some European countries later feared decline because of famine after World War II. But after 2000, concern over low fertility reached a crescendo: Such phrases as “population implosion,” “demographic suicide,” “demographic winter,” and the like appeared regularly in the media.

Patterns of Fertility Increase

Has fertility bottomed out and begun to rise in any of these countries? Answering such a question can be tricky because fertility trends follow different patterns from country to country. A country’s TFR may begin to rise, decline for a time, and then rise again (Russia). Or, it may increase and turn back downward (South Korea). Countries whose low point occurred relatively recently have had less time to “recover” (Portugal).

In the listing below, the lowest fertility countries have been grouped by several objective criteria. All are countries whose TFRs had declined to 1.6 or lower. Those who have experienced an increase in the TFR of 0.3 or more belong to Group A and could be considered “risers.” Group B are those whose TFRs have increased less than 0.3 (usually much less) or, in the case of Taiwan, are still declining. Nonetheless, there has been a nearly universal tendency for low TFRs to rise in low birth-rate countries, or to have at least bottomed out. It does appear that the trend of declining fertility in these countries has ended for now.

Fertility Trends in Very Low-Fertility Countries

| Group A. Very Low-Fertility Countries With Notable Fertility Increases† | Group B. Very Low-Fertility Countries* With Slight or No Fertility Increase or Continuing Decline |

|---|---|

| Northern Europe | Western Europe |

| Estonia | Austria |

| Latvia | Belgium |

| Sweden | Germany |

| United Kingdom | Luxembourg |

| Eastern Europe | Switzerland |

| Bulgaria | Eastern Europe |

| Czech Republic | Belarus |

| Russia | Hungary |

| Ukraine | Moldova |

| Southern Europe | Poland |

| Slovenia | Romania |

| Spain | Southern Europe |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina | |

| Croatia | |

| Greece | |

| Italy | |

| Macedonia | |

| Malta | |

| Montenegro | |

| Portugal | |

| Asia | |

| China, Hong Kong SAR | |

| Japan | |

| Singapore | |

| South Korea | |

| Taiwan** | |

| Americas | |

| Canada | |

| Cuba | |

| † Countries whose TFR had declined to 1.6 or less and whose TFR has risen at least 0.3 from the low point. | * Countries whose TFR had declined to 1.6 or less. ** Continuing decline. |

Note: Hong Kong SAR is a Special Administrative Region of China.

Where fertility is increasing, it is often a result of delayed childbearing caused by a long-term shift in childbearing patterns or by marriages delayed by an unfavorable economy. In Sweden, the peak age group of childbearing for women is now 30 to 34, up from 25 to 29 in 2001. In Russia, childbearing below age 25 dropped sharply after 1990 so that women ages 25 to 29 are just as likely to have a birth as those ages 20 to 24. A similar pattern has emerged in Ukraine.

Fertility can also appear to rise and then suddenly fall, as it did in South Korea between 2006 and 2008. South Korea’s TFR rose in 2006, the Year of the Dog, an auspicious year for marriages, and in 2007, the Year of the Golden Pig, auspicious for births. After a flurry of marriages and births in those years, the TFR slipped to 1.192 in 2008, one of the lowest in the country’s history.

Immigration, Government Policies Can Affect Fertility Rates

Sometimes a TFR increase is generated by births to immigrants. In 2007, the rise in births in Spain was completely due to births to immigrant women (births to Spanish-born women actually declined). Two-thirds of the increase in births in the United Kingdom between 2001 and 2007 were births to foreign-born women.

Many governments have moved to address the problem of low fertility and extreme societal aging. In Russia, couples can receive about $9,000, a huge sum, for a second or subsequent child. Child payments are lower in Ukraine, but are still significant. Singapore has introduced beneficial tax packages and lengthened government-subsidized maternity leave from 12 to 16 weeks. Spain introduced a 2,500 Euro payment for each birth. Other countries debate ways to encourage childbearing, without reaching a consensus. In Japan, there has been much discussion in government and the media on steps that might be taken but little has actually been done. The very slight rise in births from 2007 to 2008, heralded in the press, was almost entirely due to births to non-Japanese resident in the country.

Will Economic Recession Depress Births?

There has been much discussion about the possible effect of the worldwide recession on birth rates. Early reports of monthly births seem to suggest that fertility kept rising in a number of countries. In Russia, there were 37,800 more births reported in the first half of 2009 than for the same period in 2008. That was slower than the increase from 2007 to 2008, but a sizable increase nonetheless. In Poland, births were nearly 10 percent higher in the first half of 2009 than in 2008, a rate of increase that would likely make Poland a “riser,” as defined above. In Taiwan, which currently has the world’s lowest fertility, the number of births through the end of July 2009 decreased slightly. The future course of birth rates in these countries with extremely low fertility will have long-lasting consequences. As data on the latest trends become available, they will be posted to the PRB website.

Carl Haub is a senior demographer and Conrad Taeuber Chair of Public Information at the Population Reference Bureau.

References

- The TFR is the average number of children a woman would have during her lifetime if the birth rate of a particular year were to remain constant.

- The term industrialized, as used here, covers countries considered more developed by the United Nations plus a number of less developed countries often referred to as newly industrialized, such as South Korea. Only countries whose registration of births is considered complete are included.

Urban Population to Become the New Majority Worldwide

(July 2007) For the first time, more than half the world’s population will be living in cities and towns by next year, according to the State of World Population 2007 report from the United Nations. Less developed regions will hit the half-way point later, but likely before 2020. The urban percentage of the world’s population is projected to reach 60 percent by 2030 (see figure). The urban share is likely to rise from 75 percent to 81 percent in more developed countries between 2007 and 2030, and from 44 percent to 56 percent in less developed countries.

Percent Urban, 2007, 2015, and 2030

Source: United Nations Population Fund, State of World Population 2007; and United Nations Population Division, World Urbanization Prospects: The 2005 Revision (2006).

The 3.3 billion global urban population is expected to grow to 4.9 billion by 2030.

Growth in smaller cities and towns is expected to account for most of the urban population increase. Urbanized areas in Africa and Asia are forecast to grow most rapidly, doubling in population between 2000 and 2030, according to the UN Population Fund, which released the report.

Rural populations, meanwhile, are forecast to decrease by 28 million between 2005 and 2030, because of mortality among the older rural residents and migration of many younger residents to urban areas.

References

United Nations Population Division, World Urbanization Prospects: The 2005 Revision (2006), accessed online at www.un.org, on July 16, 20007.

United Nations Population Fund, State of World Population 2007: Unleashing the Potential of Urban Growth, accessed online at www.unfpa.org, on July 16, 2007.

Why Concentrated Poverty Fell in the United States in the 1990s

(August 2005) Concentrated poverty—often defined as the number of people living in neighborhoods with poverty rates exceeding 40 percent—fell substantially in the United States in the 1990s, according to a new report by the U.S. Census Bureau.1 In 1999, about 2.8 percent of the U.S. population lived in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty, down from 4.6 percent in 1989. Meanwhile, the number of people living in tracts with less than 20 percent in poverty increased over the decade, from 78.2 percent to 81.5 percent.2

Does this decline in concentrated poverty rates signal a structural change in poverty distribution in the United States, or does it merely reflect the improved U.S. economy of the 1990s? To answer this question, we need first to outline the history of poverty concentration in the United States and the factors that doubled the number of people living in poor U.S. neighborhoods during the 1970s and 1980s. At least one of the factors that contributed to that trend—suburbanization—also likely played a role in its reversal during the following decade.

The Spatial Concentration of U.S. Poverty

The number of people living in high–poverty neighborhoods is significant because many urban problems such as crime, unemployment, welfare dependency, drug use, substandard educational outcomes, and out–of–wedlock births are most prevalent in high–poverty areas.3 People in high–poverty neighborhoods are also more likely than others to live in female–householder families, have lower family incomes, and not own their own house. In essence, poor people living in these neighborhoods are often both spatially and socially isolated from mainstream society. Their families must therefore cope not only with their own poverty, but also with the poverty and its accompanying problems of hundreds of other families near them.4

However, the spatial concentration of poverty in American cities is a relatively recent phenomenon.5 Social historians who have reconstructed 19th–century U.S. urban neighborhoods have shown that, with some exceptions in large cities, the poor were generally clustered into pockets and alleyways near the homes of the affluent.6 Class and racial segregation began increasing by 1920 with improvements in transportation and the rise of the automobile industry, which made the suburban lifestyle more accessible. After World War II, suburbanization surged dramatically; early suburban migrants were overwhelming white and middle class.

But it was not until the 1960s and 1970s when many commentators began noting sharp increases in concentrated poverty. And researcher Paul Jargowsky (who is widely regarded as having done the most research into the patterns of concentrated poverty) notes that the number of people living in high–poverty neighborhoods nearly doubled from 1970 to 1990, from a little over 4 million to 8 million people. Nearly one–half of the people living in these poverty areas in 1990 were themselves poor, though only 15 percent of the total poverty population lived in such neighborhoods.7

The rise in concentrated poverty in the 20th century resulted from several factors:

- Some federal housing policies, such as the building of low–income projects in already poor inner–city neighborhoods in the post–World War II period, contributed to poverty concentration. Federal assistance to highway construction also accelerated the suburbanization of the middle and upper class.8

- The elimination of low–skill manufacturing jobs and the deconcentration of employment from central cities to surrounding suburbs increased concentrated poverty in those cities—a “spatial mismatch” between workers and employment opportunities.9

- Similarly, the emergence of the service economy resulted in the lack of good–paying job opportunities to match the skills of inner–city residents—a “skills mismatch” whose impact may have been greater among African Americans, who were overrepresented in manufacturing jobs and more likely to live in inner cities.10

- Real estate brokers, speculators, developers, banks, and local governments—acting on racial animosity within the population—preserved racial divisions in housing markets by steering members of different racial and ethnic groups to different neighborhoods, denying loans on the basis of race, and passing ordinances establishing separate neighborhoods for whites and blacks.11

- Others have argued that welfare policy and changes in norms contributed to concentrated poverty during the period by making some people less self–reliant and providing positive incentives for out–of–wedlock births and female–headed households.12

Which of these factors are the most salient for understanding patterns of concentrated poverty from 1970 to 1990? In his book Poverty and Place, Jargowsky concluded that economic opportunities were the most important factor determining these patterns, and that neighborhood sorting processes—such as residential segregation and the growing economic segregation among African Americans—also played important roles.13

A Good Economy and Suburbanization Help, But Pockets of Poverty Remain

The recent Census Bureau report follows a 2003 report by Jargowsky that first documented the dramatic new trends in poverty concentration in the 1990s. Jargowsky’s research indicated that the number of people living in high poverty neighborhoods declined by 25 percent in the 1990s, with the steepest declines among African Americans. He found that about 19 percent of poor African Americans lived in high–poverty areas in 2000, down from 30 percent in 1990. Declines in concentrated poverty occurred primarily in central cities and rural areas; the suburbs experienced little change in the 1990s.14

These declines, particularly among African Americans, illustrate the importance of economic processes. After a recession in the early 1990s, the overall U.S. poverty rate fell from a high of 15.1 percent in 1993 to 11.3 percent in 2000. Over the same period, the poverty rate among African–Americans fell from 33.1 percent to an all–time low of 22.5 percent.15 These trends likely prompted declines in concentrated poverty just by making poverty as a whole less prevalent.

Increasing suburbanization among minorities of all income levels in the last couple of decades also helps explain why declines in concentrated poverty in inner cities were accompanied by little change in concentrated poverty in the suburbs. 16 For example, racial and ethnic minorities made up more than one–quarter (27 percent) of the suburban population in the 100 largest metropolitan areas in 2000, up from 19 percent in 1990. Minorities were also responsible for most of the suburban population growth in these metropolitan areas over that period.17 In addition, suburbs have also become economically more diverse since 1980.18 The implication of these trends is that, had it not been for the strong economy and declining poverty rates for all groups in the 1990s, the decade may have seen increasing poverty concentration in the suburbs.

Despite declines in concentrated poverty in the 1990s, traditionally disadvantaged groups such as African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, children, and people with less than a high school degree were among those still over–represented in high–poverty neighborhoods, according to the Census Bureau report.

Based on current patterns of suburbanization and overall long–run declines in poverty among African Americans, it is unlikely that concentrated poverty will increase in inner cities in the coming years. It is quite possible, however, that some suburban areas may experience growing poverty: Both low–income residents and immigrants are increasingly moving to the suburbs rather than settling in central cities.

In addition, as Jargowsky has observed, Hispanics will likely represent a larger share of those living in high poverty areas because of the overall rapid growth of this group. Finally, a sharp economic recession could potentially increase poverty concentration for all groups.

John Iceland is an associate professor of sociology at the University of Maryland–College Park and is also a faculty associate of the Maryland Population Research Center. He was chief of the Poverty and Health Statistics Branch at the U.S. Census Bureau until 2003.

References

- Alemayehu Bishaw, Areas with Concentrated Poverty: 1999, U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000 Special Reports, #CENSR–16 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2005). This new report provides state–by–state level detail and information on the socioeconomic and demographic composition of those living in concentrated poverty—not only by race and ethnicity, but also by education, age, marital status, unemployment status, family size, type of family, residential mobility, family income, and home ownership.

- The Census Bureau report presents information neighborhoods with poverty rates from: 0.0 to 12.3 percent, 12.4 to 19.9 percent, 20.0 to 39.9 percent, and 40.0 percent or higher. Tracts with a poverty rate of 20 percent or higher are referred to in the report as “poverty areas.”

- Paul Jargowsky, Poverty and Place: Ghettos, Barrios, and the American City (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1997).

- Jargowsky, Poverty and Place; and William Julius Wilson, The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987).

- John Iceland, Poverty in America (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2003): 52–9.

- Thomas J. Sugrue, “The Structure of Urban Poverty: The Reorganization of Space and Work in Three Periods of American History,” in The “Underclass” Debate: Views from History, ed. Michael B. Katz (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993): 92–3.

- Jargowsky, Poverty and Place: 38–43.

- Michael G.H. McGeary, “Ghetto Poverty and Federal Policies and Programs,” in Inner–City Poverty in the United States, eds. Laurence Lynn, Jr. and Michael McGeary (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1990).

- John F. Kain, “Housing Segregation, Negro Employment, and Metropolitan Decentralization,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 82, no. 2 (1968): 175–97.

- For more on skills mismatches, see Harry J. Holzer, “The Spatial Mismatch Hypothesis: What Has the Evidence Shown?” Urban Studies 28, no. 1 (1991): 105–22; John Kasarda, “Structural Factors Affecting the Location and Timing of Underclass Growth,” Urban Geography 11, no. 3 (1990), 234–64; and Wilson, The Truly Disadvantaged.

- Douglas S. Massey and Nancy Denton, American Apartheid (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993).

- Two influential proponents of this view are Charles Murray, Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950–1980 (New York: Basic Books, 1984); and Lawrence Mead, The New Politics of Poverty: The Nonworking Poor in America (New York: Basic Books, 1992).

- Jargowsky, Poverty and Place: 183.

- Paul Jargowsky, Stunning Progress, Hidden Problems: The Dramatic Decline of Concentrated Poverty in the 1990s (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2003): 1.

- Joseph Dalaker, Poverty in the United States: 2000, U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, Series P60–214 (2001): 18-20.

- William H. Frey, Melting Pot Suburbs: A Census 2000 Study of Suburban Diversity (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2001).

- Frey, Melting Pot Suburbs.

- Todd Swanstrom, Economic Segregation among Suburbs and Central Cities in Major Metropolitan Areas (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, October 2004).

Why Do Canadians Outlive Americans?

This article is adapted with permission from Barbara Boyle Torrey and Carl Haub’s article “A Comparison of U.S. and Canadian Mortality in 1998,” Population and Development Review 30, no. 3 (2004).

(November 2004) Over 250,000 Americans who died in 1998—roughly one of every ten U.S. deaths that year—would have survived had they been Canadian, according to a comparison of patterns of death between the two countries.

And such “excess deaths” in the United States have been growing in number for over 40 years. In 1955, Americans and Canadians had almost the same life expectancy at birth. In 1998, however, life expectancy at birth was 76.7 years in the United States and 78.8 years in its northern neighbor—a notable divergence at a time when life expectancy among high-income countries was tending to converge.1

Why do Americans die an average of 2.1 years earlier than Canadians? Using basic mortality data for the two countries for 1998, we find that obesity appears to be a major suspect in the disparities.

Canada and the United States: A Natural Comparison

Canada and the United States resemble each other more than they do any other country. They share a language, a continent, and a border. They are also both younger than their European allies, have resource-based economies, and are two of the wealthiest countries in the world. These similarities create a natural opportunity to study why the two countries differ so much in both life expectancy and death rates.

We calculate the numbers of deaths by age and sex that would have occurred in the United States on the assumption that Canadian mortality rates prevailed in the 1998 U.S. population.2 We use seven broad categories of cause of death (neoplasm, suicide, diabetes, homicide, injury, respiratory diseases, and circulatory diseases) developed by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). In 1998, these causes accounted for 84 percent of all U.S. deaths.

Figure 1

Percent Distribution of Excess U.S. Deaths Relative to Canada by Sex and Race for Three Age Groups, 1998

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, unpublished file NESTV 98; National Center for Health Statistics, “Death Rates for 282 Selected Causes by 5-Year Age Groups, Race and Sex: United States 1979–1998”; and Statistics Canada, Mortality—1998 Shelf Tables.

Figure 2

Excess U.S. Deaths Relative to Canada by Cause of Death: Both Sexes, Whites, and Nonwhites, 1998

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, unpublished file NESTV 98; National Center for Health Statistics, “Death Rates for 282 Selected Causes by 5-Year Age Groups, Race and Sex: United States 1979–1998”; and Statistics Canada, Mortality—1998 Shelf Tables.

By our calculations, the United States in 1998 had 253,237 excess deaths as compared with Canada—11 percent of all deaths in the U.S. that year.3 In absolute terms, excess American deaths relative to Canadian deaths were most prominent among middle-aged men and among older women (see Figure 1).

Since Canadian mortality rates are not disaggregated by ethnic or racial groups, we also compared death rates for the total Canadian population with American white and nonwhite death rates. In proportionate terms, 35 percent of all excess U.S. deaths occurred to nonwhites, a percentage twice as high as the share of nonwhites in the U.S. population in 1998. But even among the more homogenous white American population alone, there were 164,756 excess deaths in 1998 as compared with Canadians.

Three Major Suspects: Smoking, Hypertension, and Obesity

We found excess American deaths relative to Canadian deaths in five of the seven ICD categories (see Figure 2). One of these categories—circulatory diseases—constitutes the most important cause of death in both Canada and the United States and accounts for 68 percent of all American excess deaths.

Circulatory diseases—which include 34 separate conditions, including hypertensive diseases and congestive heart failure—were the cause of 95 percent of the excess deaths of all U.S. women over age 65 and also were the largest single category of deaths among men and women under age 65.

Since circulatory diseases are such a large proportion of excess deaths in the United States, we focused on the major behavioral risk factors for many of these diseases: smoking, hypertension, and obesity.4

A number of surveys over the years have measured the prevalence of smoking in Canada and the United States.5 But while the differences in smoking rates between the two countries are today not very great, Canada has historically had higher levels of smoking—suggesting that this behavior is not an important factor in the excess U.S. deaths from circulatory and other diseases.

As for hypertension, a recent study found similar prevalence in both countries—21.1 percent of all Canadians age 18 and older have the disease, versus 20.1 percent in the United States.6 But the study also found that a higher percentage of Canadians with hypertension go untreated for the condition, and that more Canadians (43 percent) are unaware of their hypertension than their U.S. counterparts (at 30 percent). Therefore, hypertension also cannot account for the excess American deaths.

And the percentage of “overweight” individuals—defined as having a Body Mass Index (BMI) over 25—has increased in both countries since 1970s. The most recent comparative data suggest that the prevalence of Canadian males with BMIs between 25 and 29.9 (at 44 percent) was actually higher than that of U.S. males (at 40 percent), and that the percentage of Canadian women in this BMI range was slightly lower than that of American women.

The Dead Weight of Obesity?

But comparisons of obesity rates between the two countries (with obesity defined as a BMI over 30) tell a sharply different story. In 1998, American men were twice as obese as Canadian men (28 percent of the total U.S. male population versus 13 percent for Canada). American women were three times as obese as Canadian women (34 percent versus 11 percent). Recent estimates of remaining life expectancy for people who are overweight and obese suggest that the consequences of these conditions are substantial.

And a 40-year follow-up of the famous community health study of Framingham, Mass. reported that life expectancy at age 40 there was reduced because of excess weight.7 The findings suggest that obesity can account for much of the 1.5-year difference in life expectancy between Canadian and American women at age 40 and more than half of the 1.3-year difference between Canadian and American men.

While a number of other factors—such as disparities in health care coverage—may be important in explaining the differences in death rates between Canadians and Americans, this analysis provides an important perspective on our own mortality. The comparisons of data on mortality and risk factors in Canada and the United States reinforce the validity of widely expressed concerns over obesity.

Barbara Boyle Torrey is a visiting scholar at PRB. Carl Haub is senior demographer and holds the Conrad Taeuber Chair of Public Information at PRB.

References

- Kevin M. White, “Longevity Advances in High-Income Countries, 1955-96,” Population and Development Review 28: 59-76.

- Deaths in Canada and the United States are recorded, respectively, by Statistics Canada and by the US National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) from provincial and state vital statistics registers.

- Using an age-sex distribution other than that of the 1998 U.S. population (but broadly similar to it—for example, the age-sex distribution of the Canadian population) as the standard would change these precise numerical results, but not their general magnitude.

- J.M. McGinnis and W. H. Foege, “Actual Causes of Death in the United States,” JAMA 270, no. 18 (1993): 2207-2212.

- See Jason Gilmore, “Body Mass Index and Health,” Health Reports, Statistics Canada 11 (1999): 31-43; and “U.S. National Health Interview Survey” as reported in Health United States 2002 (Atlanta: Center for Disease Control and Prevention): 195-197.

- M.R. Joffres et al., “Distribution of Blood Pressure and Hypertension in Canada and the United States,” American Journal of Hypertension 14 (2001): 1099-1105.

- Anna Peeters et al., “Obesity in Adulthood and Its Consequences for Life Expectancy: A Life-Table Analysis,” Annals of Internal Medicine 138 (2003): 24-32.

Caribbean Countries Pay for Successfully Addressing Population Issues

Date

April 22, 2002

Author

PRB

(April 2002) In a move that marks the Caribbean’s success in various spheres of socioeconomic activity, international funding agencies are reducing their financial support for the region’s sexual and reproductive health programs. The move could adversely affect the delivery of population services — including those designed to stop the spread of HIV/AIDS — unless alternate sources of funding are found.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), and the World Bank have all signaled that the region has achieved success in socioeconomic development (including various population activities) and therefore should not continue to receive current levels of assistance. As a result, some countries will see their assistance phased out altogether while others will have their funding reduced over time.

Population Characteristics

This process of “graduation” from international assistance follows achievements in addressing a number of population problems. Infant mortality, birth rates, and population growth have declined during the last decade or so and the decline has been rapid in some cases.1 As a consequence, population growth has slowed while life expectancy at birth continues to rise.

Total fertility rates (TFRs) are expected to decline significantly for most countries over the next decade. In Belize, for example, the average number of children per woman is estimated to decline by more than 58 percent — from 5.4 in 1980-1985 to 2.6 in 2005-2010. A decline of some 53 percent is projected for Trinidad and Tobago, with the TFR dropping from 3.2 to 1.6 during the period.2 Haiti recorded the highest number of children per woman during 1980-1985 with 6.2, but this number is expected to decline by 40 percent (to 3.6) by 2005-2010.

Crude death rates or deaths per 1,000 people are also declining in the region. Countries estimated to record the highest declines during the periods 1980-1985 and 2005-2010 include Haiti (a 42.7 percent decline), Belize (35.1 percent), Guyana (23.9 percent), and the Dominican Republic (23.5 percent).

As a direct consequence of this declining mortality (from all causes of death including AIDS), life expectancy at birth has been increasing. Guadeloupe is estimated to record the highest life expectancy at birth of 76.0 years (males) and 82.5 years (females) during 2005-2010, an increase of 10.3 percent for men and 8.3 percent for women over the figures for the 1980-1985 period. Haiti (18.2 percent for males and 17.8 percent for females) is projected to record the highest percentage change in life expectancy during the 1980-1985 to 2005-2010 period, although the actual life expectancy at birth is estimated to be a modest 59.8 years for males and 62.8 years for females during 2005-2010.3

In line with declining fertility and mortality and limited net international migration, population growth rates are expected to remain low in the Caribbean.4 Cuba is expected to record the highest decline in the population growth rate, going from 0.8 percent during 1980-1985 to 0.3 percent during 2005-2010 — a nearly 63 percent drop. Estimates for Trinidad and Tobago show the growth rate falling from 1.7 percent during 1980-1985 to 0.5 percent in 1995-2000, before rising slightly to 0.7 percent in 2005-2010. The growth rate for the Dominican Republic is expected to go from 2.3 percent in 1980-1985 to 1.3 percent during 2005-2010, while in Jamaica the rate is expected to decline from 1.5 percent to 0.9 percent.

The Price

This overall success is costing the Caribbean international support for its population activities. UNFPA prioritizes and allocates funds to developing countries according to population needs. Most Caribbean countries have been placed in category B in the last five years (mid-level need) and slated for funding reduction, while the Bahamas and Barbados have been placed in category C (low-level need) and slated for a funding phase out.5

Many international agencies use the UNFPA classification to make funding decisions. The IPPF has announced its decision to phase out funding for some Caribbean countries and drastically implement a phased reduction in funds for many others. While the IPPF decision is also the result of a reduction in funding from the Federation’s own donors, other international agencies may follow suit. These cuts are expected to have a far-reaching impact. Until recently, for example, many Caribbean family planning programs received a substantial amount of funding from the IPPF.

While some governments already provide support for these programs, many are unlikely to be able to meet the funding shortfall. Governments such as Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago already spend substantial amounts of funds on their countries’ family planning programs. Others, including Grenada and Antigua and Barbuda, allow family planning associations to import supplies without customs duties and offer other non-cash concessions.

Emerging Population Issues

While the UNFPA reclassification was based on demographic data in the early to mid-1990s, new population challenges are emerging in the region. Notable among them are population aging, HIV/AIDS, and the need to sustain the levels of fertility, mortality, population growth, and related achievements that resulted in the reclassification.

Population Aging

Falling fertility and mortality and increasing life expectancy at birth provide a good mix for population aging and for increases in the proportion of older people in the population. The proportion of the population 65 years of age and older is expected to increase throughout the region between 1990 and 2020. In the Bahamas, where the largest percentage change is expected to occur, the proportion of the population 65 years old and older is expected to increase from 4.6 percent to 9 percent over the 30-year period. Cuba and Guyana are also expected to record massive changes in the proportion of older people.6 For Cuba, the proportion will increase from 8.4 percent to 15.8 percent. In Guyana the proportion of older people is expected to increase from 3.4 percent to 7.0 percent.

The increasing proportion of older people in the population brings with it a host of socioeconomic issues that will have to be addressed by these countries, including increased demand for health care, housing, recreation, transportation and other geriatric services and programs, with inherent implications for funding.

HIV/AIDS

The Caribbean has the second highest prevalence rate of HIV/AIDS in the world (2.2 percent) after sub-Saharan Africa (8.4 percent). While there are wide variations in the region, the largest number of people living with HIV/AIDS is found in Haiti where 200,000 adults ages 15-49 and 5,200 children under 15 years have the virus (see table below).

Table 1

Estimated Number of People Living with HIV/AIDS and Deaths by Country, 1999

| People living with HIV/AIDS | Deaths | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Adults (15-49) | Adult HIV prevalence rate | Women (15-49) | Children (0-15) | All ages |

| Bahamas | 6,800 | 4.13 | 2,200 | 150 | 500 |

| Barbados | 1,700 | 1.17 | 570 | <> | 130 |

| Belize | 2,400 | 2.01 | 590 | <> | 170 |

| Cuba | 1,950 | 0.03 | 450 | <> | 120 |

| Dominican Republic | 130,000 | 2.80 | 59,000 | 3,800 | 4,900 |

| Guyana | 15,000 | 3.01 | 4,900 | 140 | 900 |

| Haiti | 200,000 | 5.17 | 67,000 | 5,200 | 23,000 |

| Jamaica | 9,700 | 0.71 | 3,100 | 230 | 650 |

| Suriname | 2,900 | 1.26 | 950 | 110 | 210 |

| Trinidad & Tobago | 7,600 | 1.05 | 2,500 | 180 | 530 |

Source: Compiled from UNAIDS and WHO Epidemiological Fact Sheets.

The Dominican Republic follows Haiti with 130,000 adults and 3,800 children living with HIV or AIDS. Countries with moderate numbers of people living with HIV/AIDS include Guyana with 15,000 adults and 140 children, Jamaica with 9,700 adults and 230 children, Trinidad and Tobago with 7,600 adults, and the Bahamas with 6,800 adults and 150 children. Barbados, Cuba, Belize, and Suriname have the fewest people living with HIV/AIDS (see table above).

AIDS-related mortality is low in the Dominican Republic and moderate to high in the other countries, especially Haiti. The largest number of AIDS deaths in 1999 occurred in Haiti (23,000 deaths) and this constituted 11.2 percent of the total number of people living with the disease that year (see table above). The Dominican Republic recorded the second largest number of deaths with 4,900, but this constituted the lowest proportion of deaths of only 3.7 percent. Death proportions from AIDS were moderately higher in Cuba (5.6 percent) and Guyana (5.9 percent). The numbers were higher in the Bahamas (500 and 7.2 percent), Barbados (130 and 7.2 percent), Suriname (210 and 7.0 percent), Trinidad and Tobago (530 and 6.8 percent), and Belize (170 and 6.8 percent).

Most local family planning associations have been dealing with HIV/AIDS prevention at the grassroots level, including through programs in schools and through community outreach projects. According to the Barbados Ministry of Education, sexual activity is rife among school children in the country: children as young as 9 years old are involved in such activity, increasing their risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.7 A survey of family planning associations indicates that many would cut services if the shortfall from declining international funding is not found elsewhere.8 HIV/AIDS services are likely to be curtailed as part of these overall service cuts.

In the meantime, governments in the region are setting up national advisory councils and national commissions on AIDS as they try to curb the epidemic’s spread and impact. Caribbean Community (CARICOM) members have also agreed to adopt a regional approach to tackling HIV/AIDS, and discussions are afoot among member states about how this regional approach would be funded and implemented. The role of the family planning associations in this new approach is unclear at this stage, but it is hoped that they would be funded to continue work at the grassroots level since they have the potential to contribute significantly to any anti-AIDS efforts.

Conclusion

The Caribbean’s success in addressing population issues was achieved with a certain level of funding, without which the gains may be lost. The end of preferential trade status with the European Union, globalization, and trade liberalization, as well as fall out from the September 11 attacks on the United States (especially in relation to tourism) are adversely affecting revenues, and there can be no guarantee that the Caribbean countries will continue to maintain their current levels of income generation and economic growth. Some of the more developed countries in the region, such as Barbados, are technically in a recession (having recorded a third consecutive year of declining economic growth).9

The problem is exacerbated by competition from other sources of government expenditure, and it is most unlikely that many governments will be able to meet the shortfalls in international funding. The results could be devastating for the region in view of the emerging population issues and the need to sustain levels of success.

David Achanfuo Yeboah is senior fellow and inter-campus coordinator of the Special Studies and Research Methods Unit at the Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies, the University of the West Indies, in Cave Hill, Barbados.

References

- 1. D. A. Yeboah, “A Demographic Profile of the Caribbean,” CARICOM Perspectives, no. 70 (2001): 104-105.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Statistical Yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean (Santiago: ECLAC, 1999); and Yeboah, “A Demographic Profile of the Caribbean.”

- ECLAC, Statistical Yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean.

- D.A.Yeboah, “A Demographic Profile of the Caribbean.

- D.A. Yeboah, “Strategies Adopted by Caribbean Family Planning Associations to Address the Challenges of Declining International Funding,” International Family Planning Perspectives (forthcoming, June 2002).

- ECLAC, Statistical Yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean; and Yeboah, “A Demographic Profile of the Caribbean.”

- Barbados Ministry of Education, A Survey of Sexual Behaviour Among School Children (Bridgetown: Ministry of Education, 2001); and Ruben del Prado, United Nations Press Conference on AIDS, Port-of-Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, December 7, 2001.

- D. A. Yeboah, “Strategies Adopted by Caribbean Family Planning Associations to Address the Challenges of Declining International Funding.”

- “Third Year of Decline: Report of the Governor of the Barbados Central Bank,” Nation (Barbados), January 31, 2002.<.li>

Colombia Faces Prospects of More Population Displacement

Date

March 2, 2002

Author

Yvette Collymore

Former Senior Editor

Focus Area

Already one of the world’s major centers of displaced people, Colombia faces the likelihood that the latest escalation of a multifaceted civil war will force even more people from their homes and increase the risks of illness and death.

This country of some 43 million people that borders five countries — Venezuela, Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, and Panama — has endured nearly four decades of violence that has uprooted at least 2 million people and caused the deaths of some 30,000 others, according to the U.S. Committee for Refugees (USCR).

Forced migration often places women (especially pregnant women), children, the elderly, the disabled, and the chronically ill in situations of outright desperation. The New York-based Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children says the trauma and upheaval of war forces hundreds of thousands of Colombian women and their children from rural areas into the cities every year. In many cases, a woman will flee her village after a husband, brother, father, or son has been kidnapped or killed.

“Traumatized and terrorized, she will leave as quickly as possible — often within hours — for a hastily chosen destination. Upon arrival in that destination, she will be lucky to count on the help of a friend or relative for immediate temporary shelter,” says the Commission. “Just as likely, she will find no support whatsoever and will have to scramble to find a foothold in the barrios (slums) or at the edges of smaller towns.”

In its country reports on human rights released March 4, the U.S. State Department estimates that between 275,000 and 347,000 Colombians fled their homes in 2001 as a result of violence and instability in rural areas, with roughly one-quarter of these movements occurring in massive displacements. The report notes the difficulty in obtaining exact numbers of displaced people, however, since some are uprooted more than once, and many do not register with the government or other agencies. The World Health Organization (WHO) also reports that much of the displacement within Colombia occurs “silently,” with uprooted people simply merging unnoticed into their new situations.

Around the world, the number of internally displaced people — an estimated 20 million to 25 million — is higher than the estimated 14 million refugees who leave their countries, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Only two countries have more displaced nationals than Colombia (2 million): Sudan with 4 million and Angola with 2.3 million. Other countries with large displaced populations include Congo (1.8 million), Eritrea (1.1 million), and Afghanistan (956,600), according to UNHCR.

Like other refugees, internally displaced people leave their homes to avoid the effects of civil war, persecution, human rights abuses, drought, or other disasters. The USCR notes that displacement in Colombia is directly related to conflict, political violence, and human rights abuses. The conflict involves left-wing guerrillas, right-wing paramilitaries, and the Colombian armed forces.

In its report on human rights in Colombia in 2001, the U.S. State Department refers to a number of “serious problems” facing the Colombian people, including abuse of children; child prostitution; and widespread violence and extensive societal discrimination against women, indigenous people, and minorities.

Child labor is a nationwide problem as is trafficking in women and girls for the purpose of sexual exploitation, says the report. “Social cleansing” killings of street children, prostitutes, homosexuals, and others deemed socially undesirable by paramilitary groups, guerrillas, and vigilante groups also continue to be a major issue.

Unlike international refugees, internally displaced people have no special status and no specific legally binding instrument guarantees protection or assistance. Internally displaced populations are therefore highly vulnerable. Although primary responsibility for these people rests with national governments, they may get no public or other attention because governments may have little capacity or interest in assisting them. Often, they remain invisible or inaccessible.

People’s health status and health care are of vital concern in any crisis. The arrival of large numbers of people in a community can strain the health system, and the newcomers and residents also begin competing for access to food, potable water, shelter, and environmental resources. WHO notes that HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria are of paramount concern in situations of displacement and are difficult to address.

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) notes that though Colombia offers access to health care for all of its citizens, regulations require that each person be properly identified. Afraid of yet again becoming a target for armed groups in the civil war, Colombia’s displaced people generally avoid health care benefits. According to PAHO’s 2001 Country Health Profile for Colombia, only 22.1 percent of displaced households receive medical care.

PAHO says that a study conducted in Colombia between 1985 and 1994 highlighted a number of issues facing displaced people. The survey found that 6.7 percent of displaced households had lost a spouse or one child through violence before they migrated, and 1,570 orphans, abandoned children, or youth had to take responsibility for the family. Of the displaced population, 69.3 percent had their own homes before they were uprooted — a percentage that dropped to 28.7 percent after they moved. Before displacement, 40.7 percent were involved in agricultural production, either earning wages or as owners of small or medium-sized plots of land, and 10.0 percent had small or medium-sized businesses. Following displacement, 22.5 percent became street vendors, 12.9 percent became laborers, and only 10.7 percent continued to be engaged in agricultural activities.

Organizations working to improve the lives of Colombia’s displaced people recommend that the needs of children and women be made an urgent priority. They urge greater support for job training and loan programs that might enable women to improve their circumstances. For displaced children, access to education and to productive activities is key to fending off the many risks they face, including those of forced labor and sexual exploitation.

Colombia Facts and Figures

| Population, mid-2001 (millions) | 43.1 |

| Projected population, 2025 (millions) | 59.7 |

| Population 15-49 with HIV/AIDS, end-1999 (%) | 0.3 |

| Infant mortality rate (deaths per 1,000 live births by age 1) | 21 |

| Total fertility rate (average number of children per woman) | 2.6 |

| Married women 15-49 using modern contraception (%) | 63 |

| Population 16-20 currently attending school (%) | 42 |

| Households with a television (%) | 83 |

| Households with a telephone (%) | 52 |

| Households with a refrigerator (%) | 64 |

Source: 2001 World Population Data Sheet, Population Reference Bureau; Education and household statistics from Salud Sexual y Reproductiva en Colombia: Resultados, Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud 2000.

References

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), “Country Health Profile 2001: Colombia,” accessed at www.paho.org on March 6, 2002.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Internally Displaced Persons,” accessed at www.unhcr.ch, on March 6, 2002.

U.S. Committee for Refugees (USCR), “Principal Sources of Internally Displaced Persons,” accessed at www.refugees.org, on March 6, 2002.

Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children, “A Charade of Concern: The Abandonment of Colombia’s Forcibly Displaced,” accessed at www.womenscommission.org, on March 6, 2002.

World Bank, “Street Children in Central America: An Overview,” accessed at http://lnweb18.worldbank.org/External/lac/lac.nsf/

8ffa96b85a80b19d852567fb00738261/19e661ab7bbb25de852568cf006ad8a8?OpenDocument, on Jan. 22, 2002.

World Health Organization (WHO), “Internally Displaced Persons, Health and WHO,” paper presented at the Humanitarian Affairs Segment of ECOSOC 2000, New York, July 19-20, 2000, accessed at www.who.org, on March 6, 2002.

For More Information

See “Women, War, and HIV/AIDS: Judy Benjamin, of the Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children, Examines the Connections,” at www.prb.org.

">

">