Jeffrey Jordan

Former President and CEO

This article was originally posted on New Security Beat. It is reposted here with their permission.

Featured side by side at the top of The New York Times home page recently were two stories: one on the United States and China, the world’s largest producers of carbon emissions, committing to a global climate agreement, another on how rising seas are already affecting coastal communities in the United States.

The stories reflected the immediacy of global environmental challenges – climate change being the predominant one among many. These challenges were the impetus for the Population Reference Bureau (PRB) to focus on “human needs and sustainable resources” in this year’s World Population Data Sheet, a widely used print and digital resource for the latest demographic, health, and environment data from around the world. As in years past, the Data Sheet features our latest global population projections, but there are additional indicators in the 2016 edition that underline the challenge of balancing sustainability with a growing population.

First, the population picture: Despite an overall decline in fertility rates, our projections this year point to a world with 9.9 billion people at mid-century, about one third more than we have today. Devotees of our annual Data Sheet may notice that our 2050 forecast has been inching up over recent years. The principal reason has been slower than anticipated rates of fertility decline in many sub-Saharan African countries. The top 10 country fertility rates in the world are all in Africa, led by Niger with an average of 7.6 lifetime births per woman. Niger’s population is on track to more than triple by 2050.

Drilling down, population trends vary widely by region. Under our assumptions, Africa’s population will more than double by mid-century, gaining 1.3 billion people. Compare this to a projected gain of nearly 900 million in Asia, by far the most populous region today, and only 223 million in the Americas. Europe (including all of Russia) is actually expected to decline by 12 million people. Africa alone will account for more than half (54 percent) of the total projected population increase by 2050, while Asia will kick in 34 percent. The combined population of the 48 “least developed countries” as defined by the United Nations will double.

The global population increase is likely to come despite lower fertility rates on the whole. Rapid increases in world population over the last several decades have yielded a large number of people of childbearing age, creating what’s called “population momentum.” Most countries will continue to grow for many years even though their fertility has declined or is in the process of doing so. Thus, barring a dramatic and unprecedented decrease in fertility rates in the next few decades – particularly in Africa – the world will inevitably have billions more people.

Regional population growth disparities also relate to the global immigration challenge that is currently roiling Europe (though it is by no means confined to that part of the world). The combination of growing population and environmental pressures as well as political upheaval in certain countries and regions will inevitably prompt more people to seek better lives elsewhere. Migration statistics are notoriously unreliable, given the difficulties of tracking undocumented movements and variations in what defines a migrant. However, this year’s Data Sheet indicates that Africa has the most out-migration in relation to the size of its population, while Europe is absorbing the most migrants proportionately.

Future migration patterns may also play an important role in determining prospective population sizes of both sending and receiving countries and regions. Germany, for example, experienced the highest net migration of foreigners in its post-war history last year, at slightly more than 1 million people. For the first time, migrants from outside Europe made up the majority of Germany’s immigrants. While the region is projected to start losing population in coming decades, migration could be a significant wild card in this outcome.

From an environmental and resource perspective, the world also faces stark regional differences. In the Data Sheet, we focused on presenting indicators with reliable data that give a broad view of how population, health, and environmental factors interact.

Generally speaking, reliable environmental and resource data are hard to obtain, often because collecting such data has been a lower priority for many countries that already have data collection challenges, or because such data transcend borders and regions, requiring a more global collection approach. In some cases, such as measuring net changes in tree cover, technical obstacles preclude accurate counts for a sufficient number of countries for inclusion in the Data Sheet.

Global carbon emissions figures, compiled by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, were up 60 percent between 1992 and 2013 (the latest year for which reliable data are available), to 9.8 billion metric tons. A large chunk of that increase came from less developed countries, particularly China, whose total emissions rose nearly fourfold to 2.8 billion metric tons. India’s total emissions increased nearly 300 percent to 555 million metric tons.

Europe’s total emissions actually decreased over this period by 17 percent to 1.56 billion metric tons, while emissions in Canada and the United States only rose about 5 percent to 1.54 billion metric tons. Overall, 43 countries were estimated to have reduced their carbon emissions from 1992 to 2013, including notable reductions in high-income countries such as Germany and the United Kingdom. These trends and the global climate deal bring reasons for optimism about lowering future emissions levels.

Energy use is a key component of carbon emissions, and we figured that the share of energy consumption from renewable resources would help gauge how close the globe is to reducing dependency on heavily polluting fossil fuels. Note that “renewables” is a nuanced category; while it includes things like solar and wind power, it also includes hydropower, which is sometimes linked to serious environmental issues, and solid biofuels, which can include pretty much anything people burn for fuel, such as trees and bushes. As a result, many low-income countries have high renewable shares, such as Sierra Leone at 80 percent, while industrialized countries come in on the low side (eight percent for the United States). Worldwide, renewables account for 18 percent of energy consumption, according to data compiled from the International Energy Agency and World Bank.

In our rapidly urbanizing world, we also thought it was important to highlight trends related to resource use that affect public health. In the Insights section of our digital Data Sheet, we show how increasing urbanization and industrialization in developing countries has led to higher concentrations of fine particulate matter that can lodge in people’s lungs and cause asthma and other serious health problems. Middle-income countries face the biggest challenge as their industrialization process moves more quickly than their ability to manage pollution.

The global income divide comes to the fore again in a great set of data on municipal waste volumes compiled by a dedicated team of researchers running the Wasteaware data project. Municipal waste is a massive and growing public health and environmental problem, particularly in low-income countries where toxins from large numbers of uncontrolled dumpsites end up in water tables and in the air through unsorted refuse burning. While waste volumes (measured in kilograms per capita per year) tend to rise in tandem with national incomes, wealthier cities logically have more resources to devote to controlled disposal and household waste collection.

The municipal waste data underline that population numbers are not the whole issue when it comes to resource use and sustainability. In principle, having more people means resources must be managed more soundly, and funds made available to do so. Even so, many more billions of people will surely strain the planet’s ability to sustain us.

The mid-century population projection is by no means certain, but it is a warning that needs to be heeded. Is it possible to support a population of 10 billion? We hope to be prepared to answer that question.

Explore the digital 2016 World Population Data Sheet for access to more maps, data, and insights, or download the PDF.

Sources: International Energy Agency, The New York Times, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Population Reference Bureau, Wasteaware, World Bank.

Farzaneh Roudi recently retired after nearly three decades with Population Reference Bureau (PRB). She started PRB’s Middle East and North Africa (MENA) program in 2001 through a partnership with the Ford Foundation office in Cairo. Roudi, who earned a bachelor’s degree in Sociology in Iran and a master’s degree in Demography from Georgetown University, is well known in the MENA region and beyond for her passion and dedication to expanding knowledge and generating policy discussion about population and gender issues. We asked her about her experiences working in the MENA region and her reflections on current trends.

Q: How did PRB’s MENA program get off the ground?

My first trips to the region on behalf of PRB were in 1993 when I attended a couple of regional conferences held in preparation for the United Nations International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) and in 1994 when I attended the ICPD in Cairo. What I learned early on from my interactions with people in the region was that while they had high regard for PRB publications, they wanted them tailored to their cultural sensitivities. Peter Donaldson, PRB’s president at the time, supported my idea of initiating a MENA program. We were able to get our idea off the ground and sustain it over the years with generous support from the Ford Foundation office in Cairo.

Q: You have spent many years working on population, reproductive health, and gender issues in the MENA region. Compared to when you started this work, what level of progress do you see on the ground?

Progress in openness to address and deal with population and reproductive health issues has been significant throughout the region. This openness came about in large part because of two things that happened at the international level. One was ICPD’s Programme of Action that for the first time put women’s reproductive health high on the policy agenda for global development and the other was the HIV pandemic spreading to the region. HIV and AIDS helped break taboos about reproductive health being part of public policy discourse and the Programme of Action provided a comprehensive framework for such policy discussion and action. In particular, ICPD put to rest the debate regarding the legitimacy of states’ roles in the private affairs of families by providing family planning services to help women avoid unintended pregnancies.

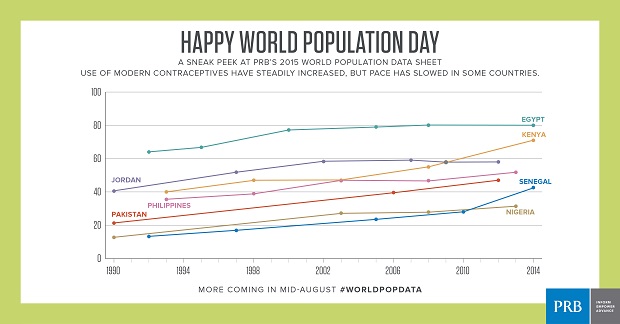

Today, the majority of married women of reproductive age in most MENA countries practice family planning, using modern or traditional methods. Around 60 percent of women in Egypt, Iran, and Tunisia use modern family planning methods. And in Yemen, the least developed country in MENA, about 25 percent of women use modern methods, a significant increase from 10 percent in the late 1990s. Fertility has declined in every country over the past 30 years. A number of them have completed their demographic transition. In Bahrain, Lebanon, Iran, Tunisia, and Turkey, fertility rates are now around 2 births per woman. In Yemen, where the risk of maternal death is highest, fertility has declined from an average of 6.5 children to 4.4 children per woman over the past 20 years. Fertility decline in Egypt, the most populous country in the region, however, has stalled in recent years, even taking a bit of a U-turn to reach 3.5 births per woman—the same rate as it was 15 or 20 years ago.

On gender, improvement in girls’ education has also been significant. In a number of countries, there are more female than male students enrolled in universities. As a result, the number of educated women entering the job market has been increasing significantly. The unemployment rate among these women is higher than their male counterparts despite the fact that MENA has the lowest rate of female labor force participation among world’s major regions. The region’s cultures, which tend to limit women’s mobility in public places, are often blamed for women’s low labor force participation. Another factor is that many economies in the region are overshadowed by the oil industry that is male dominated, helping reinforce patriarchal attitudes.

Many women’s organizations across the region have been active in helping remove social and legal barriers to women’s economic participation and improve their life in general. Discrimination against women is a global issue. It exists in countries around the world in varying degrees. Except for Tunisia and Turkey, what distinguishes MENA countries from most other countries in the world is that discrimination against women is often codified in laws, especially the family law. But, there have been successes in modifying family laws in some countries, such as Lebanon and Egypt, to give women the right to pass on their citizenship to their children when the father is a foreigner, for example. Morocco completely rewrote its family law, giving equal rights to men and women in marriage, divorce, and custody of their children. Making family laws more egalitarian is necessary to change the region’s patriarchal culture. Altering gender relations within families is essential to spark democracy and progress in MENA.

Q: The region has seen dramatic political changes since the Arab uprisings known as the Arab Spring. In what ways has this affected efforts to improve the condition of women and children?

The improvements have been on paper so far, if any. The new political actors in Egypt, for example, have adopted a new constitution, and women’s organizations were involved to ensure that women’s and children’s rights were protected—undoubtedly, an important step in the right direction, but a lot more needs to happen before this shift can turn into anything tangible. First, girls and women should know about and understand their rights under the new constitution and be empowered to act when their rights are violated. Second, the whole judiciary and law enforcement system must step up to enforce the laws.

The point to remember is that no issue specific to women was in the original demands of the demonstrators in the first place. I remember in the first days of the Egyptian uprising, Peter Donaldson (then head of the Population Council) organized a conference call and had Ragui Assaad, an expert in Egyptian affairs and the director of the Council office in Cairo, on the call to give an analysis of the situation on the ground. I asked if any women’s issues were included in the demands of people on the street, and he said no. So, I don’t find it logical when I see references to Arab Spring’s failure in changing women’s life this way or that way. Among so many slogans shouted on streets in Tunis, Cairo, or any other cities, there was none specific to women.

The Arab Spring does not seem to have generally changed people’s lives for the better. Many economies have deteriorated since and some of the uprisings have turned into civil conflicts. As a result, there are a large and growing number of women and children who are affected by the conflicts, requiring special protection because of their vulnerability to abuse and gender-based violence.

Q: Is there a role for the international community in changing things?

I am a believer of international instruments like ICPD’s Programme of Action, the Millennium Development Goals, and now the Sustainable Development Goals and the whole machinery that goes with them, to help countries understand what they call for and therefore take actions. International leaders and organizations can take advantage of such instruments to advance the lives of people everywhere. For MENA, these international frameworks help establish dialogue with nations and demand actions, without being labeled as “Western.” When then U.S. First Lady Hillary Clinton, at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, said famously that “human rights are women’s rights and women’s rights are human rights,” it didn’t apply to specific countries or cultures. What she said is timeless and applies to all women all over the world, including those in MENA.

Let me give a more concrete example as to how the international community sometimes can easily help change on the ground for girls and women in MENA and beyond. In the 2012 Olympic Games in London, for the first time in the history of the Olympics, every country had at least one female athlete on its national team, mainly because Saudi Arabia and Qatar did so for the first time. What prompted these two countries to send their women athletes to the games was that if they hadn’t, their male athletes could have not attended! Prior to the London games, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) had changed its regulations and made it mandatory for participating countries to have both male and female athletes in their national team—a simple move on the part of IOC, with everlasting impact on girls’ sport in the two countries and the region as a whole.

Q: You have also written recently about the situation in your native Iran. What is your prognosis for the country in terms of issues PRB follows?

Iran is a success story in the population field, but its isolation from the international community means relatively little has been known about it. At PRB, we published a policy brief on Iran’s successful family planning program in 2002 and its content is still fresh to many. I recently was contacted by the UNFPA office in Baku, Azerbaijan, asking me to visit and tell officials from the Ministry of Health, parliamentarians, and religious leaders about Iran’s family planning program. Azerbaijan has a low fertility rate—2.2 births per woman—and the majority of married women practice family planning, but they mostly rely on traditional methods. As a result, they have high rates of unintended pregnancy and abortion.

I remember once visiting the Minister of Health in Egypt in his office some years ago. While holding a copy of our policy brief on Iran in his hands, he said that “Yes, Tunisia also has a successful family planning program, but we want to know more about Iran.” He continued to say that the Iranian experience as an Islamic country was more relevant to Egypt than Tunisia’s, which was seen as having a “Western” style. But in my mind, the reality was that both countries were doing the same thing, making quality family planning services accessible to all married women through their primary health care system. The only difference that I could see between the two countries was that Tunisia was and still is more open to making family planning services available to unmarried couples.

Organizations like PRB should look for opportunities to disseminate information about how, in the 1990s, Iran went about implementing the ICPD’s recommendations to the extent that was possible for the country and explain its rural health network which was the key in reducing maternal and child deaths and closing the gap in modern contraceptive use between rural and urban areas. Countries in the region and beyond, such as Afghanistan and Iraq, and Central Asian countries and many African countries would benefit from such effort by learning from the Iranian experience.

Product: Presentation Slides

Author: PRB

Date: August 2, 2016

Some people find the demographic dividend a highly-technical topic that is difficult to communicate. PRB is a leader in communicating the links between population dynamics and development, and particularly on communicating demographic dividend research to nontechnical audiences.

PRB’s newest resource on the demographic dividend is a deck of sample PowerPoint slides that are intended for use by government and civil society stakeholders in their own presentations. This deck of sample PowerPoint slides provides a compelling overview of this complex topic through graphics, photos, text, and tables from PRB publications and multimedia products. Users can download these slides to tailor their own presentations. The slides include a basic definition of the demographic dividend, a description of the different components of a supportive policy environment, and some country-specific data from select countries.

Product: Policy Brief

Author: Farzaneh Roudi-Fahimi

Date: April 29, 2016

(April 2016) This PRB policy brief explores the lives of adolescent girls in Egypt. A national response that cuts across development sectors and programs is necessary because of the girls’ demographic significance and more importantly because they are vulnerable to harmful practices such as female genital cutting (FGC) and early marriage that violate girls’ rights and hinder the country’s development.

Girls under age 20—around 19 million of them—make up one-fifth of Egypt’s population. In 2015, about 8 million of these girls were adolescents between ages 10 and 19. According to the latest projections from the United Nations (UN) Population Division, this group will grow to 11.5 million in 2030—a 44 percent increase in 15 years.

While adolescent girls’ health and well-being have generally improved in Egypt, inequalities remain widespread. Girls’ school enrollment has risen significantly over the past few decades, but dropout rates remain high. The rate at which girls undergo FGC has been declining slowly and girls today are less likely to become child brides (married before age 18) than a generation ago—although the rate of child marriage has leveled off in recent years.

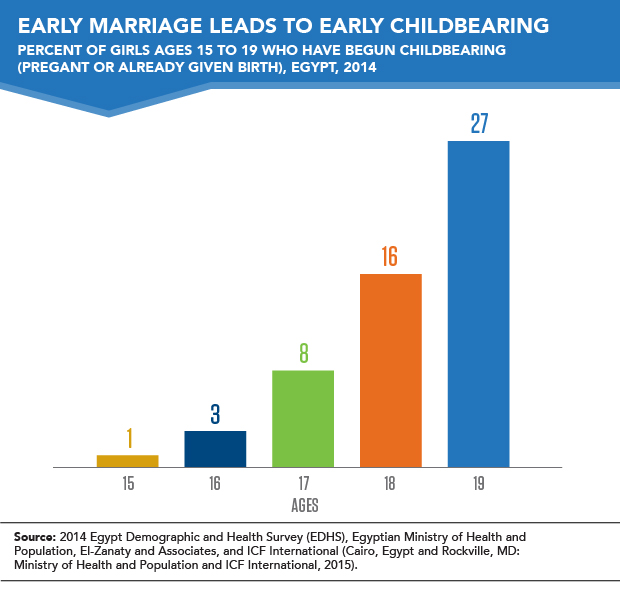

Early marriage for girls usually results in early childbearing, because newlyweds are generally expected to have a child soon after marriage, regardless of their age. The proportion of girls who begin childbearing—that is, they are either pregnant or have already given birth—rises rapidly throughout the teenage years as the proportion of girls who are married increases: The 2014 EDHS shows that 1 in 6 girls (16 percent) begin childbearing by the time they reach their 18th birthday. This ratio increases to 1 in 4 girls (27 percent) by the time they reach their 20th birthday (see Figure).

December 9, 2015

(December 2015) In late November, Nigerian parliamentarian Babatunde Gabriel Kolawole spoke in the National Assembly and implored his colleagues to come up with a viable policy to “curb the population explosion in Nigeria.” Already the seventh-largest country by population in the world, Nigeria is on track to be the fourth-largest in 2050, with nearly as big a population as the United States. Nigeria’s total fertility rate is a high 5.5 children per woman.1

According to news reports, Kolawole backed a proposed motion for population policy legislation with projections from PRB’s World Population Data Sheet as evidence of a brewing crisis and the need to take quick policy action to avert it.2

This was a timely example of the relevance of the Population Reference Bureau (PRB)’s work to provide practical, evidence-based knowledge of family planning and other critical policy issues that affect the well-being of current and future generations, both globally and in the United States. The event also highlighted the politically charged nature of family planning discussions in Nigeria. According to the reports, some members of the National Assembly saw Kolawole’s motion as a potential threat to the country’s Muslims, who reside mainly in northern Nigeria and make up roughly half of the country’s population.3 The reports cited Zakara Mohammed, another parliamentarian, as saying that in Islam and in northern Nigeria generally, having more than one wife and bearing as many children as one likes is acceptable practice.

In a subsequent interview with the National Mirror, Kowawole sought to clarify his position. He expressed his surprise that the motion was viewed as an attack on Muslims. “That was not the intention of the motion. The motion was simply asking that the federal government should take steps to manage the population, and…educate Nigerians on the benefit of family planning,” he said. He also emphasized that an “…unbridled and unmanageable population has negative consequences. Everyone knows that. If at an estimated 166 million we are still adding about 5 million births per annum, there should be cause to worry.”

The parliamentary exchange comes in the context of diverging population trends among Muslims and non-Muslims in Nigeria (see Table). In 1990, Muslim women of childbearing ages (15 to 49) had on average 6.5 births, compared to 5.6 for non-Muslim women (the latter are mostly Christians, but also a small percent of people practicing traditional religions). By 2013, non-Muslim fertility had fallen to 4.5 births, while Muslim fertility remained the same, leading to a two-child difference between Muslims and non-Muslims, according to a recent report by Princeton’s Charles Westoff and PRB’s Kristin Bietsch, published by the Demographic and Health Surveys.5 This difference in fertility will lead to faster population growth among Muslims than non-Muslims in Nigeria.

Table

Fertility Trends Among Muslim vs. Non-Muslim Women in Nigeria

| Muslim | Non-Muslim | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Fertility Rate (TFR) (1990)* | 6.5 | 5.6 |

| TFR (2013) | 6.5 | 4.5 |

| Age at First Marriage (years) | 16 | 21 |

| Never Attended School (%) | 65 | 9 |

| Use of Contraception (any method) (%) | 6 | 29 |

| Desire to Stop Childbearing (%) | 11 | 31 |

*Note: All data except for 1990 TFR are from 2013.

Source: Adapted from Charles F. Westoff and Kristin Bietsch, “Religion and Reproductive Behavior in Sub-Saharan Africa,” DHS Analytical Studies No. 48 (Rockville, MD: ICF International, 2015), accessed at www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/AS48/AS48.pdf, on Dec. 9, 2015.

Muslims girls and women tend to marry much younger than their Christian counterparts: The average age at first marriage is 16 for Muslim women, compared to 21 for non-Muslims.6 Also, 44 percent of married Muslim women are in polygynous unions, compared to 17 percent of non-Muslim wives.7 The differences in age at marriage also lead to differences in educational attainment for women: While only 9 percent of non-Muslim women in Nigeria have never attended school, the share is 65 percent for Muslim women.8

Only 6 percent of married Muslim women are currently using any form of contraception, compared to 29 percent of married, non-Muslim women.9 If family planning were widely available, fertility would not decline much among Muslims. On average, Muslim women in Nigeria wish to have more than eight children each, and also express less desire to halt childbearing: Three times as many non-Muslims wish to have no more children compared to Muslims (31 percent compared to 11 percent, respectively).10

Even when accounting for the socioeconomic differences between Muslims and non-Muslims in the country, the report finds that Nigerian Muslims are more likely to marry younger, to desire larger families, and to never have used contraception.

Note that this is not intended as a condemnation of reproductive preferences or practices of Muslims or any other group in Nigeria. Population growth rates should also not be forcibly changed and people’s rights should be respected. Rather, as Kolawale is cited as saying, the focus should be on public education about and availability of family planning options to help people decide when and how many children to have.

Product: Infographic

Author: PRB

Date: December 7, 2015

December 4, 2015

(December 2015) With the signing of the Iranian Nuclear Deal and subsequent easing of economic sanctions, new opportunities will arise for Iranian workers to compete in the global market. Due to high fertility rates in the recent past, Iran has a large working-age population that stands to perfectly capitalize on these developments, allowing the country reap its demographic dividend. Iran cannot afford to miss this window of opportunity.

Read the entire article in the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs.

China has abandoned its “one-child” policy, according to news reports. The policy was previously relaxed January 2014, but in response to the country’s aging population, the Chinese government has proposed an update allowing two children per couple.

China has the world’s largest population, and in the 1970s managed to achieve one of the fastest fertility declines in human history. The country’s one-child population policy has resulted in a number of unique demographic events and transitions. So what would be the demographic implications of this two-child policy?

Figure 1

Note: Projections calculated using Spectrum Software.

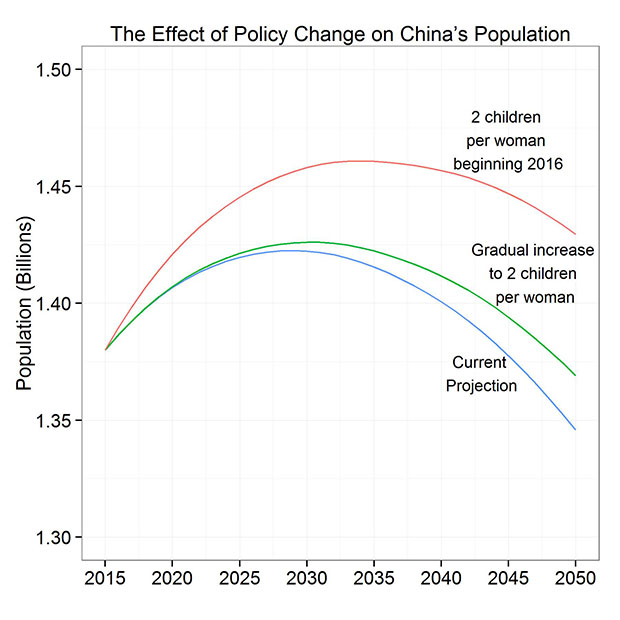

PRB demographer Kristin Bietsch calculated three scenarios of what population might look like in 2050 (see Figure 1). The current projection (blue line) is PRB’s projection under the old one-child policy for the population size of China. The population peaks around 2030 at 1.42 billion and begins to decline.

The high scenario (red line) is based on the idea that the total fertility rate (TFR) in China will increase to two children per woman in 2016 (a highly unlikely scenario given current desires for small families). This high scenario would peak only about five years later than the current scenario, at around 1.46 billion.

A more realistic projection is represented by the green line, where the TFR would gradually increase to around two children in 2050—a similar-looking trajectory to our current projection of China through 2030. If population increases gradually according to this scenario, it would also peak around 2030 at 1.43 billion people.

The bottom line: The difference in 2050 between the current projection and gradual increase scenario is 23 million people, less than 2 percent higher than PRB’s projection under the one-child policy.

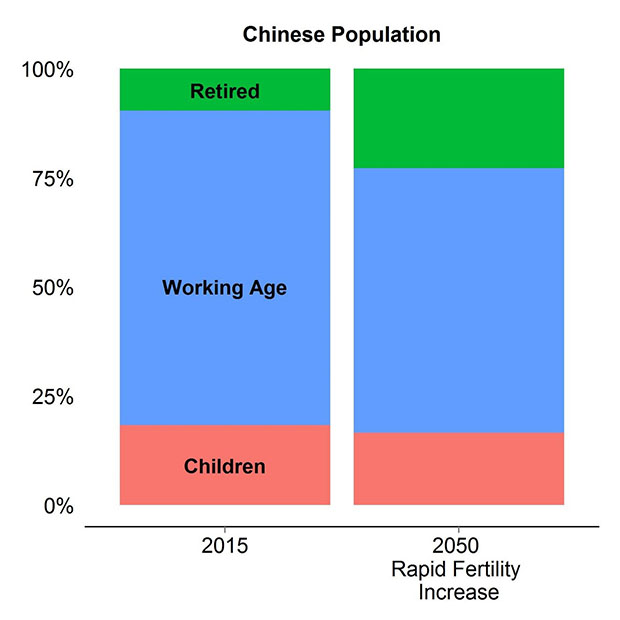

Figure 2 shows the age distribution in China for 2015 and 2050 if fertility increases immediately to two children per woman. Even with this increase, the age structure of China will change dramatically in the next 35 years, with a more than doubling of the retired-age (65 and older) population, and even a decrease in the number of children (those under age 15). There will be fewer working-age people per nonworking-age people in 2050 compared to 2015.

Figure 2

In 1989, on the first World Population Day designated by the United Nations, there were 5.2 billion people living on Earth. On July 11, 2015, we will be 7.336 billion, according to calculations by the Population Reference Bureau (PRB). This is up about 100 million from World Population Day 2014, meaning the equivalent of another Philippines or Ethiopia has been added to the planet.

What does the future bring? In mid-August, PRB will release its 2015 World Population Data Sheet with population projections for 2050. Below is a preview of numbers for the largest countries:

World population is now majority urban, but there are regional differences. For example, the populations of Africa and Asia—the biggest world regions—are still majority rural, with women in rural areas having more children than their urban counterparts. Use of modern contraceptive methods is generally higher in urban areas. Asia will soon become majority urban, but Africa, currently 60 percent rural, will not become majority urban for at least 20 more World Population Days.

Sound population policies and sound development are closely linked. The United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which expire this year, identified unmet need for family planning as an impediment to achieving Goal 5, improving maternal health. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which will succeed the MDGs and help frame the development agenda for the next 15 years, are likely to reinforce the critical role of family planning.

PRB is at the forefront of analyzing and communicating links between population and development. For example, PRB has partnered since 2006 with the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation to implement the Population and Poverty Research Initiative (PopPov) to help develop evidence on the economic impact of population dynamics. The latest PopPov research conference held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in June 2015, highlighted evidence on the relationships among women’s and children’s health, access to health care, and economic well-being (including education and employment), providing insight relevant to achieving the SDGs. This body of research has shown that investing in human capital through women’s health and education contributes to sustainable development.

Investing in human capital can also result in a demographic dividend, the boost in economic growth that can result from changes in a country’s population age structure as fertility rates decline. Over the last decade, for example, Ethiopia has experienced declining fertility rates and has made strong progress in improving the health and development of its people. If the country continues to make substantial investments in reproductive health and family planning, fertility levels may continue to decline, and surviving children will be more likely to achieve better basic levels of health.

A new website on the demographic dividend, co-hosted by PRB and the Bill & Melinda Gates Institute for Population and Reproductive Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, provides materials available from a number of organizations engaged in research, advocacy, and policy work on the topic. PRB’s new interactive feature showcasing successes under the USAID-funded IDEA project highlights work on the demographic dividend.

While the demographic dividend can provide a framework for national policy agendas to achieve economic growth, PRB’s Practical Guide to Population and Development addresses some key questions for decisionmakers to prioritize: How does population growth affect national development? What must be done to manage the challenges of population growth? The guide identifies some of the investments that are needed in family planning; education; and infant, child, and adolescent health to benefit from the demographic transition.

PRB also works at the country level to engage policymakers. For example, in Ghana, the issues of population growth and family planning are central to Ghana’s national development. On July 8, PRB and the National Population Council launched the multimedia advocacy tool, “Ghana on the Rise: Investing in Population and Development,” in Accra. The presentation, designed to promote policy dialogue on the critical role of population growth and family planning in achieving development goals, was viewed by high-level officials, including representatives of the vice president’s office, ministers of state and health, and the National Development Planning Commission.

“Ghana on the Rise” explores two scenarios: If Ghanaians continue to have families with an average of four children, the country will grow from 27 million to 60 million by 2050. But by addressing the reproductive health needs of families with a special focus on family planning, the population would reach a more sustainable 40 million.

In 2050, will world population growth rates be at manageable levels? Will governments be taking advantage of lower fertility rates to spur economic growth? PRB is working hard to ensure this is the case.

June 23, 2015

Over the next 15 years, public and private funders are likely to invest trillions of dollars to make progress towards the proposed Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These efforts must be strategic and targeted to improve the health, well-being, and standard of living for millions of people. Current and future research can inform decisionmakers about what types of investments have the potential to yield returns—and to what extent.

For the past decade, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and its funding partners in the United States, Europe, and Africa have supported research on the relationships between population dynamics, reproductive health, and economic development. In June 2015, the Population and Poverty (PopPov) Conference on Population, Reproductive Health, and Economic Development hosted researchers to present results that have been supported through these partnerships, as well as through other sources. The conference highlighted evidence that contributes to a better understanding of the relationships among women’s and children’s health, access to health care, and economic well-being, including education and employment, providing insight relevant to achieving the SDGs.

Findings show that investments in women’s health improve economic well-being for individuals and households. Access to appropriate health care, including family planning services, can help women and girls complete more years of education and participate in the labor force. Women with more years of education are more likely to delay marriage and childbearing and to gain the skills necessary for gainful employment than women with fewer years of education.1 Delaying childbearing was shown to improve educational and health outcomes for mothers and children (see Table).2

Table

Teen Mother Educational Attainment, Cape Town

| Teen Mother | Nonteen Mother | |

|---|---|---|

| Years of education completed by age 20 |

9.6 | 10.1 |

| Percent dropping out of school |

76.4 | 57.6 |

| Percent successfully completed high school by age 20 |

21.8 | 30.9 |

Notes: A teen mother is defined as a woman who has her first child by age 20. A nonteen

mother is defined as a woman who has her first child after age 20.

Source: Vimal Ranchhod et al., “Estimating the Effect of Adolescent Fertility on Educational

Attainment in Cape Town Using a Propensity Score Weighted Regression,” Southern Africa

Labour and Development Research Unit Working Paper 59 (2011). Mean differences are

statistically significant.

Researchers at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and Middlebury College in the United States are investigating the impact of the National Adolescent Friendly Clinic Initiative (NAFCI) in South Africa. NAFCI-accredited clinics provide health care and sex education services to adolescents without stigma from health care providers. The study found that girls who lived near a NAFCI clinic between ages 12 and 17 were substantially less likely to experience a birth before age 18 than their counterparts who lived further from a NAFCI clinic.3 Researchers estimate that clinic access also had a positive impact on years of schooling, which may influence employment and economic outcomes.

Similarly, a Cornell University study on the impact of early childbearing on educational attainment and cognitive skills among young women in Madagascar found that, after accounting for socioeconomic household and community characteristics, young women who lived in communities where condoms were accessible were less likely than those without access to have an early pregnancy. Women who experienced delays in childbearing were found to have greater educational attainment and better cognitive skills as indicated by math and French test scores than those who had children at an earlier age.4

Investments in health can also have intergenerational effects, leading to improved health and educational attainment of a woman’s children. Investing in nutrition is one example. Good nutrition before and during pregnancy affects the physical and mental well-being of both mother and child.5 These, in turn, influence the ability to learn and earn.

A collaboration between the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research in Bangladesh, the University of Colorado, and the University of Denver investigated outcomes of the Maternal and Child Health and Family Planning (MCH-FP) program implemented in Matlab, Bangladesh 19 years after its initiation. Findings showed that MCH-FP programs—which provided services such as family planning, vaccinations, and counseling on nutrition and hygiene—improved the cognitive function and educational attainment of children living in intervention areas in late childhood.6 Future research will examine whether these improvements in human capital continue into adulthood or fade. Results on migration, women’s economic empowerment, and employment are anticipated later this year.

An analysis of data from Burkina Faso found that children’s level of educational attainment is inversely associated with the number of biological siblings living in their household.7 Family units with fewer children may be more able to invest in those children’s human and social capital.

Social protection efforts can support school enrollment, educational attainment, and economic empowerment. Cash transfers and youth training, for example, are efforts that have been shown to promote economic empowerment and increase human capital.

A team of researchers from Norway and Tanzania conducted a field experiment in Tanzania to understand girls’ empowerment and fertility decisionmaking. When researchers compared entrepreneurship training alone, health training alone, or entrepreneurship and health training together, they found that entrepreneurship training alone and in combination with health training were more effective approaches for girls’ economic empowerment.8 Girls who completed the entrepreneurship training (alone or in combination with the health training) were more likely to be involved in business activities and be pleased with their economic situation a year later than those who only completed the health training.

Evidence on cash transfer programs demonstrate their potential to increase school attendance and influence sexual behavior and fertility decisionmaking, affecting both health and economic outcomes.9

Overall, studies across a variety of settings indicate that investing in women often spills over to their children and households, contributing to better health outcomes, increased human capital, and the economic growth of communities.10 Investing in human capital through women’s health and education contributes to sustainable development.

Learn more about the Population and Poverty Research Network.

Learn more about the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation’s Population and Poverty Research Initiative.