Mark Mather

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

Exploring New Ways to Use Data for Good

Since Population Reference Bureau’s (PRB’s) founding in 1929, the world has changed tremendously and PRB has evolved along with it. We continue to explore new ways of working (globally, locally, even remotely) and hone our expertise to offer solutions relevant to today’s health and well-being challenges, such as the growing prevalence of noncommunicable diseases and the increase in anxiety among young people. What hasn’t changed is PRB’s impact on informing evidence-based practices, which you’ll see highlighted in this report.

In Fiscal Year 2023, we reached wide audiences with analyses and assessments on issues such as population aging, climate adaptation, maternal health, unpaid care work, and big data. We partnered with organizations like the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, Regional Consortium for Research on Generational Economy, Southern California Association of Governments, and William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. And the people who work here have made it all possible.

Part of any organization’s evolution is change in those people. From PRB’s original staff of 8 to 55 today, we’ve seen a lot of great people walk through our doors. In late 2022, we welcomed a new Vice President to lead our U.S. Programs, Diana Elliott. Midway through 2023, we appointed our first Africa Director, Aïssata Fall. And just a few months ago, PRB’s Board of Trustees appointed me as President and CEO. PRB’s new leadership is guided by the organization’s strategic plan to explore new areas of focus and ways of working while keeping population and demographic data at the core of what we do. It is a strong foundation from which to move forward toward our 100th year in 2029.

Our partners outside the organization are also essential to PRB’s success. My predecessor, Jeffrey Jordan, collaborated with other international organizations in 2023 on the TIME Initiative, an ongoing effort to answer hard questions about the evolving role of international nongovernmental organizations working in sexual and reproductive health and rights. I am pleased to be stepping into this space as I take the helm at PRB.

Barbara Seligman, Senior Vice President of International Programs, led the way in making PRB’s presence more prominent in 2023 as she advocated for our return to hosting more public events like the webinar on young Africa’s potential to power the global workforce. Diana Elliott quickly became another energetic force behind PRB’s increased public engagement, from authoring blogs that delve into the heart of current population concerns to speaking with the media and other organizations. And Reena Atuma, our Team Lead in Kenya, works daily alongside staff and local officials, youth, and others on concrete policy changes aimed at improving people’s health.

There’s so much more. We’ve captured some of the highlights for you in this year’s annual report.

Sincerely,

President and CEO

![]()

Under the PROPEL Health project, we worked with partner radio stations and community youth in nine districts across Malawi to raise awareness of social challenges around topics concerning nutrition, education, and health services; and harmful cultural norms like child marriage. We supported these local actors in their efforts to make context-specific, change-oriented information on these topics available in their communities and get people talking about them.

And they’ve made an impact.

Local radio programs in Malawi are now using their platform to hold leaders accountable for enforcing the child marriage law, and they are educating communities on how to respond to and prevent gender-based violence.

After a series of radio programs on child, early, and forced marriage and gender-based violence aired, a traditional authority in Monkey Bay in Malawi’s Southern Region publicly committed to enforcing the law against child and forced marriage, stating, “Dzimwe Radio has been insisting that I intervene and show my commitment in dealing with child marriages—hence my order to demote those village heads [found to not be enforcing the law].” In Mchinji, in Malawi’s Central Region, local police began holding town meetings about gender-based violence, and community members involved police and victim support units in investigations that led to the dissolution of child marriages, and arrests and fines for adult perpetrators.

And after Mudzi Wathu Radio aired programs about youth mental health challenges and the lack of available care, Mr. Biziwiki Mwatibu Banda, the clinical officer at Mchinji District Referral Hospital, announced, “We are very thankful to Mudzi Wathu Community Radio for giving youth a platform to express their views and present their complaints… After hearing those complaints, our management decided to train one health care provider from each of the 21 health centers, aiming to provide mental health counseling in all rural areas.”

In the process of spurring these positive changes—and many more like them—the young people involved in this work learned valuable skills that help provide them with more academic and professional opportunities.

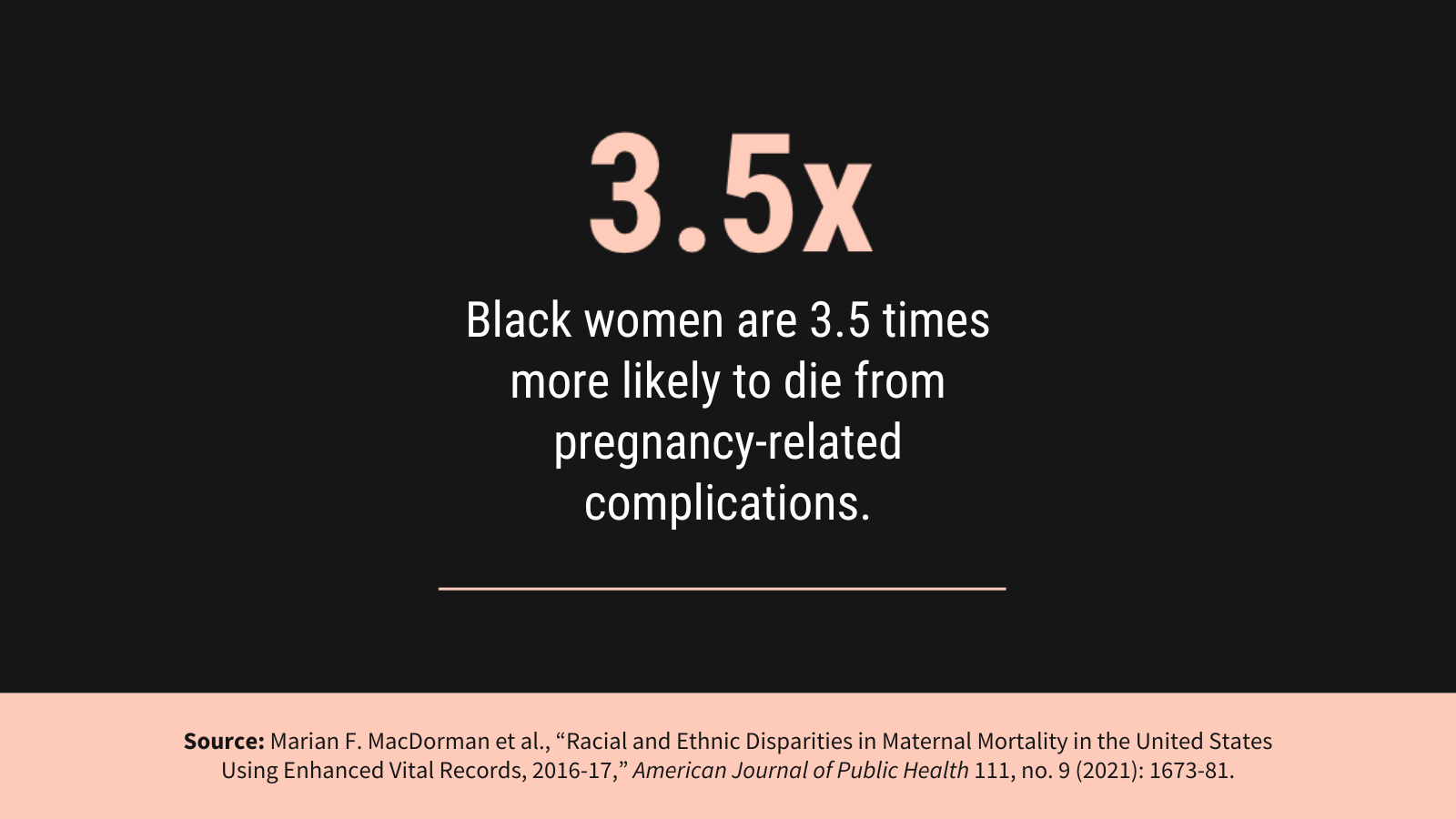

Black women in the United States face a high risk of death from pregnancy-related complications. Most of these deaths are preventable, according to a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “We need new models of care before, during, and after birth to address these inequities,” says Marie Thoma, a reproductive and perinatal epidemiologist and population health scientist at the University of Maryland.

To raise awareness of the Black maternal health crisis in the United States, PRB partnered with creative agency TANK Worldwide and Dr. Shalon’s Maternal Action Project on a 2023 national campaign. It featured data from PRB’s article on NICHD-funded research that found U.S. Black women are 3.5 times more likely to die of pregnancy and postpartum complications than white women. With our partners, we promoted the campaign and research through social media, a press release, and fact sheet, and caught the attention of media, including NPR’s Here and Now. The campaign won a Clio Health award, which recognizes creative marketing and communications in the fields of physical, mental, and social well-being.

Read our follow-up interview with Marie Thoma about emerging research on this crisis.

How can local learning drive global solutions? This question is one we ask daily on the MOMENTUM Knowledge Accelerator project, which is part of USAID’s larger MOMENTUM program that seeks to improve the health and well-being of women, children, and families in more than 38 countries. Part of the project’s role is to identify and share best practices that can be applied across the different settings where MOMENTUM works.

In 2023, MOMENTUM Knowledge Accelerator brought together project staff who are working with their country counterparts to adopt and adapt the World Health Organization’s model of care for small and/or sick newborns in Indonesia, Mali, Nepal, and Nigeria. The goal? Develop a set of common questions and tools to learn about the model’s early rollout in different settings. For instance, how acceptable is the model in these settings? How feasible is it to implement the model in the different country contexts and settings? What adaptations are needed to the model based on the health systems’ contexts? The experiences in each country so far show that when health system and community actors are properly engaged, the model is acceptable, appropriate, and feasible in each setting. If governments can continue to provide resources to support the model’s different elements, more newborns can survive and thrive.

Using this information, we are working to share common approaches and address factors like how different aspects of the health system and variations between the public and private sectors affect the model’s implementation. Identifying and sharing such early insights can help shape global learning and strengthen the quality of care that small and sick newborns receive from their local health care providers—changing and improving lives.

This example is just one of the ways that we collaborate and communicate, gathering and assessing knowledge to share insights that people can put into practice.

Resources—and financial burdens—flow from one generation to another. Understanding how it happens is key for governments focused on fostering sustainable development, and data from national transfer accounts (NTA) can provide key insights.

In 2023, PRB and the Regional Consortium for Research on Generational Economy (CREG) hosted a shared space in Senegal to make complicated topics like the value of women’s unpaid labor easy to understand so decisionmakers could assess needs and accountability. The 3rd National Transfer Account–Africa Conference in La Somone-Senegal, held in partnership with CREG, PRB, the United Nations Population Fund, and United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, brought together more than 130 participants from 19 African countries, including parliamentarians and decisionmakers from various ministries.

The Africa NTA Network, drawn by our reputation for facilitating high-level policy dialogue informed by data, chose PRB to moderate three of four plenary conference sessions. Africa Director Aïssata Fall facilitated a session on the importance of unpaid care work and achieving a demographic dividend, which featured key messages developed by PRB policy communication fellows participating in the conference. She also directed two plenary sessions focused on high-level policy dialogue with parliamentarians and decisionmakers from ministries of planning, budget, gender, and social affairs. They came together to discuss challenges related to the demographic dividend and the care economy and the difficulty of translating these complex and often-abstract concepts so they can be considered in practical applications.

We developed a three-part climate blog series in English and French to advance a new approach to investments in climate adaptation that integrate population, gender, health, and the environment. The series lays the foundation of a people-centered framework for building resilience to climate change centered on agency, equity, and the power of local solutions.

And, in a year that closed as the hottest on record, solutions are more urgent than ever, as is knowing how—and which—populations will be most affected by climate change. Population characteristics like age, gender, and socioeconomic status are a few of the factors that make some people more vulnerable to the effects of a changing climate. Understanding them can help countries adapt and build resilience to future climate-related events, and we put a spotlight on this topic in our 2023 World Population Data Sheet.

We also worked with researchers participating in the 2023 ARUA Climate Change and Inequalities Symposium at the University of Cape Town to provide feedback and coaching on their presentations, which were focused on social inequalities and climate change action, so they could deliver clear, compelling messages. Read our top five tips to make your presentation message stand out.

The year 2023 marked the official end of the COVID-19 state of emergency. Yet the disease continued to spread, and many people continued to feel its effects. Decisionmakers need evidence of these impacts so they can effectively plan for their communities.

PRB’s KidsData program released data and findings from the Family Experiences During the COVID-19 Pandemic survey that highlighted ongoing challenges. The survey checked in with parents and caregivers four times to track the pandemic’s evolving impact on families. The results released in 2023 showed persistent challenges for California families despite suggestions that life had returned to normal.

In California, three years after the pandemic’s onset, children still faced significant COVID-related challenges, and their caregivers remained concerned. As safety-net supports began to roll back, nearly half of parents and caregivers statewide (45%) said their household finances were negatively impacted since the start of the pandemic, up from 32% a year prior. And more than half (58%) said they worried for the safety of their children as public health measures, like masking mandates, relaxed. Rates of concern were even higher in households with children with special health care needs.

The pandemic’s effects on young people are of particular concern as adverse childhood experiences, especially in early childhood, can have negative, long-term impacts on health and well-being. KidsData remains committed to tracking and analyzing data on the health and well-being of California’s children.

How can gender-transformative approaches and programming help improve outcomes for family planning and reproductive health? How can we address the gender inequities that global health workers experience? What are the links between sexual and reproductive health and technology-facilitated gender-based violence? What intersectional approaches are being applied to gender-transformative programming? How can comprehensive sexuality education help strengthen gender-based violence prevention and response efforts and vice versa?

If you are among the more than 2,600 members of the Interagency Gender Working Group (IGWG), you may already know the answers to these questions.

For 13 years, PRB managed the IGWG, a community of practice founded nearly 30 years ago to promote gender-sensitive considerations as a critical factor in improving family planning and reproductive health outcomes and advancing sustainable development.

Under our management, the IGWG highlighted best practices, challenges, and opportunities for promoting gender equality through global health programming, showcased the work of gender experts and advocates around the world, and led discussions on cutting-edge topics on and approaches to gender-transformative health programming.

In late 2023, we transitioned management of the IGWG to the PROPEL Youth and Gender project. During its time with PRB, the IGWG served as a reputable resource for gender experts, advocates, and program implementers working in global health and other sectors. It centered and elevated the voices of gender experts, advocates, and researchers, with special attention to locally led efforts, and the community of practice made notable contributions to the field with products that captured a wealth of knowledge and actionable recommendations for practitioners, advocates, researchers, and donors.

Both seasoned experts and those just beginning to integrate a gender-sensitive lens into their activities rely on materials like the IGWG’s newsletter and signature Gender Integration Continuum, a valuable tool for program implementers that measures whether and how interventions incorporate gender equity to improve development outcomes.

Explore some of our work with the IGWG:

We look forward to watching the IGWG’s continued growth and success.

As part of our activities on the Stawisha Pwani project, we collaborated with county officials, youth, and others in four coastal counties in Kenya as they sought to create and strengthen policies concerning the health of people in their communities.

We worked with officials in Mombasa County’s Department of Health to bring together youth representatives, county officials, and other stakeholders in the private sector and at nongovernmental organizations to develop the Mombasa County Adolescent and Young People Strategy on Health for 2024-2029. In our role of helping to facilitate dialogue, we drafted a template for the strategy and a plan for communicating its benefits to decisionmakers, and then formed a youth technical working group to draft, review, and revise the policy before it was shared with stakeholder groups for their feedback.

This collaborative process resulted in a strategy—approved by the Mombasa County government—that is in use today, helping to guide decisions across County departments on high impact programming for adolescents and young people.

In Taita Taveta County, we helped advance policy change by providing technical assistance to officials reviewing the Health Financing Facility Improvement Fund (FIF) law and developing the FIF operations and supervision manual. The FIF provides a way to collect and manage revenue from the health services delivered by public health facilities, as well as for these facilities to use the revenue to improve service delivery. The County and Subcounty Health Management Teams are relying on the manual as they monitor revenue collection to ensure resources are being used practically and to increase accountability.

The manual’s guidelines and revisions to the FIF law that allow facilities to retain and use revenue—a key element for strengthening health systems in Taita Taveta—contributed to the Department of Health surpassing its FIF collection targets for Fiscal Year 2022-2023. The Taita Taveta County Annual Development Plan 2024/25 reports that the collection goal of KES 100,000,000 was exceeded by more than 50%, for a total of KES 161,118,235. The health facilities can use these additional resources to further improve their efforts to meet the needs of the communities they serve.

![]()

PRB produced articles, blogs, reports, webinars, and other materials in 2023 on a range of topics such as climate adaptation, gender equality, population aging, unpaid care work, and the U.S. labor shortage. Explore some of these works here.

2023 World Population Data Sheet

A New Approach for Climate Resilience

Elements of Climate Resilience: The Foundations of a People-Centered Framework

Five Actions to Help Build Equitable Climate Resilience

Gender Equity for Work and Pay

Eight Demographic Trends We’re Watching as the World Population Passes 8 Billion

PRB CEO Calls for Restoring Public Trust in Data at United Nations Development Event

Comment l’autosoin peut soutenir la résilience en Afrique de l’Ouest et du Centre

How Self-Care Can Support Resilience in West and Central Africa

To Fix the Care Economy, the United States Should Look Internationally

Want Another Perspective on the U.S. Labor Shortage? Talk to a Demographer

The generous support we receive from organizations and individuals helps make our work possible. Thank you.

PRB worked together with 19 organizations in 2023.

Through their generous contributions, the individuals listed here allowed PRB to fund essential program expansion and organizational innovations during the fiscal year ending Sept. 30, 2023.

Informing a Smarter World / Shaping Change for Good

Navigating through Fiscal Year 2022 was an experience in responding to and shaping change: We successfully completed several long-time projects at Population Reference Bureau (PRB), expanded our operations in West Africa, broadened our areas of focus to include self-care and climate adaptation, and began developing a new strategic plan to guide us through the coming years.

Yet for all the change, some things remained constant: Every day, in every PRB office around the world—in Kenya, Senegal, and the United States—our staff continued to work intentionally to bolster people’s and organizations’ capacity to use population data in ways that will advance critical issues like equality, equity, and reproductive health.

For nearly 100 years, PRB has analyzed data, translated research, and shared information widely so it reaches audiences ranging from government officials to researchers, media, advocates, and the public. This work has made a difference in 2022: We developed a new definition of respectful care in reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health. U.S. policymakers are relying on our report about preserving and enhancing the American Community Survey. And our ongoing support to local partners’ research and communication priorities has led to our policy communication training program being embedded in the curricula of five research institutions and universities based in East and West Africa.

This FY22 annual report shares snapshots of some of our activities over the past year, who we worked with, and how our combined efforts came together to make a difference in people’s lives. The voices in this report show that, through all the changes we experience, it’s the relationships we build along the way that allow us to move forward, confident that our actions help ensure good data lead to good decisions that improve lives around the world.

Jeff Jordan, CEO and President

PRB analyzes population data and ensures the research and its applications are understood and used widely by decisionmakers, advocates, and media. Our ability to both assess and easily communicate critical issues about topics like aging, gender equality, and sexual and reproductive health and rights makes us a valued partner and resource for those working at all levels and in all areas of the world, from the United States to Malawi to Bangladesh.

In 2022, we worked with new and long-time partners like the Appalachian Regional Commission, l’Ecole Supérieure de Journalisme des Métiers de l’Internet et de la Communication, Green Girls Platform, the MacArthur Foundation, the U.S. Census Bureau, and the Youth Alliance for Reproductive Health to communicate, convene, and share skills that get evidence-based information into the hands of decisionmakers in government, the private sector, and civil society who can put it to use creating positive change.

![]()

For decades, PRB has worked collaboratively with local organizations and partners so community members lead, set priorities, and identify solutions that are grounded in local realities. The work we do is often out of the spotlight.

The technical assistance and communications support we provide to data users, journalists, policymakers, youth advocates, and others in places like Appalachia, California, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, and Uganda doesn’t make us the center of attention—and that’s how we want it. As our Africa Director, Aïssata Fall, said about our work on the SAFE ENGAGE project, “We [try] to break the mold. It’s not about us having the funding, it’s about the principle and the commitment to partnership.”

From 2017 to 2022, the EEDA project partnered with youth and civil society leaders working on family planning and sexual and reproductive health and rights in Africa and Asia. Together with these partners, EEDA developed tailored, data-driven advocacy strategies and communications materials to increase policy knowledge, strengthen commitment to implementation, increase funding for existing policies, and reinforce systems for promoting accountability. EEDA’s partners continue to make change happen in their communities.

For seven years, the PACE project worked together with local partners to build champions, bridge sectors, and distill evidence to ensure that family planning, reproductive health, and population issues are recognized as key to sustainable and equitable economic growth and development across Africa and Asia. The project ended in 2022, but its focus on connecting with local institutions and intentional shifting of program leadership to local partners ensures its aims and work continue.

For five years, the SAFE ENGAGE project created spaces for dialogue and collaboration among different stakeholders as they worked together to develop strategic messages aimed at improving access to safe abortion, strengthen the capacity of advocates to achieve policy goals, and work with journalists to improve evidence-based reporting. The project’s approach brought together partners from Anglophone and Francophone countries, creating connections that will endure long after the project’s end in FY22.

In the United States, much of the policymaking around population health resides with states and localities. The decentralized nature of decision-making means that, to be effective, research and policy must focus on the communities they serve. PRB’s U.S. Programs staff provide trainings and resources to local leaders around the country to help them find the data they need on population, housing, and health trends so they can understand and respond to their communities’ needs.

In California, we are a force behind the scenes, working as an intermediary between data producers like the U.S. Census Bureau and the California Department of Education. We do the heavy lifting to make data and trends accessible across more than 1,000 indicators so that county program staff, journalists, advocates, and policymakers can spend their limited time and resources focusing on policy and program change instead of looking for the right data.

The KidsData program promotes the health and well-being of children in California by providing an easy-to-use resource that offers high-quality, wide-ranging, local data to those who work on behalf of children in a way that is accessible to policymakers, service providers, grant seekers, media, parents, and others who influence children’s lives.

![]()

PRB information products in 2022 included blogs, briefs, fact sheets, reports, videos, and websites on topics like children’s well-being, family planning and reproductive health, equity, and the challenge of misinformation in today’s world. We’ve curated a sampling for you to explore.

Family Experiences During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Black Women Over Three Times More Likely to Die in Pregnancy, Postpartum Than White Women

Building Up Communities by Breaking Down Data

Dying Young in the United States

Rising Obesity in an Aging America: Policy and Program Implications

The Democratic Republic of the Congo Leads the Way on Abortion Access

The Future of Family Planning in Africa

Resilient Future: Climate Financing Strategies for Family Planning Programs

Youth Family Planning Policy Scorecard

2022 World Population Data Sheet

Data and Demagoguery: Human Rights and Development in the Disinformation Age

We appreciate the organizations and individuals whose generous support makes our work possible. Thank you.

PRB worked together with 48 organizations in 2022.

Through their generous contributions, the individuals listed here allowed PRB to fund essential program expansion and organizational innovations during the fiscal year ending Sept. 30, 2022.