Risk of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in the United States, Methodology

Product: Report

Author: PRB

Date: November 14, 2016

Summary of PRB Methods to Produce Estimates of Women and Girls Potentially at Risk of FGM/C in the United States

There are no national surveys or direct estimates of U.S. women and girls at risk of FGM/C, so estimates need to be derived through indirect means. Our methods follow the general procedures used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in their 1997 article on FGM/C in the United States.1 However, in consultation with CDC researchers, we modified those methods slightly to produce the 2013 estimates.

To produce the 2013 estimates, PRB first obtained the latest country-specific FGM/C prevalence rates from the Demographic and Health Surveys and other sources. Countries with FGM/C prevalence rates of at least 2 percent were included in the analysis. We then used the Census Bureau’s 2013 American Community Survey (ACS) Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) to obtain numbers of women in the United States (total, under age 18, and 18 and older) with ties to one of the countries where the FGM/C prevalence rate was at least 2 percent. We define “country ties” as meeting at least one of the following criteria: (a) Persons who were born in a high-FGM/C prevalence country; and (b) Persons under age 30 who are residing with a parent who was born in a high FGM/C prevalence country. Also included in the estimates were women listing their birthplace (and children listing their residential parents’ birthplace) as Eastern Africa, Western Africa, Northern Africa, Western Asia, or “Africa”—if the country was not specified. (“Middle Africa, not specified” is not included as a separate category in the ACS PUMS).

PRB calculated the population of women and girls who had undergone FGM/C or were potentially at risk of FGM/C in the United States by applying country-specific FGM/C prevalence rates for women ages 15 to 19 to U.S. women under age 20, and rates for women ages 15 to 49 to U.S. women ages 20 and over.

For regions such as “Northern Africa, not specified,” we estimated the FGM/C prevalence rate by estimating the female population ages 15 to 19 and 15 to 49 of each country in the region—using the 2010 population estimates from the UN Population Division—and multiplying it by that country’s age-specific FGM/C prevalence rates. (Countries where the FGM/C prevalence rate was not listed were counted as having a rate of 0). We then divided each region’s “at risk” population by its total to obtain each region’s FGM/C rate.

We then applied the “weighted average” (i.e., the region’s collective FGM/C prevalence rate) to the ACS population in each region. This calculation yielded an estimate of the “at risk” population for each region. We applied the “weighted average” for women ages 15 to 49 to the ACS population of women ages 20 and over; and the average for women ages 15 to 19 to the ACS population of women under age 20. (Note: If a region’s collective FGM/C prevalence rate was less than 2 percent, then those regional data from the ACS were excluded from both the total and the “at-risk” populations.)

References

1 W.K. Jones et al., “Female Genital Mutilation. Female Circumcision. Who is at Risk in the U.S.?” Public Health Reports 112, no. 5 (1997): 368–77.

Women and Girls at Risk of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in the United States

Date

February 5, 2016

Authors

Mark Mather

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

Charlotte Feldman-Jacobs

Former Associate Vice President, International Programs

Focus Areas

A new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report on female genital mutilation/cutting in the United States was released in January 2016, providing additional information on women and girls at risk.

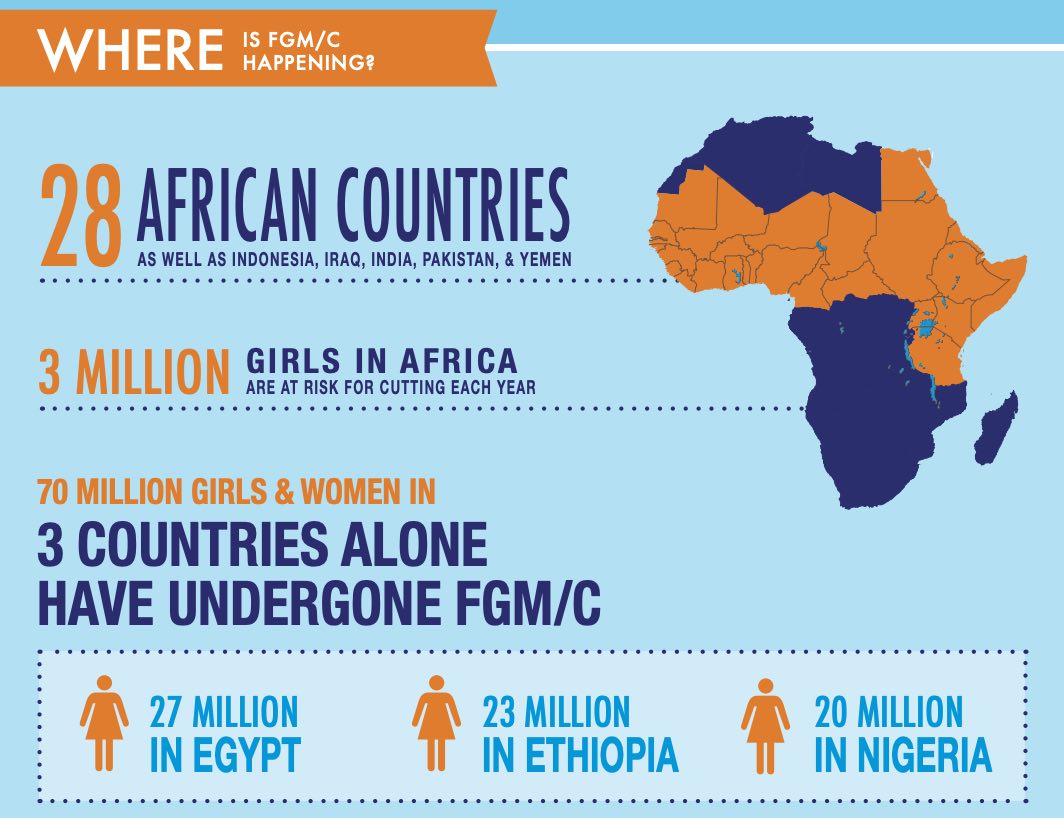

Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), involving partial or total removal of the external genitals of girls and women for religious, cultural, or other nonmedical reasons, has devastating immediate and long-term health and social effects, especially related to childbirth. This type of violence against women violates women’s human rights. There are more than 3 million girls, the majority in sub-Saharan Africa, who are at risk of cutting/mutilation each year. In Djibouti, Guinea, and Somalia, nine in 10 girls ages 15 to 19 have been subjected to FGM/C. Some countries in Africa have recently outlawed the practice, including Guinea-Bissau, but progress in eliminating the harmful traditional practice has been slow.1 Although FGM/C is most prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, global migration patterns have increased the risk of FGM/C among women and girls living in developed countries, including the United States.

Increasingly, policymakers, NGOs, and community leaders are speaking out against this harmful traditional practice. As more information becomes available about the practice, it is clear that FGM/C needs to be unmasked and challenged around the world.

The U.S. Congress passed a law in 1996 making it illegal to perform FGM/C and 23 states have laws against the practice.2 Despite decades of work in the United States and globally to prevent FGM/C, it remains a significant harmful tradition for millions of girls and women. In the last few years, renewed efforts to protect girls from undergoing this procedure globally and in immigrant populations have resulted in policy successes. In Great Britain and in other European countries, a groundswell of attention has focused on eradicating the practice among the large immigrant populations of girls and women who have been cut or are at risk of being cut. Moreover, in 2012 the 67th session of the UN General Assembly passed a resolution urging states to condemn all harmful practices that affect women and girls, especially FGM/C. The UN resolution was a significant step toward ending the practice around the world.

In the United States, efforts to stop families from sending their daughters to their home countries to be cut led to a 2013 law making it illegal to knowingly transport a girl out of the United States for the purpose of cutting. FGM/C has gained attention in the United States in part because of the rising number of immigrants from countries where FGM/C is prevalent, especially sub-Saharan Africa. Between 2000 and 2013, the foreign-born population from Africa more than doubled, from 881,000 to 1.8 million.3

The Risk of FGM/C in the United States

In 2013, there were up to 507,000 U.S. women and girls who had undergone FGM/C or were at risk of the procedure, according to PRB’s data analysis. This figure is more than twice the number of women and girls estimated to be at risk in 2000 (228,000).4 The rapid increase in women and girls at risk reflects an increase in immigration to the United States, rather than an increase in the share of women and girls at risk of being cut. The estimated U.S. population at risk of FGM/C is calculated by applying country- and age-specific FGM/C prevalence rates to the number of U.S. women and girls with ties to those countries. A detailed description of PRB’s methods to estimate women and girls at risk of FGM/C is available.

Just three sending countries—Egypt, Ethiopia, and Somalia—accounted for 55 percent of all U.S. women and girls at risk in 2013 (see Table 1). These three countries stand out because they have a combination of high FGM/C prevalence rates and a relatively large number of immigrants to the United States. The FGM/C prevalence rate for women and girls ages 15 to 49 is 91 percent in Egypt, 74 percent in Ethiopia, and 98 percent in Somalia. About 97 percent of U.S. women and girls at risk were from African countries, while just 3 percent were from Asia (Iraq and Yemen).

Table 1

U.S. Women and Girls Potentially at Risk for FGM/C, 2013 Data

Top 10 Countries of Origin

| U.S. Women and Girls at Risk of FGM/C | |

|---|---|

| All Countries of Origin | 506,795 |

| Egypt | 109,205 |

| Ethiopia | 91,768 |

| Somalia | 75,537 |

| Nigeria | 40,932 |

| Liberia | 27,289 |

| Sierra Leone | 25,372 |

| Sudan | 20,455 |

| Kenya | 18,475 |

| Eritrea | 17,478 |

| Guinea | 10,302 |

| Other Countries of Origin | 69,981 |

Source: Population Reference Bureau. Estimates are subject to both sampling and nonsampling error.

Girls under age 18 made up one-third of all females at risk of FGM/C in 2013. While some of these girls were born in countries with high prevalence rates, the majority are U.S.-born children of parents from high-prevalence countries. Anecdotal reports tell of U.S.-born girls being cut while on vacation in their parents’ countries of origin and of people traveling to the United States to perform FGM/C on girls here.5

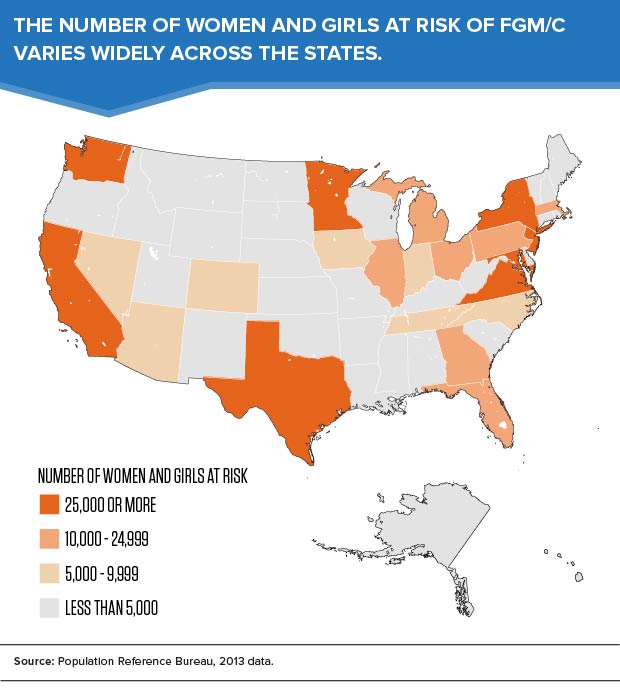

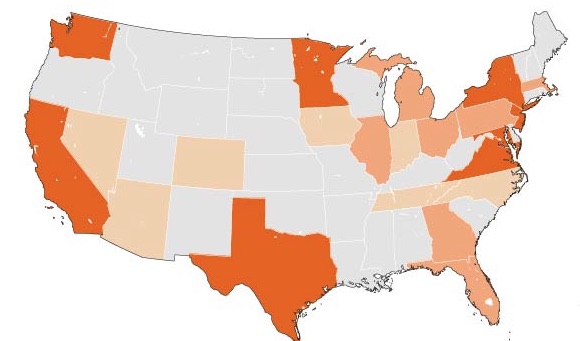

The number of women and girls at risk varies widely across different states (see map). In 2013, about three-fifths of all women and girls at risk of FGM/C lived in eight states: California, Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Texas, Virginia, and Washington. California had the largest at-risk population (57,000), followed by New York (48,000), and Minnesota (44,000). Minnesota has a disproportionate number of women and girls at risk of FGM/C because of its large Somali immigrant population, estimated at more than 31,000 in 2013. See the number of women and girls at risk in each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

While the population at risk is still highly concentrated in large “gateway” states, many immigrant families have fanned out from traditional immigrant gateways to new destinations around the country. Some states also receive large numbers of African refugees. In fiscal year 2014, one-fourth of the 70,000 refugees arriving in the United States were from Africa.6

Most women and girls at risk of FGM/C are living in cities or suburbs of large metropolitan areas. In 2013, 40 percent of the population at risk lived in five metro areas: New York, Washington, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Los Angeles, and Seattle (see Table 2). See a list of the 50 metropolitan areas with the largest at-risk populations.

Table 2

U.S. Women and Girls Potentially at Risk for FGM/C, by Metro Area, 2013 Data

Top 10 Metropolitan Areas

| U.S. Women and Girls at Risk of FGM/C | |

|---|---|

| All Areas | 506,795 |

| New York-Newark-Jersey City, NY-NJ-PA | 65,893 |

| Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV | 51,411 |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI | 37,417 |

| Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA | 23,216 |

| Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, WA | 22,923 |

| Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Roswell, GA | 19,075 |

| Columbus, OH | 18,154 |

| Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD | 16,417 |

| Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX | 15,854 |

| Boston-Cambridge-Newton, MA-NH | 11,347 |

| Other Metro Areas | 216,307 |

| Outside of Metro Areas | 8,780 |

Source: Population Reference Bureau. Estimates are subject to both sampling and nonsampling error.

Looking Ahead

With the rise in international migration, the lines between issues facing women and girls in the U.S. and developing countries are blurred. Although FGM/C prevalence rates have held steady or declined in many African countries in recent years, the number of women and girls at risk of FGM/C in the United States is expected to increase in the future, as the foreign-born population from Africa increases.

Given the rapid growth of the youth population in developing countries, improving the well-being of girls has become a priority for many international organizations that promote gender equality and higher standards of living across the globe. Ending harmful practices against women and girls in developing countries could have a measurable impact on the well-being of immigrant families around the world.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Kelvin Pollard and Donna Clifton at PRB for their assistance with the data analysis, and Howard Goldberg and Paul Stupp of CDC for their collaboration on the methodology. We are grateful to the Wallace Global Fund for providing funding for PRB’s work on this topic.

References

- Donna Clifton and Charlotte Feldman-Jacobs, “International Day of Zero Tolerance to Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting Marks Ninth Year” (2012) accessed at www.prb.org/Articles/2012/fgm-zero-tolerance-2012.aspx, on Feb. 2, 2015.

- Equality Now, “Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) in the United States,” accessed at www.equalitynow.org/sites/default/files/EN_FAQ_FGM_in_US.pdf, on Feb. 2, 2015.

- Migration Policy Institute, Data Hub, accessed at www.migrationpolicy.org/data/state-profiles/state/demographics/US, on Jan. 15, 2015.

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital, “Female Genital Cutting Research,” accessed at www.brighamandwomens.org/Departments_and_Services/obgyn/services/africanwomenscenter/research.aspx, on Feb. 2, 2015. Estimates for 2000 were based on a slightly different methodology and are not strictly comparable with the 2013 data. However, the large increase in the number of women and girls at risk of FGM/C is not surprising, given rising levels of immigration from sub-Saharan African countries since 2000.

- Equality Now, “Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) in the United States.”

- U.S. Department of State, “Refugee Arrivals,” accessed at www.wrapsnet.org/Reports/Archives/tabid/215/Default.aspx, on Feb. 2, 2015

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: Data and Trends Update 2014 - Infographic

Product: Infographic

Author: PRB

Date: February 5, 2014

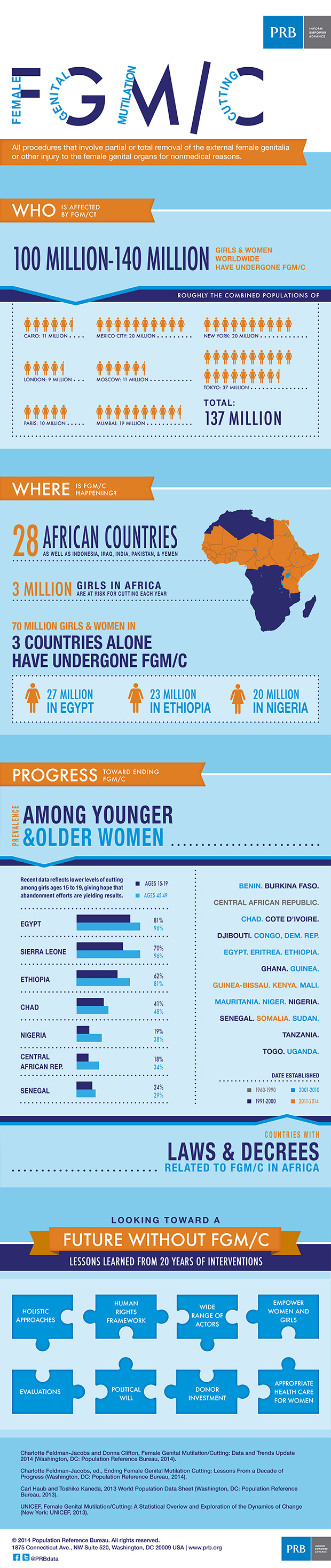

(February 2014) This infographic highlights key data and trends from PRB’s datasheet, Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: Data and Trends Update 2014. The infographic explains what female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) is; who is affected by the practice; where the practice is still present; progress toward ending FGM/C; and lessons learned from 20 years of interventions.

Ending Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: Lessons From a Decade of Progress

Date

February 3, 2014

Author

PRB

(February 2014) Over the last 20 years, significant efforts have been made at the community, national, and international levels to address the issue of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C). Numerous international and national policy statements have called for an end to FGM/C, which has been recognized as a violation of girls’ and women’s human rights and an obstacle to gender equality. Program planners have implemented countless interventions to educate and empower communities to abandon the practice. Researchers have conducted important studies and evaluations have contributed to a better understanding of the prevalence of the practice and the types of procedures carried out, as well as the reasons communities continue to practice it. Research and experience have begun to lift the veil on the intended and unintended impacts of many of the strategies undertaken over the years.

The PRB report, Ending Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: Lessons From a Decade of Progress, pulls together the lessons learned from the last decade and crafts a roadmap for how to strengthen future programs to end the practice. By looking back, policymakers and advocates will be better able to move forward decisively to create the conditions necessary to allow women and girls around the world to achieve their full potential.

In the first decade of this century progress has been made toward abandonment. Studies have looked at the physical, emotional, and mental impacts of FGM/C. Research has deepened our understanding of the diverse reasons for the continuation of the practice, providing a framework for theories about the origins and social dynamics that lead to its perpetuation. Reflecting the work of dedicated advocates, today most practicing countries have passed laws banning the practice, and prevalence is beginning to decline in some countries.

In September 2000, USAID officially incorporated elimination of FGM/C into its development agenda and created the official U.S. government policy toward FGM/C.

In 2002, the Donors Working Group on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting formed to convene key international actors, including representatives of UN agencies, European donors, private funders, and USAID.

In February 2003, the Inter-African Committee (IAC) on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children held its landmark conference in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Many first ladies of Africa, led by the first lady of Nigeria, officially declared “Zero Tolerance to FGM” to be commemorated every year on Feb. 6. Drawing from this energy, UNICEF’s Innocenti Research Centre organized a consultation in 2004, resulting in a seminal publication, Changing A Harmful Social Convention: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting.

In 2008, the Donors Working Group produced A Platform for Action Toward the Abandonment of FGM/C. That same year UNFPA and UNICEF formed a strategic partnership known as the UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on FGM/C’s “Accelerating Change.” They have been working together, in headquarters and field offices, to develop, fund, and implement policies and programs to accelerate abandonment of FGM/C. The results of this program should inform the work of programs and governments for years to come.

In 2012, the 67th session of the United Nation’s General Assembly passed a wide-reaching resolution urging states to condemn all harmful practices that affect women and girls, in particular female genital mutilation, giving the work during this decade a powerful boost forward.

As stated by Berhane Ras-Work, founding president of the IAC and one of 12 experts on FGM/C who were interviewed for this report, “The future is bright. Success has been premised on strengthening conviction, not on using force.”

Our vision of the way forward has been sharpened by all the work that has been conducted over the years. As we have now passed a dozen anniversaries of Zero Tolerance Day, it is an opportune time to reflect and build on three key maxims that stand strong:

- First, the centrality of social norms—what communities believe and how they act and expect the members of that community to act—must be addressed.

- Second, a wide range of actors play pivotal roles in the abandonment of FGM/C—men, women, grandmothers, boys, girls, and community, religious, and political leaders.

- Third, not every approach will work in every place, every village, every tribe. But if the approach is too narrow and siloed it will not work anywhere. The focus must be on holistic, integrated, multisectoral approaches that bring together the advocacy, policy-level work, and community-level transformation of social norms.

In the next decade those seeking the end of FGM/C will have to meet some of the same challenges not addressed in the last decade, including:

- Wider support from donors, including recipient governments and organizations.

- Better evaluation of approaches that have been used to date.

- A closer look at how decisionmaking around FGM/C occurs.

- Commitments from the wider gender community to embrace FGM/C as an issue needing attention.

- Responsible health care for women who have been cut.

Charlotte Feldman-Jacobs is program director, Gender, at the Population Reference Bureau.

Female Genital Cutting: Current Status and Trends

Date

February 16, 2007

Author

PRB

(February 2007) Although many governments have passed laws against female genital cutting, the practice is still widespread in many countries. More than seven in 10 women have undergone the procedure in Mauritania, Ethiopia, Burkina Faso, Northern Sudan, Eritrea, Mali, Egypt, and Guinea. In some of the countries where the practice is extremely common—Eritrea and Sudan, for example—a substantial proportion of women are subjected to infibulation, the most extreme form of cutting. In other countries, fewer than half of women undergo the procedure and the practice is confined to only some regions.

In the majority of countries where two surveys have been conducted, prevalence has decreased somewhat. In Egypt, the practice remains almost universal, despite the government’s pledge during the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development, which was held in Cairo, to abolish female genital cutting.

In most countries, traditional practitioners perform the procedure. In some countries, however, medical personnel such as doctors, nurses, and midwives also perform genital cutting procedures. The practice of the “medicalization” of FGC appears to be increasing in at least two countries where data is available: In Egypt, where medical personnel performed 75 percent of these procedures in 2005, compared with 61 percent in 2000 and 55 percent in 1995; and in Nigeria, where the practice increased from 13 percent in 1999 to 27 percent in 2003.

These data are drawn from: P. Stanley Yoder, Noureddine Abderrahim, and Arlinda Zhuzhuni, Female Genital Cutting in Demograhpic and Health Surveys: A Critical and Comparative Inquiry (Calverton, MD: ORC Macro, 2004); and from other recent DHS estimates.

The Campaign Against Female Genital Cutting: New Hope, New Challenges

Date

February 16, 2007

Author

PRB

(February 2007) Despite the decades-long worldwide campaign against female genital cutting, more than 3 million girls a year still undergo this harmful traditional practice. But speakers at a symposium in Washington this month said they hoped that recently published social science and health research could have a major impact in persuading communities to abandon the custom.

There are increasing numbers of good studies about which kinds of programs have promise in persuading communities to abandon cutting. At the same time, recent medical research provides new evidence that females who are cut are more likely to have complicated births and stillbirths.

The Feb. 6 symposium, attended by dozens of researchers, advocates and government officials, was sponsored by the U.S. Agency for International Development and organized by the Population Reference Bureau. It was held on the fourth International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Cutting, a day first proclaimed by the first lady of Nigeria on behalf of all the African first ladies.

Banned Worldwide, Cutting Still Is Widely Practiced

Female genital cutting, also known as female genital mutilation or female circumcision, has been banned in many countries over the last decade as a violation of human rights. It persists as a local custom in at least 26 developing countries, and many people believe, mistakenly, that it not only is a religious requirement, but that it makes a girl clean and sexually modest. More than 130 million women have been cut, mainly in Africa. The practice ranges from a nick on the clitoris to surgical removal of the entire outer genital area, which is then stitched up. Some girls have bled to death, and others suffer long-term medical and psychological complications.

Genital cutting has become less common in many countries, according to surveys, but remains almost universal in others, including Egypt, whose government pledged in 1994 to abolish it.

The rise in immigration to the United States and other developed nations from places where cutting is practiced has raised fears that it could become more common in destination countries. Last year, an Ethiopian immigrant to the United States was sentenced to prison in Georgia for cutting his infant daughter. “We’ve got to figure out a way to address it in our backyard, not just far away,” Kent Hill, assistant administrator of USAID’s Bureau for Global Health, told the symposium.

Research Points to Common Factors in Promising Programs

One lesson that researchers have drawn is that although world opinion condemns cutting as a violation of human rights, framing it that way may not be the most effective local tool. Campaigns that focus only on the harm of cutting to a girl’s health may present other risks, in part because that message may contribute to “medicalizing” the procedure—that is, encourage parents to have their daughters cut by medical professionals rather than traditional practitioners.

One new development is that some groups are enlisting help from religious leaders in trying to persuade communities to abandon the practice of female circumcision. Two speakers from Kenya—Maryam Sheikh Abdi, a program officer with the Population Council, and Ibrahim Asmani, an advocate and Islamic scholar—talked about how to counter arguments that being cut is a requirement to be a good Muslim woman. But obstacles include the low priority given women’s issues in some communities and the lack of scholarly consensus, they said.

The most effective programs, researchers agree, are community-based, account for differing local customs, and use respected local leaders to get the message across. “Change is not possible from the outside,” said John Townsend of the Population Council, who summed up the day’s presentations. “It requires an internal process.”

The most commonly cited success story is a program developed by the nonprofit group Tostan (a word that means “breakthrough” in the Wolof language) that began in Senegal and expanded to six other African countries. The group’s “community empowerment program” does not talk about cutting in isolation, but also provides lessons on other topics such as problem-solving, hygiene, and human rights.

Nafissatou Diop, a program associate with the Population Council, also cited the success of a tough law in Burkina Faso that incorporates free phone calls for reporting violations, extensive public-service advertising on radio and television, and the involvement of 13 government ministries. Diop, who is based in Senegal, said one common factor in both Burkina Faso and Senegal was use of comprehensive, well-structured holistic intervention, coupled with decentralized, locally controlled programs.

Researchers Encounter Some False Answers

Another program, operated by the Navrongo Health Research Center in northern Ghana, included the topic of cutting in a series of lessons about reproductive health and cultural expectations of women. The program, known for its scientifically rigorous evaluation, also included training in livelihood and life skills, from crafts production to bookkeeping. Its evaluation found that the education program alone, or education combined with livelihood and life skills, was more effective than skills training alone, but program officials believe skills training may be an “entry point” to encourage girls to join.

Reshma Naik, principal investigator in the Navrongo evaluation, said evaluators learned that some girls who had been cut told researchers they had not been. It may be that girls are worried about being arrested for violating the law, she said, or perhaps they were trying to tell interviewers what they wanted to hear. Evaluators must find other ways to ask the question, she said, and be cautious in reporting data.

Medical Consequences Are More Severe Than Previously Documented

It has long been known that cutting harms the health of girls. But a World Health Organization study published last year inThe Lancet concluded that it also affects childbirth, providing the first evidence of obstetric complications linked to female genital cutting.

The study, based on a sample of more than 28,000 women in six African countries, found that mothers with more extreme forms of cutting were more likely to have complications. Cutting also was associated with 10-20 additional stillbirths per 1,000 live births.

Hill, of USAID, described the study’s conclusions as “landmark findings.”

Yet, according to Hermione Lovel, a British health official who was a member of the WHO study group, medical students know little about the practice of female genital cutting, including its potential complications. It is not included in medical school training, she said, but should be.

Summing Up: The Needs of Women and Girls Must Be Central

A key lesson from the symposium, said Townsend in his wrap-up presentation, is that no technique will work by itself in reducing this long-time custom. Human rights, laws, religious scholars, cultural leaders and the media all have a role. Ethical issues, such as the propriety of interviewing girls under 10, must be considered. And he said organizations should focus more sharply on promising programs—and turn away from what is known to fail, such as simply retraining traditional practitioners to do other work.

But at the center of the campaign, he said, must be the needs of women and girls. Do not stigmatize those who have been cut, he said; rather, support the example of “positive deviance” set by those who challenge cultural norms and resist being cut.

“The larger issue of women’s equality,” he said, “is critical to anything we do.”

D’Vera Cohn is a senior editor at the Population Reference Bureau.

Abandoning Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: An In-Depth Look at Promising Practices

Products: Report, Event Presentations

Author: PRB

Date: February 15, 2007

Symposium: International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Cutting

4th Anniversary, February 6, 2007

Washington, DC

(February 2007) This symposium was sponsored by the United States Agency for International Development’s Bureau for Global Health. The proceedings were organized by the Population Reference Bureau.

Below is the agenda for the symposium, along with selected presenters’ PowerPoint presentations. We have also included bios for the presenters (DOC: 45KB) as well as Minutes from the Symposium (DOC: 63KB).

THEME: Broadening the Base, Renewing the Agenda

Welcome, by Kent Hill, Assistant Administrator, Bureau for Global Health, USAID

Panel 1: Promising Practices: Evaluation Methods and Results

Moderator: Sarah Harbison, USAID

Panelists:

P. Stanley Yoder, Senior Qualitative Research Specialist, Macro International, Methodological Challenges for the Evaluation of FGC Programs (PPT: 414KB)

Nafissatou Diop, Program Associate II, Population Council/Senegal, What Makes Communities Abandon Female Genital Mutilation: Experiences from Senegal and BurkinaFaso (PPT: 830KB)

Reshma Naik, Principal Investigator, The Navrongo FGC Trial: Impact and Lessons Learned (PPT: 373KB)

Panel 2: Change Makers

Moderator: Adisa Douglas, Public Welfare Foundation

Panelists:

Maryam Sheikh Abdi, Program Officer, Population Council/Kenya and Ibrahim Asmani, Advocate and Islamic Scholar, A Religious-Oriented Approach To Addressing FGM/C (PPT: 184KB)

Claire Houngan Ayemonna, Magistrate, Benin, Promoting the Abandonment of FGC in Benin: Strategies and Results (PPT: 730KB)

Florence Machio, Journalist and Regional Coordinator, Africawoman, Working with the Media

Rachel Sandel Morse, Harvard Law School, Protecting Girls from FGM: Challenges and Opportunities for Legal Intervention in Africa (PPT: 356KB)

Panel 3: Widening the Circle: The Next 10 Years

Moderator: Sarah Craven, UNFPA

Panelists:

Bettina Shell-Duncan, Associate Professor of Anthropology and Health Services, University of Washington, Framing FGM: Health and Human Rights Approaches (PPT: 67KB)

Leah Freij, Senior Technical Advisor for Gender, CEDPA, Changing Youths’ Attitudes Toward FGM in Egypt (PPT: 873KB)

Hermione Lovel, Department of Health, Cambridge, United Kingdom, FGC and Obstetric Complications: Results of the WHO Study (PPT: 825KB)

Summation/Wrap-up: John Townsend, Population Council

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">