Paola Scommegna

Senior Writer

Part three of three articles excerpted from Today's Research on Aging, Issue 37: Health and Working Past Traditional Retirement Ages

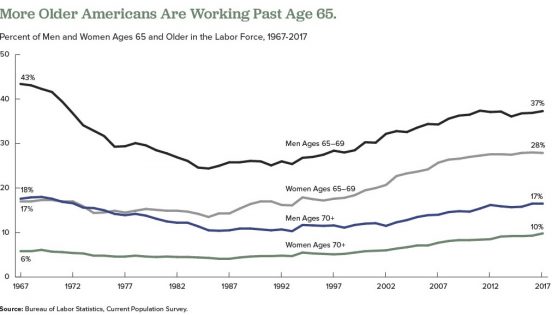

A growing share of Americans are working beyond their 65th birthday, a reversal that began in the mid-1980s. Labor force participation rates for men ages 65 to 69 began to drop in the mid-1960s, bottoming out at 24 percent in 1985, but have risen to about 37 percent in 2017. Among women ages 65 to 69, the labor force participation rate increased from 18 percent in 1964 to 28 percent in 2017.

Researchers have identified a variety of factors influencing older people’s decisions to postpone retirement over the past 25 years, including the following:

But researchers disagree on whether the upswing in the share of employed older people will continue as more members of the baby boom generation reach traditional retirement ages.

Some analysts argue that most of the factors listed above have played themselves out. Alice Munnell of Boston College points out that defined-benefit pensions and employer-provided retirement health insurance are almost entirely absent from the private sector; educational attainment has plateaued among the those now approaching retirement age; gains in health and longevity related to declines in smoking and improved medical care are being offset by increases in obesity; and blue-collar jobs have been rare for a generation.2

But other researchers argue that high levels of debt remain a powerful force that may contribute to more people postponing retirement. Annamaria Lusardi of George Washington University, Olivia Mitchell of University of Pennsylvania, and Noemi Oggero of the University of Turin find a “dramatic increase” in the amount of debt carried by older Americans nearing retirement ages, mainly the result of “having purchased more expensive homes with smaller down payments than previous generations.”3

They use data from the nationally representative Health and Retirement Study (HRS), an ongoing survey of older Americans, and the National Financial Capability Study (NFCS), a national sample of adults surveyed on financial planning and decisionmaking. Their analysis focuses on the debt of Americans ages 56 to 61 in 1992, 2004, and 2010.

They show that the median debt-to-income ratio (the percentage of income that goes to debt payments) climbed from 14 percent in 1992 to 45 percent in 2004, and to 50 percent in 2010. The median amount of debt rose sharply between 1992 and 2004, from $6,800 to $31,200 in 2015 dollars.

Their findings also indicate that older adults ages 62 to 66 in 2010 carried more debt than their counterparts from earlier years, though they carried less debt than adults ages 56 to 61 in 2010. “While people’s financial situation does seem to improve with age, the older group is still financially distressed,” they write. “Close to half (47 percent) of those ages 62 to 66 are worried about running out of money in retirement and just over half (55 percent) had planned for it [their retirement].”

In another study using HRS and NFCS data, Lusardi and Mitchell find that women in their 50s and 60s in recent generations are more likely to say they plan to work to older ages than their peers from the early 1990s.4 Respondents with plans to delay retirement tend to have higher levels of education, higher divorce rates, and fewer children, but “household finances also play a key role” in retirement decisions, they report. “Older women today have more debt than previously and are more financially fragile than in the past,” they write.

1 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Table 2. Employed Full- and Part-Time Workers by Disability Status and Age, 2016 Annual Averages,” last modified June 21, 2017, accessed at www.bls.gov/news.release/disabl.t02.htm, on Feb. 14, 2018.

2 Alicia Munnell, “The Average Retirement Age—An Update,” Center for Retirement Research, Boston College, No. 15-4 (March 2015).

3 Annamaria Lusardi, Olivia S. Mitchell, and Noemi Oggero, “Debt and Financial Vulnerability on the Verge of Retirement,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No.23664 (Aug. 2017).

4 Annamaria Lusardi and Olivia S. Mitchell, “Older Women’s Labor Market Attachment, Retirement Planning, and Household Debt,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 22606 (Sept. 2016).

April 23, 2018

Senior Writer

First in a series of three articles excerpted from “Health and Working Past Traditional Retirement Ages,” Today’s Research on Aging, Issue 37.

By 2030, when the last of the large baby boom generation (born 1946 to 1964) has reached their mid-60s, more than 21 percent of the U.S. population is projected to be age 65 or older—up from about 15 percent in 2016.

The greying of America increases the costs of public programs for older adults and shifts the balance between working people supporting those programs and retirees receiving benefits. The old-age support ratio—the number of working-age adults ages 18 to 64 for every adult age 65 or older—is on course to shrink dramatically from 4.1 in 2016 to 2.8 by 2030. To relieve this fiscal pressure, policymakers continue to discuss new financial incentives to encourage people to postpone retirement, such as further raising the eligibility age for Social Security (currently age 67 for those born after 1960) and Medicare (now age 65).

Working longer can reduce public spending and enable some older workers to enter retirement with more financial security. Estimates based on past health trends suggest that most U.S. older adults can work an extra two years before retiring.1But a growing body of research suggests that baby boomers in their 50s and 60s are in poorer health—with more chronic disease and disability—than earlier generations at the same ages, potentially affecting their capacity to work longer.

Older adults ages 51 to 61 had a higher prevalence of six out of eight chronic conditions—including 37 percent higher diabetes prevalence—in 2004-2010 than their peers in 1992-1998, a 2016 study finds.2 Hiram Beltrán-Sánchez of the University of California-Los Angeles, Marsha Jiménez of Brown University, and S.V. Subramanian of Harvard University analyzed self-reported chronic disease in the 1990s and 2000s using data from the nationally representative U.S. Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Based on their findings, they argue that older adults nearing traditional retirement ages appear more burdened by health conditions than several decades ago.

In another recent study, a University of Southern California research team finds Americans are living longer with more disability. Eileen Crimmins, Yuan Zhang, and Yasuhiko Saito examined life expectancy trends and disability rates in the 40-year period from 1970 to 2010.3They show that the average total lifespan increased for both men and women, but so did the proportion of time spent living with a disability. For people ages 65 and older, they identify a “compression of morbidity”—that is, a reduction in the proportion of life spent with disability. However, people in their prime working years (ages 20 to 64) experienced increases in the proportion of life spent with a disability. The researchers argue that there is “little evidence” of improvements in health “that would support increasing the age at retirement.”

In addition, a 2012 study that synthesized the results of five nationally representative surveys finds increasing disability among those ages 55 to 64 between 2000 and 2008 (a group that included the oldest baby boomers).4 During the same period, disability levels continued to decline among the oldest Americans (ages 85 and older) and held steady among those ages 65 to 84.

Linda Martin of the RAND Corporation, and Robert Schoeni of the University of Michigan also document rising disability levels between 1997 and 2010 among middle-age and older Americans (ages 40 to 64).5 Their analysis, based on the nationally representative National Health Interview Survey data, identifies a link between increasing obesity and rising disability.

Martin and Schoeni take this line of research further, teaming up with HwaJung Choi of the University of Michigan for a 2016 study focusing on 55-to-69-year-olds using HRS data for 1998 to 2010.6 They find no improvement in levels of physical functioning and activity limitations during the period, and some evidence of worsening. They show that obese individuals face a greater likelihood of having physical limitations. Although baby boomers are less likely to smoke, have emphysema, or have heart attacks, they are more likely to be obese or have diabetes or high blood pressure than the previous generation at similar ages, they report.

Obesity is a risk factor for a variety of chronic conditions; it may also increase the likelihood of early retirement due to disability. Using HRS data, Francesco Renna and Nidhi Thakur of the University of Akron find that men and women under age 65 who were obese in 1992 were more likely to have a disability and retire early by 2002.7

“Obesity can largely impact labor market decisions directly through impairment of bodily functions and indirectly by being a risk factor for various diseases like hypertension, arthritis, etc.,” they write. About two in five Americans (43 percent) in their 40s and 50s were obese in 2015-2016, and thus face an increased risk of retiring early because of a disability or poor health.8

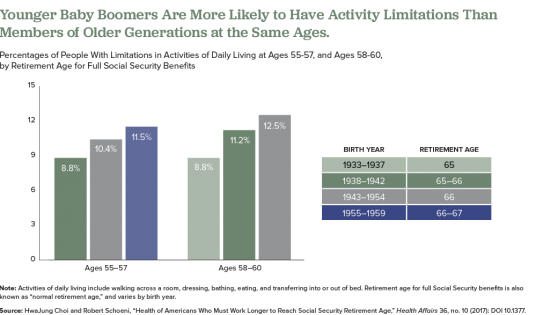

In a 2017 study, Choi and Schoeni examined trends in both physical limitations and cognitive impairment to compare the health of adults nearing retirement by generation.9 They find that adults in their late 50s today are in poorer health than their parents’ generation was at the same age, even though the younger group will have to work longer to collect full Social Security benefits.

For this study, they used HRS and National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data and divided older Americans into five groups based on the age at which they are eligible to collect full Social Security retirement benefits: those born in 1937 or earlier (age 65); those born 1938 to 1942 (between ages 65 and 66); those born 1943 to 1954 (age 66); those born 1955 to 1959 (between ages 66 and 67), and those born in 1960 to 1962 (age 67).

They find that the younger groups had higher shares of people who had at least one limitation on their ability to perform a basic daily living task by themselves, such walking across a room, dressing, bathing, eating, and transferring into or out of bed (see figure).

Also, they find that those born later tended to have higher rates of poor cognition, such as impaired memory and thinking ability, in their 50s compared with earlier generations at a similar age. Also, at age 50, people in the youngest group (born 1960 to 1962) were more likely to rate their own health as “fair” or “poor” than were people in the middle-three age groups when they were the same age, they report.

The researchers suggest that the increase of workers in their 50s and 60s who are in poor health will create significant challenges for them and their employers, including more people applying for Social Security disability payments. “Given the recent changes in health among the cohorts now approaching typical retirement age, further increases in the normal retirement age would place a substantial and disproportionate burden on these cohorts,” they argue.

The health of Americans in their 50s and early 60s today will shape labor force participation rates among the older population in the future. Understanding and monitoring these trends will be key as policymakers consider incentives to work longer and plan for future increases in the cost of public programs for older people.

Subscribe to our Today’s Research on Aging newsletter by sending an email to todaysresearch@prb.org with ‘Subscribe’ in the subject line.

1Courtney Coile, Kevin Milligan, and David Wise, “Health Capacity to Work at Older Ages: Evidence From the United States,” in Social Security Programs and Retirement Around the World: The Capacity to Work at Older Ages, National Bureau of Economic Research Conference Report, ed., David Wise (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

2Hiram Beltrán-Sánchez, Marsha Jiménez, and S.V. Subramanian, “Assessing Morbidity Compression in Two Cohorts From the Health and Retirement Study,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 70, no. 10 (2016): 1011-66.

3Eileen Crimmins, Yuan Zhang, and Yasuhiko Saito, “Trends Over Four Decades in Disability-Free Life Expectancy in the United States,” American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 7 (2016): 1287-93.

4Vicki Freedman et al., “Trends in Late-Life Activity Limitations in the United States: An Update From Five National Surveys,” Demography 49, no. 4 (2012).

5Linda G. Martin and Robert F. Schoeni, “Trends in Disability and Related Chronic Conditions Among the Forty-and-Over Population: 1997-2010,” Disability and Health Journal 7, no. 1 (2014): S4-14.

6HwaJung Choi, Robert Schoeni, and Linda G. Martin, “Are Functional and Activity Limitations Becoming More Prevalent among 55 to 69-Year-Olds in the United States?” PLoS One 11, no. 10 (2016): e0164565.

7Francesco Renna and Nidhi Thakur, “Direct and Indirect Effects of Obesity on U.S. Labor Market Outcomes of Older Working Age Adults,” Social Science & Medicine 71, no. 2 (2010): 405-13.

8National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), “Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2015-2016” NCHS Data Brief, no. 288 (Oct. 2017).

9HwaJung Choi and Robert Schoeni, “Health of Americans Who Must Work Longer to Reach Social Security Retirement Age,” Health Affairs 36, no. 10 (2017): DOI 10.1377.

With Americans living longer and the large baby boom generation reaching ages 65 and beyond, the sheer numbers of people with conditions of old age—including Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias—are expected to rise dramatically in coming years. But there is some potentially good news: The share of the population with dementia may have fallen over the past 25 years—likely the result of better brain health related to more schooling and aggressive treatment of high blood pressure and diabetes.

This report explores the evidence of a decline in dementia and the trends that may shape the future prevalence of this debilitating condition—focusing on recent work by researchers supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA).

It describes what we know (and do not know) about dementia patterns, examining known risk factors and vulnerable groups. This research can guide policymakers and public health professionals as they plan for an aging population and design strategies to address health and lifestyle factors related to dementia risk.

Neighborhood characteristics affect people of all ages, but older adults—classified here as adults over age 50—may be affected more than other groups.

Older people typically experience higher levels of exposure to neighborhood conditions, often having spent decades in their communities. They have more physical and mental health vulnerabilities compared with younger adults, and are more likely to rely on community resources as a source of social support. As older adults become less mobile, their effective neighborhoods may shrink over time to include only the immediate areas near their homes (Glass and Balfour 2003).

This report summarizes recent research conducted by National Institute on Aging-supported researchers and others who have studied the association between neighborhood characteristics and the health and well-being of older adults. This research can inform policy decisions about community resource allocation and development planning. A growing body of research shows that living in disadvantaged neighborhoods—characterized by high poverty—is associated with weak social ties, problems accessing health care and other services, reduced physical activity, health problems, mobility limitations, and high stress.

This area of research is challenging because lower-income people tend to live in disadvantaged neighborhoods and many detrimental neighborhood features cluster together. Disadvantaged neighborhoods often have more crime, more pollution, poorer infrastructure, and fewer health care resources—making it difficult to pinpoint which neighborhood feature is responsible for particular health outcomes.

Some researchers continue to focus on a single neighborhood feature and may incorrectly attribute health effects to the wrong characteristics. Others have created scales consisting of multiple features that are found together, which can mask the features that matter the most. In addition, most results are based on cross-sectional data (subjects interviewed at one point in time only) and may reflect people with more resources and in better health moving out of disadvantaged neighborhoods and those with fewer resources and worse health moving in or staying (Grafova et al. 2014). While existing research is not yet able to pinpoint exactly how neighborhoods cause changes in physical and cognitive health, researchers have identified a number of strong associations that point to possible pathways.

Neighborhood economic status—often measured by median household income or the share living below the poverty line—is one of the most widely studied and strongest predictors of the health and well-being of older adults. Older residents of economically disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to have chronic health and mobility issues and die at younger ages compared with older residents in more affluent communities. In part, these differences can be explained by the characteristics of people living in these neighborhoods, but a growing number of studies also suggest that neighborhood characteristics may independently influence older residents’ health and well-being.

Freedman, Grafova, and Rogowski (2011) use data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), which follows a nationally representative group of older adults, to look at the effects of neighborhood characteristics on six common chronic diseases: hypertension, heart problems, stroke, diabetes, cancer, and arthritis. They find that women living in disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to develop heart disease, even after controlling for individual characteristics and aspects of the physical environment (such as population density, pollution, and walkability). In another study using HRS data, Grafova and colleagues (2008) find that adults ages 55 and older living in more affluent neighborhoods are less likely to be obese, after accounting for individual differences and family characteristics.

Neighborhood conditions can also influence older adults’ self-perceived health status. Using data from the Study of Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old (AHEAD), Wight and colleagues (2008) find that adults ages 70 and older living in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely than their peers living in wealthier neighborhoods to report being in poor health. In fact, living in a disadvantaged neighborhood has a greater negative association with self-rated health status than either cardiovascular disease or functional limitations. Self-rated health is important because it reflects a person’s overall appraisal of their physical and/or mental health and tends to be closely related to a person’s actual health status.

Compared with cross-sectional studies that interview subjects at only one point in time, studies that capture neighborhood socioeconomic conditions earlier in life and track individuals over many years provide stronger evidence of whether living in a disadvantaged neighborhood is associated with poorer health later in life. Estimates based on the Panel Study of Income Dynamics show that living in low-income neighborhoods during young adulthood is strongly associated with poor health in later life (Johnson, Schoeni, and Rogowski 2012). The researchers find that one-quarter of the variation in mid-to-late-life health is linked to neighborhood disadvantage after accounting for individual and family differences. In another study, Glymour and colleagues (2010) measure neighborhood disadvantage with a six-indicator index, using HRS data that tracked respondents ages 55 to 65 over 18 years. Focusing on respondents who were disease free before the study began and statistically accounting for neighborhood change, they find that living in a disadvantaged neighborhood is associated with a greater likelihood of reporting poor self-rated health, but not disability or elevated depressive symptoms.

The level of income inequality in a local area may also influence health. Using HRS data, Choi and colleagues (2015) compare health outcomes of adults ages 50 and older with similar socioeconomic profiles in high-inequality and low-inequality U.S. counties. They find that older adults in counties with high levels of inequality report worse health status and more psychiatric problems than older people in low-inequality counties. Although the authors do not establish a causal link between income inequality and health status, they argue that high levels of inequality may contribute to “systematic underinvestment” in communities that could leave residents with “fewer resources to buy housing, healthy food, and medical care.” Income inequality may also be associated with lower levels of social cohesion and trust, leading to stress that affects residents’ mental and physical health, they suggest.

Extensive research has examined the link between neighborhood characteristics and mortality, but few studies have focused on this relationship among older adults. Using data from the Americans’ Changing Lives (ACL) survey, Yao and Robert (2008) find no significant association between living in a disadvantaged neighborhood and the mortality of adults ages 60 and older, after accounting for individual socioeconomic and health characteristics.

Wight and colleagues (2010) take this line of research a step further by examining the potential impact of multiple neighborhood characteristics on the risk of death among urban adults ages 70 and older, using data from the AHEAD study. Similar to Yao and Robert, they find no link between living in a disadvantaged neighborhood and risk of mortality after accounting for individual characteristics. People living in neighborhoods with a high proportion of Hispanic residents were at increased risk of mortality—a finding contrary to expectations that immigrant enclaves protect health by providing a source of social support for older adults. Ultimately, however, this risk was not significant after accounting for neighborhood affluence. Residents of affluent urban areas may be more aware of cutting-edge health care innovations and more likely to have the financial means to take advantage of them, the researchers suggest.

Neighborhood conditions can also affect the likelihood of older adults having functional limitations, such as difficulty walking. Freedman and colleagues (2008) look at the relationship between neighborhood conditions and disability among adults ages 55 years and older using HRS data. They find that older adults living in economically advantaged communities are less likely to develop problems with lower-body functioning compared with older adults in economically disadvantaged areas. Living in more affluent communities may help stave off functional problems during the early stages of disability, while living in disadvantaged communities may exacerbate functional limitations during the latter stages of decline. The authors argue that older people with greater wealth may be better able to prevent disease and disability, while those with limited income may be less able to fully recuperate or to adapt their homes to accommodate their functional decline.

Most researchers have focused on the effects of current neighborhood characteristics on health. But results based on this type of point-in-time approach may underestimate the effects of neighborhood characteristics on individuals over the life course. Clarke and colleagues (2014) use data from the ACL study to investigate the cumulative effects of neighborhood characteristics on functional decline among adults ages 25 and older over a 15-year period. They find that, over time, living in disadvantaged neighborhoods contributes to a 20 percent increase in the odds of developing a functional limitation and a 40 percent increase in the odds of dying, after controlling for racial/ethnic composition and individual socioeconomic factors. Although the study focuses on adults of all ages, older adults may face higher risks because they are more likely to live in disadvantaged neighborhoods and are much more likely than younger adults to die or experience functional limitations over time.

Long-term exposure to stress in disadvantaged neighborhoods may lead to “weathering,” a “cumulative biological impact of being chronically exposed to, and having to cope with, socially structured stressors,” explain Geronimus and colleagues (2015). The researchers argue that weathering can “increase health vulnerability and accelerate aging in marginalized populations.” For example, Geronimus and colleagues examine telomere length—an aspect of chromosomes that shortens with stress and aging—in a small sample of older residents from three Detroit neighborhoods. They link high levels of self-reported stress regarding personal safety to shorter telomeres and high levels of neighborhood satisfaction to longer telomeres.

King, Morenoff, and House (2011) find that neighborhood affluence is associated with fewer biological risk factors for chronic disease (such as high blood pressure and elevated cholesterol levels) after adjusting for individual-level social and economic background, using data from the Chicago Community Adult Health Study (CCAHS) on adults of all ages. Also using the CCAHS, King (2013) links neighborhood walkability to lower concentrations of C-reactive protein (CRP) in adults of all ages—a protein linked to inflammation, infection, and developing tissue damage and heart disease. But the same study links neighborhood density (a neighborhood feature sometimes related to walkability) to an increase in CRP, suggesting that aspects of densely populated neighborhoods—such as sleep-disturbing noise and pollution—may take a toll on health over time.

Clarke and colleagues (2012) show that living in an affluent community has a positive impact on the cognitive function of residents, after accounting for individual background, health, and risk factors. For the study, they use data from the Chicago Health and Aging Project (CHAP), which surveyed a racially diverse group of more than 6,000 adults ages 65 and older over 18 years in three adjacent Chicago neighborhoods. Using AHEAD data, Wight and colleagues (2006) show that adults ages 70 and older living in neighborhoods with low overall education have lower cognitive function than older adults living in areas with high education levels, independent of the elderly individuals’ own education and income level.

Aneshensel and colleagues (2011) find similar results when they link HRS responses with census data on neighborhood characteristics. Their findings show that living among more advantaged neighbors is associated with higher levels of cognitive function among people ages 55 to 65 with low education and income levels. Conversely, they find that older people with low socioeconomic status living in impoverished neighborhoods face the highest risk of poor cognitive function. They conclude that “being poor in a poor neighborhood” compounds the disadvantage. The researchers recommend neighborhood-level interventions that reduce disparities, such as “safe and accessible community centers where residents of poor neighborhoods can meet to discuss shared problems, obtain information about community activities, and interact with people with a wide range of life experiences.”

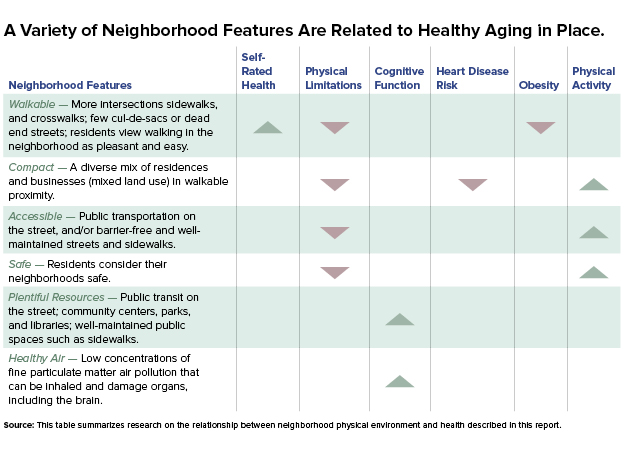

It is not only the economic characteristics of neighborhoods that affect health—but also aspects of the physical or “built” environment that promote walkability and foster interaction (see Table). Certain neighborhoods that are less accessible are particularly challenging for older adults with disabilities.

Tomey and colleagues (2013) find that neighborhood levels of sociability and walkability are positively linked to self-rated health among adults ages 45 to 84 in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Neighborhood walkability, as measured through street connectivity—a higher number of intersections and fewer dead-end streets or cul-de-sacs—has also been linked to a lower risk of self-reported disabilities and lower obesity rates (Freedman et al. 2008; Grafova et al. 2008).

The condition of neighborhood streets and sidewalks can make a big difference in the mobility of adults who have difficulty walking, according to Clarke and colleagues (2008). Adults with severe impairments are four times more likely to report a mobility disability if they live in neighborhoods with numerous cracks, potholes, or broken curbs in streets and sidewalks, according to their analysis of the cross-sectional CCAHS. The researchers suggest that if street quality could be improved, adults at greatest risk for disability could remain mobile and function independently for a longer period of time.

In a subsequent analysis using data from the ACL study, Clarke, Ailshire, and Lantz (2009) find that adults ages 75 and older living in compact neighborhoods with more accommodations for pedestrians are less likely, over a 15-year period, to report a mobility disability compared with those living in neighborhoods that are less pedestrian-friendly.

Among older adults with disabilities, well-designed neighborhoods can enhance outdoor activity. Older adults may be more likely to walk outside in pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods that they perceive as safe. For example, Satariano and colleagues (2010) find that older adults living in less compact residential areas—such as sprawling suburban neighborhoods—spend less time walking per week compared with those living in mixed-use or commercial areas. The authors argue that more compact communities may provide more walking destinations for older adults. However, compact neighborhoods are not associated with walking among those with poor functional capacity, who may perceive these areas as being less safe. “A compact area may have more walking destinations, but it also may have more streets to cross, cars to avoid, and greater pedestrian density,” the researchers note.

Similarly, Clarke and Gallagher (2013) find that older adults living in more accessible neighborhoods are more likely to walk outside in a typical week compared with those in less-accessible neighborhoods. Their study investigates the relationship between the built environment and mobility disability among adults ages 55 and older in Michigan. They create an innovative “accessibility score” using Google Earth’s “Street View” to measure pedestrian-friendly features such as smooth, barrier-free sidewalks and access to public transportation on the street.

Additionally, a study by Gallagher, Clarke, and Gretebeck (2014) shows that poor sidewalk design and perception of crime are associated with shorter walks. Women take longer walks if they have a destination, such as a friend’s house, while men are more likely to walk longer distances in higher-density, pedestrian-friendly communities.

The stress of living in disorderly neighborhoods (measured by the presence of trash, vandalism, safety problems, and broken curbs and sidewalks) appears to take a toll on the cognitive functioning of residents, according to Boardman and colleagues (2012). They focus on the gene APOE-E4 that has been linked to early-onset cognitive decline and is more common in people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Using CHAP data, they showed that older adults who carry the APOE-E4 gene have lower levels of cognitive function that decline more rapidly over time than those without the gene. But they demonstrate that the gene has the largest impact on the cognitive function of carriers who live in the most orderly neighborhoods, suggesting that when negative social conditions are eliminated, the genetic influence on cognitive function becomes more apparent.

Neighborhoods with more resources—parks, recreation centers, community centers, libraries—may buffer residents’ cognitive decline by creating greater opportunities for social interaction and physical activity. After taking into account individual background and health conditions, Clarke and colleagues (2015) use CHAP data to show that older people living in neighborhoods with community centers, accessible public transit, and well-maintained public spaces such as sidewalks tend to experience slower cognitive decline than similar adults whose neighborhoods lack these features. The researchers underscore the importance of keeping public spaces in good condition and maintaining barrier-free walkways, which may “support physical, social, and leisure activities for older adults.”

Recent studies demonstrate a link between exposure to higher concentrations of fine particulate matter air pollution and lower levels of cognitive function in older adults, even after taking economic and social differences into account. Inhaling small particles can damage organs, including the brain. Ailshire and Clarke (2015) examined a sample of non-Hispanic black and white men and women ages 55 and older from the 2001/2002 ACL study. They paired individuals’ tests of working memory and orientation with census tract level Environmental Protection Agency air monitoring data. Those living in areas with high concentrations of fine particulate matter pollution made 50 percent more errors than those exposed to lower air pollution levels. “Air pollution may represent an important modifiable risk factor for poor cognitive function in older adults,” the researchers assert. In a similar study using HRS data, Ailshire and Crimmins (2014) also find a link between fine particulate matter air pollution and cognition, particularly episodic memory. “Improving air quality in large metropolitan areas, where much of the aging U.S. population resides, may be an important mechanism for reducing age-related cognitive decline,” they suggest.

Neighborhood characteristics can also affect health by influencing the food residents eat. Kaiser and colleagues (2016) find that MESA participants who live in neighborhoods with healthier food environments—greater access to fruits and vegetables and to low fat foods—have a lower risk of developing high blood pressure. These findings suggest that “healthy food environments are associated with better diets and that better diets can reduce hypertension risk.”

While living in healthier food environments contributes to better health outcomes, living in unhealthy environments is associated with increased health risks. For example, Morgenstern and colleagues (2009) document that living in a neighborhood with a higher density of fast food restaurants is associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke among participants in the Brain Attack Surveillance in Corpus Christi (BASIC) project.

Older residents’ sense of neighborhood safety is key to their physical activity levels, particularly among those with disabilities. Using HRS data, Latham and Clarke (2013) find that older adults in neighborhoods perceived as safe are more likely to recover from a mobility limitation. The social environment also plays a role in recovery: Older adults who socialize with their neighbors are most likely to partially or fully recover from a severe mobility limitation (Latham, Clarke, and Pavela 2015). Those least likely to recover include women who have no neighborhood friends. The researchers suggest that “interventions aimed at encouraging older adults with mobility limitations to be engaged in their neighborhood” may contribute to improved physical functioning. However, older adults living in the same neighborhood as relatives are less likely to recover from a mobility limitation. Relatives may help people remain in their homes, but “overdependence on assistance from nearby family members could arise and have negative consequences for functional health and recovery,” they write.

Neighborhood safety is related to physical activity levels of older people of all socioeconomic backgrounds, report Tucker-Seeley and colleagues (2009) based on HRS data. Older people who perceive their neighborhoods as safe are more likely to engage in outdoor physical activity than those who consider their neighborhoods unsafe. The researchers suggest that programs designed to promote physical activity among older people should consider neighborhood safety concerns as potential barriers to participation.

Strong neighborhood social networks may blunt the “widow effect”the well-established finding that the death of a spouse increases the surviving partner’s risk of death. Subramanian, Elwert, and Christakis (2008) find that widowed men and women living in neighborhoods with high concentrations of older adults who have lost a spouse are less likely to die than those in neighborhoods with low concentrations. They suggest that in neighborhoods where widowhood is more common, widows and widowers may be more able to find similar individuals and renew or establish friendships that help replace the social support and companionship lost at a partner’s death.

Ethnic enclaves may protect the health of older adults in disadvantaged communities by supporting healthy behaviors and through stronger social networks. Data from the HRS show that residents of highly segregated Hispanic neighborhoods have higher levels of cognitive function (Kovalchik et al. 2015). But over time, individuals living in neighborhoods with high concentrations of Hispanics are more likely to experience rapid cognitive decline than people living in more integrated settings. The researchers suggest that strong social networks and multilingualism may create a “cognitive reserve” that raises the threshold at which cognitive deficits emerge. However, “once life stressors have accumulated and a clinical threshold for neurological damage has been passed, the decline in cognition is more precipitous,” they write.

While ethnic enclaves may be a source of social support for older adults, they can also signal high levels of racial/ethnic segregation, which can negatively affect health. A recent study links living in a neighborhood with high levels of segregation (concentrations of racial/ethnic minorities) combined with high crime to an elevated risk of cancer among older men and women (Freedman, Grafova, and Rogowski 2011). These neighborhood stressors may contribute to “a stress response that interrupts the body’s ability to fight cancer cell development,” according to the researchers.

Osypuk and colleagues (2009) study Hispanics living in neighborhoods with high concentrations of Latin American-born immigrants and find low levels of high-fat foods in their diets but also low levels of physical activity. Using HRS data, Grafova and colleagues (2008) also find that older men living in immigrant enclaves are more likely to be obese.

In another study using HRS data, Sudano and colleagues (2013) find that living in racially segregated neighborhoods (those with high shares of minorities) is linked to poor health largely because the older residents in these communities have less education, higher poverty rates, and lower levels of net worth compared with older adults in less segregated communities.

Kershaw and colleagues (2015) document that segregation affects cardiovascular risk differently for whites and for racial minorities. They find that living in highly segregated black neighborhoods is linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) among black MESA participants followed over 10 years. Conversely, living in more segregated white neighborhoods is linked to a lowered risk of CVD among white MESA participants.

Research on the ways neighborhood settings affect health, like all epidemiological research, allows researchers to describe risk factors and associations but not to estimate direct cause and effect. Nevertheless, the strong patterns identified by this research can help policymakers and planners design new health-promoting policies and better target intervention programs. In some cases, improving neighborhood safety or making changes to the neighborhood’s built environment improving sidewalks, for example may be more cost-effective ways to improve health outcomes among older adults than changing individuals’ health behaviors.

The potential negative effects of living in disadvantaged neighborhoods for the physical and mental health of older adults point to the need for neighborhood improvements that expand the quantity, quality, and accessibility of community resources (such as parks, libraries, and community centers) and enhance walkability and safety. For others in more affluent communities, policies should help older adults age in place so that they can live independently longer, avoiding or postponing the need for costly long-term care.

Some of the results suggest that different interventions may be needed for men versus women. For example, women are more likely to take long walks—an excellent way to maintain physical fitness—if they have a particular destination, while men are more likely to take walks in pedestrian-friendly communities. Older adults living with disability also have different needs than those without limitations, especially among those who may be isolated in less accessible or unsafe communities.

Future research should consider the longer-term impact of neighborhood characteristics over an individual’s lifespan. Although an individual’s neighborhood setting is recognized as having a cumulative effect, few studies take a longitudinal approach, often due to limitations in the available data. Given the persistent racial/ethnic disparities and high levels of racial/ethnic segregation in many U.S. neighborhoods, more research is needed to investigate the role of segregation on health outcomes among older adults and how to address it.

Jennifer Ailshire and Philippa Clarke, “Fine Particulate Matter Air Pollution and Cognitive Function Among U.S. Older Adults,” Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences 70, no. 2 (2015): 322-8.

Jennifer Ailshire and Eileen Crimmins, “Fine Particulate Matter Air Pollution and Cognitive Function Among Older U.S. Adults,” American Journal of Epidemiology 180, no. 4 (2014): 359-66.

Carol Aneshensel et al., “Are Neighborhood Socioeconomic Disadvantage and Racial/Ethnic Segregation Associated With Cognitive Functioning in Late Middle Age?” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 52, no. 2 (2011): 162.

Jason Boardman et al., “Social Disorder, APOE-E4 Genotype, and Change in Cognitive Function Among Older Adults Living in Chicago,” Social Science & Medicine 74, no. 10 (2012): 1584-90.

HwaJung Choi et al., “Are Older Adults Living in More Equal Counties Healthier Than Older Adults Living in More Unequal Counties? A Propensity Score Matching Approach,” Social Science & Medicine 141 (2015): 82-90.

Philippa Clarke, Jennifer Ailshire, and Paula Lantz, “Urban Built Environments and Trajectories of Mobility Disability: Findings From a National Sample of Community-Dwelling American Adults (1986-2001),” Social Science & Medicine 69, no. 6 (2009): 964-70.

Philippa Clarke and Nancy Ambrose Gallagher, “Optimizing Mobility in Later Life: The Role of the Urban Built Environment for Older Adults Aging in Place,” Journal of Urban Health 90, no. 6 (2013): 997-1009.

Philippa Clarke et al., “Cognitive Decline and the Neighborhood Environment,” Annals of Epidemiology 25, no. 11 (2015): 849-54.

Philippa Clarke et al., “Cognitive Function in the Community Setting: The Neighbourhood as a Source of ‘Cognitive Reserve’?” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 66, no. 8 (2012): 730-6.

Philippa Clarke et al., “Cumulative Exposure to Neighborhood Context: Consequences for Health Transitions Over the Adult Life Course,” Research on Aging 36, no. 1 (2014): 115-42.

Philippa Clarke et al., &ldqu

Research finds that a neighborhood’s physical features—from broken sidewalks and high crime to plentiful parks and low air pollution—may be related to older residents’ health and ability to age in place. This infographic provides an overview of recent research on features of the physical environment linked to age-related disease.

For more detail, see PRB’s Today’s Research on Aging 35 “How Neighborhoods Affect the Health and Well-Being of Older Americans.”‘

In the United States, the vast majority of care that allows older people to live in their own homes is provided by family members who do not receive pay for their services. As the older share of the population increases and people live longer with chronic disabling conditions, particularly dementia, meeting the care needs of older Americans will become more challenging for families.

This report highlights recent National Institute on Aging-supported research on the impact of caregiving on family members, the dynamics of caregiving within extended families, and the future need and availability of family care. As policies deemphasize nursing home care in favor of community-based long-term support services, a better understanding of the family’s central role in caregiving is needed. This perspective can help policymakers, health care providers, and planners identify and implement strategies that better meet the care needs of older Americans and improve the lives of the family members who care for them.

A variety of trends have contributed to a widening gap between older Americans’ need for care and the availability of family members to provide that care, raising the potential for growing unmet needs, a heavier burden on individual caregivers, and increased demand for paid care. The combined effects of delayed childbearing and longer life expectancy mean more adults in later-middle age may be “sandwiched” between the competing demands of their children and those of their aging parents and parents-in-law. Women—who have traditionally served as parent care providers—are more likely to be employed than in previous generations, limiting their availability, and increasing their time constraints.

Using the nationally representative Panel Survey of Income Dynamics (PSID), Wiemers and Bianchi (2015) showed a 20 percent increase between 1988 and 2007 in the share of women ages 45 to 64 who had both children and living parents or parents-in-law. One in 10 women in this age group provided significant parental care and either financial assistance or housing (within their homes for one year or more) to both an adult child (age 25 or older) and a parent during the period. Supporting multiple generations “may affect well-being in retirement if women decrease labor supply to care for parents or if money transfers to children are made at the expense of retirement savings,” the researchers argue.

Adults in their 50s, 60s, and 70s are more likely than those in previous generations to have divorced, increasing their likelihood of reaching old age without a spouse to assume the role of caregiver. Divorce also has implications for whether older adults will receive care from their children. In particular, divorce and remarriage may weaken adult children’s sense of obligation to provide elder care, particularly for fathers with whom they did not reside and for stepparents (Silverstein and Giarrusso 2010).

Taking a variety of trends into account including divorce, low fertility, and rising life expectancy, Ryan and colleagues (2012) created a model of the baby boom population to examine the future availability of family support. The model, based on census data and findings from the nationally representative Health and Retirement Study (HRS), allowed researchers to estimate how many baby boomers would have the types of family members who are the most common care providers—a living spouse or an adult child within 10 miles. The projections show that the share of 75-year-olds without the most common care providers will increase substantially between 2010 and 2030. Given the size of the baby boom population, the number of 75-year-olds without a spouse could more than double from roughly 875,000 in 2010 to 1.8 million in 2030, and those without an adult child nearby could increase by a multiple of six during that time—from about 100,000 to more than 600,000. The researchers suggest that baby boomers may need to rely on paid care providers or nontraditional caregivers such as siblings or stepchildren. Unmarried women with few economic resources are likely to be particularly disadvantaged by not having a spouse to provide care. To address this widening care gap, researchers argue for expanding long-term care insurance, designing aging-friendly neighborhoods, and planning for an increased demand for paid care services.

[inline-links post_ids=”3499″ /]

Another way to meet older adults’ care needs is to better involve grown children who live at a distance from their parents, proposes Piette and colleagues (2010). Their analysis of HRS data showed that one in three chronically ill older adults had no children nearby but did have adult children living elsewhere. And three in four grown children were in frequent contact with their aging parents despite distance, through phone calls or visits (especially those who lived within a one-hour drive). More than half of the older adults said they could rely on their children if they had a serious problem and that their relationships were amicable. Involving out-of-town adult children in parents’ medical care and medication management is one way to better meet the needs of this group of chronically ill older people, the authors suggest.

Satariano, Scharlach, and Lindeman (2014) identify a wide range of new technologies that can support older adults and their caregivers, such as electronic medication reminders and ingestible devices to improve medication compliance, and wearable sensors that immediately report abrupt movements related to fall or injury. They recommend that research on the safety and effectiveness of these devices include input from caregivers and give special attention to economic barriers to their use.

Providing uncompensated care for a spouse or parent living with physical limitations can be both rewarding and stressful, and new research has helped identify how— and under what circumstances—providing care to an older relative is beneficial or harmful to the care provider’s well-being.

Roth, Fredman, and Haley (2015) examined five studies that followed groups of people over time and found that those who became caregivers tended to live longer and had lower mortality rates than similar noncaregivers. The researchers noted that “most caregivers also report benefits from caregiving, and many report little or no caregiving-related strain.” In one of those studies, Brown and colleagues (2009) tracked more than 3,300 married people ages 50 and older for eight years using HRS data. They found that those who spent 14 or more hours weekly caring for a spouse had a lower risk of death than otherwise comparable non-caregivers.

But other evidence indicates that prolonged caregiving for a spouse can negatively affect physical and mental health. Two recent studies based on eight years of HRS data tracked older married people who did not have high blood pressure or cardiovascular disease (CVD) at the beginning of the study (Capistrant, Moon, and Glymour 2012; and Capistrant et al. 2012). Caregiving for 14 hours or more weekly for two or more years doubled the risk of CVD onset and significantly increased the risk of developing high blood pressure compared to other similar adults who were not caregivers. Becoming a caregiver for a spouse (14 hours per week or more) also significantly increased an older adult’s risk of depression, according to another study of married HRS participants (Capistrant, Berkman, and Glymour 2014). But long-term caregiving (for two or more years) did not elevate the risks further, suggesting that grief related to experiencing a spouse’s functional decline rather than the long-term “wear and tear” of caregiving may be at the root of depression.

New findings from the nationally representative 2011 National Study of Caregiving offer a window into how caregivers experience their roles and which caregivers might be at risk of debilitating stress. This study collected information on the entire network of caregivers of each adult age 65 or older with activity limitations identified as part of the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS), making it more comprehensive than previous large studies. Nine out of 10 informal caregivers are family members, mainly spouses or adult children (Spillman et al. 2014).

In interviews, nearly two out of three caregivers rated their caregiving experience as largely positive, pointing to benefits such as feeling closer to the care recipient and assured that the recipient was receiving high-quality care (Spillman et al. 2014). But one in 10 caregivers found caregiving a negative experience overall. Additionally, one in four caregivers surveyed said caregiving took an emotional toll and about one in seven cited either financial difficulties or physical problems related to their caregiving responsibilities. About one in six caregivers told researchers that they had more than they can handle, were exhausted at the end of the day, or had little personal time.

Those who experienced caregiving as negative and stressful tended to care for recipients with greater limitations or with dementia symptoms, provided more hours of care, or had health problems of their own. Specifically, caregivers with symptoms of depression and anxiety as well as those with their own physical limitations were much more likely to experience caregiving as negative and stressful.

Researchers are gaining a better understanding of how the stress and time demands of intensive caregiving may weaken the immune system and increase the risk of accelerated aging by examining telomeres—structures found on the ends of chromosomes that protect against DNA damage. Over the past decade, a growing body of research has identified links between shorter telomeres and increased risks for depression and for a number of chronic diseases, including CVD, some cancers, and diabetes. Researchers have documented that caregivers experiencing the greatest stress have shorter telomeres than other caregivers, adding to evidence that chronic stress affects caregivers’ bodies at the genetic and molecular level (Litzelman et al. 2014). Another study that examined differences in telomeres suggests that the chronic stress spouses and adult children experience while caring for Alzheimer’s disease patients may shorten the caregivers’ lives by as much as four to eight years (Damjanovic et al. 2007).

For an older married person living with a disability, the spouse is usually at the forefront of care activities. And traditionally, parents have tended to rely on daughters (and daughters-in-law) for more care than sons. Recent studies examining the dynamics of elder care within families show how gender and proximity continue to influence who makes up an older person’s network of caregivers.

Wives tended to be the sole care providers for their husbands no matter how much personal care the men needed, according to analysis of the HRS-related Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old (AHEAD) study, which examined more than 7,000 adults ages 70 and older not living in nursing homes in the early 1990s (Feld et al. 2010). But the more functional limitations a wife had, the less likely her husband was her only caregiver and the more likely others helped provide her care, particularly daughters.

This difference in who provides care for married men and women may reflect the fact that many wives are younger than their husbands and are often less disabled. Hands-on caregiving is frequently central to a woman’s identity and may cause her to resist seeking or accepting help, suggest Feld and colleagues (2010). Another study, based on HRS data, showed that adult children tend to be involved in their mothers’ care no matter what their fathers’ health level, but are much more likely to provide care for their fathers after their mothers’ death (Noël-Miller 2010).

If a couple has both sons and daughters, the daughters are much more likely to become their mother’s primary caregivers, underscoring the “primacy of the mother-daughter tie,” report Leopold, Raab, and Engelhart (2014). Their analysis of HRS data tracked 2,400 previously independent adults and their grown children over a decade. Geography was the main factor determining which adult child provided care when a parent began needing assistance; caregivers’ work and family constraints had somewhat less influence. Other factors influencing caregiver selection included parent expectations, frequency of contact before the caregiving need arose, and whether the parent had provided financial assistance to the adult child or made the child a beneficiary of a will.

Among siblings, daughters and grown children living in close proximity to parents were more likely to be continuous care providers, according to another HRS-based study that tracked changes in primary caregivers over a two-year period (Szinovacz and Davey 2013). Parents were more likely to experience a switch in caregivers if they lived alone, had more sons than daughters, or had a higher number of children (and thus more alternative caregivers). The researchers found that the choice of a primary caregiver had more to do with expected gender norms and availability than adult children’s competing obligations such as work or family. The researchers point out that society has traditionally expected daughters to care for their parents and argue that it might be “psychologically more costly for women to decrease their care commitments,” despite the burden or conflicts they may experience.

The dollar value of the informal care that family and friends provide for older Americans totals an estimated $522 billion a year—more than total Medicaid spending ($449 billion in 2014), according to Chari and colleagues (2015). The researchers used new data from the 2011 and 2012 American Time Use Survey—which uses a relatively broad definition of elder care—to calculate the monetary value of the time uncompensated caregivers gave up in order to provide care. Replacing that care with unskilled paid care at minimum wage would cost $221 billion, while replacing it with skilled nursing care would cost $642 billion annually. Because most caregivers are employed, “the bulk of the economic burden of elderly care is shouldered by working adults,” the researchers argue.

Caregiving responsibilities appear to influence labor force participation, according to a study based on HRS data (Van Houtven, Coe, and Skira 2013). Providing personal care assistance to a parent slightly reduced men’s likelihood of working and may lead employed women to work fewer hours. The researchers suggest that women may seek lowerpaying jobs with more flexibility to accommodate caregiving. Among older workers who left a full-time position, taking on new caregiving responsibilities appeared to act as a barrier to working part time, according to Carr and Kail’s analysis of HRS data (2012). The more caregiving responsibilities the individuals had, the less likely they were to work parttime. “Providing support to new caregivers as they leave fulltime work may help them remain engaged in the workforce longer,” the authors suggest.

To estimate the impact of parent care on adult daughters’ current and future labor force participation and earnings, Skira (2015) created a model that accounts for declining parental health, the impact of a leave on daughters’ work history and experience, and the availability of job offers afterward. Incorporating data from HRS, she found that after taking an employment leave or cutting hours to provide parental care, the chances are low that adult daughters will return to work or increase their work hours. “Women who leave work forgo experience and the associated wage returns and also face a lower expected wage if they return to work,” she writes. The model suggests that the overall median cost to a woman in her mid-50s who leaves work is about $165,000 over two years, about equal to the cost of two years of nursing home care. This estimate is many times higher than estimates that only take into account the cost of lost wages.

Family caregivers provide the majority of support that allows older adults with disabilities to live independently and avoid costly nursing home care. The estimated dollar value of uncompensated family care overshadows many large federal programs.

As the disproportionately large baby boom generation ages, the gap between elder care needs and available caregivers will widen dramatically. In 2010, there were seven potential caregivers ages 45 to 64 (the age group of the average family caregiver) for every person age 80 and older (the age group most likely to have a disability) (Redfoot, Feinberg, and Houser 2013). That ratio is projected to drop to 4 to 1 by 2030 and bottom out at 3 to 1 in 2050 when the entire baby boom generation passes the age 80 milestone. The shrinking pool of potential caregivers reflects the combined impact of lower fertility and longer life expectancy; the former reduces the number of adult children and grandchildren that an older person can turn to for care and the latter increases the length of time individuals may need care. This demographic shift is occurring alongside other trends that also limit the availability of potential caregivers, including an increased share of employed women and caregiving expectations weakened by divorce.

To meet the growing care needs of older people, researchers underscore the importance of anticipating a growing demand for paid care services and designing neighborhoods that allow older people with disabilities to age in place more easily. Policies that enable employed caregivers to manage their competing roles are key to keeping families from seeking nursing home care for the older adults with functional limitations. Researchers also point to innovative approaches, such as designing ways to involve adult children living at a distance in managing their elderly parents’ health care.

New surveys document high levels of unmet care needs, particularly among older people with low incomes. New data on caregivers identify those who face particularly high caregiving burdens, such as those caring for older people with dementia or more mild cognitive impairment. These new data can guide policymakers and planners as they target home-based support services and caregiver assistance programs. Indeed, policies that improve long-term care services and supports, and reduce unmet needs, could benefit both older adults and their caregivers, now and in the future.

Please refer to PDF for references.

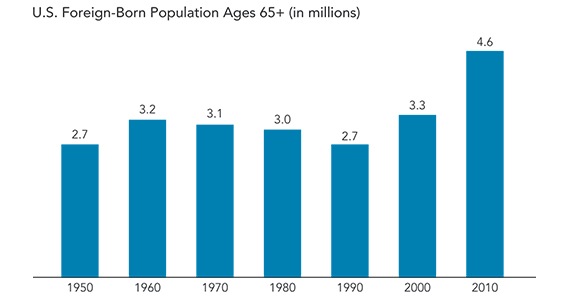

In 2010, more than one in eight U.S. adults ages 65 and older were foreign-born, a share that is expected to continue to grow. The U.S. elderly immigrant population rose from 2.7 million in 1990 to 4.6 million in 2010, a 70 percent increase in 20 years (see figure). This issue of Today’s Research on Aging reviews recent research examining older immigrants in the United States, conducted by National Institute on Aging (NIA)-supported researchers and others. Understanding both the unique characteristics of elderly foreign-born adults and the challenges some of them face is important as policymakers and planners address the well-being and health of the United States’ aging population.

The U.S. Foreign-Born Population Ages 65+ Increased Substantially Between 1990 and 2010.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, historical census data 1950-2000; and Current Population Survey, 2010.

Fueling the growth of the U.S. immigrant population ages 65 and older are two trends—the aging of the long-term foreign-born population and the recent migration of older adults as part of family reunification and refugee admissions. Analysis of American Community Survey data suggests that 10 percent of immigrants ages 65 and older had been in the country fewer than 10 years in 2010. Most U.S. immigrants who settle in this country after age 60 are sponsored by their adult children who had immigrated to the United States as young adults.

Long-term immigrants who arrived in the United States as children or young adults tend to face challenges similar to their U.S.-born peers. By contrast, immigrants who migrate after age 60 are often a “potentially vulnerable population” due to limited English language proficiency, little or no U.S. work experience, and weak ties to social institutions, reports Judith Wilmoth of Syracuse University. They face rules barring them from participating in most entitlement and welfare programs unless they become naturalized citizens, but their language skills and age are often barriers to naturalization. Compared to immigrants who arrive earlier in life, late-life immigrants are more likely to be female, to have low education levels, to have limitations in physical functioning, and to be widowed.

Foreign-born elderly tend to have less personal income than U.S.-born elderly, on average. Reliance on a different mix of economic resources in old age accounts for some of the income differences between immigrant and U.S.-born elderly, according to George Borjas of Harvard University. In 2007, U.S.-born elderly ages 65 and older were considerably more likely than immigrant elderly to receive Social Security benefits, investment income, and retirement benefits such as pensions. Immigrant elderly were more likely to be employed than U.S.-born elderly, driven in part by incentives related to Social Security program eligibility.

Immigrant elderly are more likely to have incomes below the poverty line than U.S.-born elderly. In 2010, 8 percent of U.S.-born elderly lived below the poverty threshold, compared to 16 percent of foreign-born elderly. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that within the foreign-born population ages 65 and older, 15 percent of Asian immigrants, 21 percent of all Hispanic immigrants, and 23 percent of Mexican immigrants lived below the poverty line in 2010.

The publication also explores recent research on the living arrangements, life expectancy, health, and disability levels of older immigrants in the United States.

Despite having lower income and education levels, U.S. Hispanics tend to outlive non-Hispanic whites by several years (see table).

Demographers call this the “Hispanic Epidemiological Paradox.” And for nearly three decades, they have puzzled over why Hispanics’ socioeconomic disadvantages are not linked to shorter lives, as they are for other racial and ethnic groups.

“Infant and adult mortality rates are strongly associated with income and education levels,” said Mark Hayward, a University of Texas, Austin, demographer. “People who have low incomes and lack high school degrees have very high mortality rates compared to people with high incomes and education.”

While Hispanics’ poverty and education levels are closer to those of U.S. blacks, their mortality rates are more similar to non-Hispanic whites, he noted. The question is: “How do U.S. Hispanics defy the odds?”

One explanation is that cultural factors—such as better health habits and stronger networks of social support in the Hispanic community—may offer protection from some diseases and lead to longer lives.

| Birth | Age 65 (years remaining |

Age 75 (years remaining) |

|

| Both Sexes | |||

| Total Population | 78.7 | 19.1 | 12.1 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 78.8 | 19.1 | 12.0 |

| Black | 75.1 | 17.8 | 11.6 |

| Hispanic | 81.2 | 20.6 | 13.2 |

* Black totals include Hispanics.

Source: National Center for Health Statistics, “Deaths: Final Data for 2010,” National Vital Statistics Report 61, no. 4 (2013): Table 7.

Older U.S. Hispanics tend to be healthier than non-Hispanic whites or blacks, Hayward and his colleagues have found.1 Fatal chronic diseases—heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, and stroke—are much less prevalent among older Hispanics than among other racial and ethnic groups. Their analysis was based on the Health and Retirement Study, a nationally representative sample of Americans and other U.S. residents age 53 and older.

Foreign-born Hispanics who immigrated to the United States “appear to be particularly healthy,” having rates of several major chronic diseases equal to or lower than whites, Hayward reported. “Their health advantage is even more pronounced when we controlled for income and education.”

But what is at the root of this better health, particularly among the foreign born? Lower tobacco use among Hispanics is an important explanation, argue demographers Laura Blue, of Princeton University, and Andrew Fenelon, of the University of Pennsylvania. Their analysis suggests that smoking could explain close to three-quarters of the difference in life expectancy at age 50 between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites.2 Only a small share of Hispanics smoke at all, and those who do tend to smoke fewer cigarettes than do non-Hispanics white smokers. This contributes to fewer smoking-related deaths (particularly from lung cancers and respiratory diseases) among Hispanics than among other groups.

Hayward and his colleagues offer more evidence on the power of smoking to shorten lives and explain Hispanics’ longer lives.3 They probed mortality differences among Americans ages 50 and older, paying attention to race, ethnicity, and country of birth. When they eliminated all smokers from their analysis, foreign-born Hispanics’ life expectancy did not significantly exceed that for non-Hispanic whites. In addition, U.S.-born Hispanics’ life expectancy dropped below that for non-Hispanic whites.

“Given that many older non-Hispanic whites in the birth cohorts represented in current studies have a legacy of smoking that most foreign-born Hispanics don’t share, it isn’t surprising that smoking plays such an important role,” he said.

Among nonsmokers, they found that mortality rates for U.S.-born Hispanics fell between whites and blacks. But, even among the smokers, foreign-born Hispanics “still had surprising good mortality rates.”

Are Hispanics’ relatively healthier than other groups just because very few “light up” or are there additional dynamics involved, Hayward wonders. Their health habits are not uniformly better than non-Hispanic whites: Older foreign-born Hispanics (ages 50 and older) are less likely to smoke and drink than whites, they are just as likely to be obese and they exercise about the same amount (which is, on average, not very much), he noted.

“Perhaps foreign-born Hispanics were thinner when they were younger, so they have had less lifelong exposure to obesity,” he said. “We have no way of knowing this given the way data are collected.”

And not everything about life in a Hispanic neighborhood is healthy. As part of a larger study on atherosclerosis, researchers tracked Hispanics living in neighborhoods with high concentrations of Latin American-born immigrants. They found that older Hispanics tended to consume low levels of high-fat foods but also did not get much physical activity.4 Living in an immigrant enclave is not uniformly conducive to good health, they concluded.

Researchers don’t know what mix of habits buffer Hispanics from chronic diseases. It could be a combination of social support through family and church, physically demanding work early in life, traditional diets, and limited smoking, Hayward suggested.

Migration patterns play an especially important role in older U.S. Hispanics’ puzzling advantages. Immigrants who leave the United States to return to their birthplace may do so when their health deteriorates (called return-migration effect or “salmon bias,” referring to the way salmon swim upstream near the end of life).

Demographers Alberto Palloni, of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Elizabeth Arias, of the National Center for Health Statistics, explored a number of different sets of data and found evidence that older Mexican-born Hispanics return to Mexico when ill, potentially inflating U.S. life expectancy rates.5 Examining Social Security data, Cassio Turra, of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brazil, and Irma Elo, of the University of Pennsylvania, found that foreign-born Hispanics who left the United States had higher mortality levels than those who remained, particularly among the most recent returnees.6 While the share of Hispanics who returned to their countries of origin was too small to fully explain Hispanics’ longer life expectancy, it is a piece to the puzzle.

Hispanics who migrate to the United States also tend to be healthier than their peers who do not leave their home country (known as a selection effect). Recently, demographers Fernando Riosmena, of the University of Colorado at Boulder, Rebeca Wong, of the University of Texas Medical Branch, and Palloni found “modest” evidence of both selection and return migration when they compared four groups of men ages 50 and older—Mexican-born men with experience living in the United States, Mexican-born men who never lived in the United States, U.S.-born men of Mexican descent, and U.S. non-Hispanic whites.7 Using nationally representative data from both the U.S. National Health Interview Survey and the Mexican Health and Aging Study, they examined self-reported health, hypertension, obesity, and diabetes.

Returnees were more than three times more likely to rate their health as fair or poor, compared to their Mexican-born peers who remained in the United States, offering evidence of a return-migration effect. Also, nonmigrants were about 1.5 inches shorter than migrants, suggesting a selection effect. Surveying their results across multiple measures, the authors concluded that emigration selection plays a stronger role than return migration.

While foreign-born U.S. Hispanics live longer than other U.S. groups, they appear to spend more of those years disabled, according to Hayward. One preliminary study suggests that disability levels rise steeply among foreign-born Hispanic men after age 50, making them more likely to be disabled than non-Hispanic white men between ages 50 and 75.8

The physical jobs they spent their lives working could explain the pattern, he speculated. While foreign-born Hispanic men may have been healthier than average at the start, manual labor likely took a physical toll and caught up with them later in life.

Disability also is a function of job options and education, he noted. With the right education and skills, someone with back problems can continue working at a desk job but harvesting crops becomes difficult, for example.

Hayward expects the Hispanic advantage in life expectancy to diminish somewhat over time because “there’s strong evidence that the second generation Hispanics [the U.S.-born children of foreign-born immigrants] become acculturated and adopt behaviors such as smoking.” Their health is more consistent with their education and poverty levels, more similar to non-Hispanic whites and African Americans, he said.

“We see a big divide by nativity among Hispanics; the Hispanic paradox is mostly a story about the foreign born,” he said.

But Hispanics’ life expectancy advantage is unlikely to completely disappear. “Smoking is still very low among younger foreign-born Hispanics, especially young women,” he pointed out.

In the next two decades, the number of Americans age 55 or

older will swell from 76 million to 110 million as the large

baby-boom generation continues to age. Older Americans’

health and well-being is important for the entire society, and

the longer they can live independently, the lower the social

costs will be for the society as a whole. This e-newsletter provides

an overview of demographic characteristics of older

volunteers and highlights recent findings from research affiliates

of NIA-supported centers specializing in the demography,

economics, and epidemiology of aging.

Whether older Americans can delay or prevent disability

associated with advanced age will depend in part on how

they spend their time after retirement. A growing body of

research suggests that older adults who are engaged in social

and community activities maintain mental and physical

health longer than other older adults (Musick and Wilson

2008). Volunteer activities are one way of remaining socially

active after retirement (Luoh and Herzog 2002).

Beyond potential health benefits for the volunteers, nonprofit

organizations, governments, and community groups

see boosting volunteering among the increasing older population

as furthering several complementary goals, including:

Many local and national government officials believe that

increased volunteerism among older people would be a “win-win”

situation, with multiple beneficiaries. In the United

States, a 2005 White House Council on Aging called for

enhanced volunteer opportunities for older Americans

(Butrica, Johnson, and Zedlewski 2009), and in 2009,

President Barack Obama signed the Edward M. Kennedy

Serve America Act, which aims to increase volunteer service

opportunities for older adults (Barron et al. 2009). Other

developed countries, many aging much faster than the United

States, are also attempting to harness the benefits of volunteering

for their societies and for their older populations (Musick

and Wilson 2008; Australian Bureau of Statistics 2010;

Statistics Canada 2010; Hank and Erlinghagen 2010).

Volunteering is generally defined as unpaid work for or

through an organization. It is distinct from informal “helping”

or caregiving, in which people may assist neighbors or friends

with certain tasks, such as grocery shopping, child care, or

yard work. While there is often overlap, these activities appear

to have different effects and involve different types of people

(Hank and Stuck 2008). People who commit to formal volunteering

are more likely also to engage in “helping,” but not the

reverse—people who help are not more likely to volunteer.

For example, someone who volunteers for their church may

also give informal help to a church member who cannot drive,

but someone who helps their disabled neighbor will not necessarily